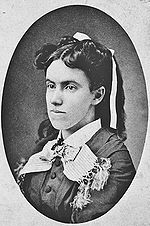

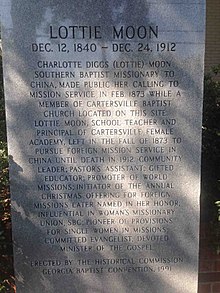

Charlotte Digges "Lottie" Moon

| |

|---|---|

Missionary to China

| |

| Born | (1840-12-12)December 12, 1840 |

| Died | December 24, 1912(1912-12-24) (aged 72)

Kobe Harbor, Japan

|

| Religion | Southern Baptist |

Charlotte Digges "Lottie" Moon (December 12, 1840 – December 24, 1912) was an American Southern Baptist missionary to China with the Foreign Mission Board who spent nearly 40 years (1873–1912) living and working in China. As a teacher and evangelist she laid a foundation for traditionally solid support for missions among Southern Baptists, especially through its Woman's Missionary Union.

Moon was born to affluent parents who were staunch Baptists, Anna Maria Barclay and Edward Harris Moon. She grew up on the family's ancestral 1,500 acres (6.1 km2) tobacco plantation called Viewmont,[1] near Scottsville, Virginia. Lottie was fourth in a family of five girls and two boys. Lottie was only thirteen when her father died in a riverboat accident.

The Moon family valued education, and at age fourteen Lottie went to school at the Baptist-affiliated Virginia Female Seminary (high school, later Hollins University) and Albemarle Female Institute in Charlottesville, Virginia.[2] In 1861 Moon received one of the first Master of Arts degrees awarded to a woman by a southern institution. She learned Latin, Greek, French, and Italian. Later, she would become an expert at Chinese.

A spirited and outspoken girl, Lottie was indifferent to her Christian upbringing until her early teens. She underwent a spiritual awakening after a series of revival meetings on the college campus. John Broadus, one of the founders of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, led the revival meeting in 1858 where Moon experienced this awakening.[citation needed]

Although educated females in the mid-19th century generally had few career opportunities, her older sister Orianna became a physician and served as a Confederate Army doctor during the American Civil War. Lottie helped her mother maintain the family estate during the war, and afterward began a teaching career. She taught at female academies, first in Danville, Kentucky. In Cartersville, Georgia, Moon and her friend, Anna Safford, opened Cartersville Female High School in 1871. Moon also joined the First Baptist Church and ministered to the impoverished families of Bartow County, Georgia.[citation needed]

To the family's surprise, Lottie's younger sister Edmonia accepted a call to go to north China as the first single woman Baptist missionary in 1872.[3] By this time, the Southern Baptist Convention had relaxed its policy against sending single women into the mission field, and Lottie soon felt called to follow her sister to China. On July 7, 1873, the Foreign Mission Board officially appointed 32-year-old Lottie as a missionary to China.[citation needed]

Lottie joined her sister Edmonia at the North China Mission Station in the treaty port of Dengzhou, in Shandong, (see Penglai, Prefecture City Yantai) and began her ministry by teaching in a boys school. (Edmonia had to return home a short time later for health reasons.) While accompanying some of the seasoned missionary wives on "country visits" to outlying villages, Lottie discovered her passion: direct evangelism. Most mission work at that time was done by married men, but the wives of China missionaries Tarleton Perry Crawford and Landrum Holmes had discovered an important reality: Only women could reach Chinese women. Lottie soon became frustrated, convinced that her talent was being wasted and could be better put to use in evangelism and church planting. She had come to China to "go out among the millions" as an evangelist, only to find herself relegated to teaching a school of forty "unstudious" children. She felt chained down, and came to view herself as part of an oppressed class - single women missionaries. Her writings were an appeal on behalf of all those who were facing similar situations in their ministries. In an article titled "The Woman's Question Again," published in 1883, Lottie wrote:

Can we wonder at the mortal weariness and disgust, the sense of wasted powers and the conviction that her life is a failure, that comes over a woman when, instead of the ever broadening activities that she had planned, she finds herself tied down to the petty work of teaching a few girls?[4]

Lottie waged a slow but relentless campaign to give women missionaries the freedom to minister and have an equal voice in mission proceedings. A prolific writer, she corresponded frequently with H. A. Tupper, head of the Southern Baptist Foreign Mission Board, informing him of the realities of mission work and the desperate need for more workers—both women and men.

