Marino Sanuto (orSanudo) Torsello (c. 1270–1343) was a Venetian statesman and geographer. He is best known for his lifelong attempts to revive the crusading spirit and movement; with this objective he wrote his Liber Secretorum Fidelium Crucis (Secrets for True Crusaders).

He is now sometimes referred to as Marino Sanuto the Elder to distinguish him from the later Venetian diarist of the same name.

Marino Sanuto was born in Venice around 1270 to the Sanudos, an aristocratic trading family active in the eastern Mediterranean, of which a branch had settled in the Aegean on the island of Naxos shortly after the Fourth Crusade and founded the Duchy of the Archipelago. Sanuto's father was a member of the Venetian Senate.[1]

Starting as a young man, he traveled extensively. As a teenager he stayed in Acre, a thriving commercial port and the final stronghold of the Crusader states before falling to a Malmuk siege in 1291. Later travels took him to Greece, Romania, Palestine, Egypt, Armenia, Cyprus and Rhodes. Sanuto became a member of the entourage of Giovanni Dandolo, the Doge of Venice. In 1305 he was at the court of Palermo and then went on to Rome where he joined the offices of Cardinal Riccardo Petroni. He was also involved in business affairs for the Sanuto family.[1]

In addition to his own travels, Sanuto had an extensive network of contacts who had travelled widely. Among his correspondents were Guglielmo Bernardi de Furvo, a Venetian nobleman who had travelled extensively in Muslim and Mongol lands, Bishop Jerome of Kaffa, in the Crimea, who in 1312 had been sent to reinforce the Catholic mission in China, and Andronikos II Palaiologos, the Emperor of Byzantium.[2]

For much of his life, Sanuto was a zealous advocate for a crusade to recapture the Holy Lands. Impetus for his interest in this cause is not entirely clear. Perhaps, like many Europeans, he was shocked by the sudden and unexpected fall of Acre to Muslim forces not long after his visit to the city. He may also have been influenced by his patron, Ricardo of Siena, a well-known proponent of a new crusade.[3]

During the early part of the thirteenth century, numerous crusade proposals were circulating in Europe. Opinions varied on preparations and implementation but Sanuto's plan placed more emphasis on a sophisticated military strategy and reliable financial backing as keys to a successful campaign. He detailed a long-term campaign to break down Muslim resistance around the former crusader states. Sanuto's proposal began with a multi-year blockade against Egypt, followed by the capture of the sultanate to secure Egypt and serve as a springboard for invasion of the Holy Land. He detailed precise military manoeuvres and even budgeted their daily costs.[4]

The first version of his treatise, Secreta fidelium crucis (Secrets for True Crusaders), was written between 1306 and 1307 and presented to Pope Clement V. Over the years he continued to revise and expand his manuscript, adding a history of the Holy Lands to 1307 and a geography of the Levant. In 1321 Sanuto presented his new version to Pope John XXII and a French translation was sent to King Charles IV of France.[5] The Liber Secretorum was copied numerous times and lavishly illustrated versions were sent to influential people throughout Europe. At least eleven copies are known to survive.[6]

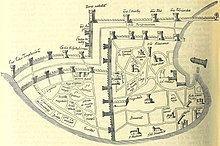

Another distinguishing feature of his crusade treatise was the inclusion of a set of maps depicting the Eastern Mediterranean, Arabia, Egypt, the Black Sea, Italy, and Western Europe. These are the earliest surviving maps from the Middle Ages designed for strategic military purposes. Also included was a revolutionary world map which combined elements of a traditional medieval mappamundi with the accuracy of a portolan chart.[6] It has been called "perhaps the single most important surviving cartographic artifact of the early 14th Century."[7]

At one time, Sanuto was thought to have been the creator of these maps but further study has shown that Pietro Vesconte, a Genoese cartographer, was the primary author. The degree of collaboration between Sanuto and Vesconte is unknown but Sanuto never mentions his cartographer by name.[6]

In addition to his crusade advocacy, Sanuto wrote a valuable Latin history of the Frankish principalities and Byzantium. The only surviving copy is a Venetian translation, Istoria del regno di Romania. Written between 1326 and 1333, his history provides a unique account of the reconquest of Constantinople by Michael VIII Palaiologos. Sanuto also wrote a brief account of the collapse of the Latin Empire of Constantinople and the efforts of Baldwin II to promote a reconquest.[8]

![]() Media related to Marino Sanudo sr at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Marino Sanudo sr at Wikimedia Commons

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|