From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Chinese military general and official (140 BC – 117 BC)

H u o Q u b i n g ( 1 4 0 B C – c . O c t o b e r 1 1 7 B C , [ 1 ] f o r m e r l y H o C h ' i i - p i n g ) w a s a C h i n e s e m i l i t a r y g e n e r a l a n d p o l i t i c i a n o f t h e W e s t e r n H a n d y n a s t y d u r i n g t h e r e i g n o f E m p e r o r W u o f H a n . H e w a s a n e p h e w o f t h e g e n e r a l W e i Q i n g a n d E m p r e s s W e i Z i f u ( E m p e r o r W u ' s w i f e ) , a n d a h a l f - b r o t h e r o f t h e s t a t e s m a n H u o G u a n g . [ 2 ] A l o n g w i t h W e i Q i n g , h e l e d a c a m p a i g n i n t o t h e G o b i D e s e r t o f w h a t i s n o w M o n g o l i a t o d e f e a t t h e X i o n g n u n o m a d i c c o n f e d e r a t i o n , w i n n i n g d e c i s i v e v i c t o r i e s s u c h a s t h e B a t t l e o f M o b e i i n 1 1 9 B C .

H u o Q u b i n g w a s o n e o f t h e m o s t l e g e n d a r y c o m m a n d e r s i n C h i n e s e h i s t o r y , a n d s t i l l l i v e s o n i n C h i n e s e c u l t u r e t o d a y .

E a r l y l i f e [ e d i t ] H u o Q u b i n g w a s a n i l l e g i t i m a t e s o n f r o m t h e l o v e a f f a i r b e t w e e n W e i S h a o e r ( 衛 少 兒 ) , t h e d a u g h t e r o f a l o w l y m a i d f r o m t h e h o u s e h o l d o f P r i n c e s s P i n g y a n g ( E m p e r o r W u ' s o l d e r s i s t e r ) , a n d H u o Z h o n g r u ( 霍 仲 孺 ) , a l o w - r a n k i n g c i v i l s e r v a n t e m p l o y e d t h e r e a t t h e t i m e . [ 3 ] H o w e v e r , H u o Z h o n g r u d i d n o t w a n t t o m a r r y a l o w e r c l a s s s e r f g i r l l i k e W e i S h a o e r , s o h e a b a n d o n e d h e r a n d w e n t a w a y t o m a r r y a w o m a n f r o m h i s h o m e t o w n i n s t e a d . W e i S h a o e r i n s i s t e d o n k e e p i n g t h e c h i l d , r a i s i n g h i m w i t h h e l p o f h e r s i b l i n g s .

W h e n H u o Q u b i n g w a s a r o u n d t w o y e a r s o l d , h i s y o u n g e r a u n t W e i Z i f u , w h o w a s s e r v i n g a s a n i n - h o u s e s i n g e r / d a n c e r f o r P r i n c e s s P i n g y a n g , c a u g h t t h e a t t e n t i o n o f t h e y o u n g E m p e r o r W u , w h o t o o k h e r a n d h e r h a l f - b r o t h e r W e i Q i n g b a c k t o h i s p a l a c e i n t h e c a p i t a l , C h a n g ' a n . M o r e t h a n a y e a r l a t e r , t h e n e w l y f a v o u r e d c o n c u b i n e W e i Z i f u b e c a m e p r e g n a n t w i t h E m p e r o r W u ' s f i r s t c h i l d , e a r n i n g h e r t h e j e a l o u s y a n d h a t r e d o f E m p e r o r W u ' s t h e n e m p r e s s c o n s o r t , E m p r e s s C h e n . E m p r e s s C h e n ' s m o t h e r , G r a n d P r i n c e s s [ 4 ] G u a n t a o ( 館 陶 長 公 主 ) , t h e n a t t e m p t e d t o r e t a l i a t e a g a i n s t W e i Z i f u b y k i d n a p p i n g a n d a t t e m p t i n g t o m u r d e r W e i Q i n g , w h o w a s t h e n s e r v i n g a s a h o r s e m a n a t t h e J i a n z h a n g C a m p ( 建 章 營 , E m p e r o r W u ' s r o y a l g u a r d s ) . A f t e r W e i Q i n g w a s r e s c u e d b y f e l l o w p a l a c e g u a r d s l e d b y h i s c l o s e f r i e n d G o n g s u n A o ( 公 孫 敖 ) , E m p e r o r W u t o o k t h e o p p o r t u n i t y t o h u m i l i a t e E m p r e s s C h e n a n d P r i n c e s s G u a n t a o b y p r o m o t i n g W e i Z i f u t o a c o n s o r t ( 夫 人 , a c o n c u b i n e p o s i t i o n l o w e r o n l y t o t h e E m p r e s s ) a n d W e i Q i n g t o t h e t r i p l e r o l e o f C h i e f o f J i a n z h a n g C a m p ( 建 章 監 ) , C h i e f o f S t a f f ( 侍 中 ) , a n d C h i e f C o u n c i l l o r ( 太 中 大 夫 ) , e f f e c t i v e l y m a k i n g h i m o n e o f E m p e r o r W u ' s c l o s e s t l i e u t e n a n t s . T h e r e s t o f t h e W e i f a m i l y w e r e a l s o w e l l r e w a r d e d , i n c l u d i n g t h e d e c r e e d m a r r i a g e o f W e i S h a o e r ' s o l d e r s i s t e r W e i J u n r u ( 衛 君 孺 ) t o E m p e r o r W u ' s a d v i s e r , G o n g s u n H e ( 公 孫 賀 ) . A t t h e t i m e , W e i S h a o e r w a s r o m a n t i c a l l y e n g a g e d w i t h C h e n Z h a n g ( 陳 掌 ) , a g r e a t - g r a n d s o n o f E m p e r o r G a o z u ' s a d v i s e r C h e n P i n g . T h e i r r e l a t i o n s h i p w a s a l s o l e g i t i m i z e d b y E m p e r o r W u t h r o u g h t h e f o r m o f d e c r e e d m a r r i a g e . [ 5 ] T h r o u g h t h e r i s e o f t h e W e i f a m i l y , t h e y o u n g H u o Q u b i n g g r e w u p i n p r o s p e r i t y a n d p r e s t i g e .

M i l i t a r y c a r e e r [ e d i t ] H u o Q u b i n g e x h i b i t e d o u t s t a n d i n g m i l i t a r y t a l e n t e v e n a s a t e e n a g e r . E m p e r o r W u s a w H u o ' s p o t e n t i a l a n d m a d e H u o h i s p e r s o n a l a s s i s t a n t .

