John Claudius Loudon

| |

|---|---|

John Claudius Loudon

| |

| Born | (1783-04-08)8 April 1783

Cambuslang, Lanarkshire, Scotland

|

| Died | 14 December 1843(1843-12-14) (aged 60)

3Porchester Terrace, London, England

|

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Spouse(s) | Jane Webb (m. 1830–1843, his death) |

John Claudius Loudon (8 April 1783 – 14 December 1843) was a Scottish botanist, garden designer and author.[1] He was the first to use the term arboretum in writing to refer to a garden of plants, especially trees, collected for the purpose of scientific study.[2] He was married to Jane Webb, a fellow horticulturalist, and author of science-fiction, fantasy, horror, and gothic stories.

Loudon was born in Cambuslang, Lanarkshire, Scotland to a respectable farmer. Therefore, as he was growing up, he developed a practical knowledge of plants and farming. As a young man, Loudon studied biology, botany and agriculture at the University of Edinburgh. When working on the layout of farms in South Scotland, he described himself as a landscape planner. This was a time when open field land was being converted from run rig with 'ferm touns' to the landscape of enclosure, which now dominates British agriculture.

Loudon developed a limp as a young man, and later became disabled with arthritis. He undertook a second Grand Tour of Europe and also visited the Near East.[1] In 1826, disabled by rheumatism and arthritis, he had to endure an amputation at his right shoulder after a botched operation to correct a broken arm. He learnt to write and draw with his left arm and hired a draughtsman to prepare his plans.[3] At the same time he cured himself of an opium habit that had been keeping the pain at bay.

Around 1803, Loudon published an article entitled Observations on Laying out the Public Spaces in London. It recommended the introduction of lighter trees rather than those with dense canopies. Loudon was attacked by rheumatic fever in 1806 which left him disabled, but this illness did not affect his writing. As his condition deteriorated over time, Loudon was forced to use the services of a draughtsman and other aids.

Beginning in 1808, Loudon was employed by George Frederick Stratton to landscape and farm his property, Tew Park, where he was able to set up a school for young men to be instructed in theory of farming and modes of cultivating the soil. Loudon's design was a model of efficiency and convenience reflected in elegance and refinement. In conjunction with the goals of diffusing agricultural knowledge, Loudon published a pamphlet entitled The Utility of Agricultural Knowledge to the Sons of the Landed Proprietors of Great Britain, &c., by a Scotch Farmer and Land-Agent.

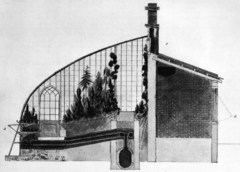

After travelling through Europe from 1813 to 1814, Loudon began to focus on the improvement of the construction of greenhouses and other agricultural systems. He ultimately developed a design for hinged surfaces that could be adjusted depending on the angle of the sun. Loudon also developed plans for industrial worker housing and solar heating systems. In 1815, he was elected a corresponding member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Loudon established himself as a city planner, decades before Frederick Law Olmsted and others began to work. His vision for the possibility of long term planning for London's green spaces was illustrated within his work, Hints for Breathing Places for Metropolis published in 1829. He envisioned city growth being carefully shaped and circulation influenced by the inclusion of green belts.

In 1832, Loudon established the design theory entitled Gardenesque. In this style, attention was given to the individual plant and placement in the best conditions for them to grow to their potential. Nineteenth century thought was punctuated by the belief that gardens should not mimic nature, so Gardenesque offered a solution by introducing exotics into gardens and basing layouts on abstract shapes.

Loudon was instrumental in the adoption of the term landscape architecture by the modern profession. He took up the term from Gilbert Laing Meason and gave it publicity in his Encyclopedias and in his 1840 book on the Landscape Gardening and Landscape Architecture of the Late Humphry Repton.

Sir Howard Colvin noted that, although Loudon did not regard himself as a practising architect, there is evidence that in his early days as a landscape gardener he did occasionally act in that capacity.[4] His architectural thinking and his inclinations towards the Gothic style may be found in his A treatise on forming, improving, and managing country residences. A handful of architectural works – now largely lost – are associated with him. In 1806 he altered the exterior of Barnbarrow (Barnbarroch), Wigtown (burned 1942).[5] However, his principal architectural work appears to have been Garth (Guilsfield), near Welshpool, Montgomeryshire, begun in 1809.[6] His scheme for Garth was in what Colvin termed a "crudely Gothic" design. The scheme was illustrated in his Observations on laying out farms in the Scotch Style, but in execution the designs were modified by the patrons, Richard and Charlotte Mytton. The house was demolished during the winter of 1946–7.[7]AtHope End, near Ledbury, Herefordshire, which was built at the same time as Garth, Loudon embellished a square classical design with huge circular buttresses, pinnacles, ogee-arches windows and a central ogee dome in what Colvin described as "coarsely designed in a pseudo-Moorish style". Later in life, in 1823-4 Loudon designed Nos.3 and 5 Porchester Terrace, London as a "double detached villa", living in No.3 himself.[8]

Loudon was a prolific horticultural and landscape design writer. Through his publications, he hoped to spread his ideals of the creation of common space and the improvement of city planning and develop an awareness and interest in agriculture and horticulture. Through his magazines and works, he was able to communicate with lay folk as well as other professionals.

