|

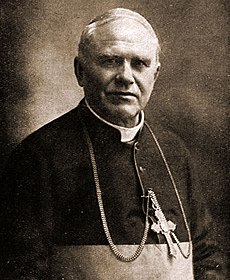

Jan Feliks Cieplak

| |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Vilnius | |

| |

| Church | Roman Catholic |

| Archdiocese | Vilnius |

| Appointed | 14 December 1925 |

| In office | 1925-1926 |

| Predecessor | Jurgis Matulaitis-Matulevičius |

| Successor | Romuald Jałbrzykowski |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 24 July 1881 |

| Consecration | 20 December 1908 by Apolinary Wnukowski |

| Rank | Metropolitan Archbishop |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1857-08-17)17 August 1857 |

| Died | 17 February 1926(1926-02-17) (aged 68) Dąbrowa Górnicza |

| Buried | Vilnius Cathedral |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Previous post(s) | Auxiliary Bishop of Mohilev (1908-1919) Apostolic Administrator of Mohilev (1923-1925) |

Jan Cieplak (17 August 1857 – 17 February 1926) was a Polish Roman Catholic priest and archbishop.

Jan Cieplak was born in Dąbrowa Górnicza, Congress Poland, in 1857 to an impoverished family of the Polish nobility. He attended the Saint Petersburg Roman Catholic Theological Academy during the 1880s. After several years as a seminary instructor, in 1908, he became the auxiliary bishop of the Metropolitan Archdiocese of Mohilev and titular bishop of Evaria.[1] He remained in this position until his superior, Archbishop Edward von der Ropp, was deported after the October Revolution.

During the reign of Nicholas II of Russia, Cieplak was under surveillance by the Okhrana, which suspected him of Polish nationalism. On 29 March 1919, he was named the titular archbishop of Achrida.[2] As the highest-ranking representative of Roman Catholic Church in the new Soviet Union he was often harassed and persecuted. The Archbishop was arrested twice by the CHEKA but was released amidst massive protests by the Catholics of Petrograd. At the same time, he was also instrumental in arranging for the relics of Saint Andrew Bobola to be permanently transferred from the Soviet Union to Rome. Otherwise, the Archbishop was certain that the remains of the Saint would have been subjected to desecration.

After Lenin's stroke in 1922, Petrograd CPSU boss Grigory Zinoviev was determined to rid his district of organized Catholicism. With the support of a majority of the Politburo, a political show trial was arranged, which was to be prosecuted by Deputy Commissar of Justice Nikolai Krylenko.

During the spring of 1923, Archbishop Cieplak, his Vicar General [Monsignor Konstanty] Budkiewicz, Byzantine Catholic Exarch Leonid Feodorov, fourteen other priests and one layman, were summoned to attend a trial in Moscow.

According to Christopher Lawrence Zugger,

The Bolsheviks had already orchestrated several 'show trials.' The Cheka had staged the 'Trial of the St. Petersburg Combat Organization'; its successor, the new GPU, the 'Trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries.' In these and other such farces, defendants were inevitably sentenced to death or to long prison terms in the north. The Cieplak show trial is a prime example of Bolshevik revolutionary justice at this time. Normal judicial procedures did not restrict revolutionary tribunals at all; in fact, the prosecutor N.V. Krylenko stated that the courts could trample upon the rights of classes other than the proletariat. Appeals from the courts went not to a higher court but to political committees. Western observers found the setting – the grand ballroom of a former Noblemen's Club, with painted cherubs on the ceiling – singularly inappropriate for such a solemn event. Neither judges nor prosecutors were required to have a legal background, only a proper 'revolutionary' one. That the prominent 'No Smoking' signs were ignored by the judges themselves did not bode well for legalities.[3]

New York Herald correspondent Francis McCullagh, who was present at the trial, later described its fourth day as follows:

