This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this articlebyadding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Lambeth Conference" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

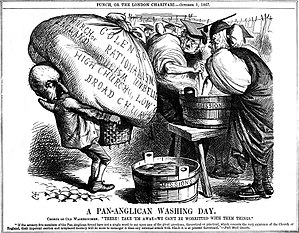

The Lambeth Conference is a decennial assembly of bishops of the Anglican Communion convened by the Archbishop of Canterbury. The first such conference took place at Lambeth in 1867.

As the Anglican Communion is an international association of autonomous national and regional churches and is not a governing body, the Lambeth Conferences serve a collaborative and consultative function, expressing "the mind of the communion" on issues of the day.[1]

Resolutions which a Lambeth Conference may pass are without legal effect, but they are nonetheless influential. So, although the resolutions of conferences carry no legislative authority, they "do carry great moral and spiritual authority."[This quote needs a citation] "Its statements on social issues have influenced church policy in the churches."[2]

These conferences form one of the communion's four "Instruments of Communion".[3]

The idea of these meetings was first suggested in a letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury by Bishop John Henry Hopkins of the Episcopal Diocese of Vermont in 1851. The possibility of such an international gathering of bishops had first emerged during the jubilee of the Church Missionary Society in 1851 when a number of US bishops were present in London.[4] However, the initial impetus came from episcopal churches in Canada. In 1865 the synod of that province, in an urgent letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury, (Charles Thomas Longley), represented the unsettlement of members of the Canadian church caused by recent legal decisions of the Privy Council and their alarm lest the revived action of convocation "should leave us governed by canons different from those in force in England and Ireland, and thus cause us to drift into the status of an independent branch of the Catholic Church".[5] They therefore requested him to call a "national synod of the bishops of the Anglican Church at home and abroad",[5] to meet under his leadership. After consulting both houses of the Convocation of Canterbury, Archbishop Longley assented and convened all the bishops of the Anglican Communion (then 144 in number) to meet at Lambeth in 1867.

Many Anglican bishops (amongst them the Archbishop of York and most of his suffragans) felt so doubtful as to the wisdom of such an assembly that they refused to attend it, and Dean Stanley declined to allow Westminster Abbey to be used for the closing service, giving as his reasons the partial character of the assembly, uncertainty as to the effect of its measures and "the presence of prelates not belonging to our Church".[6]

Archbishop Longley said in his opening address, however, that they had no desire to assume "the functions of a general synod of all the churches in full communion with the Church of England", but merely to "discuss matters of practical interest, and pronounce what we deem expedient in resolutions which may serve as safe guides to future action".[7]

The resolutions of the Lambeth Conferences have never been regarded as synodical decrees, but "their weight has increased with each conference."[citation needed]

Seventy-six bishops accepted the primate's invitation to the first conference, which met at Lambeth on 24 September 1867 and sat for four days, the sessions being in private. The archbishop opened the conference with an address: deliberation followed; committees were appointed to report on special questions; resolutions were adopted, and an encyclical letter was addressed to the faithful of the Anglican Communion. Each of the subsequent conferences has been first received in Canterbury Cathedral and addressed by the archbishop from the chair of St Augustine.[8]

From the Second Conference, they have then met at Lambeth Palace, and after sitting for five days for deliberation upon the fixed subjects and appointment of committees, have adjourned, to meet again at the end of a fortnight and sit for five days more, to receive reports, adopt resolutions and to issue their encyclical letter.[9]

From 1978 onwards the conference has been held on the Canterbury campus of the University of Kent allowing the bishops to live and worship together on the same site for the first time. In 1978 the bishops' spouses were accommodated at the nearby St Edmund's School (an Anglican private school); this separation of spouses was not felt helpful.[by whom?] Since 1988 the spouses have also lived at the university.

The Archbishop of York and several other English bishops refused to attend because they thought such a conference would cause "increased confusion" about controversial issues.[11]

The conference began with a celebration of the Holy Communion at which Henry John Whitehouse, the second Bishop of Illinois, preached; Wilberforce of Oxford later described the sermon as "wordy but not devoid of a certain impressiveness".[12]

The first session convened in the upstairs Dining Room (known as the Guard Room). The session was spent discussing a "preamble to the subsequent resolutions" that would be issued after the conference.[13]

Day two was spent on a discussion of synodical authority concluding that the faith and unity of the Anglican Communion would be best maintained by there being a synod above those of the "several branches".