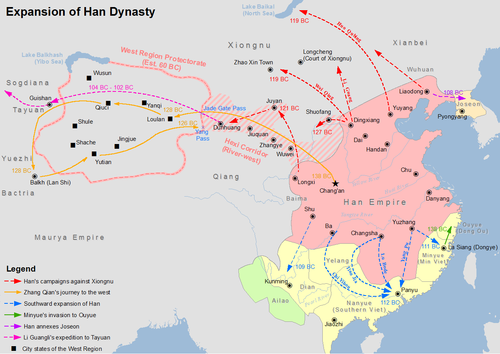

H u o Q u b i n g ' s c a m p a i g n a g a i n s t X i o n g n u i s s h o w n i n r e d

I n 1 2 3 B C , E m p e r o r W u s e n t W e i Q i n g f r o m D i n g x i a n g ( 定 襄 ) t o e n g a g e t h e i n v a d i n g X i o n g n u , a n d a p p o i n t e d t h e 1 8 - y e a r - o l d H u o Q u b i n g t o s e r v e a s t h e C a p t a i n o f P i a o y a o ( 票 姚 校 尉 ) u n d e r h i s u n c l e , [ 6 ] s e e i n g r e a l c o m b a t f o r t h e f i r s t t i m e . A l t h o u g h W e i Q i n g w a s a b l e t o k i l l o r c a p t u r e m o r e t h a n 1 0 , 0 0 0 X i o n g n u s o l d i e r s , p a r t o f h i s v a n g u a r d f o r c e s , a 3 , 0 0 0 - s t r o n g r e g i m e n t c o m m a n d e d b y g e n e r a l s S u J i a n ( 蘇 建 , f a t h e r o f t h e H a n d i p l o m a t a n d s t a t e s m a n , S u W u ) a n d Z h a o X i n ( 趙 信 , a s u r r e n d e r e d X i o n g n u p r i n c e ) w a s o u t n u m b e r e d a n d a n n i h i l a t e d a f t e r e n c o u n t e r i n g t h e X i o n g n u f o r c e l e d b y Y i z h i x i e C h a n y u ( 伊 稚 斜 單 于 ) . Z h a o X i n d e f e c t e d o n t h e f i e l d w i t h h i s 8 0 0 e t h n i c X i o n g n u s u b o r d i n a t e s , w h i l e S u J i a n e s c a p e d a f t e r l o s i n g a l l h i s m e n i n t h e d e s p e r a t e f i g h t i n g . D u e t o t h e l o s s o f t h i s d e t a c h m e n t , W e i Q i n g ' s t r o o p s d i d n o t e a r n a n y p r o m o t i o n , b u t H u o Q u b i n g d i s t i n g u i s h e d h i m s e l f b y l e a d i n g a l o n g - d i s t a n c e s e a r c h - a n d - d e s t r o y m i s s i o n w i t h 8 0 0 l i g h t c a v a l r y m e n , [ 7 ] k i l l i n g t h e C h a n y u ' s g r a n d f a t h e r a n d o v e r 2 , 0 0 0 e n e m y t r o o p s , a s w e l l a s c a p t u r i n g n u m e r o u s X i o n g n u n o b l e s . A v e r y i m p r e s s e d E m p e r o r W u t h e n m a d e H u o Q u b i n g t h e M a r q u e s s o f G u a n j u n ( C h a m p i o n ) ( 冠 軍 侯 ) w i t h a m a r c h o f 2 , 5 0 0 h o u s e h o l d s . [ 8 ] I n 1 2 1 B C , E m p e r o r W u d e p l o y e d H u o Q u b i n g t w i c e i n t h a t y e a r a g a i n s t t h e X i o n g n u i n t h e H e x i C o r r i d o r . D u r i n g s p r i n g , H u o Q u b i n g l e d 1 0 , 0 0 0 c a v a l r y , f o u g h t t h r o u g h f i v e W e s t e r n R e g i o n s k i n g d o m s w i t h i n 6 d a y s , a d v a n c e d o v e r 1 , 0 0 0 li o v e r M o u n t Y a n z h i ( 焉 支 山 ) , k i l l e d t w o X i o n g n u p r i n c e s a l o n g w i t h n e a r l y 9 , 0 0 0 e n e m y t r o o p s , a n d c a p t u r e d s e v e r a l X i o n g n u n o b l e s a s w e l l a s t h e G o l d e n M a n i d o l u s e d b y X i o n g n u a s a n a r t i f a c t f o r h o l y r i t u a l s . [ 9 ] F o r t h i s a c h i e v e m e n t , h i s m a r c h w a s i n c r e a s e d b y 2 , 2 0 0 h o u s e h o l d s . [ 1 0 ] D u r i n g t h e s u m m e r o f t h e s a m e y e a r , X i o n g n u a t t a c k e d t h e D a i C o m m a n d e r y a n d Y a n m e n . H u o Q u b i n g s e t o f f f r o m L o n g x i ( m o d e r n - d a y G a n s u ) w i t h o v e r 1 0 , 0 0 0 c a v a l r y , s u p p o r t e d b y G o n g s u n A o , w h o s e t o f f f r o m t h e B e i d i C o m m a n d e r y ( 北 地 郡 ) . D e s p i t e G o n g s u n A o f a i l i n g t o k e e p u p , H u o Q u b i n g t r a v e l l e d o v e r 2 , 0 0 0 li w i t h o u t b a c k u p , a l l t h e w a y p a s t J u y a n L a k e to Q i l i a n M o u n t a i n s , k i l l i n g o v e r 3 0 , 0 0 0 X i o n g n u s o l d i e r s a n d c a p t u r i n g a d o z e n X i o n g n u p r i n c e s . H i s m a r c h w a s t h e n i n c r e a s e d f u r t h e r b y a n a d d i t i o n a l 5 , 4 0 0 h o u s e h o l d s f o r t h e v i c t o r y .

