Miguel Covarrubias, also known as José Miguel Covarrubias Duclaud (22 November 1904 — 4 February 1957) was a Mexican painter, caricaturist, illustrator, ethnologist and art historian. Along with his American colleague Matthew W. Stirling, he was the co-discoverer of the Olmec civilization.[1]

José Miguel Covarrubias Duclaud was born on 22 November 1904 in Mexico City.[2] After graduating from the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria at the age of 14, he started producing caricatures and illustrations for texts and training materials published by the Mexican Ministry of Public Education.[2] He also worked for the Ministry of Communications.[citation needed]

In 1923, at the age of 19, he moved to New York City armed with a grant from the Mexican government, tremendous talent, but very little English.[2] In her book Covarrubias, author Adriana Williams writes that Mexican poet José Juan Tablada and New York Times critic/photographer Carl Van Vechten introduced him to New York's literary/cultural elite (known as the Smart Set).[citation needed] Soon Covarrubias was drawing for several top magazines, eventually becoming one of Vanity Fair magazine's premier caricaturists.

A man of many talents, he also began to design sets and costumes for the theater including Caroline Dudley Reagan's La Revue Negre starring Josephine Baker in the show that made her a smash in Paris. Other shows included Androcles and the Lion, The Four Over Thebes, and the Garrick Gaities' Rancho Mexicano number for dancer and choreographer Rosa Rolando (or Rolanda; born Rosemonde Cowan, and later to take the name Rosa Covarrubias). The two fell in love and traveled together to Mexico, Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean in the mid to late 1920s. During one of their trips to Mexico, Rosa and Miguel travelled with Tina Modotti and Edward Weston, who taught Rosa photography. Rosa was also introduced to Miguel's family and friends including artist Diego Rivera. Rosa would become lifelong friends with Rivera's third wife, the artist Frida Kahlo.

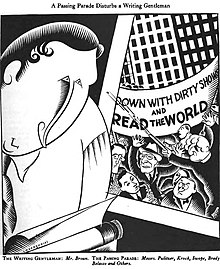

Miguel's artwork and celebrity caricatures have been featured in The New Yorker and Vanity Fair magazines.[3] The linear nature of his drawing style was highly influential to other caricaturists such as Al Hirschfeld. Miguel's first book of caricatures The Prince of Wales and Other Famous Americans was a hit, though not all his subjects were thrilled that his sharp, pointed wit was aimed at them. He immediately fell in love with the Harlem jazz scene, which he frequented with Rosa and friends including Eugene O'Neill and Nickolas Muray. He counted many notables among his friends including Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes , and W.C. Handy for whom he also illustrated books. Miguel's caricatures of the jazz clubs were the first of their kind printed in Vanity Fair. He managed to capture the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance in much of his work as well as in his book, Negro Drawings. He did not consider these caricatures, but serious drawings of people, music, and a culture he loved. Covarrubias also did illustrations for George Macy, the publisher of The Limited Editions Club, including Uncle Tom's Cabin, Green Mansions, Herman Melville's Typee, and Pearl Buck's All Men Are Brothers. Heritage Press, the sister organization of The Limited Editions Club, reprinted unsigned editions. In addition, he did illustrations for publisher Alfred & Charles Boni's Frankie and Johnny for a young writer who would become a good friend and film director named John Huston. Today, these editions are highly sought after by collectors.

He collaborated with Austrian Artist Wolfgang Paalen's journal Dyn from 1942 to 1944. Additionally, his advertising, painting, and illustration work brought him international recognition including gallery shows in Europe, Mexico, and the United States as well as awards such as the 1929 National Art Directors' Medal for painting in color for his work on a Steinway & Sons piano advertisement.

Covarrubias was invited by the 1939-1940 Golden Gate International Exposition (GGIE) that was held on Treasure Island, "to create a mural set entitled Pageant of the Pacific to be the centerpiece of Pacific House, a center where the social, cultural and scientific interests of the countries in the Pacific Area could be shown to a large audience.'"[4] Covarrubias painted the six murals for GGIE in San Francisco with his assistant Antonio M. Ruiz. The set of murals featured oversized, "illustrated maps entitled: The Fauna and Flora of the Pacific, Peoples, Art and Culture, Economy, Native Dwellings, and Native Means of Transportation. These murals were immensely popular at the GGIE and were later exhibited at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Upon returning to San Francisco, five of the murals were installed at the World Trade Club in the Ferry Building where they hung until 2001. The whereabouts of the sixth mural, Art and Culture, is unknown and has been the subject of great speculation."[4]

The Fauna and Flora of the Pacific mural is on display at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. "The colorful map depicts the four Pacific Rim continents with examples of their flora and fauna suspended in a swirling Pacific Ocean populated with sea creatures."[4]

Miguel and Rosa married in 1930 and they took an extended honeymoon to Bali with the National Art Directors' Medal prize money where they immersed themselves in the local culture, language, and customs.[3] Miguel returned to Southeast Asia (Java, Bali, India, Vietnam) in 1933, as a Guggenheim Fellow with Rosa whose photography would become part of Miguel's book, Island of Bali. The book and particularly the marketing for months surrounding its release, contributed to the 1930s Bali craze in New York. He also spent time in China, where his work was very influential among artists in Shanghai.[5]

Rosa and Miguel returned to live in Mexico City where he continued to paint, illustrate, and write. Their home, Tizapán, would become a hub for visitors from around the world including the likes of Nickolas Muray, Dolores del Río, and Nelson Rockefeller. He taught ethnology at the Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia and was appointed artistic director and director of administration for a new department at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, the National Palace of Fine Arts. His mandate was to add an Academy of Dance - a task to which Rosa with her dance and choreography background was most valuable. Miguel recruited friend and dancer José Limón who brought his dance company from New York City for the inaugural season in 1950, taught at Bellas Artes, and helped arrange for international exposure of this new Mexican modern dance company. During Miguel's tenure, traditional Mexican dance was not only researched, documented, and preserved but this research into its roots, helped usher in a new era in contemporary Mexican dance.

In 1952, Covarrubias had completely separated from Rolanda in pursuit of one of his students, Rocío Sagaón.[6] He married Sagaón in a Catholic ceremony.[when?][6]

Covarrubias died on 5 February 1957 in Mexico City from sepsis, most likely a complication of his surgery after suffering from an ulcer.[6]

Covarrubias' style was highly influential in America, especially in the 1920s and 1930s, and his artwork and caricatures of influential politicians and artists were featured on the covers of The New Yorker and Vanity Fair.[4]

Covarrubias is also known for his analysis of the pre-Columbian art of Mesoamerica, particularly that of the Olmec culture, and his theory of Mexican cultural diffusion to the north, particularly to the Mississippian Native American Indian cultures. His analysis of iconography presented a strong case that the Olmec predated the Classic Era years before this was confirmed by archaeology. In his thesis on a final cultural battle between Olmecs and Maya, he was encouraged by his friend, the Austrian Surrealist and ethnological philosopher Wolfgang Paalen, who even went so far as to describe the conflict as one of ancient matriarchal culture with new patriarchal orientations in Maya culture with its dominant adoration of the male sun-god Kukulkan. Both Paalen and Covarrubias published their ideas in Paalen's magazine DYN. Covarrubias interest in anthropology went beyond the arts and the Americas—Covarrubias lived in and wrote a thorough ethnography of the "Island of Bali". He shared his appreciation of foreign cultures with the world through his drawings, paintings, writings, and caricatures.

{{cite book}}: |website= ignored (help)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Academics |

|

| Artists |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|