Psychedelic art (also known as psychedelia) is art, graphics or visual displays related to or inspired by psychedelic experiences and hallucinations known to follow the ingestion of psychedelic drugs such as LSD, psilocybin, and DMT. The word "psychedelic" (coined by British psychologist Humphry Osmond) means "mind manifesting". By that definition, all artistic efforts to depict the inner world of the psyche may be considered "psychedelic".

In common parlance "psychedelic art" refers above all to the art movement of the late 1960s counterculture, featuring highly distorted or surreal visuals, bright colors and full spectrums and animation (including cartoons) to evoke, convey, or enhance psychedelic experiences. Psychedelic visual arts were a counterpart to psychedelic rock music. Concert posters, album covers, liquid light shows, liquid light art, murals, comic books, underground newspapers and more reflected not only the kaleidoscopically swirling colour patterns of psychedelic hallucinations, but also revolutionary political, social and spiritual sentiments inspired by insights derived from these psychedelic states of consciousness.

Psychedelic art is informed by the notion that altered states of consciousness produced by psychedelic drugs are a source of artistic inspiration. The psychedelic art movement is similar to the surrealist movement in that it prescribes a mechanism for obtaining inspiration. Whereas the mechanism for surrealism is the observance of dreams, a psychedelic artist turns to drug induced hallucinations. Both movements have strong ties to important developments in science. Whereas the surrealist was fascinated by Freud's theory of the unconscious, the psychedelic artist has been literally "turned on" by Albert Hofmann's discovery of LSD.

Among the work forerunners of psychedelic art, the following authors and artists can be noted: Lautreamont, Louis-Ferdinand Celine, Stanislav Witkevich, Antonin Artaud, Georges Bataille, William Burroughs, De Quincey, Terence McKenna, Carlos Castaneda. Mikhail Bulgakov is the first writer to describe narcotic hallucinations. In particular, art researchers Tim Lapetino and James Orok trace the connection of psychedelic art with Dadaism, Surrealism, Lettrism, and Situationism.[1][2]

The early examples of "psychedelic art" are literary rather than visual, although there are some examples in the Surrealist art movement, such as Remedios Varo and André Masson. Other early examples include Antonin Artaud who writes of his peyote experience in Voyage to the Land of the Tarahumara (1937) and Henri Michaux who wrote Misérable Miracle (1956), to describe his experiments with mescaline and hashish.

Aldous Huxley's The Doors of Perception (1954) and Heaven and Hell (1956) remain definitive statements on the psychedelic experience.

Albert Hofmann and his colleagues at Sandoz Laboratories were convinced immediately after its discovery in 1943 of the power and promise of LSD. For two decades following its discovery LSD was marketed by Sandoz as an important drug for psychological and neurological research. Hofmann saw the drug's potential for poets and artists as well, and took great interest in the German writer Ernst Jünger's psychedelic experiments.

Early artistic experimentation with LSD was conducted in a clinical context by Los Angeles–based psychiatrist Oscar Janiger. Janiger asked a group of 50 different artists to each do a painting from life of a subject of the artist's choosing. They were subsequently asked to do the same painting while under the influence of LSD. The two paintings were compared by Janiger and also the artist. The artists almost unanimously reported LSD to be an enhancement to their creativity.

Ultimately it seems that psychedelics would be most warmly embraced by the American counterculture. Beatnik poets Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs became fascinated by psychedelic drugs as early as the 1950s as evidenced by The Yage Letters (1963). The Beatniks recognized the role of psychedelics as sacred inebriants in Native American religious ritual, and also had an understanding of the philosophy of the surrealist and symbolist poets who called for a "complete disorientation of the senses" (to paraphrase Arthur Rimbaud). They knew that altered states of consciousness played a role in Eastern Mysticism. They were hip to psychedelics as psychiatric medicine. LSD was the perfect catalyst to electrify the eclectic mix of ideas assembled by the Beats into a cathartic, mass-distributed panacea for the soul of the succeeding generation.

