| Pied currawong | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nominate subspecies graculina, Blue Mountains | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Artamidae |

| Genus: | Strepera |

| Species: |

S. graculina

|

| Binomial name | |

| Strepera graculina (Shaw, 1790) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

6 subspecies, see text | |

| |

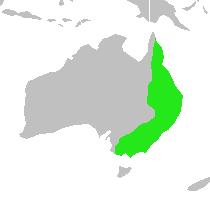

| Pied currawong range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Corvus graculinus G. Shaw, 1790[2] | |

The pied currawong (Strepera graculina) is a black passerine bird native to eastern Australia and Lord Howe Island. One of three currawong species in the genus Strepera, it is closely related to the butcherbirds and Australian magpie of the family Artamidae. Six subspecies are recognised. It is a robust crowlike bird averaging around 48 cm (19 in) in length, black or sooty grey-black in plumage with white undertail and wing patches, yellow irises, and a heavy bill. The male and female are similar in appearance. Known for its melodious calls, the species' name currawong is believed to be of indigenous origin.

Within its range, the pied currawong is generally sedentary, although populations at higher altitudes relocate to lower areas during the cooler months. It is omnivorous, with a diet that includes a wide variety of berries and seeds, invertebrates, bird eggs, juvenile birds and young marsupials. It is a predator which has adapted well to urbanization and can be found in parks and gardens as well as rural woodland. The habitat includes every kind of forested area, although mature forests are preferred for breeding. Roosting, nesting and the bulk of foraging take place in trees, in contrast with the ground-foraging behaviour of its relative, the Australian magpie.

The pied currawong's binomial names were derived from the Latin strepera, meaning "noisy", and graculina for resembling a jackdaw.[10] It was first described by English ornithologist George ShawinJohn White's 1790 book, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, as the "white-vented crow", with Latin name Corvus graculinus.[2] Also published in 1790, John Latham introduced the name Coracias strepera, classifying it with the rollers.[3] The specific epithet strepera (or its masculine form, streperus) was used by several subsequent authors including Leach, Vieillot, Shaw, Temminck, and Gould, in genera Corvus (crows), Cracticus,[7] Gracula (grackles),[4] Barita,[5] and Coronica.[11]

René Lesson defined Strepera as a sub-genus of crows in 1831.[6] John Gould described a second species, the black currawong of Tasmania, in 1836,[12] and the next year created genus Coronica for both species.[8] George Robert Gray adopted Lesson's name Strepera at the genus level and introduced the combination Strepera graculina in 1840.[9][13]

Pied crow-shrike is an old vernacular name from colonial days,[11][14] and the term "pied" refers to two or more colors in blotches. Other common names include pied chillawong, currawang, charawack, kurrawack, tallawong, tullawong, mutton-bird, Otway forester, and pied afternoon-tea bird. The onomatopoeic term currawong itself is derived from the bird's call.[15] However, the exact origin of the term is unclear; the most likely antecedent is the word garrawaŋ from the indigenous Jagera language from the Brisbane region, although the Darug word gurawaruŋ from the Sydney basin is a possibility.[16] Yungang as well as Kurrawang and Kurrawah are names from the Tharawal people of the Illawarra region.[17] French ornithologists such as Daudin, Lesson, and Vieillot called it the réveilleur,[11][18][6][7] meaning 'alarm clock' or 'wake-up caller'.

Its closest relative is the black currawong (S. fuliginosa) of Tasmania, which has sometimes been considered a subspecies.[19] Together with the larger grey currawong (S. versicolor), they form the genus Strepera.[20] Although crow-like in appearance and habits, currawongs are only distantly related to true crows, and instead belong to the family Artamidae, together with the closely related Australian magpie and the butcherbirds. The affinities of all three genera were recognised early on and they were placed in the family Cracticidae in 1914 by ornithologist John Albert Leach after he had studied their musculature.[21] Ornithologists Charles Sibley and Jon Ahlquist recognised the close relationship between woodswallows and butcherbirds in 1985, and combined them into a Cracticini clade,[22] which became the family Artamidae.[20]

Six subspecies are currently recognised, characterised principally by differences in size and plumage. There is a steady change to the birds' morphology and size the further south they are encountered, with lighter and more greyish plumage, larger body size, and a shorter bill. Southerly populations also show more white plumage in the tail, with less whiteness on the wing.[19]

The pied currawong is generally a black bird with white in the wing, undertail coverts, the base of the tail and most visibly, the tip of the tail. It has yellow eyes. Adult birds are 44–50 cm (17–20 in) in length, with an average of around 48 cm (19 in); the wingspan varies from 56 to 77 cm (22 to 30 in), averaging around 69 cm (27 in). Adult males average around 320 g (11 oz), females 280 g (10 oz).[15] The wings are long and broad. The long and heavy bill is about one and a half times as long as the head and is hooked at the end.[36] Juvenile birds have similar markings to adults but have softer and brownish plumage overall, although the white band on the tail is narrower. The upperparts are darker brown with scallops and streaks over the head and neck, and the underparts lighter brown. The eyes are dark brown and the bill dark with a yellow tip. The gape is a prominent yellow.[15] Older birds grow darker until adult plumage is achieved, but juvenile tail markings only change to adult late in development.[15] Birds appear to moult once a year in late summer after breeding.[15] The pied currawong can live for over 20 years in the wild.[37]

Pied currawongs are vocal birds, calling when in flight and at all times of the day. They are noisier early in the morning and in the evening before roosting, as well as before rain.[38] The loud distinctive call has been translated as Kadow-KadangorCurra-wong, akin to a croak. They also have a loud, high-pitched, wolf-like whistle, transcribed as Wheeo.[39] The endemic Lord Howe Island subspecies has a distinct, more melodious call.