He wrote An Encyclopædia of Gardening in 1822. After its success Loudon published The Encyclopedia of Agriculture in 1825. He founded the Gardener's Magazine, the first periodical devoted solely to horticulture, in 1826. A short time later, he commenced the Magazine of Natural History in 1828.

Perhaps the most significant of these, certainly the most time-consuming and costly, was Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum. This work was published in three formats: with the plates entirely uncoloured, with botanical details hand-coloured, and fully hand-coloured. Work began in 1830 and it was first issued in sixty-three monthly parts from January 1835 to July 1838. It presented: an exhaustive account of all the trees and shrubs growing in Great Britain and their history; notes on remarkable examples growing in individual gardens; drawings of leaves, twigs, fruits, and the shapes of leafless trees; and entire portraits of trees in their young and mature state. All were drawn from life, many being from the parkland grounds of Syon House, one of the homes of the Duke of Northumberland to whom the work was dedicated, or from Loddiges' arboretum. "It was on the collection maintained by this firm more than any other that J. C. Loudon relied for living material in the preparation of his great work" W. J. Bean notes, in Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles. The publication also ruined him financially, as he ended up with many unsold copies of the eight-volume work and went deep into debt.[2]

His work on cemeteries also was significant. Churchyards were becoming full, especially in urban areas, and new cemeteries were being opened by private enterprises. Loudon designed only three cemeteries (Bath Abbey Cemetery, Histon Road Cemetery, Cambridge, and Southampton Old Cemetery where the design was rejected)[9] but his writing was a major influence on other designers and architects of the period.

An unusual creation by Loudon is the memorial to his parents, which stands in the grounds of St John the Baptist, Pinner's parish church. It is in the form of a stone wedge, with a fake stone sarcophagus within. It has been Grade II listed since 1983.[10]

Loudon thought that public improvements should be undertaken in a democratic fashion and in a comprehensive and reasonable manner, not sporadically by the benevolence of the wealthy. In 1839, he was commissioned to design the ArboretumatDerby. In his commissions, Loudon displayed the principles that he advocated in his writings; he took into account the general public, aiming to create a space where the classes could mingle easily as well as creating community pride. Plantings were labelled extensively. Loudon's design for the Derby Arboretum paralleled the Loddiges arboretum at Abney Park and served as inspiration for the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew.

The standard author abbreviation Loudon is used to indicate this person as the author when citingabotanical name.[11]

Loudon's publications include the books:

Designed by others in Loudon's 'Gardenesque' style:

In 1830, when Loudon was 47 years old, he asked a friend to invite the anonymous author of The Mummy! Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century to lunch. He had recently reviewed and admired the inventions in this novel in an article published in his Gardener's Magazine. Set in 2126 AD, it is an early example of science fiction. England had become an absolute monarchy and it featured an early Internet, espresso machines, and air-conditioning. The author turned out to be Jane Webb who, having been left penniless at 17 by the death of her father, had turned to writing as a profession. They married seven months later and had a daughter, Agnes, who later married the solicitor and political agent Markham Spofforth from 1858 until her death in 1863.

Loudon loved the fantastical and his wife's expression of it. Their marriage not only symbolized a mutual admiration of one another's minds, but a number of innovations in the world of gardening. Through her marriage, Jane Loudon encountered her husband's work and decided to create her own guides to make gardening more accessible to young women. The Loudons were considered the leading horticulturalists of their day, and their circle of friends included Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray.[citation needed]

Design of the municipal cemetery at Southampton was Loudon's final project. Despite advanced lung cancer, he corrected the final proofs for his latest encyclopaedia. He travelled to Bath to inspect the site for another cemetery; and then to Oxford to see a client. On his return to London, his doctor told him that he was dying; he died, penniless and in debt, in the arms of his wife in December 1843. He is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.[14]

Loudoun RoadinSt John's Wood is named after him, despite the different spelling.[15] A plaque jointly commemorating the Loudons was erected at their former home, 3 Porchester Terrace, Bayswater in 1953, by London County Council.

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Academics |

|

| Artists |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|