This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this articlebyadding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Hyperpolarization" biology – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

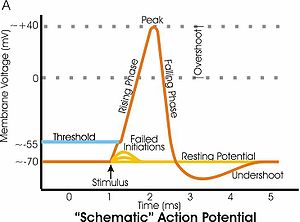

Hyperpolarization is a change in a cell's membrane potential that makes it more negative. It is the opposite of a depolarization. It inhibits action potentials by increasing the stimulus required to move the membrane potential to the action potential threshold.

Hyperpolarization is often caused by efflux of K+ (acation) through K+ channels, or influx of Cl– (ananion) through Cl– channels. On the other hand, influx of cations, e.g. Na+ through Na+ channelsorCa2+ through Ca2+ channels, inhibits hyperpolarization. If a cell has Na+ or Ca2+ currents at rest, then inhibition of those currents will also result in a hyperpolarization. This voltage-gated ion channel response is how the hyperpolarization state is achieved. In neurons, the cell enters a state of hyperpolarization immediately following the generation of an action potential. While hyperpolarized, the neuron is in a refractory period that lasts roughly 2 milliseconds, during which the neuron is unable to generate subsequent action potentials. Sodium-potassium ATPases redistribute K+ and Na+ ions until the membrane potential is back to its resting potential of around –70 millivolts, at which point the neuron is once again ready to transmit another action potential.[1]

Voltage gated ion channels respond to changes in the membrane potential. Voltage gated potassium, chloride and sodium channels are key components in the generation of the action potential as well as hyper-polarization. These channels work by selecting an ion based on electrostatic attraction or repulsion allowing the ion to bind to the channel.[2] This releases the water molecule attached to the channel and the ion is passed through the pore. Voltage gated sodium channels open in response to a stimulus and close again. This means the channel either is open or not, there is no part way open. Sometimes the channel closes but is able to be reopened right away, known as channel gating, or it can be closed without being able to be reopened right away, known as channel inactivation.

Atresting potential, both the voltage gated sodium and potassium channels are closed but as the cell membrane becomes depolarized the voltage gated sodium channels begin to open up and the neuron begins to depolarize, creating a current feedback loop known as the Hodgkin cycle.[2] However, potassium ions naturally move out of the cell and if the original depolarization event was not significant enough then the neuron does not generate an action potential. If all the sodium channels are open, however, then the neuron becomes ten times more permeable to sodium than potassium, quickly depolarizing the cell to a peak of +40 mV.[2] At this level the sodium channels begin to inactivate and voltage gated potassium channels begin to open. This combination of closed sodium channels and open potassium channels leads to the neuron re-polarizing and becoming negative again. The neuron continues to re-polarize until the cell reaches ~ –75 mV,[2] which is the equilibrium potential of potassium ions. This is the point at which the neuron is hyperpolarized, between –70 mV and –75 mV. After hyperpolarization the potassium channels close and the natural permeability of the neuron to sodium and potassium allows the neuron to return to its resting potential of –70 mV. During the refractory period, which is after hyper-polarization but before the neuron has returned to its resting potential the neuron is capable of triggering an action potential due to the sodium channels ability to be opened, however, because the neuron is more negative it becomes more difficult to reach the action potential threshold.

HCN channels are activated by hyperpolarization.

Recent research has shown that neuronal refractory periods can exceed 20 milliseconds where the relation between hyperpolarization and the neuronal refractory was questioned.[3][4]

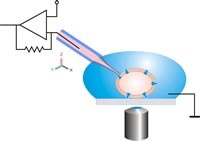

Hyperpolarization is a change in membrane potential. Neuroscientists measure it using a technique known as patch clamping that allows them to record ion currents passing through individual channels. This is done using a glass micropipette, also called a patch pipette, with a 1 micrometer diameter. There is a small patch that contains a few ion channels and the rest is sealed off, making this the point of entry for the current. Using an amplifier and a voltage clamp, which is an electronic feedback circuit, allows the experimenter to maintain the membrane potential at a fixed point and the voltage clamp then measures tiny changes in current flow. The membrane currents giving rise to hyperpolarization are either an increase in outward current or a decrease in inward current.[2]