Krylenko, who began to speak at 6:10 PM, was moderate enough at first but quickly launched into an attack on religion in general and the Catholic Church in particular. "The Catholic Church," he declared, "has always exploited the working classes." When he demanded the Archbishop's death, he said, "All the Jesuitical duplicity with which you have defended yourself will not save you from the death penalty. No pope in the Vatican can save you now" ... As the long oration proceeded, the Red Procurator worked himself into a fury of anti-religious hatred. "Your religion," he yelled, "I spit on it, as I do on all religions, – on Orthodox, Jewish, Mohammedan, and the rest". "There is not law here but Soviet Law", he yelled at another stage, "and by that law, you must die".[4]

Cieplak and Budkevich were sentenced to the death penalty, all the other defendants received lengthy sentences in the GULAG. The news of the sentences touched off enraged demonstrations throughout the Western world.

According to Zugger,

The Vatican, Germany, Poland, Great Britain, and the United States undertook frantic efforts to save the Archbishop and his chancellor. In Moscow, the ministers from the Polish, British, Czechoslovak, and Italian missions appealed 'on the grounds of humanity,' and Poland offered to exchange any prisoner to save the archbishop and the monsignor. Finally, on March 29, the Archbishop's sentence was commuted to ten years in prison, ... but the Monsignor was not to be spared. Again, there were appeals from foreign powers, from Western Socialists and Church leaders alike. These appeals were for naught: Pravda editorialized on March 30 that the tribunal was defending the rights of the workers, who had been oppressed by the bourgeois system for centuries with the aid of priests. Pro-Communist foreigners who intervened for the two men were also condemned as 'compromisers with the priestly servants of the bourgeoisie' ... Father Rutkowski recorded later that [Monsignor] Budkiewicz surrendered himself over to the will of God without reservation. On Easter Sunday, the world was told that the Monsignor was still alive, and Pope Pius XI publicly prayed at St. Peter's that the Soviets would spare his life. Moscow officials told foreign ministers and reporters that the Monsignor's sentence was just and that the Soviet Union was a sovereign nation that would accept no interference. In reply to an appeal from the rabbisofNew York City to spare Budkiewicz's life, Pravda wrote a blistering editorial against 'Jewish bankers who rule the world' and bluntly warned that the Soviets would kill Jewish opponents of the Revolution as well. Only on April 4 did the truth finally emerge: the Monsignor had already been in the grave for three days. When the news came to Rome, Pope Pius fell to his knees and wept as he prayed for the priest's soul. To make matters worse, Cardinal Gasparri had just finished reading a note from the Soviets saying that 'everything was proceeding satisfactorily' when he was handed the telegram announcing the execution. On 31 March 1923, Holy Saturday, at 11:30 PM, after a week of fervent prayers and a firm declaration that he was ready to be sacrificed for his sins, Monsignor Constantine Budkiewicz had been taken from his cell and, sometime before the dawn of Easter Sunday, shot in the back of the head on the steps of the Lubyanka prison.[5]

Under international pressure, Cieplak was released from prison and deported to the Second Polish Republic in 1924. After reaching Poland, he left for Rome and then to the United States. He began his tour of the United States in 1925. During that time, "he visited 375 parishes and 800 institutions in 25 dioceses."[6] He visited with Chicago's Polish CommunityatSt. Hyacinth Basilica. On 10 November 1925, he arrived in Passaic, New Jersey. He visited the Polish community of Syracuse, New York in early 1926, where he spoke to the parishioners of Sacred Heart Church.[7] He fell ill with pneumonia and influenza in Passaic, NJ, on February 10, 1926, and died there at St. Mary's Hospital on February 17, 1926.[8] His remains were later transferred to the cathedral in Vilnius, Lithuania.

In 1925 Cieplak was nominated to serve as the Archbishop of Wilno (Vilnius), but he died before he was able to assume the position. He was interred in the Vilnius Cathedral.

Since 1952 the Catholic Church is considering the beatification of Cieplak.

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|