T o m b o f H u o Q u b i n g , s t a t u e o f a h o r s e s t o m p i n g a X i o n g n u w a r r i o r , w i t h d e t a i l o f t h e h e a d o f t h e v a n q u i s h e d X i o n g n u w a r r i o r . [ 1 1 ] [ 1 2 ] H u o Q u b i n g ' s v i c t o r i e s d e a l t h e a v y b l o w s t o t h e t r i b e s o f t h e X i o n g n u p r i n c e s o f H u n x i e ( 渾 邪 王 ) a n d X i u t u ( 休 屠 王 ) t h a t o c c u p i e d t h e H e x i C o r r i d o r . O u t o f f r u s t r a t i o n , Y i z h i x i e C h a n y u w a n t e d t o m e r c i l e s s l y e x e c u t e t h o s e t w o p r i n c e s a s p u n i s h m e n t . T h e P r i n c e o f H u n x i e c o n t a c t e d t h e H a n g o v e r n m e n t i n a u t u m n o f 1 2 1 B C t o n e g o t i a t e a s u r r e n d e r . F a i l i n g t o p e r s u a d e h i s f e l l o w p r i n c e t o d o t h e s a m e , h e k i l l e d t h e P r i n c e o f X i u t u a n d o r d e r e d X i u t u ' s f o r c e s t o a l s o s u r r e n d e r . W h e n t h e t w o t r i b e s w e n t t o m e e t t h e H a n f o r c e s , X i u t u ' s f o r c e s r i o t e d . S e e i n g t h e s i t u a t i o n c h a n g e d , H u o Q u b i n g a l o n e h e a d e d t o t h e X i o n g n u c a m p . T h e r e , t h e g e n e r a l o r d e r e d t h e P r i n c e o f H u n x i e t o c a l m h i s m e n a n d s t a n d d o w n b e f o r e p u t t i n g d o w n 8 , 0 0 0 X i o n g n u m e n w h o r e f u s e d t o d i s a r m , e f f e c t i v e l y q u e l l i n g t h e r i o t . T h e H u n x i e t r i b e w a s t h e n r e s e t t l e d i n t o t h e C e n t r a l P l a i n . T h e s u r r e n d e r o f t h e X i u t u a n d H u n x i e t r i b e s s t r i p p e d X i o n g n u o f a n y c o n t r o l o v e r t h e W e s t e r n R e g i o n s , d e p r i v i n g t h e m o f a l a r g e g r a z i n g a r e a . A s a r e s u l t , t h e H a n d y n a s t y s u c c e s s f u l l y o p e n e d u p t h e N o r t h e r n S i l k R o a d , a l l o w i n g d i r e c t t r a d e a c c e s s t o C e n t r a l A s i a . T h i s a l s o p r o v i d e d a n e w s u p p l y o f h i g h - q u a l i t y h o r s e b r e e d s f r o m C e n t r a l A s i a , i n c l u d i n g t h e f a m e d F e r g h a n a h o r s e ( a n c e s t o r s o f t h e m o d e r n A k h a l - T e k e ) , f u r t h e r s t r e n g t h e n i n g t h e H a n a r m y . E m p e r o r W u t h e n r e i n f o r c e d t h i s s t r a t e g i c a s s e t b y e s t a b l i s h i n g f i v e c o m m a n d e r i e s a n d c o n s t r u c t i n g a l e n g t h o f f o r t i f i e d w a l l a l o n g t h e b o r d e r o f t h e H e x i C o r r i d o r . H e c o l o n i s e d t h e a r e a w i t h 7 0 0 , 0 0 0 C h i n e s e s o l d i e r - s e t t l e r s .

A f t e r t h e s e r i e s o f d e f e a t s b y W e i Q i n g a n d H u o Q u b i n g , Y i z h i x i e C h a n y u t o o k Z h a o X i n ' s a d v i c e a n d r e t r e a t e d w i t h h i s t r i b e s t o t h e n o r t h o f t h e G o b i D e s e r t , h o p i n g t h a t t h e b a r r e n l a n d w o u l d s e r v e a s a n a t u r a l b a r r i e r a g a i n s t H a n o f f e n s i v e s . E m p e r o r W u h o w e v e r , w a s f a r f r o m g i v i n g u p , a n d p l a n n e d a m a s s i v e e x p e d i t i o n a r y c a m p a i g n i n 1 1 9 B C . H a n f o r c e s w e r e d e p l o y e d i n t w o s e p a r a t e c o l u m n s , e a c h c o n s i s t i n g o f 5 0 , 0 0 0 c a v a l r y a n d o v e r 1 0 0 , 0 0 0 i n f a n t r y , w i t h W e i Q i n g a n d H u o Q u b i n g s e r v i n g a s t h e s u p r e m e c o m m a n d e r f o r e a c h .

E m p e r o r W u , w h o h a d b e e n d i s t a n c i n g W e i Q i n g a n d g i v i n g t h e y o u n g e r H u o Q u b i n g m o r e a t t e n t i o n a n d f a v o u r , h o p e d t h a t H u o w o u l d e n g a g e t h e s t r o n g e r C h a n y u ' s t r i b e a n d p r e f e r e n t i a l l y a s s i g n e d h i m t h e m o s t e l i t e t r o o p e r s . T h e i n i t i a l p l a n c a l l e d f o r H u o Q u b i n g t o a t t a c k f r o m D i n g x i a n g ( 定 襄 , m o d e r n - d a y Q i n g s h u i h e C o u n t y , I n n e r M o n g o l i a ) a n d e n g a g e t h e C h a n y u , w i t h W e i Q i n g s u p p o r t i n g h i m i n t h e e a s t f r o m D a i C o m m a n d e r y ( 代 郡 , m o d e r n - d a y , Y u C o u n t y , H e b e i ) t o e n g a g e t h e L e f t W o r t h y P r i n c e ( 左 賢 王 ) . H o w e v e r , a X i o n g n u p r i s o n e r o f w a r c o n f e s s e d t h a t t h e C h a n y u ' s m a i n f o r c e w a s a t t h e e a s t s i d e . U n a w a r e t h a t t h i s w a s a c t u a l l y f a l s e i n f o r m a t i o n p r o v i d e d b y t h e X i o n g n u , E m p e r o r W u o r d e r e d t h e t w o c o l u m n s t o s w i t c h r o u t e s , w i t h W e i Q i n g n o w s e t t i n g o f f o n t h e w e s t e r n s i d e f r o m D i n g x i a n g , a n d H u o Q u b i n g m a r c h i n g o n t h e e a s t e r n s i d e f r o m t h e D a i C o m m a n d e r y .