Day three was given over[citation needed] to discussing the situation in the Diocese of Natal and its controversial bishop John William Colenso "who had been deposed and excommunicated for heresy because of his unorthodox views of the Old Testament."[10] Longley refused to accept a condemnatory resolution proposed by Hopkins, Presiding Bishop of the Americans, but they later voted to note 'the hurt done to the whole communion by the state of the church in Natal'. Of the 13 resolutions adopted by the conference, 2 have direct reference to the Natal situation.

Day four saw the formal signing of the address. There had been no plan for further debate but the bishops unexpectedly returned to the subject of Colenso, delaying the end of the conference. Other resolutions have to do with the creation of new sees and missionary jurisdictions, Commendatory Letters, and a voluntary spiritual tribunal in cases of doctrine and the due subordination of synods. It was agreed that the reports of the committees would be received at a final meeting on 10 December by those bishops still in England. On the final day, the bishops attended Holy Communion at Lambeth Parish Church at which Longley presided; Fulford of Montreal, one of the instigators of the original request, preached. No one session of the conference had all the bishops attending although all signed the Address and Longley was authorised to add the names of absent bishops who later subscribed to it. Attending bishops included 18 English, 5 Irish, 6 Scots, 18 American and 24 "Colonial".[14]

The Latin and Greek texts of the "encyclical" (as it rapidly became known) were produced by Wordsworth of Lincoln.[15]

Tait was a friend of Colenso and shared Dean Stanley's Erastian views (that the conference should not have been called without some royal authority) but when the Canadians again requested a Conference in 1872, he concurred. The American bishops suggested a further conference in 1874, Kerfoot of Pittsburgh delivering the request in person. Importantly, the Convocation of the Province of York had changed its position and now supported the Conference idea. 108 of the 173 bishops accepted the invitation, although the actual attendance was a little smaller. The first gathering was in Canterbury Cathedral on St Peter's Day, 29 June. The bishops then moved Lambeth for the First Session on 2 July, after Holy Communion at which Tait presided and Thomson of York preached, the bishops gathered in the library. One half day was assigned to each of the six main agenda areas. The reports of the special committees (based in part upon those of the committee of 1867) were embodied in the encyclical letter, which described the best mode of maintaining union, voluntary boards of arbitration, the relationship between missionary bishops and missionaries (a particular problem in India), chaplains in continental Europe, modern forms of infidelity and the best way of dealing with them and the condition, progress and needs of the churches. A final service of thanksgiving took place in St Paul's Cathedral on 27 July. Attending bishops included 35 English, 9 Irish, 7 Scots, 19 American and 30 "Colonial and Missionary". One bishop suffragan and a number of former colonial bishops with commissions in England also attended as full members. The costs of the conference were met by the English bishops and a programme of excursions was organised by the member of Parliament J. G. Talbot. The Latin and Greek texts of the encyclical were again produced by Wordsworth of Lincoln.

The agenda of this conference was noticeable for its attention to matters beyond the internal organisation of the Anglican Communion and its attempts to engage with some of the major social issues that the member churches were encountering. In addition to the encyclical letter, nineteen resolutions were put forth, and the reports of twelve special committees are appended upon which they are based, the subjects being intemperance, purity, divorce, polygamy, observance of Sunday, socialism, care of emigrants, mutual relations of dioceses of the Anglican Communion, home reunion, Scandinavian churches, Old Catholics, etc., Eastern Churches, standards of doctrine and worship. Importantly, this was the first conference to make use of the "Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral" as a basis for Anglican self-description. The Quadrilateral laid down a fourfold basis for home reunion: that agreement should be sought concerning the Holy Scriptures, the Apostles' and Nicene creeds, the two sacraments ordained by Christ himself and the historic episcopate.

This conference was held a year early because of the thirteenth centennial celebrations of St. Augustine's arrival in Kent. The first event was a visit by the bishops to the Augustine monument at Ebbsfleet. A special train was run by the South Eastern Railway that stopped at Canterbury to collect the cathedral clergy and choir. A temporary platform was built at Ebbsfleet for first class passengers; second class passengers had to alight at Minster-in-Thanet and walk the remaining 2.3 miles. After an act of worship the party retrained and proceeded to Richborough to visit the Roman remains and take tea. There is no station at Richborough, perhaps a second temporary one was created. The bishops then travelled back to Canterbury to be ready for the opening service of the conference on the following day. The arrangements did not go well and the Dean of Canterbury complained of 'the appalling mismanagement by the railway authorities'.[16]

One of the chief subjects for consideration was the creation of a tribunal of reference, but the resolutions on this subject were withdrawn due to opposition of the bishops of the Episcopal Church in the USA, and a more general resolution in favour of a "consultative body" was substituted. The encyclical letter is accompanied by sixty-three resolutions (which include careful provision for provincial organisation and the extension of the title archbishop "to all metropolitans, a thankful recognition of the revival of brotherhoods and sisterhoods, and of the office of deaconess," and a desire to promote friendly relations with the Eastern Churches and the various Old Catholic bodies), and the reports of the eleven committees are subjoined.