In 1885, at the age of 45, Moon gave up teaching and moved into the interior to evangelize full-time in the areas of P'ingtu and Hwangshien. Her converts numbered in the hundreds. Continuing a prolific writing campaign, Moon's letters and articles poignantly described the life of a missionary and pleaded the "desperate need" for more missionaries, which the poorly funded board could not provide. She encouraged Southern Baptist women to organize mission societies in the local churches to help support additional missionary candidates, and to consider coming themselves. Many of her letters appeared as articles in denominational publications. Then, in 1887, Moon wrote to the Foreign Mission Journal and proposed that the week before Christmas be established as a time of giving to foreign missions. Catching her vision, Southern Baptist women organized local Women's Missionary Societies and even Sunbeam Bands for children to promote missions and collect funds to support missions. Moon was instrumental in the founding of The Woman's Missionary Union, an auxiliary to the Southern Baptist Convention, in 1888.[5] The first "Christmas offering for missions" in 1888 collected over $3,315, enough to send three new missionaries to China.

| Southern Baptists |

|---|

|

Background |

|

Beliefs |

|

People |

|

Related organizations |

|

Seminaries |

|

|

In 1892, Moon took a much needed furlough in the US, and did so again in 1902. She was very concerned that her fellow missionaries were burning out from lack of rest and renewal and going to early graves. The mindset back home was "go to the mission field, die on the mission field." Many never expected to see their friends and families again. Moon argued that regular furloughs every ten years would extend the lives and effectiveness of seasoned missionaries.

Throughout her missionary career, Moon faced plague, famine, revolution, and war. The First Sino-Japanese War (1894), the Boxer Rebellion (1900) and the Chinese Nationalist uprising (which overthrew the Qing Dynasty in 1911) all profoundly affected mission work. Famine and disease took their toll, as well. When Moon returned from her second furlough in 1904, she was deeply struck by the suffering of the people who were literally starving to death all around her. She pleaded for more money and more resources, but the mission board was heavily in debt and could send nothing. Mission salaries were voluntarily cut. Unknown to her fellow missionaries, Moon shared her personal finances and food with anyone in need around her, severely affecting both her physical and mental health. In 1912, she only weighed 50 pounds. Alarmed, fellow missionaries arranged for her to be sent back home to the United States with a missionary companion. However, Moon died en route at the age of 72, on December 24, 1912, in the harbor of Kobe, Japan.

Her body was cremated and the remains returned to her family in Crewe, Virginia, for burial.[6]

Rumors characterize Moon's relationship with Crawford Howell Toy, a former teacher who became a controversial figure among Southern Baptists in the late 19th century, as romantic. Moon first met Toy at the Albemarle Female Institute. Lottie—who previously learned Latin, Greek, French, Italian and Spanish and would become one of the first women to earn a master's degree in languages—studied Hebrew and English grammar under Toy's tutelage. Toy wrote of Moon, "She writes the best English I have ever been privileged to read." While some contend Toy proposed to Moon before the Civil War,[citation needed] her mention of a marriage proposal from Toy dates from 1881. In the interim, Toy supported the Confederacy and became a professor of Old Testament studies at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, while Moon aided her mother on their Virginia estate.[7]

However, following controversies concerning Darwinism and Toy's criticism of some Baptists' Christological Old Testament interpretations, Toy submitted his resignation from Southern in 1879. Moon's 1881 correspondence with FMB secretary H. A. Tupper, mentions her plans for a spring wedding with Toy, who was by then teaching Old Testament and religion at Harvard University. However, the engagement was broken and their marriage never occurred, with vague mentions of religious reasons. Toy's controversial new beliefs regarding the Bible, as well as Moon's commitment to remain in China doing mission work for Southern Baptists seem involved. Toy ultimately broke his affiliation with Southern Baptists and became a Unitarian.[8]

Lottie Moon has come to personify the missionary spirit for Southern Baptists and many other Christians as well. The annual Lottie Moon Christmas Offering for International Missions has raised a total of $1.5 billion for missions since 1888, and finances half the international missions budget of the Southern Baptist Convention every year.

In terms of feminist historiography, Regina Sullivan argues that the decision of the Southern Baptists to allow women to engage in foreign mission work fit in well with the Protestant expectation that women ought to be the most pious members of society, influencing men to lead moral lives. However Moon was impatient with the usual restraints, and deliberately moved her China mission out of reach of male authority. Furthermore, she went so far as to persuade Southern Baptist women to form their own missionary organizations. However, Moon's feminist leadership was not followed by women back home. The Women's Missionary Union made her appear a martyr to the Christian cause rather than a feminist voice within the Baptist Church. Sullivan emphasizes Moon was a pioneer for gender equality; as she wrote from China in 1893, "What women have a right to demand is perfect equality."[9]

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Other |

|