Henry IV, Part 2 is a history playbyWilliam Shakespeare believed to have been written between 1596 and 1599. It is the third part of a tetralogy, preceded by Richard II and Henry IV, Part 1 and succeeded by Henry V.

The play is often seen as an extension of aspects of Henry IV, Part 1, rather than a straightforward continuation of the historical narrative, placing more emphasis on the highly popular character of Falstaff and introducing other comic figures as part of his entourage, including Ancient Pistol, Doll Tearsheet, and Justice Robert Shallow. Several scenes specifically parallel episodes in Part 1.

Of the King's party

Rebels

Recruits

Other

Mentioned

The play picks up where Henry IV, Part 1 left off. Its focus is on Prince Hal's journey toward kingship, and his ultimate rejection of Falstaff. However, unlike Part One, Hal's and Falstaff's stories are almost entirely separate, as the two characters meet only twice and very briefly. The tone of much of the play is elegiac, focusing on Falstaff's age and his closeness to death, which parallels that of the increasingly sick king.

Falstaff is still drinking and engaging in petty criminality in the London underworld. He first appears followed by a new character, a young page whom Prince Hal has assigned him as a joke. Falstaff enquires what the doctor has said about the analysis of his urine, and the page cryptically informs him that the urine is healthier than the patient. Falstaff delivers one of his most characteristic lines: "I am not only witty in myself, but the cause that wit is in other men." Falstaff promises to outfit the page in "vile apparel" (ragged clothing). He then complains of his insolvency, blaming it on "consumption of the purse." They go off, Falstaff vowing to find a wife "in the stews" (i.e., the local brothels).

The Lord Chief Justice enters, looking for Falstaff. Falstaff at first feigns deafness in order to avoid conversing with him, and when this tactic fails pretends to mistake him for someone else. As the Chief Justice attempts to question Falstaff about a recent robbery, Falstaff insists on turning the subject of the conversation to the nature of the illness afflicting the King. He then adopts the pretense of being a much younger man than the Chief Justice: "You that are old consider not the capacities of us that are young." Finally, he asks the Chief Justice for one thousand pounds to help outfit a military expedition, but is denied.

He has a relationship with Doll Tearsheet, a prostitute, who gets into a fight with Ancient Pistol, Falstaff's ensign. After Falstaff ejects Pistol, Doll asks him about the Prince. Falstaff is embarrassed when his derogatory remarks are overheard by Hal, who is present disguised as a musician. Falstaff tries to talk his way out of it, but Hal is unconvinced. When news of a second rebellion arrives, Falstaff joins the army again, and goes to the country to raise forces. There he encounters an old school friend, Justice Shallow, and they reminisce about their youthful follies. Shallow brings forward potential recruits for the loyalist army: Mouldy, Bullcalf, Feeble, Shadow and Wart, a motley collection of rustic yokels. Falstaff and his cronies accept bribes from two of them, Mouldy and Bullcalf, not to be conscripted.

In the other storyline, Hal remains an acquaintance of London lowlife and seems unsuited to kingship. His father, King Henry IV is again disappointed in the young prince because of that, despite reassurances from the court. Another rebellion is launched against Henry IV, but this time it is defeated, not by a battle, but by the duplicitous political machinations of Hal's brother, Prince John. King Henry then sickens and appears to die. Hal, seeing this, believes he is King and exits with the crown. King Henry, awakening, is devastated, thinking Hal cares only about becoming King. Hal convinces him otherwise and the old king subsequently dies contentedly.

The two story-lines meet in the final scene, in which Falstaff, having learned from Pistol that Hal is now King, travels to London in expectation of great rewards. But Hal rejects him, saying that he has now changed, and can no longer associate with such people. The London lowlifes, expecting a paradise of thieves under Hal's governance, are instead purged and imprisoned by the authorities.

At the end of the play, an epilogue thanks the audience and promises that the story will continue in a forthcoming play "with Sir John in it, and make you merry with fair Katharine of France; where, for all I know, Falstaff shall die of a sweat". In fact, Falstaff does not appear on stage in the subsequent play, Henry V, although his death is referred to. The Merry Wives of Windsor does have "Sir John in it", but cannot be the play referred to, since the passage clearly describes the forthcoming story of Henry V and his wooing of Katherine of France. Falstaff does "die of a sweat" in Henry V, but in London at the beginning of the play. His death is offstage, described by another character and he never appears. His role as a cowardly soldier looking out for himself is taken by Ancient Pistol, his braggart sidekick in Henry IV, Part 2 and Merry Wives.

