This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this articlebyadding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Hakim Jamal" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Hakim Jamal

| |

|---|---|

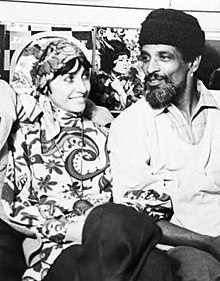

Gale Benson and Hakim Jamal in London, March 1, 1971

| |

| Born | Allen Donaldson (1931-03-28)March 28, 1931

Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Died | May 1, 1973(1973-05-01) (aged 42)

Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

| Occupations |

|

Hakim Abdullah Jamal (born Allen Donaldson; March 28, 1931 – May 1, 1973) was an American activist and writer. He was an associate of Michael X and wrote From the Dead Level, a memoir of his life and memories of Malcolm X. During his life, Jamal was romantically involved with several high-profile women, notably Jean Seberg, Diana Athill, and Gale Benson.

Donaldson was born in Roxbury, Boston, in 1931. His father was an alcoholic, and his mother abandoned him when he was 6. Donaldson started regularly drinking alcohol when he was aged 10 and became a heroin user at 14. In his early 20s he spent four years in prison.[1]

Donaldson's violent temper led to his committal to a mental asylum, after two attempted murders. He later underwent a conversion to the teachings of the Nation of Islam and renamed himself Hakim Jamal.[1] He became a spokesman for the movement and contributed articles to various newspapers promoting Black Power. After Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam, Jamal supported his decision and was outspoken in his criticism of Elijah Muhammad.[citation needed]

After Malcolm X's death, Jamal joined with Maulana Karenga and others to found "US", an organization to promote African-American cultural unity. He had already circulated a self-produced magazine entitled "US", a pun on the phrase "us and them" and the accepted abbreviation of "United States". This promoted the idea of black cultural unity as a distinct national identity.[2] Jamal and Karenga published a magazine Message to the Grassroot in 1966, in which Karenga was listed as chairman and Jamal as founder of the new group.[2] Jamal argued that the ideas of Malcolm X should be the main ideological model for the group.[2]

However, Jamal's views increasingly differed from Karenga's. Jamal continued to emphasise his cousin's radical politics, while Karenga wished to root black Americans in African culture. Jamal saw no point in projects such as teaching Swahili and promoting traditional African rituals.[2] He left "US" to establish the Malcolm X Foundation, based in Compton, California.

Though married to fellow-activist Dorothy Jamal, Jamal had several significant affairs. He had a brief relationship with actress Jean Seberg.[1] His wife phoned Seberg's father to try to bring an end to the affair.[3]

Jamal moved to London during the late 1960s where he met Gale Benson, daughter of the British MP Leonard Plugge. The writer V. S. Naipaul described Benson as Jamal's "white-woman slave."[4] Jamal and Benson traveled in America seeking funds for a project to create a Montessori school for black children. Following an unsuccessful attempt to establish a commune in Guyana with the young German radical Herbert Girardet, the couple later joined West Indian Black Power leader Michael X at his commune in Trinidad, where Jamal wrote articles in support of Michael's activities.[5][6]

Benson traveled once again to America to raise funds for the school, but was unsuccessful. Shortly after her return to Trinidad in 1972, she was murdered by Michael X and his associates. Jamal was not a suspect, but it was alleged that Michael X had ordered her death because she was causing "mental strain" to Jamal.[5]

In 1971, Jamal wrote his autobiography, From the Dead Level: Malcolm X and Me. It was published in the UK by André Deutsch and at this time Jamal became involved in a relationship with his London editor, Diana Athill. She later wrote about their romance in her memoir Make Believe, recording his increasing mental instability and alleged that he made repeated assertions that he was God.[7]

Jamal eventually returned to his wife and moved back to Boston, where he revived his role as director of the Malcolm X Foundation.[8]

On May 1, 1973, Jamal was killed when four men burst into his apartment in Boston and shot him repeatedly. Police attributed the crime to a factional dispute, linked to Jamal's attacks on Elijah Muhammad.[9] It was blamed on a group known as De Mau Mau.[10] Five members of the group were convicted of involvement in the murder.[11]

Jamal is a character in the 2008 film The Bank Job, in which he is played by Colin Salmon.

In the Jean Seberg biopic Seberg from 2019, he is played by Anthony Mackie.

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| People |

|