Davidson chafed under the arrangements for the conference in which he had played no part and determined to write the final encyclical himself. There were a number of unfortunate phrases in his draft to which many bishops objected but he refused to accept amendments on the day of its presentation. However, he reconsidered overnight and announced the following morning that he had changed the draft as requested. A bishop who rose to thank to express gratitude for his change of mind was rebuked with the words, "Sir you may thank me all you wish, but you must thank me in silence".[17]

The chief subjects of discussion were: the relations of faith and modern thought, the supply and training of the clergy, education, foreign missions, revision and "enrichment" of the Book of Common Prayer, the relation of the Church to "ministries of healing" (Christian Science, etc.), the questions of marriage and divorce, organisation of the Anglican Church, and reunion with other Churches. The results of the deliberations were embodied in seventy-eight resolutions, which were appended to the encyclical issued, in the name of the conference, by the Archbishop of Canterbury on 8 August.

The single most important action of this conference was to issue the "Appeal to all Christian People", which set out the basis on which Anglican churches would move towards visible union with churches of other traditions. The document repeated a slightly modified version of the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral and then called on other Christians to accept it as a basis on which to discuss how they may move toward reunion. The proposal did not arise from the formal debates of the conference but amongst a group of bishops talking over tea on the lawn of Lambeth Palace.

The conference's uncompromising and unqualified rejection of all forms of artificial contraception, even within marriage, was contained in Resolution 68, which said, in part:

We utter an emphatic warning against the use of unnatural means for the avoidance of conception, together with the grave dangers – physical, moral and religious – thereby incurred, and against the evils with which the extension of such use threatens the race. In opposition to the teaching which, under the name of science and religion, encourages married people in the deliberate cultivation of sexual union as an end in itself, we steadfastly uphold what must always be regarded as the governing considerations of Christian marriage. One is the primary purpose for which marriage exists, namely the continuation of the race through the gift and heritage of children; the other is the paramount importance in married life of deliberate and thoughtful self-control. [18]

The conference opened with a "day of devotion" at Fulham Palace, the residence of the Bishop of London. Holy Communion was celebrated at 8:30 am with an address by 86-year-old Edward Talbot, retired Bishop of Winchester.[19]

The conference's "manner of deliberations" followed the pattern used in earlier conferences. The six subjects (see the list of subjects in the Resolutions section below) proposed for consideration were brought before sessions of the whole Conference for six days, from July 7 to July 12. The subjects were all referred to committees. The work of the committees was aided by the essays and papers that had been prepared for them in advance. After their two-weeks of deliberations, the committees presented their reports and resolutions to the whole conference from July 28 to August 9.[24]

Seventy-five resolutions passed

The subjects on which resolutions were passed at the Conference are the following:[25]

I. the Christian Doctrine of God

II. the Life and Witness of the Christian Community

III. the Unity of the Church

IV. the Anglican Communion

V. the Ministry of the Church

VI. Youth and Its Vocation

Sampling of Resolutions by subject

The Conference adopted seventy-five Resolutions. They can all be seen at Anglican Communion Document Library: 1930 Conference.

I. Christian Doctrine of God: Resolutions 1–8

II. Life and Witness of the Christian Community

III. Unity of the Church: Resolutions 31–47

"The Conference encouraged the Unity of the Church in all parts of the world."[citation needed]

It was primarily concerned (1) with the relations of the Churches of the Anglican Communion to the Orthodox Churches of the East, and (2) with the Proposed Scheme of Union in South India, and (3) with the problems arising in Special Areas.[25] Various Churches sent delegations to consult with the Conference, notably the Old Catholics.[25]

IV. Anglican Communion: Resolutions 48–60

V. Ministry of the Church: Resolutions 61–74

Cost of the Conference

Traditionally the Archbishop of Canterbury bore the cost of a Lambeth Conference. For the 1930 Conference, the British Church Assembly provided £2,000. toward the cost. However, this was only a fraction of the total cost. One item, providing lunch and afternoon tea every day for five weeks, cost £1,400.[30]

This was the first conference not to take place in Lambeth Palace. This was because of the increase in the number of bishops attending, as well as the presence of almost 100 observers and consultants. Meetings were instead held at Church House, Westminster although the bishops, with their spouses, were invited to dinner at Lambeth by rotation.

