Roquat the Red or Ruggedo of the Rocks, deposed Nome King

Oz character

First appearance

Ozma of Oz (1907)

Last appearance

Handy Mandy in Oz (1937) (canonical)

Created by

Portrayed by

Nicol Williamson (Return to Oz)

Al Snow (Dorothy and the Witches of Oz)

Julian Bleach (Emerald City)

Voiced by

Jason Alexander (Tom and Jerry: Back to Oz)

J. P. Karliak (Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz)

In-universe information

Alias

Roquat the Red

Roquat of the Rocks[1]

Ruggedo of the Rocks

Nickname

The Metal Monarch

Species

Nome

Gender

male

Title

King (former)

Occupation

expatriate wanderer

Nationality

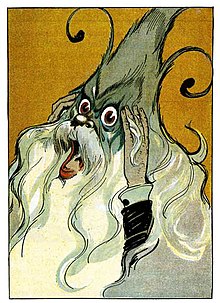

The Nome King is a fictional character created by American author L. Frank Baum. He is introduced in Baum's third Oz book Ozma of Oz (1907). He also appears in many of the continuing sequel Oz novels also written by Baum.[2] Although the character of the Wicked Witch of the West is the most notable and famous Oz villain (due to her appearance in the 1939 MGM musical The Wizard of Oz), it is actually the Nome King who is the most frequent antagonist in the book series.

Katharine M. Rogers, a biographer of L. Frank Baum, has argued that there was a precursor of the Nome King in one of Baum's pre-Oz works. In A New Wonderland (1899), later known as The Magical Monarch of Mo, there is a similar character called King Scowleyow.[3] Rogers finds him a "convincingly evil" villain despite his ridiculous name. His people reportedly live in caves and mines. They dig iron and tin out of the rocks in their environment. They melt these metals into bars and sell them.[3]

Scowleyow hates the King of Phunnyland and all his people, because they live so happily and "care nothing for money.[3] He decides to destroy Phunnyland and instructs his mechanics to build what is essentially a robot. It is described as a great man built of cast iron, and containing within him machinery. The robot is called "the Cast-iron Man".[3] The metallic creature roars, rolls his eyes, and gnashes his teeth. It is set on marching across a valley, destroying trees and houses on its path.[3]

Rogers notes the similarities between Scowleyow and the Nome King: they represent the negation of good will and happiness, they are associated with the underground and material wealth, Scowleyow is a powerful figure who uses his technological knowledge to create a machine capable only of destruction, and both villains demonstrate the tendency of evil towards self-destruction.[3]

The character called the Nome King is originally named Roquat the Red. Later, he takes the name Ruggedo, which Baum first used in a stage adaptation. Even after Ruggedo loses his throne, he continues to think of himself as king and the Oz book authors politely refer to him that way. Authors Ruth Plumly Thompson and John R. Neill used the traditional spelling "gnome" so Ruggedo is the title character in Thompson's The Gnome King of Oz (1927).

In Baum's universe, the Nomes are immortal rock fairies who dwell underground. They hide jewels and precious metals in the earth, and resent the "upstairs people" who dig down for those valuables. Apparently as revenge, the Nome King enjoys keeping surface-dwellers as slaves—not for their labor but simply to have them.

The Nomes' greatest fear are eggs. Upon seeing Billina, Roquat is terrified, declaring that "Eggs are poison to Nomes!" He claims that any Nome who comes in contact with an egg will be weakened to the point that he can be easily destroyed unless he speaks a magic word only known to a few Nomes. Baum, however, strongly hints that the fear of eggs is unjustified, as the Scarecrow repeatedly pelts him with eggs at the end of the novel, causing him no apparent harm beyond stress enough to allow Dorothy Gale to remove his Magic Belt. Sally Roesch Wagner, in her pamphlet The Wonderful Mother of Oz, suggests that Matilda Joslyn Gage had made Baum aware that the egg is an important symbol of matriarchy, and that it is this that the Nomes (among whom no females are seen) actually fear.[4]

In their first encounter with Roquat, in Ozma of Oz (1903), Princess Ozma, Dorothy Gale, and a party from the Emerald City free the royal family of Ev from his enslavement and, for good measure, take away his magic belt.