B a t t l e s a t t h e e a s t e r n D a i C o m m a n d e r y t h e a t r e w e r e q u i t e s t r a i g h t f o r w a r d , a s H u o Q u b i n g ' s f o r c e s w e r e f a r s u p e r i o r t o t h e i r e n e m i e s . H u o Q u b i n g a d v a n c e d o v e r 2 , 0 0 0 li a n d d i r e c t l y e n g a g e d t h e L e f t W o r t h y P r i n c e i n a s w i f t a n d d e c i s i v e b a t t l e . H e q u i c k l y e n c i r c l e d a n d o v e r r a n t h e X i o n g n u , k i l l i n g o v e r 7 0 , 0 0 0 m e n , a n d c a p t u r i n g t h r e e l o r d s a n d 8 3 n o b l e s , w h i l e s u f f e r i n g a 2 0 % c a s u a l t y r a t e t h a t w a s q u i c k l y r e s u p p l i e d f r o m l o c a l c a p t i v e s . H e t h e n w e n t o n t o c o n d u c t a s e r i e s o f r i t u a l s u p o n h i s a r r i v a l a t t h e K h e n t i i M o u n t a i n s ( 狼 居 胥 山 , a n d t h e m o r e n o r t h e r n 姑 衍 山 ) t o s y m b o l i z e t h e h i s t o r i c H a n v i c t o r y , t h e n c o n t i n u e d h i s p u r s u i t a s f a r a s L a k e B a i k a l ( 瀚 海 ) , e f f e c t i v e l y a n n i h i l a t i n g t h e X i o n g n u c l a n a n d a l l o w i n g c o n q u e r i n g t r i b e s u c h a s t h e D o n g h u P e o p l e t o r e t a k e b a c k t h e i r l a n d t o e s t a b l i s h t h e i r o w n c o n f e d e r a c y t o d e c l a r e d i n d e p e n d e n t f r o m X i o n g n u O v e r l o r d f o l l o w i n g t h e s u b j u g a t i o n f o r o v e r a f e w d e c a d e . [ 1 3 ] A s e p a r a t e d i v i s i o n l e d b y L u B o d e ( 路 博 德 ) , s e t o f f o n a s t r a t e g i c a l l y f l a n k i n g r o u t e f r o m R i g h t B e i p i n g ( 右 北 平 , m o d e r n - d a y N i n g c h e n g C o u n t y , I n n e r M o n g o l i a ) , j o i n e d f o r c e s w i t h H u o Q u b i n g a f t e r a r r i v i n g i n t i m e w i t h 2 , 8 0 0 e n e m y k i l l s , a n d t h e c o m b i n e d f o r c e s t h e n r e t u r n e d i n t r i u m p h . T h i s v i c t o r y e a r n e d H u o Q u b i n g 5 , 8 0 0 h o u s e h o l d s o f f i e f d o m a s a r e w a r d , [ 1 4 ] m a k i n g h i m m o r e d i s t i n g u i s h e d t h a n h i s u n c l e W e i Q i n g . [ 1 5 ] A t t h e h e i g h t o f h i s c a r e e r , m a n y l o w - r a n k i n g c o m m a n d e r s p r e v i o u s l y s e r v e d u n d e r W e i Q i n g v o l u n t a r i l y t r a n s f e r r e d t o H u o Q u b i n g ' s s e r v i c e i n t h e h o p e o f a c h i e v i n g m i l i t a r y g l o r y w i t h h i m . [ 1 6 ] D e a t h a n d l e g a c y [ e d i t ] T o m b o f H u o Q u b i n g i n 1 9 1 4 , S h a a n x i , C h i n a , p h o t o g r a p h e d b y V i c t o r S e g a l e n ( 1 8 7 8 – 1 9 1 9 ) . T h e " H o r s e S t o m p i n g X i o n g n u " s t a t u e a p p e a r s i n f r o n t .

T h e " H o r s e S t o m p i n g X i o n g n u " s t a t u e a t H u o Q u b i n g ' s t o m b

E m p e r o r W u o f f e r e d t o h e l p H u o Q u b i n g b u i l d u p a h o u s e h o l d f o r m a r r i a g e . H u o Q u b i n g , h o w e v e r , a n s w e r e d t h a t " t h e X i o n g n u a r e n o t y e t e l i m i n a t e d , w h y s h o u l d I s t a r t a f a m i l y ? " ( 匈 奴 未 滅 , 何 以 家 為 ? ) , [ 1 7 ] a s t a t e m e n t t h a t b e c a m e a n i n s p i r a t i o n a l C h i n e s e p a t r i o t i c m o t t o . T h o u g h H u o Q u b i n g w a s r e c o r d e d a s a q u i e t l y s p o k e n m a n o f f e w w o r d s , h e w a s f a r f r o m h u m b l e . [ 1 8 ] S i m a Q i a n n o t e d i n S h i j i t h a t H u o Q u b i n g p a i d l i t t l e r e g a r d t o h i s m e n , [ 1 9 ] r e f u s i n g t o s h a r e h i s f o o d w i t h h i s s o l d i e r s , [ 2 0 ] a n d r e g u l a r l y o r d e r i n g h i s t r o o p s t o c o n d u c t c u j u g a m e s d e s p i t e t h e m b e i n g s h o r t o n r a t i o n s . [ 2 1 ] W h e n E m p e r o r W u s u g g e s t e d h i m t o s t u d y T h e A r t o f W a r by S u n T z u a n d W u z i by W u Q i , H u o Q u b i n g c l a i m e d t h a t h e n a t u r a l l y u n d e r s t o o d w a r s t r a t e g i e s a n d h a d n o n e e d t o s t u d y . [ 2 2 ] W h e n h i s s u b o r d i n a t e L i G a n ( 李 敢 , s o n o f L i G u a n g ) a s s a u l t e d W e i Q i n g , t h e l a t t e r f o r g a v e t h e i n c i d e n t . H u o Q u b i n g , o n t h e o t h e r h a n d , r e f u s e d t o t o l e r a t e s u c h d i s r e s p e c t t o w a r d s h i s u n c l e a n d p e r s o n a l l y s h o t L i G a n d u r i n g a h u n t i n g t r i p . E m p e r o r W u c o v e r e d f o r Q u b i n g , s t a t i n g t h a t L i G a n w a s " k i l l e d b y a d e e r " . [ 2 3 ] W h e n i t c a m e t o m i l i t a r y g l o r y , H u o Q u b i n g w a s s a i d t o b e m o r e g e n e r o u s . O n e s t o r y a b o u t h i m t o l d o f w h e n E m p e r o r W u a w a r d e d H u o a j a r o f p r e c i o u s w i n e f o r h i s a c h i e v e m e n t , h e p o u r e d i t i n t o a c r e e k s o a l l h i s m e n d r i n k i n g t h e w a t e r c o u l d s h a r e a t a s t e o f i t , g i v i n g t h e n a m e t o t h e c i t y o f J i u q u a n ( 酒 泉 , l i t e r a l l y " w i n e s p r i n g " ) .

H u o Q u b i n g d i e d i n 1 1 7 B C a t t h e e a r l y a g e o f 2 3 . A f t e r H u o Q u b i n g ' s d e a t h , t h e a g g r i e v e d E m p e r o r W u o r d e r e d t h e e l i t e t r o o p s f r o m t h e f i v e b o r d e r c o m m a n d e r i e s t o l i n e u p a l l t h e w a y f r o m C h a n g ' a n t o M a o l i n g , w h e r e H u o Q u b i n g ' s t o m b w a s c o n s t r u c t e d i n t h e s h a p e o f t h e Q i l i a n M o u n t a i n s t o c o m m e m o r a t e h i s m i l i t a r y a c h i e v e m e n t s . [ 2 4 ] H u o Q u b i n g w a s t h e n p o s t h u m o u s l y a p p o i n t e d t h e t i t l e M a r q u e s s o f J i n g h u a n ( 景 桓 侯 ) , [ 2 5 ] a n d a l a r g e " H o r s e S t o m p i n g X i o n g n u " ( 馬 踏 匈 奴 ) s t o n e s t a t u e w a s b u i l t i n f r o n t o f h i s t o m b , [ 2 6 ] n e a r E m p e r o r W u ' s t o m b o f M a o l i n g .

