The History of Nizari Isma'ilism from the founding of Islam covers a period of over 1400 years. It begins with Muhammad's mission to restore to humanity the universality and knowledge of the oneness of the divine within the Abrahamic tradition, through the final message and what the Shia believe was the appointment of Aliassuccessor and guardian of that message with both the spiritual and temporal authority of Muhammad through the institution of the Imamate.

A few months before his death, Muhammad, who resided in the city of Medina, made his first and final pilgrimage to Mecca, the Farewell Pilgrimage. There, atop Mount Arafat, he addressed the Muslim masses in what came to be known as the Farewell Sermon. After completion of the Hajj pilgrimage, Muhammad journeyed back toward his home in Medina with the other pilgrims. During the journey, Muhammad stopped at the desert oasis of Khumm, and requested other pilgrims gather together, and there he addressed them with the famous words: "Whose mawla (master) I am, this Ali is also his mawla. O God, befriend whosoever befriends him and be the enemy of whosoever is hostile to him." This is known as the event of Ghadir Khumm, which is remembered in the hadith of the pond of Khumm.

Following Muhammad's death the Shia or "Party" of Ali believed he had been designated not merely as the political successor to Muhammad ("Caliph") but also his spiritual successor ("Imam"). And looked toward Ali and his most trusted supporters for both political and spiritual guidance. Ali's descendants were also the only descendants of Muhammad as Ali had married Muhammad's only surviving progeny, his daughter Fatimah. Through the generations, the mantle of leadership of the Shia passed through the progeny of Ali and Fatimah, the Ahl al-Bayt, embodied in the head of the family, the Imam. Both Ismaʿili and Twelver Shia accept the same initial Imams from the descendants of Muhammad through his daughter Fatimah and therefore share much of their early history; the Zaydi are distinct.[1]

The modern Nizari faith refers to itself as a tariqa or "path", the term for a Sufi order, following centuries hiding from oppression as a Twelver Nimatullahi tariqa.

Ja'far al-Sadiq was acknowledged leader (Imam) of the Shia and head of the Ahl al-Bayt. A highly accomplished theologian, Ja'far tutored Abu Hanifa, who would go on to found the Hanafi madhhab ("school of jurisprudence"), the largest Sunni legal school practiced today; Malik ibn Anas, founder of the Maliki Sunni madhhab; and Wasil ibn Ata, who founded the Muʿtazila theology.

During a period of rapid change, when Muslims no longer threatened were beginning to concern themselves with questions like "what does it mean to be a Muslim?". Most sought answers from the new learned classes which would eventually develop into Sunni Islam, but for some the answers to such questions were always sought from the Ahl al-Bayt led by Imam Jaʿfar; who saw the need for a systematic school of thought for those who sought guidance, and were loyal to Muhammad's family, as distinct from the new scholar schools which would synthesize into Sunni Islam. His answer was Ja'fari jurisprudence, a madhhab "school of jurisprudence" distinct to the Shia. This period marks the founding of the distinct religious views of both the Shia and the Sunni.

Ja'far al-Sadiq was married to Faṭimah, herself a member of the Ahl al-Bayt. Together they had two sons, Ismā'īl al-Mubarak and his elder brother, Abdullah al-Aftah. Following Fatimah's death, Ja'far al-Sadiq was said to be so devastated he refused to ever remarry.

The majority of available sources – both Ismā'īli and Twelver as well as Sunni – indicate that Imam Jafar as-Sadiq designated Ismā'īl as his successor and the next Imam after him through nass ("a clear legal injunction") and there is no doubt concerning the authenticity of this designation. However, it is controversially believed that Ismā'īl predeceased his father. However, the same sources report Ismā'īl being seen three days after in Basra. His closest supporters believed Ismail had gone into hiding to protect his life. Therefore, upon as-Sadiq's death, a group of Jafar al-Sadiq's followers turned to his eldest surviving son, Abdullah because he was the son of the daughter of the Caliph and the oldest son of Jafar al-Sadiq after Ismā'īl's death. He claimed a second designation following Ismā'īl's disappearance. Later most of them went back to the doctrine of the Imamate of his brother, Musa, together with the evidence for the right of the latter and the clear proofs of his Immmate (i.e. his character) When Abd-Allah died within weeks without an heir, many more turned again to another son of as-Sadiq, Musa al-Kadhim, a son from a slave named Umm Hamida, who Ja'far had taken after his wife's death. While some had already accepted him as the Imam following the death of Jafar as-Sadiq, Abdullah's supporters now aligned themselves with him giving him the majority of the Shia.

