ꓡꓲ‐ꓢꓴ လီဆူ 傈僳 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 1,200,000 (est.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Lisu, Lipo, Laemae, Naw; Southwestern Mandarin (Chinese), Burmese, Thai | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Animism, and Buddhism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

| Lisu people | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese | 傈僳族 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Burmese name | |||||||

| Burmese | လီဆူလူမျိုး | ||||||

| Thai name | |||||||

| Thai | ลีสู่ | ||||||

The Lisu people (Lisu: ꓡꓲ‐ꓢꓴ ꓫꓵꓽ; Burmese: လီဆူလူမျိုး, [lìsʰù]; Chinese: 傈僳族; pinyin: Lìsùzú; Thai: ลีสู่) are a Tibeto-Burman ethnic group who inhabit mountainous regions of Myanmar (Burma), southwest China, Thailand, and the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh.

About 730,000 Lisu live in Lijiang, Baoshan, Nujiang, Dêqên and Dehong prefectures in Yunnan Province and Sichuan Province, China. The Lisu form one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by China. In Myanmar, the Lisu are recognized as one of 135 ethnic groups and an estimated population of 600,000. Lisu live in the north of the country; Kachin State (Putao, Myitkyina, Danai, Waingmaw, Bhamo), Shan State (Momeik, Namhsan, Lashio, Hopang, and Kokang) and southern Shan State (Namsang, Loilem, Mongton), and Sagaing Division (Katha and Khamti), Mandalay Division (Mogok and Pyin Oo Lwin). Approximately 55,000 live in Thailand, where they are one of the six main hill tribes. They mainly inhabit remote mountainous areas.[2]

The Lisu tribe consists of more than 58 different clans. Each family clan has its own name or surname. The biggest family clans well known among the tribe clans are Laemae pha, Bya pha, Thorne pha, Ngwa Pha (Ngwazah), Naw pha, Seu pha, Khaw pha. Most of the family names came from their own work as hunters in the primitive time. However, later, they adopted many Chinese family names. Their culture has traits shared with the Yi people or Nuosu (Lolo) culture.

Lisu history is passed from one generation to the next in the form of songs. Today, these songs are so long that they can take an entire night to sing.[3]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2017)

|

The Lisu are believed to have originated in eastern Tibet even before present Tibetans arrived in the plateau. Research done by Lisu scholars indicates that they moved to northwestern Yunnan. They inhabited a region across Baoshan and the Tengchong plain for thousands of years. Lisu, Yi, Lahu, and Akha are Tibetan–Burman languages, distantly related to Burmese and Tibetan.[4][5][6][7] After the Han Chinese Ming Dynasty, around 1140–1644 CE the eastern and southern Lisu languages and culture were greatly influenced by the Han culture.[8][9] Taiping village in Yinjiang, Yunnan, China, was first established by Lu Shi Lisu people about 1,000 years ago.[citation needed] In the mid-18th century, Lisu peoples in Yinjiang began moving into Momeik, Burma, a population of southern Lisu moved into Mogok, and southern Shan State, and then in the late 19th century, moved into northern Thailand.[9][10][11][12] Lisu is one of the three Lolo tribes, the descendants of Yi. Yi (or Nuosu) are still much closer to the Lisu and Myanmar languages. Myat Wai Toe observes that as the saying, "the Headwaters of the Great River, Lisu originates," where Lisu lived in "Mou-Ku-De"; they were not yet called "Lisu" until 400–200 BC.[13][better source needed]

Since the 2010s, many Lisu clashed with the Kachin over allegations of the KIA forcefully conscripting them and killing civilians.[14][15] During the Myanmar Civil War, the Lisu National Development Party formed pro-Tatmadaw militias to fight the KIA and the PDF. Both the youth and the elderly were conscripted into these "people's militias." U Shwe Min led these militias until his death on March 7, 2024.[16] [17][18]

Lisu people in India are called Yobin. In all government records, Lisu are Yobin, and the words are sometimes used interchangeably. In Lisu is one of the minority tribes of Arunachal Pradesh of India. They live mainly in Vijoynagar Circle at Gandhigram (or Shidi in Lisu) which is the largest village. Lisus are also found in Miao town and Injan village of Kharsang Circle Changlang District. The Lisu traditionally lived in the Yunnan Province of southwestern China and in Shan State and Kachin State of northeastern Myanmar. There are about 5,000 Lisu people in India.

