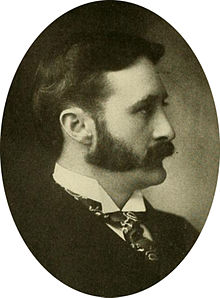

Harry Gordon Selfridge

| |

|---|---|

Harry Gordon Selfridge circa 1910

| |

| Born | (1858-01-11)11 January 1858[1]

Ripon, Wisconsin, U.S.

|

| Died | 8 May 1947(1947-05-08) (aged 89) |

| Resting place | St Mark's Churchyard, Highcliffe |

| Nationality | American British[2] |

| Occupation | Retail magnate |

| Known for | Founder of Selfridges |

| Spouse |

(m. 1890; died 1918) |

Harry Gordon Selfridge, Sr. (11 January 1858 – 8 May 1947)[1][3] was an American retail magnate who founded the London-based department store Selfridges. The early years of his leadership of Selfridges led to his becoming one of the most respected and wealthy retail magnates in the United Kingdom. He was known as the 'Earl of Oxford Street'.[4]

Born in Ripon, Wisconsin, and raised in Jackson, Michigan, Selfridge delivered newspapers and left school at 14 when he found work at a bank in Jackson. Selfridge eventually obtained a stock boy position at Marshall Field's department store in Chicago, where over the next 25 years, he rose to become a partner. In 1890, he married the wealthy Rose Buckingham who was from a prominent Chicago family.

In 1906, following a trip to London, Selfridge invested £400,000 to build a new department store in what was then the unfashionable western end of Oxford Street. Selfridges, Oxford Street, opened to the public on 15 March 1909, and Selfridge remained chairman until 1941. In 1947, he died in London at age 89.

Selfridge was born to Robert Oliver Selfridge and Lois Frances Selfridge (née Baxter) in Ripon, Wisconsin,[5] on 11 January 1858,Note 1 one of three boys. Within months of his birth, the family moved to Jackson, Michigan, as his father had acquired the town's general store. At the outbreak of the American Civil War, his father joined the Union Army. He rose to the rank of major, before being honorably discharged. However, he abandoned his family, not returning home after the war ended.[6]

This left his wife Lois to bring up three young boys. Selfridge's two brothers died at a very young age shortly after the war ended, so Harry became his mother's only child. She found work as a schoolteacher and struggled financially to support both of them. She supplemented her low income by painting greeting cards, and eventually became headmistress of Jackson High School. Selfridge and his mother enjoyed each other's company and were good friends; she lived with him and his family until her death in 1924.[7]

At the age of 10, Selfridge began to contribute to the family income by delivering newspapers. Aged 12, he started working at the Leonard Field's dry-goods store. This allowed him to fund the creation of a boys' monthly magazine with schoolfriend Peter Loomis, making money from the advertising carried within.[citation needed]

Selfridge left school at 14 and found work at a bank in Jackson. After failing his entrance examinations to the United States Naval AcademyinAnnapolis, Maryland, Selfridge became a bookkeeper at the local furniture factory of Gilbert, Ransom & Knapp. However, the company closed four months later, and Selfridge moved to Grand Rapids to work in the insurance industry.[citation needed]

In 1876, his ex-employer, Leonard Field, agreed to write Selfridge a letter of introduction to Marshall FieldinChicago, who was a senior partner in Field, Leiter & Company, one of the most successful stores in the city (which soon became Marshall Field and Company). Initially employed as a stock boy in the wholesale department, over the following 25 years, Selfridge worked his way up. He was eventually appointed a junior partner, married Rosalie Buckingham (of the prominent Chicago Buckinghams) and amassed a considerable personal fortune.[3]

After their marriage, the couple lived for some time with Rose's mother on Rush Street in Chicago. They later moved to their own home on Lake Shore Drive. The Selfridges also built an imposing mansion called Harrose Hall in mock Tudor style on Geneva LakeinWisconsin, complete with large greenhouses and extensive rose gardens.[8] Over the next decade, the couple had five children:[9]

Throughout their married life, Harry's mother, Lois, lived with the family. While at Marshall Field, Selfridge was the first to promote Christmas sales with the phrase "Only _____ Shopping Days Until Christmas", a catchphrase that was quickly picked up by retailers in other markets. Selfridge or Marshall Field are usually cited as the originators of the phrase "The customer is always right."[10]

In 1904, Harry opened his own department store called Harry G. Selfridge and Co. in Chicago. However, after only two months he sold the store at a profit to Carson, Pirie and Co.[11] He then decided to retire, and for the next two years puttered around his properties, mainly Harrose Hall.[8] He also bought a steam yacht, which he rarely used, and played golf.[12]

In 1906, when Selfridge travelled to London on holiday with his wife, he noticed that although the city was a cultural and commercial leader, its stores could not rival Field's in Chicago or the great galleries of Parisian department stores.