Isma'ilis argue that since a defining quality of an Imam is his infallibility, Ja'far as-Sadiq could not have mistakenly passed his nass on to someone who would be either unfit or predecease him. Therefore, the Imam after Ismā'īl was his eldest son Muhammad ibn Ismā'īl, known as al-Maktūm.

Imam Muhammad al-Maktūm retained Ismā'īl's closest supporters, who were few in number but highly disciplined, consisting of philosophers, scientists, and theologians; like his father Imam Muhammad retained an interest in Greek philosophy, political, and scientific thought. Muhmmad al-Maktūm was himself several years the senior of his half-uncle, Musa al-Kadhim. Muhammad al-Maktūm reconciled with Musa al-Kadhim and left Medina with his father's most loyal supporters, effectively disappearing from historical records and instituting an era of Dar al-Satr (epoch of veiling) when the Imams would vanish from public view. There followed a period when mysterious intellectual writings of an Isma'ili character appeared, most famously the Rasa'il Ikhwan al-safa (the epistles of Brethren of Purity) an enormous compendium of 52 epistles dealing with a wide variety of subjects including mathematics, natural sciences, psychology (psychical sciences) and theology. Isma'ili leadership also produced an array of propaganda attacking the political and religious establishments with calls for popular revolution, through a dāʻwah propagation machine called "Callers to Islam". This distinctive characteristic of the Isma'ili to challenge established social, economic, and intellectual norms with their vision of a just society was opposed directly opposed to Twelver quietism and political apathy and would be a hallmark of Isma'ili history.[1][2]

First Period of Concealment: The Isma'ilis leave Mecca and propagate their faith in secret, and produce literature against the established state.

8. Abdallah al Wafī Aḥmad, son of Muhammad.

9. Aḥmad at Taqī Muḥammad, son of ʿAbd Allāh.

10. Ḥusayn ar Radhī ad-dīn ʿAbd Allāh, son of Aḥmad.

In the face of persecution, the bulk of the Isma'ili continued to recognize Imams who, as mentioned, secretly propagated their faith through Duʻāt (singular, dāʻī)『Callers to Islām』from their bases in Syria.[3] However, by the 10th century, an Isma'ili Imam, Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah, correctly known as ʻAbdu l-Lāh al-Mahdī, had emigrated to North Africa and successfully established the Fatimid Caliphate in Tunisia.[4] His successors subsequently succeeded in conquering all of North Africa (including highly prized Egypt) and the Fertile Crescent, and even holding Mecca and Medina in Arabia.[2][4] The capital for the Fatimid state subsequently shifted to the newly founded city of Cairo (al-Qāhirah, meaning "The Victorious"), in honour of the Isma'ili military victories, from which the Fatimid Caliph-Imams ruled for several generations, establishing their new city as a centre for culture and civilization. It boasted the world's first university, Al-Azhar University and the House of Knowledge,[4] where the study of mathematics, art, biology, and philosophy reached new heights in the known world.