Roquat becomes so angry that he plots revenge in The Emerald City of Oz (1910). He has his subjects dig a tunnel under the Deadly Desert while his general recruits a host of evil spirits like the Whimsies, the Growleywogs, and the Phanfasms to conquer Oz. Fortunately at the moment of invasion, Ozma wishes (using her magic belt) for a large amount of dust to appear in the tunnel. Roquat and his allies thirstily taste the Water of Oblivion and forget everything where Roquat forgets his enmity and his name.

Tik-Tok of Oz (1914) reintroduces the Nome King with his new name, Ruggedo (all the Nomes, Whimsies, Growleywogs, and Phanfasms having forgotten the old one and old resentments). Using some personal magic, he has enslaved the Shaggy Man's brother, a miner from Colorado. Shaggy, with the help of Betsy Bobbin, the Oogaboo army, some of Dorothy's old friends, and Quox the dragon, conquer the Nome King again and Tititi-Hoochoo the Great Jinjin expels him from his kingdom, placing Chief Steward Kaliko on the throne. In Rinkitink in Oz (1916), Kaliko behaves much like his former master.

InThe Magic of Oz (1919), the exile Ruggedo meets the young enchanter Kiki Aru and plans to destroy Oz again. He gets into the country without Ozma's knowledge, creating havoc. However, he again drinks of the Water of Oblivion, and to stop him ever going bad again Ozma settles him in the Emerald City.

Soon after taking over the Oz series, Ruth Plumly Thompson brought back Ruggedo, his memory and rancor restored and living imprisoned under the city. Finding a box of mixed magic in Kabumpo in Oz (1922), he grows into a giant and runs away with Ozma's royal palace on his head. He is placed on a Runaway Land which runs out to the Nonestic Ocean and strands him on an island.

InThe Gnome King of Oz (1927), he is helped off the island by Peter Brown, an athletic boy from Philadelphia, making his first trip to Oz. As in Ozma of Oz, Ruggedo is quite friendly when he thinks he is going to get his way. After threatening the Emerald City utilizing a Cloak of Invisibility, he is hit with a Silence Stone and immediately struck dumb.

InPirates in Oz (1931), the mute Ruggedo finds a town in the Land of Ev called Menankypoo, whose people speak with words across their foreheads and seek a dumb king. Peter, Pigasus and Captain Samuel Salt aid in his defeat and he is transformed into a jug.

InHandy Mandy in Oz (1937), the Wizard of Wutz, the handsome but cruel King of the Silver Mountain, restored Ruggedo's proper form. At the end of that book, Himself the Elf transforms both of them into cacti, so that they can never make trouble again.

Ruggedo made no further appearances in the original Oz series, but his further adventures have been written in several later books (some of which harmonize with one another; others which are contradictory).

Much fan discussion has revolved around the identity of the Gnome King in Baum's The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus (1902), a jolly rock dweller who does not believe in giving, but only in even exchange. His gnomes watch over the rocks in the Forest of Burzee and make sleigh bells for each of Santa Claus's ten reindeer that he gives in exchange for toys for his children. An editor's note to Judy Pike's article "The Decline and Fall of the Nome King" conjectures that the Gnome King is the Nome King's father.[5]

Concerning the original depiction of the Nome King by L. Frank Baum, essayist Suzanne Rahn has suggested that he was a "distinctly American kind of monarch". Rather than a traditional king, the Nome King was more of an industrial capitalist. His power resided in controlling a monopoly. Ozma's relationship with the Nome Kingdom has been discussed as an example of imperialism in English literature.[6] Rahn compares the king to industrialists Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919), J. P. Morgan (1837-1913), and John D. Rockefeller (1839–1937).[7] Richard Tuerk expands this theory to include the other Nome King, Kaliko. In Rinkitink in Oz (1916), Kaliko says to his allies Queen Cor and King Gos: "as a matter of business policy we powerful Kings must stand together and trample the weaker ones under our feet". In this case, Baum makes his replacement Nome king sound like a stereotypical capitalist from his time period.[7]