Initially, the Indo-Burmese border had been drawn based on surveys conducted under the Topographical Survey of British India as early as 1912, following the highest ridge from the Hkakabo Razi (alt. 5,881 m (19,295 ft); the highest point in Myanmar) at the junction with the Chinese border in the north, to the Chittagong Hills in Bangladesh according to a "combination of ridges, watershed and highest crests".[19] Later, during World War II, G.D.L. Millar's diary recalls the escape of a party of 150 European, Indian and Kachin officials and civilians fleeing the advance of the Japanese in May 1942. They went from Putao (Kachin) to Margherita (Assam) via the Chaukan Pass, and followed the valley of the Noa-dihing river. Millar records that over a hundred miles of the Chaukan Pass, "there was no trace of man" either Lisu or any other tribe.[20] The border negotiations with China that led to the 1962 Sino-Indian War, and the intrusion of Chinese troops into the Indian State of Arunachal Pradesh, propelled the Government of India to secure its international borders in the North East region, defined as per the Topographical Survey of British India. The Assam Rifles Regiments who took control of the border area hired labourers from various tribes, including Lisus, to build the air strip at Vijoynagar. In 1969–70, 200 families were settled in the area.[21] In 2010, the population was estimated at 5500 including Gorkhali Jawan(Ex-Assam Rifles Pensioners and Lisus/Yobin).[citation needed]

Some groups of Lisu arrived in India via the Ledo Road. Some of them worked as coal miners under British (One certificate that originally belonged to one Aphu Lisu is a British coal miner's certificate from 1918, preserved by the Lisu). The certificate bears the mark of the then governor who ruled the region from Lakhimpur, Assam (the section of Ledo road between Ledo and Shingbwiyang was only opened in 1943). Most of the Lisu who lived in Assam went back to Myanmar. However, some are still found in the Kharangkhu area of Assam, Kharsang Circle of Arunachal Pradesh. While most have lost their mother tongue, some have preserved the language and culture almost intact.[22][23]

In the early 1980s, the Lisu people living in India did not have Indian citizenship as they were considered refugees from Myanmar. In 1994, Indian citizenship was granted to them, but not Scheduled Tribe status. This is currently the subject of a claim to the Government.

Except for the arrival of a fleet of jeeps in the late 1970s, the area has been without roads and vehicles for 4 decades. The area is isolated, hence some describing the people as "prisoners of geography".[24]

In fact, Namdapha was originally declared a Wildlife Sanctuary in 1972, then a National Park in 1983. The authorities demarcated the southern boundary near Gandhigram village. Since then the Lisus settling in the National Park are considered as "encroachers" as per the Wildlife Protection Act 1972.[25] Between 1976 and 1981, a 157-kilometre (98 mi) road was made between Miao and Vijoynagar (MV road) by the Public Works Department following the left bank of the Noa-dihing river through Namdapha National Park but proved difficult to maintain due to extreme rainfall and frequent landslides. It was also felt that a road would further facilitate wildlife poaching and land encroachment in the National Park. Renovation of the MV road was announced in 2010 and 2013.[26]

Lisu villages are usually built close to water to provide easy access for washing and drinking.[8] Their homes are usually built on the ground and have dirt floors and bamboo walls, although an increasing number of the more affluent Lisu are now building houses of wood or even concrete.[3]

Lisu subsistence was based on paddy fields, mountain rice, fruit and vegetables. However, they have typically lived in ecologically fragile regions that do not easily support subsistence. They also faced constant upheaval from both physical and social disasters (earthquakes and landslides; wars and governments). Therefore, they have typically been dependent on trade for survival. This included work as porters and caravan guards. With the introduction of the opium poppy as a cash crop in the early 19th century, many Lisu populations were able to achieve economic stability. This lasted for over 100 years, but opium production has all but disappeared in Thailand and China due to interdiction of production. Very few Lisu ever used opium, or its more common derivative heroin, except for medicinal use by the elders to alleviate the pain of arthritis.[27]

The Lisu practiced swidden (slash-and-burn) agriculture. In conditions of low population density where land can be fallowed for many years, swiddening is an environmentally sustainable form of horticulture. Despite decades of swiddening by hill tribes such as the Lisu, northern Thailand had a higher proportion of intact forest than any other part of Thailand. However, with road building by the state, logging (some legal, but mostly illegal) by Thai companies,[28][29] enclosure of land in national parks, and influx of immigrants from the lowlands, swidden fields can not be fallowed, can not re-grow, and swiddening results in large swathes of deforested mountainsides. Under these conditions, Lisu and other swiddeners have been forced to turn to new methods of agriculture to sustain themselves.[30]

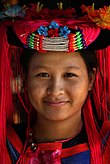

The Thai Lisu traditional costume shown here is much different from the main Lisu traditional costume being widely used in Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, China and Putao, Danai, Myitkyina, Northern Myanmar.[3]