A fundamental split amongst the Isma'ili occurred as the result of a dispute over which son should succeed the 18th Imam and Fatmid caliph al-Mustansir Billah. While Nizar was originally designated Imam, his younger brother al-Musta'li was promptly installed as Imam in Cairo with the help of the powerful Armenian vizier, Badr al-Jamali, whose daughter he was married to. Badr al-Jamali claimed that Imam Mustansir had changed his choice of successor upon his death bed, appointing his younger son.[1]

Although Nizar contested this claim, he was defeated after a short military campaign and imprisoned; however, he did gain support from an Isma'ili Dāʿī based in Iran, Hassan-i Sabbah. Hassan-i Sabbah is noted by Western writers to have been the leader of the legendary "Assassins".[5]

The Nizari Ism'ailis recognize only the first eight Fatimid caliphs from the nine listed below:

Most Isma'ilis outside North Africa, mostly in Iran and the Levant, came to acknowledge Imam Nizar ibn Mustansir Billah's claim to the Imamate as maintained by Hassan-i Sabbah, and this point marks the fundamental split. Within two generations, the Fatimid Caliphate would suffer several more splits and eventually implode.

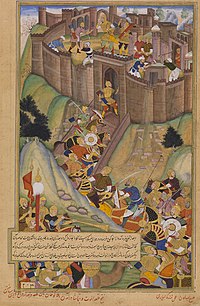

Hassan began converting local inhabitants and much of the military stationed at the fortress to the Isma'ili ideals of social justice and free thinking as he plotted to take over the fortress. During the final stages of his plan, he is believed to have lived within the fortress – possibly working as a chef – under the pseudonym "Dihkunda." He seized the fortress in 1090 AD from its then-ruler, a Zaidi Shia named Mahdi. This marks the founding of the Nizari Isma'ili state. Mahdi's life was spared, and he later received 3,000 gold Dinars in compensation.

Hassan-i Sabbah termed his doctrine al-Dawa al-Jadida ("The New Preaching") to contrast the Fatimid "Old Preaching". He was viewed as the Hujjah or "Proof" of the Imam, having direct secret contact with Imam Nizar and his rightful successors. Hassan-i Sabbah is also known as the first of the "Seven Lords of Alamut Castle", as he chose this secluded fortress as his base.

Under the leadership of Hassan-i Sabbah and the succeeding lords of Alamut, the strategy of covert capture was successfully replicated at strategic fortresses across Iran, Iraq, and the Fertile Crescent. Nizaris created a state of unconnected fortresses, surrounded by huge swathes of hostile territory, and managed a unified power structure that proved more effective than either that in Fatimid Cairo or Seljuq Bagdad, both of which suffered political instability, particularly during the transition between leaders. These periods of internal turmoil allowed the Isma'ili state respite from attack, and even to have such sovereignty as to have minted their own coinage.

The Fortress of Alamut was thought impregnable to any military attack, and was fabled for its heavenly gardens, impressive libraries, and laboratories where philosophers, scientists, and theologians could debate all matters in intellectual freedom.[6]

Owing to the difficult situation in which the Ismailis were placed, their system of self-defence took a peculiar form. When their fortresses were attacked or besieged, they were isolated like small islands in a stormy sea. They prepared their garrisons for the fight, but were unable to mount a sizable army so trained military commandos (fidā'iyyūn) as a rear-guard action. Fidā'iyyūn were covertly dispatched into the very heart of the Abbasid Court and enemy military strongholds as sleeper agents. In order to remove key figures planning or responsible for attacks against Isma'ili populations, fidā'iyyūn would take reprisal action for an attack or the planning of one by placing a dagger or a note within the chambers of their opponent as a warning or even assassinating a key opponent when they deemed it necessary. Known today as Assassins, these Isma'ilis were referred to as "Hashashin" by their enemies, as many of their political enemies believed them to consume the intoxicant hashish before being dispatched as agents although modern scholarship tends to dispute this theory as polemic fabricated to discredit the Isma'ili. Other theories suggest the term originates from them being followers of "Hassan". The term entered Western vocabulary through the returning Crusaders as "assassin".

The fortress was destroyed on December 15, 1256, by Hulagu Khan as part of the Mongol offensive on Islamic Southwest Asia. The Nizari Ismailis made a critical mistake in the assassination of Genghis Khan's son, Chagatai, who ruled part of Iran. Chagatai had offended the Nizari Ismaili's by forbidding certain rituals involved in prayer and the slaughter of animals.