This conference "recognised the autonomy of each of its member churches...legal right of each Church to make its own decision" about women priests. It also denounced the use of capital punishment and called for a common lectionary.

This was the first conference to be held on the campus of the University of Kent at Canterbury where every subsequent conference has been held.[32]

The 1978 Conference included forty assistant bishops.[33]

The conference dealt with the question of the inter-relations of Anglican international bodies and issues such as marriage and family, human rights, poverty and debt, environment, militarism, justice and peace. Women's ordination to the priesthood was also a major topic of discussion. Archbishop Michael Peers, Bishop Graham Leonard, Bishop Samir Kafity, and the Reverend Nan Arrington Peete spoke to the assembly on the topic.[34][35] Peete, who was ordained in the Episcopal Church USA, was the first female priest to speak at the Lambeth Conference.[36] The conference decided that "each province respect the decision of other provinces in the ordination or consecration of women to the episcopate."

At previous Lambeth Conferences, only bishops were invited to attend, but all members of the Anglican Consultative Council and representative bishops from the "Churches in Communion" (i.e. the Churches of Bangladesh, North and South India and Pakistan) were invited to attend.[37]

The most hotly debated issue at this conference was homosexuality in the Anglican Communion. It was finally decided, by a vote of 526–70, to pass a resolution (1.10) calling for a "listening process" but stating (in an amendment passed by a vote of 389–190)[38] that "homosexual practice" (not necessarily orientation) is "incompatible with Scripture" and that the Conference "cannot advise the legitimising or blessing of same sex unions nor ordaining those involved in same gender unions".[39] A subsequent public apology was issued to gay and lesbian Anglicans in a "Pastoral Statement" from 182 bishops worldwide, including eight primates (those of Brazil, Canada, Central Africa, Ireland, New Zealand, Scotland, South Africa and Wales),[40] and an attempt was made at conciliation the following year in the form of the Cambridge Accord. Division and controversy centred on this motion and its application continued to the extent that, ten years later, in 2007, Giles GoddardofInclusive Church suggested in published correspondence with Andrew Goddard across the liberal–evangelical divide: "It's possible to construct a perfectly coherent argument that the last 10 years have been preoccupied with undoing the damage Lambeth 1.10 caused to the Communion."[41]

A controversial incident occurred during the conference when Bishop Emmanuel Chukwuma of Enugu, Nigeria, attempted to exorcise the "homosexual demons" from Richard Kirker, a British priest and the general secretary of the Lesbian and Gay Christian Movement, who was passing out leaflets. Chukwuma told Kirker that he was "killing the church"; Kirker's civil response to the attempted exorcism was "May God bless you, sir, and deliver you from your prejudice against homosexuality."[42]

Reflecting on resolution 1.10 in the lead up to Lambeth 2022, Angela Tilby recalled the intervention of Bishop Michael Bourke, who successfully proposed an amendment which said: "We commit ourselves to listen to the experience of homosexual persons".[43] Tilby considered that while the amendment had appeared inconsequential at the time, it had indeed been significant: she said that the idea of "patient listening" underpinned the Church of England's process Living in Love and Faith.[43]

Discussions about a mission to fight poverty, create jobs and transform lives by empowering the poor in developing countries using innovative savings and microcredit programs, business training and spiritual development led to the formation of Five Talents.[44]

The fourteenth conference took place from 16 July to 4 August 2008 at the University of Kent's Canterbury campus. In March 2006 the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, issued a pastoral letter[45] to the 38 primates of the Anglican Communion and moderators of the united churches setting out his thinking for the next Lambeth Conference.

Williams indicated that the emphasis will be on training, "for really effective, truthful and prayerful mission". He ruled out (for the time being) reopening of the controversial resolution 1.10 on human sexuality from the previous Lambeth Conference, but emphasised the "listening process" in which diverse views and experiences of human sexuality were being collected and collated in accordance with that resolution and said it "will be important to allow time for this to be presented and reflected upon in 2008".