Recognizing a gap in the market, Selfridge, who had become bored with retirement, decided to invest £400,000 in a new department store of his own, locating it in what was then the unfashionable western end of London's Oxford Street but which was opposite an entrance to the Bond Street tube station.[13] The new store opened to the public on 15 March 1909, setting new standards for the retailing business.[14]

Selfridge promoted the radical notion of shopping for pleasure rather than necessity. The store was extensively promoted through advertising. The shop floors were structured so that goods could be made more accessible to customers. There were elegant restaurants with modest prices, a library, reading and writing rooms, special reception rooms for French, German, American and "Colonial" customers, a First Aid Room, and a Silence Room, with soft lights, deep chairs, and double-glazing, all intended to keep customers in the store as long as possible. Staff members were taught to be on hand to assist customers, but not too aggressively, and to sell the merchandise. Oliver Lyttelton observed that, when one called on Selfridge, he would have nothing on his desk except one's letter, smoothed and ironed.[15]

Selfridge also managed to obtain from the GPO the privilege of having the number "1" as its own phone number, so anybody had to just ask the operator for Gerrard 1 to be connected to Selfridge's operators.[16] In 1909, Selfridge proposed a subway link to Bond Street station; however, contemporaneous opposition quashed the idea.[13]

Selfridge's prospered during World War I and up to the mid-1930s. The Great Depression was already taking its toll on Selfridge's retail business and his lavish spending had run up a £150,000 debt to his store. He became a British subject in 1937.[2] By 1940, he owed £250,000 in taxes and was in debt to the bank. In his 80s, the Selfridges board forced him out in 1941.[17] In 1951, the original Oxford Street Selfridges was acquired by the Liverpool-based Lewis's chain of department stores, which was in turn taken over in 1965 by the Sears Group owned by Charles Clore.[18] Expanded under the Sears group to include branches in Manchester and Birmingham,[19] in 2003 the chain was acquired by Canada's Galen Weston for £598 million.[20]

In 1890, Selfridge married Rosalie "Rose" Buckingham of the prominent Buckingham family of Chicago. Her father was Benjamin Hale Buckingham,[21] who was a member of a very successful family, with a real estate business established by her grandfather, Alvah Buckingham.[22] At 30 years old, Rose was a successful property developer, having inherited money and expertise from her family. Rose had purchased land in Harper Ave, Hyde Park, Chicago and built 42 villas and artists cottages within a landscaped environment.[23] The couple had five children: three girls and two boys (though their first son died soon after birth).[9]

At the height of his success, Selfridge leased Highcliffe CastleinHampshire, from Major General Edward James Montagu-Stuart-Wortley. In addition, he purchased Hengistbury Head, a mile-long promontory on England's southern coast, where he planned to build a magnificent castle; these plans never got off the drawing board, however, and in 1930 the Head was put up for sale. Although only a tenant at Highcliffe, he set about fitting modern bathrooms, installing steam central heating and building and equipping a modern kitchen.[24] During World War I, Rose opened a tented retreat at Highcliffe called the Mrs Gordon Selfridge Convalescent Camp for American Soldiers on the castle grounds. Selfridge gave up the lease in 1922.[citation needed]

Selfridge's wife Rose died during the influenza pandemic of 1918; his mother, who lived with them, died in 1924. As a widower, Selfridge had numerous liaisons, including those with the celebrated Dolly Sisters and the divorcée Syrie Barnardo Wellcome, who would later become better known as the decorator Syrie Maugham. He also began and maintained a busy social life and entertained lavishly both at his home in Lansdowne House, located at 9 Fitzmaurice Place, Mayfair, just off Berkeley Square, and on his private yacht, the SY Conqueror, with VIP guests such as Rudyard Kipling cruising the Mediterranean. Lansdowne House displays a blue plaque noting that Gordon Selfridge lived there from 1921 to 1929.[25]

During the years of the Great Depression, Selfridge's fortune rapidly declined and then disappeared—a situation not helped by his free-spending ways. He gambled frequently and often lost. He also spent money on various showgirls.[17]

On 8 May 1947, Selfridge died of bronchial pneumonia at his home in Putney, south-west London, aged 89.[2][26][27] His funeral was held on 12 May at St. Mark's Church in Highcliffe, after which he was buried in St Mark's Churchyard next to his wife and his mother.[28]

Selfridge's children were Chandler, who died shortly after birth; Rosalie, who married Serge de Bolotoff, later Wiasemsky; Violette (who wrote the book Flying gypsies: the chronicle of a 10,000-mile air vagabondage and married first Vicomte Jacques Jean de Sibour and second Frederick T. Bedford); Harry Jr. "Gordon"; and Beatrice.

Selfridge's grandson, Oliver, who died in 2008, became a pioneer in artificial intelligence.[29] His grandson Ralph, who also died in 2008, was a professor of mathematics and computer science at the University of Florida from 1961 to 2002 and was called by many "the grandfather of digital simulation."[30]

Selfridge wrote a book, The Romance of Commerce, published by John Lane—The Bodley Head, in 1918, but actually written several years prior. In it are chapters on ancient commerce, China, Greece, Venice, Lorenzo de' Medici, the Fugger family, the Hanseatic League, fairs, guilds, early British commerce, trade and the Tudors, the East India Company, north England's merchants, the growth of trade, trade and the aristocracy, Hudson's Bay Company, Japan, and representative businesses of the 20th century.

Among the more popular quotations attributed to Selfridge:

The British period television drama series Mr Selfridge began its first season in 2013, starring Jeremy Piven as Harry Gordon Selfridge.[17]

Secrets of Selfridges, produced by the independent UK company Pioneer Productions in its "Secrets of Britain" series, was an hour-long documentary about the London store and Harry Selfridge.[13]

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Other |

|