In 1256, the Mongols took their revenge. Most of the Nizari Ismailis were killed and their mountaintop fortresses destroyed. The Crusaders, already weakened by Mongol incursions and civil war, did not send assistance.

The last leader of the Nizari Ismaili state, Rukn al-Din Khurshah, surrendered it as part of a deal with Hulagu. However, the Mongols slaughtered the inhabitants, burnt the libraries, and brought down the fortifications. Isma'ili survivors made several attempts to recapture, and restore Alamut, and several other Isma'ili forts, but were defeated. In subsequent years, the punishment for anyone suspected of being Isma'ili would be instant death, it was common for political or social enemies to claim their rivals as secret Isma'ilis and call for their deaths.

The Isma'ili Imams, and their followers would wander Iran for several centuries in concealment, The Imams would often take on the garb of a tailor, or mystic master, and their followers as Sufi Muslims. During this period Iranian Sufism, and Isma'ilism would form a close bond. Shamsu-d-Dīn Muḥammad succeeded Ruknuddin Khwarshah as the 28th Imam, escaping as a child and living in concealment in Azerbaijan. The 29th Imam Qasim Shah, 30th Imam Islām Shāh and 31st Imam Muḥammad ibn Islām Shāh also lived in concealment. Here the Ismaili Imam became a Sufi master (murshid) and his followers mureeds which are terminologies that are used today. There is the offshoot of the Muhammad-Shahi Nizari Ismailis who follow the elder son of Shamsu-d-Dīn Muḥammad, the 28th Qasim-Shahi Imam, named ‘Alā’ ad-Dīn Mumin Shāh (26th Imam of the Muhammad-Shahi Nizari Ismailis). They follow this line of Imams until the disappearance of the 40th Imam Amir Muhammad al-Baqir in 1796. There are followers of this line of Nizari Imams in Syria today, locally called the Jafariyah.

With Safavid Iran's establishment of Twelver Islam as its official religion, many Sufi orders declared themselves to be Shi’i. Approximately one hundred years before this however, the Ismaili imamate was being transferred to the village of Anjudan, near the Shi’i centres of Qumm and Kashan. This revival is commonly termed the『Anjudān period』and constituted a revival of Ismaili political stability, for the first time since the fall of Alamut.[7] By the 15th century, a mini renaissance begins to develop in the village Anjudan near Mahallat. The Imams involved in the Anjudan Renaissance were 32nd Imam Mustanṣir billāh II, 33rd Abd al-Salam Shah and 34th Gharib Mirzā Abbas Shah. The Anjudan Renaissance ends by the 16th century with the Safavid dynasty gaining power in Iran and making Twelver Shia Islam the state religion. The Ismailis practiced taqiyyah/dissimulation as Twelver Shiites with the 36th Imam Murad Mirza being executed for political activity and the 45th Imam Shah Khalīlullāh III being murdered by a Twelver Shia mob in Yazd, Iran.

The period of the Aga Khans begins in 1817, when 45th Imam Shah Khalīl Allāh was murdered while giving refuge to his followers by a Twelver mob led by local religious leaders. His wife took her 13-year-old son and new Imam, Hassan Ali Shah to the then Qajar Emperor Shah in Tehran to seek justice. Although there was no serious penalty brought against those involved; Fath-Ali Shah Qajar gave his daughter, the princess Sarv-i Jahan, in marriage to the new Imam, and awarded him the title Agha Khan (Lord Chief). The 46th Ismāʿīlī Imām, Aga Hassan ‘Alī Shah, fled Iran in the 1840s after being blamed for a failed coup against the Shah of the Qajar dynasty. Aga Hassan ‘Alī Shah settled in Mumbai in 1848. The largest part of the Ismāʿīlī community, Qasim-Shahi Nizari today accepts Prince Karim Aga Khan IV as their 49th Imām, who they claim is descended from Muḥammad through his daughter Fāṭimah az-Zahra and 'Ali, Muḥammad's cousin and son-in-law.