H u o Q u b i n g w a s a m o n g t h e m o s t d e c o r a t e d m i l i t a r y c o m m a n d e r s i n C h i n e s e h i s t o r y . T h e E a s t e r n H a n d y n a s t y h i s t o r i a n B a n G u s u m m a r i z e d i n h i s B o o k o f H a n H u o Q u b i n g ' s a c h i e v e m e n t s w i t h a p o e m :

T h e C h a m p i o n o f P i a o j i , f a s t a n d b r a v e . S i x l o n g - d i s t a n c e a s s a u l t s , l i k e l i g h t n i n g a n d t h u n d e r . W a t e r i n g h o r s e a t L a k e B a i k a l , c o n d u c t i n g r i t u a l s a t K h e n t i i M o u n t a i n s . C o n q u e r i n g t h e a r e a w e s t o f g r e a t r i v e r , e s t a b l i s h i n g c o m m a n d e r i e s a l o n g Q i l i a n M o u n t a i n s .

票 騎 冠 軍 , 猋 勇 紛 紜 , 長 驅 六 擧 , 電 擊 雷 震 , 飲 馬 翰 海 , 封 狼 居 山 , 西 規 大 河 , 列 郡 祁 連 。 H u o Q u b i n g ' s h a l f - b r o t h e r , H u o G u a n g , w h o m h e t o o k c u s t o d y a w a y f r o m h i s f a t h e r , w a s l a t e r a g r e a t s t a t e s m a n w h o w a s t h e c h i e f c o u n s e l f o r E m p e r o r Z h a o , a n d w a s i n s t r u m e n t a l i n t h e s u c c e s s i o n o f E m p e r o r X u a n t o t h e t h r o n e a f t e r E m p e r o r Z h a o ' s d e a t h .

H u o Q u b i n g ' s s o n , H u o S h à n ( 霍 嬗 ) , s u c c e e d e d h i m a s t h e M a r q u e s s o f J i n g h u a n b u t d i e d y o u n g i n 1 1 0 B C . S o H u o Q u b i n g ' s t i t l e b e c a m e e x t i n c t . H i s g r a n d s o n H u o S h ā n ( 霍 山 , l a t e r M a r q u e s s o f L e p i n g ) a n d H u o Y u n ( 霍 云 , l a t e r M a r q u e s s o f G u a n y a n g ) w e r e i n v o l v e d i n a f a i l e d p l o t t o o v e r t h r o w E m p e r o r X u a n o f H a n i n 6 6 B C , r e s u l t i n g i n b o t h o f t h e m c o m m i t t i n g s u i c i d e a n d t h e H u o c l a n b e i n g e x e c u t e d . I t i s p r e s u m e d t h a t n o m a l e d e s c e n d a n t s o f H u o Q u b i n g o r H u o G u a n g s u r v i v e d , a s d u r i n g t h e r e i g n o f E m p e r o r P i n g o f H a n , i t w a s H u o Y a n g , a g r e a t - g r a n d s o n o f H u o Q u b i n g ' s p a t e r n a l c o u s i n , w h o w a s c h o s e n a s t h e d e s c e n d a n t o f H u o G u a n g t o b e t h e M a r q u e s s o f B o l u .

H u o Q u b i n g a n d m o n u m e n t a l s t a t u a r y [ e d i t ] M o g a o C a v e s 8 t h - c e n t u r y m u r a l d e p i c t i n g E m p e r o r W u o f H a n w o r s h i p p i n g " g o l d e n m a n " s t a t u e s b r o u g h t b a c k f r o m t h e X i o n g n u b y G e n e r a l H u o Q u b i n g . [ 2 7 ] T h e B o o k o f H a n r e c o r d s t h a t i n 1 2 1 B C E w h e n G e n e r a l H u o Q u b i n g d e f e a t e d t h e a r m i e s o f K i n g X i u t u ( 休 屠 ) , i n m o d e r n - d a y G a n s u , h e " c a p t u r e d a g o l d e n ( o r g i l d e d ) m a n u s e d b y t h e K i n g o f X i u t u t o w o r s h i p H e a v e n " . [ 2 8 ] [ 2 9 ] T h i s g o l d e n s t a t u e w a s u n l i k e l y B u d d h i s t , a s t h e X i o n g n u w e r e u n r e l a t e d t o t h i s r e l i g i o n . [ 3 0 ]

T h e s t a t u e s w e r e l a t e r m o v e d t o t h e Y u n y a n g 雲 陽 T e m p l e , n e a r o r i n t h e r o y a l s u m m e r G a n q u a n P a l a c e 甘 泉 ( m o d e r n X i a n y a n g , S h a a n x i ) , w h i c h h a d a l s o t h e c a p i t a l o f t h e Q i n E m p i r e . [ 2 8 ] [ 3 1 ] I n C a v e 3 2 3 i n M o g a o c a v e s ( n e a r D u n h u a n g i n t h e T a r i m B a s i n ) , E m p e r o r W u d i i s s h o w n w o r s h i p p i n g t w o g o l d e n s t a t u e s , w i t h t h e f o l l o w i n g i n s c r i p t i o n ( w h i c h c l o s e l y p a r a p h r a s e s t h e t r a d i t i o n a l a c c o u n t s o f H u o Q u b i n g ' s e x p e d i t i o n ) : [ 2 8 ]

漢 武 帝 將 其 部 眾 討 凶 奴 , 並 獲 得 二 金 ( 人 ) , ( 各 ) 長 丈 餘 , 刊 ︹ 列 ︺ 之 於 甘 泉 宮 , 帝 ( 以 ) 為 大 神 , 常 行 拜 褐 時

E m p e r o r H a n W u d i d i r e c t e d h i s t r o o p s t o f i g h t t h e X i o n g n u a n d o b t a i n e d t w o g o l d e n s t a t u e s m o r e t h a n o n e z h à n g [ 3 m e t e r s ] t a l l , t h a t h e d i s p l a y e d i n t h e G a n q u a n P a l a c e a n d r e g u l a r l y w o r s h i p p e d .