Beginning in the early-20th century, many Lisu people in India and Burma converted to Christianity. Missionaries such as James O. Fraser, Allyn Cooke and Isobel Kuhn and her husband, John, of the China Inland Mission (now OMF International), were active with the Lisu of Yunnan.[31] Among the missionaries, James Outram Fraser (1880–1938) was the first missionary to reach the Lisu people in China. Another missionary who evangelized Lisu people in Myanmar was Thara Saw Ba Thaw (1889–1968). James Fraser and Saw Ba Thaw together created the Lisu alphabet in 1914.[32] There were many other missionaries who brought Christianity to Lisu people. David Fish says, "There were over a hundred missionaries who committed their life for spreading the Gospel among the Lisu people. They came from different denominations and mission; China Inland Mission, Disciples of Christ (Church of Christ), Assembly of God, Pentecostal Churches, and so on. The Lisu people accepted those missionaries and their teaching the Gospel so that they converted into Christianity quickly to be followers of Christ.[33]

The first missionaries in China and Myanmar were Russell Morse and his wife, Gertrude Erma Howe, who became Gertrude Morse after marriage with Russell Morse. The Missionaries of Christian Churches or Church of Christ in Myanmar were Morse families.[34] Their mission record notes that the Morse family started their mission in China in 1926 but, due to political unrest, they traveled to Burma and began teaching among Lisu tribe in 1930.[35]

The Lisu people's conversion to Christianity was relatively fast. Many Lisu and Rawang converted to Christianity from animism. Before World War II, the Lisu tribes who lived in Yunnan, China and Ah-Jhar River valley, Myanmar, were evangelized by missionaries from Tibetan Lisuland Mission and Lisuland Churches of Christ. Many Lisu then converted to Christianity.[36][better source needed]

The missionaries promoted education, agriculture, and health care. The missionaries created the Lisu written language and new opportunities. David Fish reports that, "J. Russell Morse brought many kinds of fruit such as Washington, Orange, Ruby, King-Orange, and grapefruit. Fruit cultivation spread from Putao to other parts of Myanmar and become an important national asset. He also trained the people the art of carpentry and the construction of buildings. And the Lisu people had also learned the strategy of Church planting from them."[37]

The missionaries studied Lisu culture so they could rapidly spread Christianity. They used various kind of methods, including teaching hymns, sending medicines and doctors, helping the needy, and providing the funds for domestic missionaries and evangelists. They also helped in developing Lisu agriculture.

The Chinese government's Religious Affairs Bureau has proposed considering Christianity as the official religion of the Lisu.[38]

As of 2008[update], there were more than 700,000 Christian Lisu in Yunnan, and 450,000 in Myanmar (Burma). Only the Lisu of Thailand have remained unchanged by Christian influences.[39][40]

Before Christianity was introduced to Lisu people, they were animists. Archibald Rose points that the religion of the Lisus appears to be a simple form of animism or nat-worship, sacrifices being offered to the spirits of the mountains.[41] Most important rituals are performed by shamans. The main Lisu festival corresponds to Chinese New Year and is celebrated with music, feasting and drinking, as are weddings; people wear large amounts of silver jewelry and wear their best clothes at these times as a means of displaying their success in the previous agricultural year. In each traditional village there is a sacred grove at the top of the village, where the sky spirit or, in China, the Old Grandfather Spirit, are propitiated with offerings; each house has an ancestor altar at the back of the house.[42][43][44]

Linguistically, Lisu belong to the Yi language or Nuosu branch of the Sino-Tibetan family.[45]

There are two scripts in use. The Chinese Department of Minorities publishes literature in both. The oldest and most widely used one is the Fraser alphabet developed about 1920 by James O. Fraser and the ethnic Karen evangelist Ba Thaw. The second script was developed by the Chinese government and is based on pinyin.

Fraser's script for the Lisu language was used to prepare the first published works in Lisu which were a catechism, portions of scripture, and a complete New Testament in 1936. In 1992, the Chinese government officially recognized the Fraser alphabet as the official script of the Lisu language.[46]

Only a small portion of Lisu are able to read or write the script, with most learning to read and write their local language (Chinese, Thai, Burmese) through primary education.[citation needed]

|

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Underlined: the 56 recognized ethnic groups | |||||||||||

| Sino-Tibetan |

| ||||||||||

| Austroasiatic |

| ||||||||||

| Austronesian |

| ||||||||||

| Hmong-Mien |

| ||||||||||

| Mongolic |

| ||||||||||

| Kra–Dai |

| ||||||||||

| Tungusic |

| ||||||||||

| Turkic |

| ||||||||||

| Indo-European |

| ||||||||||

| Others |

| ||||||||||

| Related |

| ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

|

| |

|---|---|

| Major tribes |

|

| Scheduled tribes (Recognised by government) |

|

| Other tribes (Not recognised by government) |

|

|

| |

|---|---|

| Kachin (12) |

|

| Kayah (9) |

|

| Kayin (Karen) (11) |

|

| Chin (53) |

|

| Bamar (Burman) (9) |

|

| Mon (1) |

|

| Rakhine (Arakanese) (7) |

|

| Shan (33) |

|

| Unrecognised / Others |

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kra–Dai |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Austronesian |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Austroasiatic |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Sino-Tibetan |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Hmong–Mien |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Other |

| ||||||||||||||||