Williams indicated that the traditional plenary sessions and resolutions would be reduced and that "We shall be looking at a bigger number of more focused groups, some of which may bring bishops and spouses together."

Attendance at the Lambeth Conference is by invitation of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Invitations were sent to more than 880 bishops around the world for the Fourteenth Conference. Notably absent from the list of those invited are Gene Robinson and Martyn Minns. Robinson was the first Anglican bishop to exercise the office while in an acknowledged same-sex relationship, and Rowan Williams said it was "proving extremely difficult to see under what heading he might be invited to be around", drawing criticism.[46] Minns, the former rector of Truro Episcopal ChurchinFairfax, Virginia, was the head of the Convocation of Anglicans in North America, a splinter group of American Anglicans; the Church of Nigeria considered him a missionary bishop to the United States, despite protest from Canterbury and the U.S. Episcopal Church.

In 2008, four Anglican primates announced that they intended to boycott the Lambeth conference because of their opposition to the actions of Episcopal Church in the USA (the American province of the Anglican Communion) in favour of homosexual clergy and same-sex unions.[47][48] These primates represent the Anglican provinces of Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya and Rwanda. In addition, Peter Jensen, Archbishop of Sydney, Australia and Michael Nazir-Ali, Bishop of Rochester, among others announced their intentions not to attend.

The Global Anglican Future Conference, a meeting of conservative bishops held in Jerusalem in June 2008 (one month prior to Lambeth), was thought by some to be an "alternative Lambeth" for those who are opposed to the consecration of Robinson.[49] GAFCON involved Martyn Minns, Peter Akinola and other dissenters[50] who considered themselves to be in a state of impaired communion with the American Episcopal Church and the See of Canterbury.[citation needed] The June 2008 church blessing of a civil relationship between Peter Cowell, an Anglican chaplain at the Royal London Hospital and priest at Westminster Abbey, and David Lord, an Anglican priest serving at a parish in Waikato, New Zealand, renewed the debate one month prior to the conference. Martin Dudley, who officiated at the ceremony at St Bartholomew-the-Great, maintained that the ceremony was a "blessing" rather than a matrimonial ceremony.[51]

In 2008, the seven martyred members of the Melanesian Brotherhood were honoured during the concluding Eucharist of the 2008 conference at Canterbury Cathedral. Their names were added to the book of contemporary martyrs and placed, along with an icon, on the altar of the "Chapel of the Saints and Martyrs of Our Times". When the Eucharist was over, bishops and others came to pray in front of the small altar in the chapel.[52] The icon stands in the cathedral[53] as a reminder of their witness to peace and of the multi-ethnic character of global Anglicanism.

The ten-year cycle followed since 1948 would have suggested a Lambeth Conference in 2018. Justin Welby had replaced Rowan Williams in 2013, and against a backdrop of disagreement within the Anglican Communion over homosexuality, Welby declined to convene a conference until he had visited primates in their own countries,[55] and felt confident that the vast majority of bishops would attend.[56] Welby appointed a Design Group[57] under the chairmanship of Archbishop Thabo Makoba of Cape Town to plan for a conference in 2020.[58][59] Given the COVID-19 pandemic, the conference was delayed by two years.[60] With the theme, "God's Church to God's World",[61] the conference began on 27 July 2022. It lasted for 12 days with around 660 bishops in attendance.[54][62]

The conference once again included significant discussion of homosexuality and same-sex marriage, with a draft 'call'[b] with similarities to Resolution 1.10 from the 1998 conference being included in the conference's proceedings (which declared gay sex to be a sin).[63][64] On 2 August, Welby 'affirmed the validity' of Resolution 1.10 saying that it was "not in doubt".[64] This prompted criticism from several LGBTQ+ activists including Jayne Ozanne and Sandi Toksvig,[64][65][66] and the signing by 175 bishops and primates of a pro-LGBTQ statement asserting the holiness of the love of all committed same-sex couples.[67]

Five Talents is now 10 years old, or rather a little bit more than 10 years old, because at the 1998 Lambeth Conference I remember very vividly an evening where we were discussing the first principles of Five Talents; the occasion when some real substance was being put on the ideal and things were moving forward.

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

| General |

| |

| African provinces |

| |

| Pan-American provinces |

| |

| Asian provinces |

| |

| European provinces |

| |

| Oceanian provinces |

| |

| Extra-provincial churches |

| |

| Churches in full communion |

| |

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|