Almost all Nizaris today accept Karim al-Husayni, known by his title "Aga Khan IV", as their Imām-i Zāmān "Imam/Leader of the Time", except for about 15,000 Muhammad-Shahi Nizaris in western Syria.[2] In Persian he is referred to Religiously as Khudawand (Lord of the Time), in Arabic as Mawlana (Master), or Hādhir Imām (Present Imam). Karim succeeded his grandfather Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III to the Imamate in 1957, aged just 20, and still an undergraduate at Harvard University. He was referred to as "the Imam of the Atomic age". The period following his accession can be characterized as one of rapid political and economic change. Planning of programs and institutions became increasingly difficult due to the rapid changes in newly emerging post colonial nations where many of his followers resided. Upon becoming Imam, Karim's immediate concern was the preparation of his followers, wherever they lived, for the changes that lay ahead. This rapidly evolving situation called for bold initiatives and new programs to reflect developing national aspirations, in the newly independent nations.[8]

In Africa, Asia and the Middle East, a major objective of the Community's social welfare and economic programs, until the mid-fifties, had been to create a broad base of businessmen, agriculturists, and professionals. The educational facilities of the community tended to emphasize secondary-level education. With the coming of independence, each nation's economic aspirations took on new dimensions, focusing on industrialization and modernization of agriculture. The community's educational priorities had to be reassessed in the context of new national goals, and new institutions had to be created to respond to the growing complexity of the development process.

In 1972, under the regime of the then President Idi Amin, Isma'ilis and other Asians were expelled from Uganda despite being citizens of the country and having lived there for generations. Karim undertook urgent steps to facilitate the resettlement of Isma'ilis displaced from Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya and also from Burma. Owing to his personal efforts most found homes, not only in Asia, but also in Europe and North America. Most of the basic resettlement problems were overcome remarkably rapidly. This was due to the adaptability of the Isma'ilis themselves and in particular to their educational background and their linguistic abilities, as well as the efforts of the host countries and the moral and material support from Isma'ili community programs.

In view of the importance that Islām places on maintaining a balance between the spiritual well-being of the individual and the quality of his life, the Imam's guidance deals with both aspects of the life of his followers. The Aga Khan has encouraged Isma'ili Muslims, settled in the industrialized world, to contribute towards the progress of communities in the developing world through various development programs. Indeed, the Economist noted: that Isma'ili immigrant communities, integrated seamlessly as an immigrant community, and did better at attaining graduate and post graduate degrees, "far surpassing their native, Hindu, Sikh, fellow Muslims, and Chinese communities".[9]

In recent years, Isma'ili Muslims, who have come to the US, Canada and Europe, mostly as refugees from Asia and Africa, have readily settled into the social, educational and economic fabric of urban and rural centers across the two continents. As in the developing world, the Isma'ili Muslim community's settlement in the industrial world has involved the establishment of community institutions characterized by an ethos of self-reliance, an emphasis on education, and a pervasive spirit of philanthropy. Spiritual allegiance to the Imam and adherence to the Nizari tariqa according to the guidance of the Imam of the time, have engendered in the Isma'ili community an ethos of self-reliance, unity, and a common identity notwithstanding centuries of being marginalized and persecuted by native and established societies.

Notable Isma'ili include:

From July 1982 to July 1983, to celebrate the present Aga Khan's Silver Jubilee, marking the 25th anniversary of his accession to the Imamate, many new social and economic development projects were launched. These range from the establishment of the US$300 million international Aga Khan University with its Faculty of Health Sciences and teaching hospital based in Karachi, the expansion of schools for girls and medical centers in the Hunza region, one of the remote parts of Northern Pakistan bordering on China and Afghanistan, to the establishment of the Aga Khan Rural Support Program in Gujarat, India, and the extension of existing urban hospitals and primary health care centers in Tanzania and Kenya. These initiatives form part of an international network of institutions involved in fields that range from education, health and rural development, to architecture and the promotion of private sector enterprise and together make up the Aga Khan Development Network.

It is this commitment to man's dignity and relief of humanity that inspires the Isma'ili Imamate's philanthropic institutions. Giving of one's competence, sharing one's time, material or intellectual ability with those among whom one lives, for the relief of hardship, pain or ignorance is a deeply ingrained tradition which shapes the social conscience of the Isma'ili Muslim community.

