| The Kongo Cosmogram | |

|---|---|

| |

| Affiliation | Kongo religion · Hoodoo |

| Ethnic group | Kongo people |

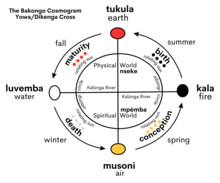

The Kongo cosmogram (also called yowa or dikenga cross, Kikongo: dikenga dia Kongoortendwa kia nza-n' Kongo) is a core symbol in Bakongo religion that depicts the physical world (Ku Nseke), the spiritual world (Ku Mpémba), the Kalûnga line that runs between the two worlds, the sacred river that forms a circle through the two worlds, the four moments of the sun, and the four elements.[1][2][3]

Ethnohistorical sources and material culture demonstrate that the Kongo cosmogram existed as a long-standing symbolic tradition within the BaKongo culture before European contact in 1482, and that it continued in use in Central Africa through the early twentieth century.[1] In its fullest embellishment, this symbol served as an emblematic representation of the Kongo people and summarized a broad array of ideas and metaphoric messages that comprised their sense of identity within the cosmos.[4]

The Kongo cosmogram was introduced in the Americas by enslaved Bakongo people in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.[5] Archaeological findings in the United States show evidence that the symbol was honored by Black Americans, who drew the Kongo cosmogram on the walls of church basements, as well as engraved it in pottery.[6]

| Part of a serieson |

| Kongo religion |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Diaspora |

|

|

|

|

The Bakongo believe that in the beginning, there was only a circular void of nothingness, called mbûngi.[7] The creator god Nzambi Mpungu summoned a spark of fire, or Kalûnga, that grew until it filled the mbûngi. When it grew too large, Kalûnga became a great force of energy and unleashed heated elements across space, forming the universe with the sun, stars, planets, etc.[7] Because of this, kalûnga is seen as the origin of life and a force of motion. The Bakongo believe that life requires constant change and perpetual motion. Nzambi Mpunga is also referred to as Kalûnga, the god of change.[8]

After creation, the nature of Kalûnga shifted when Nzambi separated the physical world, or Ku Nseke, from the spiritual (ancestral) world, or Ku Mpémba, with the Kalûnga line.[7] The line became a river, carrying people between the worlds at birth and death, and mbûngi became the rotating sun. At death, or the sun's setting, the process repeats, and a person is reborn. In Kikongo, the word Kalûnga means "threshold between worlds."[9] Accordingly, the Kalûnga line acts as a barrier between the two worlds and leads all Bakongo people, or muntu, through the four stages of life.[8]

Together, the Kalûnga line and the mbûngi circle form part of the Kongo cosmogram, also called the YowaorDikenga Cross.[7]Asimbi (pl. bisimbi) is a water spirit that is believed to inhabit bodies of water and rocks, having the ability to guide bakulu, or the ancestors, along the Kalûnga line to the spiritual world after death. They are also present during the baptismsofAfrican American Christians, according to Hoodoo tradition.[10][11]

According to Molefi Kete Asante, "Another important characteristic of Bakongo cosmology is the sun and its movements. The rising, peaking, setting, and absence of the sun provide the essential pattern for Bakongo religious culture. These 'four moments of the sun' equate with the four stages of life: conception, birth, maturity, and death. For the Bakongo, everything transitions through these stages: planets, plants, animals, people, societies, and even ideas. This vital cycle is depicted by a circle with a cross inside. In this cosmogram or dikenga, the meeting point of the two lines of the cross is the most powerful point and where the person stands."[7]

Then the process repeats and Bakongo are reborn. Together, Kalûnga and the mbûngi circle form the YowaorDikenga Cross. The four corners of the cross are believed to represent musoni time, kala time, tukula time, and luvemba time. They correspond to the four moments of the sun, the four stages of life, the four elements and the four seasons.[8]

Nature is also essential in the Kongo religion. While nature spirits later became more associated with water, or kalûnga, they were also known to dwell in the forest, or mfinda (findainHoodoo). The Kingdom of Kongo used the term chibila, which referred to sacred groves, where they would venerate these forest spirits. The Kingdom of Loango called them bakisi banthandu, or spirits of the wilderness.[12] The Kingdom of Ndongo preferred the name xibila (pl. bibila).[13]

The Kongo people also believed that some ancestors inhabited the forest after death and maintained their spiritual presence in their descendants' lives. These particular ancestors were believed to have died, traveled to Mpémba, and then were reborn as bisimbi. Thus, The Great Mfinda existed as a meeting point between the physical world and the spiritual world. The living saw it as a source of physical nourishment through hunting and spiritual nourishment through contact with the ancestors. One expert on Kongo religion, Dr. Fu-Kiau, even described some precolonial Kongo cosmograms with mfinda as a bridge between the two worlds.[12]

|

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religions |

| ||||

| Deities |

| ||||

| Elements |

| ||||

| Art |

| ||||

| Diaspora |

| ||||

|

Kingdom of Kongo

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topics |

| ||||||||

| Monarchy |

| ||||||||

| Economy |

| ||||||||

| Geography |

| ||||||||

| Languages |

| ||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||

| Military |

| ||||||||

|

Bantu religion and folklore

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main topics |

| ||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||

| Culture |

| ||||||||

| Bantu diaspora |

| ||||||||