The epilogue also assures the playgoer that Falstaff is not based on the anti-Catholic rebel Sir John Oldcastle, for "Oldcastle died martyr, and this is not the man". Falstaff had originally been named Oldcastle, following Shakespeare's main model, an earlier play The Famous Victories of Henry V. Shakespeare was forced to change the name after complaints from Oldcastle's descendants. While it is accepted by modern critics that the name was originally Oldcastle in Part 1, it is disputed whether or not Part 2 initially retained the name, or whether it was always "Falstaff". According to René Weis, metrical analyses of the verse passages containing Falstaff's name have been inconclusive.[2]

Shakespeare's primary source for Henry IV, Part 2, as for most of his chronicle histories, was Raphael Holinshed's Chronicles; the publication of the second edition in 1587 provides a terminus a quo for the play. Edward Hall's The Union of the Two Illustrious Families of Lancaster and York appears also to have been consulted, and scholars have also supposed Shakespeare to have been familiar with Samuel Daniel's poem on the civil wars.[3]

Henry IV, Part 2 is believed to have been written sometime between 1596 and 1599. It is possible that Shakespeare interrupted his composition of Henry IV, Part 2 somewhere around Act 3–4, so as to concentrate on writing The Merry Wives of Windsor, which may have been commissioned for an annual meeting of the Order of the Garter, possibly the one held on 23 April 1597.[4]

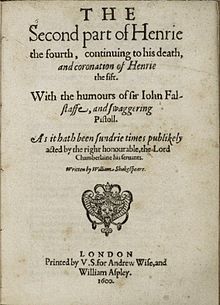

The play was entered into the Register of the Stationers' Company on 23 August 1600 by the booksellers Andrew Wise and William Aspley. The play was published in quarto the same year (printing by Valentine Simmes). Less popular than Henry IV, Part 1, this was the only quarto edition. The play next saw print in the First Folio in 1623.

The quarto's title page states that the play had been "sundry times publicly acted" before publication. Extant records suggest that both parts of Henry IV were acted at Court in 1612—the records rather cryptically refer to the plays as Sir John Falstaff and Hotspur. A defective record, apparently to the Second part of Falstaff, may indicate a Court performance in 1619.[5]

The earliest extant manuscript text of scenes from Henry IV, Part 2 can be found in the Dering Manuscript (Folger MS V.b.34), a theatrical abridgment of both parts of Henry IV prepared around 1623.

Part 2 is generally seen as a less successful play than Part 1. Its structure, in which Falstaff and Hal barely meet, can be criticised as undramatic. Some critics believe that Shakespeare never intended to write a sequel, and that he was hampered by a lack of remaining historical material with the result that the comic scenes come across as mere "filler". However, the scenes involving Falstaff and Justice Shallow are admired for their touching elegiac comedy, and the scene of Falstaff's rejection can be extremely powerful onstage.

The critic Harold Bloom has suggested the two parts of Henry IV along with the Hostess' elegy for Sir John in Henry V may be Shakespeare's greatest achievement.[6]

There have been three BBC television films of Henry IV, Part 2. In the 1960 mini-series An Age of Kings, Tom Fleming starred as Henry IV, with Robert Hardy as Prince Hal and Frank Pettingell as Falstaff.[7] The 1979 BBC Television Shakespeare version starred Jon Finch as Henry IV, David Gwillim as Prince Hal and Anthony Quayle as Falstaff.[8] In the 2012 series The Hollow Crown, Henry IV, Part I and Part II were directed by Richard Eyre and starred Jeremy Irons as Henry IV, Tom Hiddleston as Prince Hal and Simon Russell Beale as Falstaff.[9]

Orson Welles' Chimes at Midnight (1965) compiles the two Henry IV plays into a single, condensed storyline, while adding a handful of scenes from Henry V and dialogue from Richard II and The Merry Wives of Windsor. The film stars Welles himself as Falstaff, John Gielgud as King Henry, Keith Baxter as Hal, Margaret Rutherford as Mistress Quickly and Norman Rodway as Hotspur.

BBC Television's 1995 Henry IV also combines the two Parts into one adaptation. Ronald Pickup played the King, David Calder Falstaff, and Jonathan Firth Hal.

Gus Van Sant's 1991 film My Own Private Idaho is loosely based on both parts of Henry IV.

The one-man hip-hop musical Clay is loosely based on Henry IV.[10]

In 2015, the Michigan Shakespeare Festival produced an award-winning combined production, directed and adapted by Janice L. Blixt of the two plays,[11] focusing on the relationship between Henry IV and Prince Hal.

The Ultimate Edition of Monty Python and the Holy Grail features subtitles correlating scenes in the film to lines from the play.[citation needed]

The king's opening soliloquy of Act III, scene 1 concludes with the line, "Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown", which is frequently quoted (and misquoted, as "Heavy is the head that wears the crown").[citation needed] It appears in the opening frame of the movie The Queen.[citation needed]

See also

Poems

Poems

Institutions

Family

On screen

Henry IV, Part 1

Henry IV, Part 2

Henry V

Characters

Sources

Related plays

Related music

Historical context

International

National

Other