According to Jack Zipes, the Gnome King represents materialist greed. He is driven by a lust for power for the sake of power.[8] Once defeated, the King gains a new sinister motivation, revenge. He and his allies want to enslave people to attain wealth and power. Oz is Baum's version of the utopia and the Nome King strives to undermine this utopian civilization.[8]

Zipes believes that Baum was against any kind of violence. In The Emerald City of Oz (1910), the Nome King's invasion of Oz is therefore defeated in a non-violent way. Baum invented a fountain filled with the water of oblivion. A single sip of this water makes the drinker forget everything, including any evil intentions. The would-be invaders of Oz drink from the fountain, forget everything, and return home.[8] Zipes argues that Baum was not going for a message of turning the other cheek. He was aware that if one uses the same methods as one's enemies, one risks becoming like them. If the defenders of Oz became cutthroat and militant like the Nome King and his forces, this would have tarnished the spirit and principles of Oz. So their victory, as orchestrated by Ozma is using a different method, oblivion. The method is creative, humane, and humanitarian.[8]

Gore Vidal argued that Oz represents a "pastoral dream" deriving from the ideals of Thomas Jefferson, though here the slaves have been replaced by magic and good will. The Nome King and his black magic represent a technological civilization, driven by machines and industrialization. Vidal concluded that "the Nome King has governed the United States for more than a century; and he shows no sign of wanting to abdicate."[8]

Zipes believes that Baum was essentially a fairy tale writer. He places him in a group of writers with Charles Dickens (1812–1870), John Ruskin (1819-1900), George MacDonald (1824–1905), and Oscar Wilde (1854–1900). They brought an oppositional political perspective to their fairy tales and questioned the classical fairy tales and society at large. They reached out to young readers from the upper class, the petite bourgeoisie, and the working class. The literary fairy tale was their political weapon and they preached a message of social liberation. In Zipes words': "Their art was a subversive symbolic act intended to illuminate concrete utopias waiting to be realized once the authoritarian rule of the Nome King could be overcome".[8]

Rogers points that The Emerald City of Oz (1910) was supposed to be the finale of the Oz series. Following the end of the Nome King's invasion, Baum announced that the Land of Oz was forever closed from the outside world. The truth was that the writer had become tired of the series. In the preface of Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz (1908), Baum humorously complained that children kept asking him for more Oz tales. He claimed that he knew of many other stories and hoped to tell them as well. In other words, he was ready to move on to other works.[9] This complain also appeared in The Road to Oz (1909), where he hinted at a coming finale to the series.[9]

In this novel, the Nome King has lost all traces of being jolly and good-humored. He has long been stewing over his defeat and the loss of his magic belt. He feels nothing but a constant anger, which has destroyed his own capacity to feel happiness and makes his subjects miserable as well. The King himself points that he is now angry morning, noon, and night. He sees his situation as monotonous and preventing him from gaining any pleasure in life.[9] Rogers observes that the King now resembles any number of historical rulers. He has become an irresponsible tyrant, and is driven only by malice. He also resembles a naughty child given to impotent rages. He starts the book by storming and raving "all by himself". He walks up and down in his jewel-studded cavern and gets angrier all the time. He also turns his anger towards his own subjects, when they disagree with him. He punishes them by throwing them away, though Baum does not really explain the meaning of this punishment. Rogers suggests that it sounds "mysteriously horrible".[9]

Despite Baum's intentions to end the Oz series, he eventually returned to it. He continued writing it from 1912 until his death in 1919. His motivations for returning to it were the readers' continued demand for new stories, his financial need for commercially successful stories, and his own fascination with the world of Oz.[10] In this second period of Oz, Oz becomes a "socialist paradise". The threats to it are genetic experimentation and abuse of magic. The Nome King returns in Tik-Tok of Oz (1914), where he represents cruel oppression.[10]