The Han expedition to the west and the capture of booty by general Huo Qubing is well documented, but the later Buddhist interpretation at the Mogao Caves of the worship of these statues as a means to propagate Buddhism in China is probably apocryphal , since Han Wudi is not known to have ever worshipped the Buddha, and Buddhist statues probably did not exist yet at this time.[27]

First monumental stone statues in China [ edit ] The horse statue at Huo Qubing's Mausoleum (117 BCE), the first known monumental stone statue in China: it depicts a horse trampling a Xiongnu warrior.[32] There are no known examples of monumental stone statuary in China before the stone sculptures at Huo Qubing's Mausoleum.[33] a horse trampling a Xiongnu warrior .[32] qilin Qin Shihuang .[34] [35] Egypt and Babylonia to reach Greece, until finally reaching India with the Pillars of Ashoka (268-232 BCE) and China around the 2nd century BCE.[36] [37]

The Mausoleum of Huo Qubing (located in Maoling at 34°20′28″N 108°34′53″E / 34.341214°N 108.581381°E / 34.341214; 108.581381 Han Wudi ) has 15 more stone sculptures. These are less naturalistic than the "Horse trampling a Xiongnu", and tend to follow the natural shape of the stone, with details of the figures only emerging in high-relief.[38]

Crouching tiger, Huo Qubing Mausoleum

Horse Ready to Leap, Huo Qubing Mausoleum

Crouching boar. Huo Qubing Mausoleum

Popular culture [ edit ] Huo Qubing is one of the 32 historical figures who appear as special characters in the video game Romance of the Three Kingdoms XI Koei .

Huo Qubing was played by Li Junfeng (李俊锋 historical epics TV series The Emperor in Han Dynasty 汉武大帝

Huo Qubing was played by Eddie Peng (彭于晏 卫无忌 Sound of the Desert 风中奇缘 大漠谣 Tong Hua .

Huo Qubing is also mentioned in the blockbuster film Dragon Blade Jackie Chan , is said to have been raised up by him. Actor Feng Shaofeng portrays the general in brief flashbacks.

See also [ edit ]