The smaller white-winged chough has similar plumage but has red eyes and is found mainly on the ground. Australian crow and raven species have white eyes and lack the white rump, and the similar-sized Australian magpie has red eyes and prominent black and white plumage.[38] The larger grey currawong is readily distinguished by its lighter grey overall plumage and lack of white feathers at the base of the tail.[40] In northwestern Victoria, the black-winged currawong (subspecies melanoptera of the grey) does have a darker plumage than other grey subspecies, but its wings lack the white primaries of the pied currawong.[38]

The pied currawong is common in both wet and dry sclerophyll forests, rural and semi-urban environments throughout eastern Australia, from Cape York Peninsula to western Victoria and Lord Howe Island, where it occurs as an endemic subspecies. It has more recently become prevalent in South-East South Australia, in and around Mount Gambier. It has adapted well to European presence, and has become more common in many areas of eastern Australia, with surveys in Nanango, Queensland, Barham, New South Wales, Geelong, Victoria, as well as the Northern Tablelands and South West Slopes regions in New South Wales, all showing an increase in population. This increase has been most marked, however, in Sydney and Canberra since the 1940s and 1960s, respectively. In both cities, the species had previously been a winter resident only, but now remains year-round and breeds there.[25] They are a dominant species and common inhabitant of Sydney gardens.[41]

In general, the pied currawong is sedentary, although some populations from higher altitudes move to areas of lower elevation in winter.[38] However, evidence for the extent of migration is conflicting, and the species' movements have been little studied to date.[42] More recently still, a survey of the population of pied currawongs in southeastern Queensland between 1980 and 2000 had found the species had become more numerous there, including suburban Brisbane.[43] One 1992 survey reported the total number of pied currawongs in Australia had doubled from three million birds in the 1960s to six million in the early 1990s.[25]

The pied currawong is able to cross bodies of water of some size, as it has been recorded from Rodondo Island, which lies 10 km (6.2 mi) off the coast of Wilsons Promontory in Victoria, as well as some offshore islands in Queensland.[42] It has disappeared from Tryon, North West, Masthead and Heron Islands in the Capricorn Group on the Great Barrier Reef.[44][45] The presence of the Lord Howe subspecies is possibly the result of a chance landing there.[32]

The pied currawong's impact on smaller birds that are vulnerable to nest predation is controversial: several studies have suggested that the species has become a serious problem, but the truth of this widely held perception was queried in a 2001 review of the published literature on their foraging habits by Bayly and Blumstein of Macquarie University, who observed that common introduced birds were more affected than native birds.[46] However, predation by pied currawongs has been a factor in the decline of Gould's petrel at a colony on Cabbage Tree Island, near Port Stephens in New South Wales; currawongs have been reported preying on adult seabirds. Their removal from the islands halted a decline of the threatened petrels.[47] Furthermore, a University of New England study published in 2006 reported that the breeding success rates for the eastern yellow robin (Eopsaltria australis) and scarlet robin (Petroica boodang) on the New England Tablelands were improved after nests were protected and currawongs culled, and some yellow robins even re-colonised an area where they had become locally extinct.[48] The presence of pied currawongs in Sydney gardens is negatively correlated with the presence of silvereyes (Zosterops lateralis).[41]

The species has been implicated in the spread of weeds by consuming and dispersing fruit and seed.[49] In the first half of the twentieth century, pied currawongs were shot as they were considered pests of corn and strawberry crops, as well as assisting in the spread of the prickly pear. They were also shot on Lord Howe Island for attacking chickens. However, they are seen as beneficial in forestry as they consume phasmids, and also in agriculture for eating cocoons of the codling moth.[15]

Pied currawongs are generally tree-dwelling, hunting and foraging some metres above the ground, and thus able to share territory with the ground-foraging Australian magpie. Birds roost in forested areas or large trees at night, disperse to forage in the early morning and return in the late afternoon.[50] Although often solitary or encountered in small groups, the species may form larger flocks of fifty or more birds in autumn and winter. On the ground, a pied currawong hops or struts.[38]

During the breeding season, pied currawongs will pair up and become territorial, defending both nesting and feeding areas. A 1994 study in Sydney's leafy northern suburbs measured an average distance of 250 m (820 ft) between nests,[51] while another in Canberra in 1990 had three pairs in a 400 m (1,300 ft) segment of pine-tree lined street.[52] Territories have been measured around 0.5–0.7 ha in Sydney and Wollongong, although these were restricted to nesting areas and did not include a larger feeding territory, and 7.9 ha in Canberra.[50] Pied currawongs vigorously drive off threats such as ravens, and engage in bill-snapping, dive-bombing and aerial pursuit. They adopt a specific threat display against other currawongs by lowering the head so the head and body are parallel to the ground and pointing the beak out forward, often directly at the intruder.[53] The male predominates in threat displays and territorial defence, and guards the female closely as she builds the nest.[54]