During his Golden Jubilee from 2007–2008 marking 50 years of Imamate the Aga Khan commissioned a number of projects, renowned Pritzker Prize winning Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki was commissioned to design a new kind of community structure resembling an embassy in Canada, The "Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat" opened on 8 December 2008, the building will be composed of two large interconnected spaces an atrium and a courtyard. The atrium is an interior space to be used all year round. It is protected by a unique glass dome made of multi-faceted, angular planes assembled to create the effect of rock crystal the Aga Khan asked Maki to consider the qualities of "rock crystal" in his design, which during the Fatimid Caliphate was valued by the Imams. Within the glass dome is an inner layer of woven glass-fibre fabric which will appear to float and hover over the atrium. The Delegation building sits along Sussex drive near the Canadian parliament. Future Delegation buildings are planned for other capitals, beginning with Lisbon, Portugal.

In addition to primary and secondary schools, the Aga Khan Academies were set up to equip future leaders in the developing world with a leading standard education. The Aga Khan Museum, which opened in Toronto, Ontario, Canada in 2011, is the first museum dedicated to Islamic civilization in the west. Its mission is the "acquisition, preservation and display of artefacts – from various periods and geographies – relating to the intellectual, cultural, artistic and religious heritage of Islamic communities". A series of new Isma'ili centre are underway, including Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Paris, France; Houston, Texas; Dushanbe and the Pamirs; Tajikistan.

From 11 July 2017 to 11 July 2018 was designated as the diamond jubilee year of the Aga Khan IV's 60th year of reign. The Aga Khan travelled throughout the diamond jubilee year to countries where his humanitarian institutions operate to launch new programs that help alleviate poverty and increase access to education, housing and childhood development. The Aga Khan's diamond jubilee opening ceremony was held in Dubai. On March 8, 2018, Queen Elizabeth hosted the Aga Khan at Windsor Castle at a dinner to mark his diamond jubilee. During this important time he visited his murids around the world. He has already visited the United States, UAE, India, Pakistan, and Kenya during his diamond jubilee Mulaqat's. During his visit to Houston, he announced The Ismaili Centre Houston. The Aga Khan resided in Canada in early May 2018. His diamond jubilee came to an end at Lisbon, where a big festival was held. The festival included a Mulaqat for all the Nizari Ismaili Muslims around the world. Many performances and events were held around July 11, 2018, which was the Imamat day of the Aga Khan. Following a historic agreement with the Republic of Portugal in 2015, His Highness the Aga Khan officially designated the premises located at Rua Marquês de Fronteira in Lisbon – the Henrique de Mendonça Palace – as the seat of the Ismaili Imamat on July 11, 2018, and declared that it be known as the “Diwan of the Ismaili Imamat".

| # | Imam | Imamate period (CE) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isma'ili and Twelver Imams | |||

| 1 | 'Alī ibn Abī Tālib | 632–661 | First Shia Isma'ili Imam and Fourth Rashidun Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate |

| Hasan | 624–670 | son of Ali (viewed as a temporary Imam by the Nizari), 5th Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate | |

| 2 | Husayn | 661–680 | son of Ali, martyred at Karbala, all Shia Imams must come from his male progeny, offshoot of the Kaysanites |

| 3 | 'Alī Zayn al-Ābidīn | 680–713 | son of Husain, ascetic and pious, composes the Sahifa al-Sajjadiyya |

| 4 | Muḥammad al-Bāqir | 713–743 | son of Ali Zayn al-Ābidīn, ascetic and pious, defines fiqh, offshoot of the Zaidiyyah |

| 5 | Ja'far aṣ-Ṣādiq | 743–765 | son of Muhammad, defines Imamate in Shia doctrine, offshoot of the Fathites, Bazighiyya and Tawussite Shia |

| Isma'iliyah and Ithna' Ashariya split | |||

| 6 | Ismā'īl bin Jafar | 702–755 | Jafar's son and designated heir, accepted as Imam by the Ismailis, offshoot of the Sevener |