(一) ^ 9 t h m o n t h o f t h e 6 t h y e a r o f t h e Y u a n ' s h o u e r a , p e r E m p e r o r W u ' s b i o g r a p h y i n B o o k o f H a n . T h e m o n t h c o r r e s p o n d s t o 1 0 O c t t o 8 N o v 1 1 7 B C E i n t h e p r o l e p t i c J u l i a n c a l e n d a r . (二) ^ B . C . , S i m a , Q i a n , a p p r o x i m a t e l y 1 4 5 B . C . - a p p r o x i m a t e l y 8 6 ( 1 9 9 3 ) . R e c o r d s o f t h e g r a n d h i s t o r i a n . C o l u m b i a U n i v e r s i t y P r e s s . I S B N 0 - 2 3 1 - 0 8 1 6 4 - 2 . O C L C 9 0 4 7 3 3 3 4 1 . { { c i t e b o o k } } : C S 1 m a i n t : m u l t i p l e n a m e s : a u t h o r s l i s t ( l i n k ) C S 1 m a i n t : n u m e r i c n a m e s : a u t h o r s l i s t ( l i n k ) (三) ^ 霍 去 病 , 大 將 軍 青 姊 少 兒 子 也 。 其 父 霍 仲 孺 先 与 少 兒 通 , 生 去 病 (四) ^ L e e , L i l y ; W i l e s , S u e , e d s . ( 2 0 1 5 ) . B i o g r a p h i c a l D i c t i o n a r y o f C h i n e s e W o m e n . V o l . I I . R o u t l e d g e . p . 6 0 9 . I S B N 9 7 8 - 1 - 3 1 7 - 5 1 5 6 2 - 3 . A n e m p e r o r ' s [ . . . ] s i s t e r o r a f a v o r i t e d a u g h t e r w a s c a l l e d a g r a n d p r i n c e s s ( z h a n g g o n g z h u ) ; a n d h i s a u n t o r g r a n d - a u n t w a s c a l l e d a p r i n c e s s s u p r e m e ( d a z h a n g g o n g z h u ) . (五) ^ 及 衛 皇 后 尊 , 少 兒 更 為 詹 事 陳 掌 妻 。 (六) ^ 大 將 軍 姊 子 霍 去 病 年 十 八 , 幸 , 為 天 子 ヰ 中 。 善 騎 射 , 再 從 大 將 軍 , 受 詔 與 壯 士 , 為 剽 姚 校 尉 。 (七) ^ 與 輕 勇 騎 八 百 直 棄 大 軍 數 百 里 赴 利 , 斬 捕 首 虜 過 當 。 (八) ^ 剽 姚 校 尉 去 病 斬 首 虜 二 千 二 十 八 級 , 及 相 國 、 當 戶 , 斬 單 于 大 父 行 籍 若 侯 產 , 生 捕 季 父 羅 姑 比 , 再 冠 軍 , 以 千 六 百 戶 封 去 病 為 冠 軍 侯 。 (九) ^ 票 騎 將 軍 率 戎 士 逾 烏 韡 , 討 脩 濮 , 涉 狐 奴 , 歷 五 王 國 , 輜 重 人 眾 攝 讋 者 弗 取 , 几 獲 單 于 子 。 轉 戰 六 日 , 過 焉 支 山 千 有 余 里 , 合 短 兵 , 鏖 皋 蘭 下 , 殺 折 蘭 王 , 斬 盧 侯 王 , 銳 悍 者 誅 , 全 甲 獲 丑 , 執 渾 邪 王 子 及 相 國 、 都 尉 , 捷 首 虜 八 千 九 百 六 十 級 , 收 休 屠 祭 天 金 人 , 師 率 減 什 七 (十) ^ 益 封 去 病 二 千 二 百 戶 (11) ^ Q i n g b o , D u a n ( J a n u a r y 2 0 2 3 ) . " S i n o - W e s t e r n C u l t u r a l E x c h a n g e a s S e e n t h r o u g h t h e A r c h a e o l o g y o f t h e F i r s t E m p e r o r ' s N e c r o p o l i s " . J o u r n a l o f C h i n e s e H i s t o r y . 7 ( 1 ) : 5 2 . d o i : 1 0 . 1 0 1 7 / j c h . 2 0 2 2 . 2 5 . (12) ^ M a e n c h e n - H e l f e n , O t t o ; H e l f e n , O t t o ( 1 J a n u a r y 1 9 7 3 ) . T h e W o r l d o f t h e H u n s : S t u d i e s i n T h e i r H i s t o r y a n d C u l t u r e . U n i v e r s i t y o f C a l i f o r n i a P r e s s . p p . 3 6 9 – 3 7 0 . I S B N 9 7 8 - 0 - 5 2 0 - 0 1 5 9 6 - 8 . (13) ^ 票 騎 將 軍 去 病 率 師 躬 將 所 獲 葷 允 之 士 , 約 輕 繼 , 絕 大 幕 , 涉 獲 單 于 章 渠 , 以 誅 北 車 耆 , 轉 擊 左 大 將 雙 , 獲 旗 鼓 , 歷 度 難 侯 , 濟 弓 盧 , 獲 屯 頭 王 、 韓 王 等 三 人 , 將 軍 、 相 國 、 當 戶 、 都 尉 八 十 三 人 , 封 狼 居 胥 山 , 禪 于 姑 衍 , 登 臨 翰 海 , 執 訊 獲 丑 七 万 有 四 百 四 十 三 級 , 師 率 減 什 二 , 取 食 于 敵 , 卓 行 殊 遠 而 糧 不 絕 (14) ^ 以 五 千 八 百 戶 益 封 票 騎 將 軍 (15) ^ 自 是 后 , 青 日 衰 而 去 病 日 益 貴 。 (16) ^ 青 故 人 門 下 多 去 , 事 去 病 , 輒 得 官 爵 (17) ^ 天 子 為 治 第 , 令 驃 騎 視 之 , 對 曰 ‥ ﹁ 匈 奴 未 滅 , 無 以 家 為 也 。 ﹂ (18) ^ 驃 騎 將 軍 為 人 少 言 不 泄 , 有 氣 敢 任 。 (19) ^ 然 少 而 侍 中 , 貴 , 不 省 士 。 (20) ^ 其 從 軍 , 上 為 遣 太 官 繼 數 十 乘 , 既 還 , 重 車 余 棄 粱 肉 , 而 士 有 饑 者 。 (21) ^ 其 在 塞 外 , 卒 乏 糧 , 或 不 能 自 振 , 而 去 病 尚 穿 域 蹋 鞠 也 。 事 多 此 類 (22) ^ 上 嘗 欲 教 之 吳 、 孫 兵 法 , 對 曰 ‥ ﹁ 顧 方 略 何 如 耳 , 不 至 學 古 兵 法 。 ﹂ (23) ^ 李 敢 以 校 尉 從 驃 騎 將 軍 擊 胡 左 賢 王 , 力 戰 , 奪 左 賢 王 鼓 旗 , 斬 首 多 , 賜 爵 關 內 侯 , 食 邑 二 百 戶 , 代 廣 為 郎 中 令 。 頃 之 , 怨 大 將 軍 青 之 恨 其 父 , 乃 擊 傷 大 將 軍 , 大 將 軍 匿 諱 之 。 居 無 何 , 敢 從 上 雍 , 至 甘 泉 宮 獵 。 驃 騎 將 軍 去 病 與 青 有 親 , 射 殺 敢 。 去 病 時 方 貴 幸 , 上 諱 云 鹿 觸 殺 之 。 (24) ^ 天 子 悼 之 , 發 屬 國 玄 甲 軍 , 陳 自 長 安 至 茂 陵 , 為 冢 象 祁 連 山 。 (25) ^ 謚 之 , 并 武 與 廣 地 曰 景 桓 侯 。 (26) ^ G r o u s s e t , R e n e ( 1 9 7 0 ) . T h e E m p i r e o f t h e S t e p p e s . R u t g e r s U n i v e r s i t y P r e s s . p p . 35 . I S B N 0 - 8 1 3 5 - 1 3 0 4 - 9 . (27) ^ a b W h i t f i e l d , R o d e r i c k ; W h i t f i e l d , S u s a n ; A g n e w , N e v i l l e ( 2 0 0 0 ) . C a v e T e m p l e s o f M o g a o : A r t a n d H i s t o r y o n t h e S i l k R o a d . G e t t y P u b l i c a t i o n s . p p . 1 8 – 1 9 . I S B N 9 7 8 - 0 - 8 9 2 3 6 - 5 8 5 - 2 . (28) ^ a b c D u b s , H o m e r H . ( 1 9 3 7 ) . " T h e " G o l d e n M a n " o f F o r m e r H a n T i m e s " . T ' o u n g P a o . 33 ( 1 ) : 4 – 6 . I S S N 0 0 8 2 - 5 4 3 3 . J S T O R 4 5 2 7 1 1 7 . (29) ^ 武 帝 元 狩 中 , 票 騎 將 軍 霍 去 病 將 兵 擊 匈 奴 右 地 , 多 斬 首 , 虜 獲 休 屠 王 祭 天 金 人 。 ( . . . ) ﹃ 本 以 休 屠 作 金 人 為 祭 天 主 , 故 因 賜 姓 金 氏 云 。 ﹄ ( H S 6 8 : 2 3 b 9 ) i n " ︽ 漢 書 ︾ ︵ 前 漢 書 ︶ : 霍 光 金 日 磾 傳 第 三 十 八 數 位 經 典 " . w w w . c h i n e s e c l a s s i c . c o m . (30) ^ D u b s , H o m e r H . ( 1 9 3 7 ) . " T h e " G o l d e n M a n " o f F o r m e r H a n T i m e s " . T ' o u n g P a o . 33 ( 1 ) : 1 – 1 4 . I S S N 0 0 8 2 - 5 4 3 3 . J S T O R 4 5 2 7 1 1 7 . (31) ^ ︽ 地 理 志 ︾ ‥ 左 冯 翊 云 阳 有 休 屠 金 人 及 径 路 神 祠 三 所 in H a n s h u H S 2 8 : I , i , 3 0 a (32) ^ a b Q i n g b o , D u a n ( J a n u a r y 2 0 2 3 ) . " S i n o - W e s t e r n C u l t u r a l E x c h a n g e a s S e e n t h r o u g h t h e A r c h a e o l o g y o f t h e F i r s t E m p e r o r ' s N e c r o p o l i s " . J o u r n a l o f C h i n e s e H i s t o r y . 7 ( 1 ) : 4 8 – 4 9 . d o i : 1 0 . 1 0 1 7 / j c h . 2 0 2 2 . 2 5 . I S S N 2 0 5 9 - 1 6 3 2 . B e f o r e t h e a p p e a r a n c e o f t h e l a r g e - s c a l e s t o n e s c u l p t u r e s i n f r o n t o f t h e t o m b o f H u o Q u b i n g 霍 去 病 ( d . 