Flocks of birds appear to engage in play; one routine involves a bird perching atop a tall tree, pole or spire, and others swooping, tumbling or diving and attempting to dislodge it. A successful challenger is then challenged in its turn by other birds in the flock.[50]

The pied currawong bathes by wading into water up to 15 cm (5.9 in) deep, squatting down, ducking its head under, and shaking its wings. It preens its plumage afterwards, sometimes applying mud or soil first. The species has also been observed anting.[54]

Although found in many types of woodland, the pied currawong prefers to breed in mature forests.[38] It builds a nest of thin sticks lined with grass and bark high in trees in spring; generally eucalypts are chosen and never isolated ones. It produces a clutch of three eggs; they are a light pinkish-brown colour (likened by one author to that of silly putty) with splotches of darker pink-brown and lavender. Tapered oval in shape, they measure about 30 mm × 42 mm (1.2 in × 1.7 in).[55] The female broods alone.[56] The incubation period is not well known, due to the difficulty of observing nests, but observations indicate around 30 days from laying to hatching. Like all passerines, the chicks are born naked, and blind (altricial), and remain in the nest for an extended period (nidicolous) They quickly grow a layer of ashy-grey down. Both parents feed the young, although the male does not begin to feed them directly until a few days after birth.[56]

The channel-billed cuckoo (Scythrops novaehollandiae) parasitizes pied currawong nests, laying eggs which are then raised by the unsuspecting foster parents.[57] The eggs closely resemble those of the currawong hosts. Pied currawongs have been known to desert nests once cuckoos have visited, abandoning the existing currawong young, which die,[51] and a channel-billed cuckoo has been recorded decapitating a currawong nestling.[53] The brown goshawk (Accipiter fasciatus) and lace monitor (Varanus varius) have also been recorded taking nestlings.[58]

The pied currawong is an omnivorous and opportunistic feeder, eating fruit and berries as well as preying on many invertebrates, and smaller vertebrates, mostly juvenile birds and bird eggs, although they may take healthy adult birds up to the size of a crested pigeon on occasion. Currawongs will hunt in trees, snatching insects and berries, as well as birds and eggs from nests. They also hunt in the air and on the ground.[37] Insects predominate in the diet during summer months, and fruit during the winter. They will often scavenge, eating scraps and rubbish and can be quite bold when seeking food from people, lingering around picnic areas and bird-feeding trays.[59] Beetles and ants are the most common types of insects consumed. Pied currawongs have been recorded taking mice, as well as chickens and turkeys from farms.[60] The pied currawong consumes fruit, including a wide variety of figs, such as the Moreton Bay (Ficus macrophylla), Port Jackson (F. rubiginosa), Banyan (F. virens) and Strangler fig (F. watkinsiana),[61] as well as lillypillies (Syzygium species), white cedar (Melia azedarach), plum pine (Podocarpus elatus), and geebungs (Persoonia species). Other fruit is also sought after, and currawongs have been known to raid orchards, eating apples, pears, strawberries, grapes, stone fruit, citrus, and corn.[49] Pied currawongs have been responsible for the spread of the invasive ornamental Asparagus aethiopicus (often called A. densiflorus) in the Sydney area,[62] the weedy privet species Ligustrum lucidum and L. sinense, and firethorn species Pyracantha angustifolia and P. rogersiana around Armidale.[49]

Birds forage singly or in pairs in summer, and more often in larger flocks in autumn and winter, during which time they are more likely to loiter around people and urban areas.[59] They occasionally associate with Australian magpies (Gymnorhina tibicen) or common starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) when foraging.[60] Birds have also been encountered with grey currawongs (S. versicolor) and satin bowerbirds (Ptilinorhynchus violaceus).[38] The species has been reported stealing food from other birds such as the Australian hobby (Falco longipennis),[63] collared sparrowhawk (Accipiter cirrocephalus), and sulphur-crested cockatoo (Cacatua galerita).[64] Pied currawongs will also harass each other.[49] A 2007 study conducted by researchers from the Australian National University showed that white-browed scrubwren (Sericornis frontalis) nestlings became silent when they heard the recorded sound of a pied currawong walking through leaf litter.[65]

The range size criterion does not apply to this species because it has such a large range. As a result, it does not approach the vulnerable thresholds. The population trend appears to be increasing and its size has not been quantified, but it does not appear to be close to the susceptible thresholds under the population size criterion (10,000 mature individuals with a continuing decline estimated to be >10 percent in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). As a result, the species is considered to be least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.[1]

In Mr. White's Voyage, above referred to, I have considered this bird as a species of Corvus; but am at present inclined to think it more properly a species of Gracula.

| Strepera graculina |

|

|---|---|

| Corvus graculinus |

|