This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Medieval Hebrew | |

|---|---|

| עִבְרִית Ivrit | |

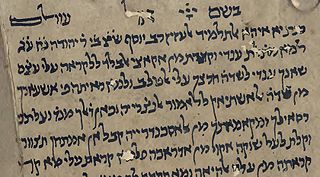

Excerpt from 13th–14th-century manuscript of the Hebrew translation of The Guide for the Perplexed

| |

| Region | Jewish diaspora |

| Era | Academic language used from the death of Hebrew as a spoken language in the 4th century until its revival as a spoken language in the 19th century. Developed into Modern Hebrew by the 19th century |

Early forms | |

| Hebrew abjad | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Medieval Hebrew was a literary and liturgical language that existed between the 4th and 19th century. It was not commonly used as a spoken language, but mainly in written form by rabbis, scholars and poets. Medieval Hebrew had many features distinguishing it from older forms of Hebrew. These affected grammar, syntax, sentence structure, and also included a wide variety of new lexical items, which were either based on older forms or borrowed from other languages, especially Aramaic, Koine Greek and Latin.[1]

In the Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain, important work was done by grammarians in explaining the grammar and vocabulary of Biblical Hebrew; much of this was based on the work of the grammarians of Classical Arabic[citation needed]. Important Hebrew grammarians were Judah ben David Hayyuj and Jonah ibn Janah. A great deal of poetry was written, by poets such as Dunash ben Labrat, Solomon ibn Gabirol, Judah Halevi, David Hakohen Abraham ibn Ezra and Moses ibn Ezra, in a "purified" Hebrew based on the work of these grammarians, and in Arabic quantitative metres (see piyyut). This literary Hebrew was later used by Italian Jewish poets.[2] The need to express scientific and philosophical concepts from Ancient Greek and medieval Arabic motivated Medieval Hebrew to borrow terminology and grammar from these other languages, or to coin equivalent terms from existing Hebrew roots, giving rise to a distinct style of philosophical Hebrew. Many have direct parallels in medieval Arabic. The ibn Tibbon family, and especially Samuel ibn Tibbon, were personally responsible for the creation of much of this form of Hebrew, which they employed in their translations of scientific materials from the Arabic.[3] At that time, original Jewish philosophical and theological works produced in Spain were usually written in Arabic,[1] but as time went on, this form of Hebrew was used for many original compositions as well.[citation needed]

Another important influence was Maimonides, who developed a simple style based on Mishnaic Hebrew for use in his law code, the Mishneh Torah. Subsequent rabbinic literature is written in a blend between this style and the Aramaicized Mishnaic Hebrew of the Talmud.[citation needed]

By late 12th and early 13th centuries the cultural center of Mediterranean Jewry was transferred from an Islamic context to Christian lands. The written Hebrew used in Northern Spain, Hachmei Provence (a term for all of Occitania) and Italy was increasingly influenced by Latin, particularly in philosophical writings, and also by different vernaculars (Provençal, Italian, French etc.).[4] In Italy we witness the flourishing of a new genre, Italian-Hebrew philosophical lexicons. The Italian of these lexicons was generally written in Hebrew characters and are a useful source for the knowledge of Scholastic philosophy among Jews. One of the earliest lexicons was that by Moses b. Shlomo of Salerno, who died in the late 13th. century; it was meant to clarify terms that appear in his commentary on Maimonides' The Guide for the Perplexed. Moses of Salerno's glossary was edited by Giuseppe Sermoneta in 1969. There are also glossaries associated with Jewish savants who befriended Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. Moses of Salerno's commentary on the Guide also contains Italian translations of technical terms, which brings the Guide's Islamic-influenced philosophical system into confrontation with 13th-century Italian scholasticism.[citation needed]

Hebrew was also used as a language of communication among Jews from different countries, particularly for the purpose of international trade.[citation needed]

Mention should also be made of the letters preserved in the Cairo Geniza, which reflect the Arabic-influenced Hebrew of medieval Egyptian Jewry. The Arabic terms and syntax that appear in the letters constitute a significant source for the documentation of spoken medieval Arabic, since Jews in Islamic lands tended to use colloquial Arabic in writing rather than classical Arabic, which is the Arabic that appears in Arabic medieval sources.[citation needed]

|

| |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overviews |

| ||||||||||||

| Eras |

| ||||||||||||

| Reading traditions |

| ||||||||||||

| Orthography |

| ||||||||||||

| Phonology |

| ||||||||||||

| Grammar |

| ||||||||||||

| Academic |

| ||||||||||||

| Reference works |

| ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afroasiatic |

| ||||||||||||

| Indo-European |

| ||||||||||||

| Others |

| ||||||||||||

| Sign languages |

| ||||||||||||

Italics indicate extinct languages | |||||||||||||