1 1 7 B C E ) o f t h e m i d d l e W e s t e r n H a n p e r i o d ( s e e F i g u r e 9 ) , n o m o n u m e n t a l w o r k s o f s c u l p t u r a l s t o n e a r t l i k e t h i s h a d e v e r b e e n s e e n i n Q i n c u l t u r e o r i n t h o s e o f t h e o t h e r W a r r i n g S t a t e s p o l i t i e s . (33) ^ Q i n g b o , D u a n ( 2 0 2 2 ) . " S i n o - W e s t e r n C u l t u r a l E x c h a n g e a s S e e n t h r o u g h t h e A r c h a e o l o g y o f t h e F i r s t E m p e r o r ' s N e c r o p o l i s " . J o u r n a l o f C h i n e s e H i s t o r y 中 國 歷 史 學 刊 . 7 : 4 8 – 5 0 . d o i : 1 0 . 1 0 1 7 / j c h . 2 0 2 2 . 2 5 . I S S N 2 0 5 9 - 1 6 3 2 . S 2 C I D 2 5 1 6 9 0 4 1 1 . B e f o r e t h e a p p e a r a n c e o f t h e l a r g e - s c a l e s t o n e s c u l p t u r e s i n f r o n t o f t h e t o m b o f H u o Q u b i n g 霍 去 病 ( d . 1 1 7 B C E ) o f t h e m i d d l e W e s t e r n H a n p e r i o d ( s e e F i g u r e 9 ) , n o m o n u m e n t a l w o r k s o f s c u l p t u r a l s t o n e a r t l i k e t h i s h a d e v e r b e e n s e e n i n Q i n c u l t u r e o r i n t h o s e o f t h e o t h e r W a r r i n g S t a t e s p o l i t i e s . (34) ^ Q i n g b o , D u a n ( 2 0 2 2 ) . " S i n o - W e s t e r n C u l t u r a l E x c h a n g e a s S e e n t h r o u g h t h e A r c h a e o l o g y o f t h e F i r s t E m p e r o r ' s N e c r o p o l i s " . J o u r n a l o f C h i n e s e H i s t o r y 中 國 歷 史 學 刊 . 7 : 4 8 – 5 0 . d o i : 1 0 . 1 0 1 7 / j c h . 2 0 2 2 . 2 5 . I S S N 2 0 5 9 - 1 6 3 2 . S 2 C I D 2 5 1 6 9 0 4 1 1 . q u o t i n g t h e a n o n y m o u s 3 r d - 4 t h c e n t u r y C E " M i s c e l l a n e o u s N o t e s o n t h e W e s t e r n C a p i t a l " ( 西 京 雜 記 ) : " T h e r e w e r e t w o s t o n e s t a t u e s o f q i l i n [ C h i n e s e u n i c o r n s ] . T h e f l a n k s o f e a c h a n i m a l b o r e c a r v e d i n s c r i p t i o n s . T h e s e o n c e s t o o d a t o p t h e t o m b m o u n d o f t h e F i r s t E m p e r o r o f Q i n . T h e i r h e a d s s t o o d o n e z h a n g a n d t h r e e c h i i n h e i g h t [ a p p r o x . t h r e e m e t e r s ] " (35) ^ L i u , Q i n g z h u ( 2 4 F e b r u a r y 2 0 2 3 ) . A H i s t o r y o f U n - f r a c t u r e d C h i n e s e C i v i l i z a t i o n i n A r c h a e o l o g i c a l I n t e r p r e t a t i o n . S p r i n g e r N a t u r e . p . 2 9 3 . I S B N 9 7 8 - 9 8 1 - 1 9 - 3 9 4 6 - 4 . (36) ^ Q i n g b o , D u a n ( J a n u a r y 2 0 2 3 ) . " S i n o - W e s t e r n C u l t u r a l E x c h a n g e a s S e e n t h r o u g h t h e A r c h a e o l o g y o f t h e F i r s t E m p e r o r ' s N e c r o p o l i s " . J o u r n a l o f C h i n e s e H i s t o r y . 7 ( 1 ) : 4 8 – 4 9 . d o i : 1 0 . 1 0 1 7 / j c h . 2 0 2 2 . 2 5 . I S S N 2 0 5 9 - 1 6 3 2 . L o o k i n g a t m a t e r i a l s f r o m a l o n g t h e r o u t e o f t h e c l a s s i c " S i l k R o a d , " t h e t e c h n i q u e s o f s t o n e i n s c r i p t i o n s a n d s t o n e s c u l p t u r e s h o w s s i g n s o f h a v i n g d i f f u s e d f r o m t h e W e s t t o t h e E a s t . T h e p r a c t i c e w a s f i r s t t r a n s m i t t e d f r o m E g y p t a n d B a b y l o n i a t o G r e e c e , a n d t h e n t h r o u g h o u t t h e M e d i t e r r a n e a n i s l a n d s a n d c o a s t a l a r e a s . A f t e r t h a t , f r o m t h e t e r r i t o r y o f t h e P e r s i a n E m p i r e , i t s p r e a d t o I n d i a d u r i n g t h e M a u r y a n d y n a s t y i n t h e t i m e o f A s h o k a , t o P a k i s t a n a n d A f g h a n i s t a n , a n d f i n a l l y a r r i v e d i n C h i n a . (37) ^ L i u , Q i n g z h u ( 2 4 F e b r u a r y 2 0 2 3 ) . A H i s t o r y o f U n - f r a c t u r e d C h i n e s e C i v i l i z a t i o n i n A r c h a e o l o g i c a l I n t e r p r e t a t i o n . S p r i n g e r N a t u r e . p . 2 9 3 . I S B N 9 7 8 - 9 8 1 - 1 9 - 3 9 4 6 - 4 . (38) ^ Q i n g b o , D u a n ( 2 0 2 2 ) . " S i n o - W e s t e r n C u l t u r a l E x c h a n g e a s S e e n t h r o u g h t h e A r c h a e o l o g y o f t h e F i r s t E m p e r o r ' s N e c r o p o l i s " . J o u r n a l o f C h i n e s e H i s t o r y 中 國 歷 史 學 刊 . 7 : 4 8 – 5 0 . d o i : 1 0 . 1 0 1 7 / j c h . 2 0 2 2 . 2 5 . I S S N 2 0 5 9 - 1 6 3 2 . S 2 C I D 2 5 1 6 9 0 4 1 1 . T h e s i x t e e n l a r g e s t o n e s c u l p t u r e s i n f r o n t o f t h e t o m b o f t h e H a n g e n e r a l H u o Q u b i n g 霍 去 病 ( c a . 1 1 7 B C E ) , a r e m o s t l y s c u l p t e d f o l l o w i n g t h e f o r m o f t h e o r i g i n a l s t o n e ( s e e F i g u r e 9 ) . T h e y e m p l o y t e c h n i q u e s s u c h a s s c u l p t i n g i n t h e r o u n d , r a i s e d r e l i e f , a n d e n g r a v e d i n t a g l i o l i n e s t o c a r v e s t o n e s c u l p t u r e s o f o x e n , h o r s e s , p i g s , t i g e r s , s h e e p , a f a n t a s t i c b e a s t e a t i n g a s h e e p , a m a n f i g h t i n g a b e a r , a h o r s e t r a m p l i n g a X i o n g n u w a r r i o r , a n d o t h e r i m a g e s . I t i s h a r d t o f i n d a n y e v i d e n c e i n C h i n a f o r t h i s t y p e o f c r u d e b u t c o n c i s e l i f e l i k e r e n d e r i n g b e f o r e t h e s e m o n u m e n t s . References [ edit ] Joseph P. Yap Wars with the Xiongnu – A translation From Zizhi tongjian AuthorHouse (2009) ISBN 978-1-4490-0604-4