Jason M. Bell and Jessica Bell trace the slavery and emancipation theme in the Oz tales to Baum's own childhood. As a child, Baum experienced the American Civil War (1861-1865) and the consequent abolition of slavery in the United States. The heroes of the Oz tales tend to be abolitionists and strive to end slavery in any form. The villains are slave owners who seek to enslave others and institute slavery. The inevitable conflict between the two sides is a recurring theme in the Oz tales and has in their view contributed to the enduring popularity of the series.[11] The Bells argue that it is no coincidence that abolitionist Dorothy Gale is from Kansas. Baum was a child during the Bleeding Kansas conflict (1854-1861). Thousands of abolitionists moved to Kansas to vote against slavery, while Border Ruffians from Missouri crossed the borders to stop them.[11] The Nome King is a slave owner and a chauvinist. He is outsmarted and humiliated by Billina the hen, and literally left with egg on his face. The writers find it telling that the hyper-masculine Nomes and their King are terrified of feminine eggs.[11]

The Nome King was first played by Paul de DupontinThe Fairylogue and Radio-Plays (1908). John Dunsmure played Ruggedo, the Metal Monarch in the stage play The Tik-Tok Man of Oz (1913), by Baum, Louis F. Gottschalk, and Victor Schertzinger, produced in Los AngelesbyOliver Morosco. In the play, he sings a duet with Polychrome titled "When in Trouble Come to Papa". As in the novel, the lack of females among Nomes causes Ruggedo to be willing to take her as wife, sister, or daughter so long as she remains to brighten his kingdom, and the song has him trying out the father option.[12]

Over the summer of 2007, South Coast Repertory performed a play called Time Again in Oz, featuring many familiar Oz characters, such as Roquat the Nome King, Tik-Tok, Uncle Henry, and, of course, Dorothy. Instead of being portrayed as an old man that looks like a mineral, Roquat is identified as being tall, rock-like with a boulder-like mass for his torso, and wears a large crown upon his rocky head. He controls the Nomes at will, headed by his lead Nome, Feldspar, who is very similar to Chistery, the flying monkey character from the Broadway adaptation, Wicked.

The Nome King was portrayed on film by Nicol Williamson in 1985's Return to Oz which was based loosely on the books Ozma of Oz and The Marvelous Land of Oz. In that film, his rock-like nature was taken to the extreme via Will Vinton's Claymation. His personality and characterization largely stays true to how he is portrayed in the original novels, being seemingly fair and courteous to Dorothy and her companions under the belief that they will fail a game he sets up for them (in which they touch an ornament from his collection and say "Oz" simultaneously, having three chances each to do so) in order to give them a chance to locate the Scarecrow, whom the Nome King transformed into an ornament shortly after their entering of his domain. Of the group, all but Dorothy fail and are subsequently transformed also. As this occurs, the Nome King progressively becomes more organic looking in appearance, and would have most likely became completely human should Dorothy failed on her last guess (why the Nome King so desires this is never elaborated upon). It is only when she successfully locates the Scarecrow and her friends, subsequently reverting the Nome King to his original form, does he reveal a more sadistic and threatening side to his character (hinted at throughout the film in his earlier exchanges with Princess Mombi and also his Nome Messenger). Hungry for revenge, he grows to an enormous size surrounded in a blaze of fire and tries to eat the protagonists in a scene inspired by Georges Méliès's The Conquest of the Pole (1912). He is eventually destroyed by ingesting the hidden Billina's chicken egg, laid in a panic by the hen (herself hiding in Jack Pumpkinhead's hollow head), since eggs are poisonous to Nomes. In Kansas, his counterpart is Dr. J.B. Worley (also portrayed by Williamson) who is a psychiatrist obsessed with machines and has an interest in electro-therapy. Dorothy was taken to his clinic when she was unable to sleep. By the end of the movie, it was mentioned by Aunt Em that Dr. Worley perished in the fire trying to save his machines.

Roquat, having regained his original name, is the villain of The Oz-Wonderland War, published by DC Comics and starring Captain Carrot and His Amazing Zoo Crew. Much of the story retreads material from Ozma of Oz, as he has also regained the Magic Belt, and it must be seized again. He uses Nomes that parody the Fantastic Four and the Hulk that get pelted by Easter Eggs, again to no apparent harm, as in the book.

Michael G. Ploog, who was a conceptual artist of Return to Oz, wrote and illustrated a graphic novel based on The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus in which the Gnome King looked like the Nome King's likeness in the film, but whose function was greatly expanded from the novel to be the ruler of all the Immortals.

