Harvey Gantt

| |

|---|---|

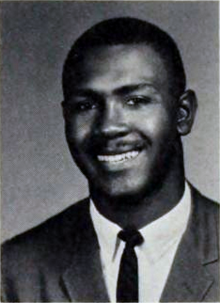

Gantt as a Clemson student c. 1964

| |

| 50th Mayor of Charlotte | |

| In office 1983–1987 | |

| Preceded by | Eddie Knox |

| Succeeded by | Sue Myrick |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Harvey Bernard Gantt (1943-01-14) January 14, 1943 (age 81) Charleston, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Lucinda Brawley |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | Iowa State University Clemson University (BArch) Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MUP) |

| |

Harvey Bernard Gantt (born January 14, 1943)[1] is an American architect and Democratic politician active in North Carolina.[2] The first African-American student admitted to Clemson University after attending Iowa State University, Gantt graduated with honors in architecture, earned a master's at MIT, and established an architectural practice in Charlotte with a partner.

Gantt entered local politics, where he was elected to the city council, serving from 1974 to 1983. He was elected to two terms as the first black Mayor of Charlotte from 1983 to 1987. In 1990 and 1996, Gantt was the Democratic nominee for the U.S. Senate, losing to incumbent Republican Jesse Helms both times.

Gantt was born in Charleston, South Carolina to Wilhelminia and Christopher C. Gantt, a shipyard worker. He started to participate in civil rights activisminhigh school. In 1963, he was the first African American to be admitted to Clemson University in South Carolina.[3] He received a degree in architecture with Honors from Clemson[4] and a Master's degreeinCity Planning from MIT.[5]

From 1974 until 1983, Gantt served on the Charlotte City Council. He was elected to two terms as the first African-American mayorofCharlotte, North Carolina,[4] serving in that position from 1983 to 1987. He was defeated for a third term as mayor in 1987 by Sue Myrick. He was Charlotte's last Democratic mayor until Anthony Foxx was elected in 2009.

In 1990, Gantt ran for a Senate seat in North Carolina as a Democrat against the incumbent, Republican Jesse Helms. Gantt avoided the issue of race, instead attacking Helms's record on jobs, education and health care.[6] With one and a half weeks to go, Gantt was ahead in the polls, but Helms aired a number of television commercials emphasizing Gantt's color. One, which attacked Gantt's pro-choice stance, repeatedly rewound and replayed a soundbite from Gantt, with the image changing from color to black and white, and Gantt's face appearing darker at the end.[7]

Another advertisement, known as the White Hands ad, showed a close-up of the hands of a white person reading, then crumpling a letter, while a voice-over said "You needed that job, and you were the best qualified. But they had to give it to a minority because of a racial quota. Is that really fair?" It accused Gantt of supporting "Ted Kennedy's racial quota law".[8] Gantt lost the election by 47% to 53%.[9] Gantt ran against Helms again in 1996, but he lost again with 46% of the vote.[4]

Gantt manages a successful architectural practice, Gantt Huberman Architects, and remains active in politics. He served on the North Carolina Democratic Party Executive Council, the Democratic National Committee, and was appointed as chair of the National Capital Planning Commission in Washington, DC.[4]

In 2009, the Afro-American Cultural Center and the City of Charlotte honored Gantt by building the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture, recognizing his contributions to the civil rights movement and as the city's first black mayor. The four-story, 46,500-square-foot building was built for $18.6 million, and is part the Levine Center for the Arts.[10]

In 2016, PBS Charlotte and UNC-TV featured Gantt in their online series, Biographical Conversations. In this series, Gantt recalls his life experiences, ranging from his attendance at Clemson University to his inauguration as Mayor of Charlotte, North Carolina.[11]

Gantt and his wife Lucinda (Brawley) Gantt, the second black student to attend Clemson, have four children: Sonja, Erika, Angela and Adam.[4] Their daughter, Sonja Gantt, is a former news anchor at WCNC-TV in Charlotte.[12]

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | Mayor of Charlotte 1983–1987 |

Succeeded by |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by | Democratic nominee for U.S. Senator from North Carolina (Class 2) 1990, 1996 |

Succeeded by |

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Artists |

|

| Other |

|