| 7 | Muhammad ibn Ismā'īl | 765–813 | Ismail's son, goes into hiding and dies in Salamiyah in Syria, offshoot of the Qaramita |

| First Period of Concealment or Dawr al Satr | |||

| 8 | ʿAbd Allāh Wafī Aḥmad | 806–828 | also known as ʿAbadullāh, based in Salamiyah |

| 9 | Aḥmad Taqī Muḥammad | 828–870 | son of ʿAbd Allāh, based in Salamiyah |

| 10 | Ḥusayn Radhī ad-dīn ʿAbd Allāh | 870–881 | son of Aḥmad, based in Salamiyah |

| Fatimid Caliphate | |||

| 11 | Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah | 881–934 | openly announced himself as Imam, first Fatimid Caliph, founded and based in Mahdia |

| 12 | Muḥammad al-Qā'im bi-'Amrillāh | 934–946 | second Fatimid Caliph, based in Mahdia |

| 13 | Abū Ṭāhir Ismā'il al-Manṣūr bi-llāh | 946–953 | third Fatimid Caliph, based in Raqqada |

| 14 | Maʿād al-Muʿizz li-Dīnillāh | 953–975 | fourth Fatimid Caliph, founded and based in Cairo |

| 15 | Abū Manṣūr Nizār al-ʿAzīz billāh | 975–996 | fifth Fatimid Caliph, based in Cairo |

| 16 | Al-Ḥakīm bi-Amri 'l-llāh | 996–1021 | sixth Fatimid Caliph, based in Cairo, disappeared 1021. The Druze believe in the divinity of Al-Hakim's disappearance, believed by them to be the occultation of the Mahdi. |

| 17 | ʿAlī az-Zāhir li-Iʿzāz Dīnillāh | 1021–1036 | son of al-Hakim, seventh Fatimid Caliph, based in Cairo |

| 18 | Abū Tamīm Ma'add al-Mustanṣir bi-llāh | 1036–1094 | eighth Fatimid Caliph, based in Cairo |

| Nizari Ismaili Imāmincaptivity | |||

| 19 | Nizar (Fatimid Imam) | 1094–1095 | son of al-Mustansir, based in Cairo and Alexandria, rebels against Al-Musta'li but fails and died in prison, offshoot of the Musta'li sect |

| Concealed ImāmsofAlamūt: Second Period of Concealment or Dawr al Satr | |||

| 20 | Husayn Ali al-Hādī | 1095–1132 | escapes to Alamut CastleinAlamut with a Nizari Da'i Abul Hasan Saidi from Egypt |

| 21 | Muḥammad I al-Muhtadī | 1132–1162 | based in Alamut Castle |

| 22 | Ḥassan I al-Qāhir bi-Quwwatu'llāh | 1161–1164 | based in Alamut Castle |

| Sultans of Alamut based at Alamut Castle, governing the Nizari Ismaili State | |||

| 23 | Ḥassan II | 1164–1166 | Son of Imam al-Qahir and the first Nizari Ismaili Imam of Alamut to openly declare himself as such, murdered, based in Alamut Castle |

| 24 | Nūr ad-Dīn Muḥammad II | 1166–1210 | Son of Hassan II, openly declared himself the Imam, murdered, based in Alamut Castle |

| 25 | Jalāl ad-Dīn Ḥassan III | 1210–1221 | Son of Nur ad-Din Muhammad II, adopts the Sunni Shafi‘i madhhab as Taqiya, based in Alamut Castle |

| 26 | ‘Alā’ ad-Dīn Muḥammad III | 1221–1255 | Son of Jalal ad-Din Hasan, based in Alamut Castle |

| 27 | Rukn al-Din Khurshah | 1255–1257 | Son of Muhammad III and last Lord of Alamut; surrendered to Hulagu Khan in 1256; travelled to the court of Kublai Khan but was murdered on the journey back in 1257, based in Alamut Castle. |