InL. Sprague de Camp's Harold Shea series he teams his protagonist with the Nome King in "Sir Harold and the Gnome King."

InBill Willingham's Vertigo comic book series Fables, the Nome King has sided with the Adversary and is now the ruler of Oz.[13] He is later deposed in an uprising led by former Fabletown resident Bufkin, one of the winged monkeys native to Oz.[14]

In the comic book The Oz/Wonderland Chronicles #1 (2006), Ruggedo is coerced by a new Witch to bring the Jabberwocky creature to life.

In the novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, the Nome King is alluded to once, along with other underground threats believed by the citizens of Wicked's Oz to be mere legend. It is not officially stated whether the Nome King, or other figures undeniably real in Baum's Oz such as Lurline, actually exist in Maguire's Oz.

InBlade: Trinity, Zoe is read the Oz books by her mother and she later compares Drake to the Nome King in that he is bad simply because he has never tried to be good.

InEmerald City Confidential, the Nome King is now a bartender and is mostly reformed (although he is not above using illegal magic to gain back his fortune).

Sherwood Smith's novels The Emerald Wand of Oz and Trouble Under Oz feature Ruggedo's son, Prince Rikiki, who aspires to regain his father's kingdom.

The Nome King appears in Dorothy and the Witches of Oz played by professional wrestler Al Snow. He is among the villains that accompanies the Wicked Witch of the West in her attack on Earth. During the climax of the film, the Nome King fights the Tin Man and is defeated by him.

The Nome King appears in the comic series Fables. He is the current ruler of that land, as well as many of the surrounding kingdoms and Imperial districts. Nome King attended the Imperial conference called after the destruction of the magic grove and was positively delighted by the plans outlined by the Snow Queen for the effective genocide of the mundane population. He did feel, however, that the plan could be improved with his assistance, feeling that he had many minions that could be of great use. In the wake of the fall of the Adversary's Empire, the Nome King creates his own pan-Ozian empire. He was killed during Bufkin's revolution when the Nome King's own hanging rope magically came to life and snapped its master's head off.

The Nome King appears in the season one finale of Emerald City portrayed by Julian Bleach. He appears as a flayed man trapped by Mistress East in the Prison of the Abject, possibly even the first to be imprisoned there. Dorothy Gale frees him in her search of someone able to control the stone giants. He manages to find his skin and puts it back on, before growing bat-like wings and flying to the Emerald City. While his name isn't revealed, it appears he is a form of the so-called "Beast Forever" that the people of Oz are afraid of. The episode ends with Dorothy being called back to Oz to help save it from the Beast Forever. The Beast Forever's identity is revealed in the credits, which list him as "Roquat".

The Nome King appears in Tom and Jerry: Back to Oz voiced by Jason Alexander. He has taken over the Emerald City, captured Glinda and Tuffy, took Glinda's wand, and now he wants to destroy Dorothy and seize her ruby slippers. Since his great fear of the Wizard has kept him underground, Dorothy and her friends journey to Topeka to get the Wizard to return to the Land of Oz and set everything straight. The Nome King is defeated when he falls under the Jitterbug's dancing spell and loses the Ruby Slippers when Tom and Jerry try to keep him from falling into the Pit of Nome Return. His Kansas counterpart is Lucius Bibb who is the neighbor of Aunt Em and Uncle Henry. He files a lawsuit claiming that the twister released some of the Gale pigs who then plundered his prize watermelon patch. He takes the animals away unless Aunt Em, Uncle Henry, and their farmhands can get jobs to get the money to keep their farm animals in twenty-four hours. By the end of the film, Dorothy, Toto, Tom, and Jerry use the potion the Wizard gave them to help pay off Mr. Bibb and have him cancel his lawsuit against the Gale farm where he gets a larger watermelon.

The Nome King appears in Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz portrayed by J. P. Karliak. His plans to take over the Land of Oz and his fear of chickens remain intact with the series.

Thompson

Others

Other books

Characters

Elements

Authors

Illustrators

Related

Films

TV series

Books

Comics

Games

Related