| Third Period of Concealment | |||

| 28 | Shamsu-d-Dīn Muḥammad | 1257–1310 | adopts SufismasTaqiya, based in Tabriz, Azerbaijan |

| 29 | Qasim Shah | 1310–1368 | adopts Sufism as Taqiya, based in Tabriz, Azerbaijan, Offshoot of the Muhammad-Shahi or Mumini Nizari sect |

| 30 | Islām Shāh | 1368–1424 | adopts Sufism as Taqiya, based in Kahak |

| 31 | Muḥammad ibn Islām Shāh | 1424–1464 | adopts Sufism as Taqiya, based in Kahak |

| Anjudan Renaissance – The Nizari Ismaili Imams are based in the village of Anjudan near Qom and Kashan in Iran | |||

| 32 | ‘Ali Shah Qalandar Mustansir bi’llah II | 1464–1480 | adopts Sufism as Taqiya, based in Anjudan |

| 33 | Abd-us-Salam Shah | 1480–1494 | adopts Sufism as Taqiya, based in Anjudan |

| 34 | Gharib Mirzā Abbas Shah | 1494–1498 | adopts Sufism as Taqiya, based in Anjudan |

| Anjudan Renaissance ends, The Twelver Shia rule of the Safavids, Fourth Period of Concealment | |||

| 35 | Abū Dharr ʿAlī Nūru-d-Dīn (Nur Shah) | 1498–1509 | adopts Twelver Shiaastaqiyya, based in Anjudan |

| 36 | Murād Mīrzā | 1509–1574 | adopts Twelver Shia as taqiyya, based in Anjudan, offshoot of Satpanth |

| 37 | Dhu al-Fiqār ʿAlī Khalīlullāh I | 1574–1634 | adopts Twelver Shia as taqiyya, based in Anjudan |

| 38 | Nūr ad-Dahr (Nūr ad-Dīn) ʿAlī | 1634–1671 | adopts Twelver Shia as taqiyya, based in Anjudan |

| 39 | Khalīl Allāh II ʿAlī | 1671–1680 | adopts Twelver Shia as taqiyya, based in Anjudan |

| 40 | Shāh Nizār II | 1680–1722 | adopts Twelver Shia as taqiyya, based in Kahak |

| 41 | Sayyid ʿAlī | 1722–1736 | adopts Twelver Shia as taqiyya, based in Kahak |

| 42 | Sayyid Hasan ‘Ali Beg | 1736–1747 | adopts Twelver Shia as taqiyya, based in Kahak |

| 43 | Qāsim ʿAlī (Sayyid Jaʿfar) | 1747–1756 | adopts Twelver Shia as taqiyya, based in Kahak |

| 44 | Sayyid Abu’l-Hasan ‘Ali (Bāqir Shāh) | 1756–1792 | adopts Twelver Shia as taqiyya, based in Kahak |

| 45 | Shāh Khalīlullāh III | 1792–1817 | adopts Twelver Shia as taqiyya, later murdered by a Twelver Shia mob in Yazd, Iran |

| The Aga Khans starting from 1817 | |||

| 46 | Aga Khan I | 1817–1881 | Born in Kahak, the first Nizari Ismaili Imam given the title of Aga KhanbyFath-Ali Shah Qajar. Rebels against Mohammad Shah Qajar but is defeated and joins the British in Herat, Afghanistan to defend them from bandits and they, in turn, help him return to Persia. Dies in Mumbai, India and buried in Hasanabad. |

| 47 | Aga Khan II | 1881–1885 | son of Aga Khan I, born in Mahallat, based in Mumbai and buried in Najaf. |

| 48 | Aga Khan III | 1885–1957 | son of Aga Khan II, born in Karachi, died in Versoix near Geneva, Switzerland buried in the Mausoleum of Aga Khan, Aswan, Egypt. |

| 49 | Shāh Karīm-al-Ḥussaynī, His Highness Prince Karīm Āgā Khān IV | 1957–present | born in Geneva, Switzerland based at the Aiglemont estateinGouvieux in the Picardie region of France and in Lisbon, Portugal. |