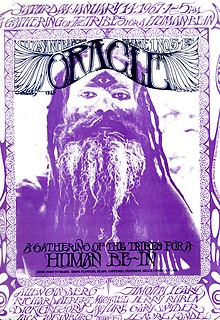

Leading proponents of the 1960s psychedelic art movement were San Francisco poster artists such as: Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Bonnie MacLean, Stanley Mouse & Alton Kelley, Bob Masse, and Wes Wilson. Their psychedelic rock concert posters were inspired by Art Nouveau, Victoriana, Dada, and Pop Art. The "Fillmore Posters" were among the most notable of the time. Richly saturated colors in glaring contrast, elaborately ornate lettering, strongly symmetrical composition, collage elements, rubber-like distortions, and bizarre iconography are all hallmarks of the San Francisco psychedelic poster art style. The style flourished from about 1966 to 1972. Their work was immediately influential to vinyl record album cover art, and indeed all of the aforementioned artists also created album covers.

Although San Francisco remained the hub of psychedelic art into the early 1970s, the style also developed internationally: British artist Bridget Riley became famous for her Op art paintings of psychedelic patterns creating optical illusions. Mati Klarwein created psychedelic masterpieces for Miles Davis' Jazz-Rock fusion albums, and also for Carlos Santana's Latin rock. Pink Floyd worked extensively with London-based designers, Hipgnosis to create graphics to support the concepts in their albums. Willem de Ridder created cover art for Van Morrison. Los Angeles area artists such as John Van Hamersveld, Warren Dayton and Art Bevacqua and New York artists Peter Max and Milton Glaser all produced posters for concerts or social commentary (such as the anti-war movement) that were highly collected during this time. Life Magazine's cover and lead article for the September 1, 1967 issue at the height of the Summer of Love focused on the explosion of psychedelic art on posters and the artists as leaders in the hippie counterculture community.

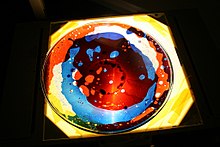

Psychedelic light-shows were a new art-form developed for rock concerts. Using oil and dye in an emulsion that was set between large convex lenses upon overhead projectors the lightshow artists created bubbling liquid visuals that pulsed in rhythm to the music. This was mixed with slideshows and film loops to create an improvisational motion picture art form to give visual representation to the improvisational jams of the rock bands and create a completely "trippy" atmosphere for the audience. The Brotherhood of Light were responsible for many of the light-shows in San Francisco psychedelic rock concerts.

Out of the psychedelic counterculture also arose a new genre of comic books: underground comix. "Zap Comix" was among the original underground comics, and featured the work of Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, Victor Moscoso, Rick Griffin, and Robert Williams among others. Underground Comix were ribald, intensely satirical, and seemed to pursue weirdness for the sake of weirdness. Gilbert Shelton created perhaps the most enduring of underground cartoon characters, "The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers", whose drugged out exploits held a hilarious mirror up to the hippy lifestyle of the 1960s.

Psychedelic art was also applied to the LSD itself. LSD began to be put on blotter paper in the early 1970s and this gave rise to blotter art, a specialized art form of decorating the blotter paper. Often the blotter paper was decorated with tiny insignia on each perforated square tab, but by the 1990s this had progressed to complete four color designs often involving an entire page of 900 or more tabs. Mark McCloud is a recognized authority on the history of LSD blotter art.

By the late 1960s, the commercial potential of psychedelic art had become hard to ignore. General Electric, for instance, promoted clocks with designs by New York artist Peter Max. A caption explains that each of Max's clocks "transposes time into multi-fantasy colors."[3] In this and many other corporate advertisements of the late 1960s featuring psychedelic themes, the psychedelic product was often kept at arm's length from the corporate image: while advertisements may have reflected the swirls and colors of an LSD trip, the black-and-white company logo maintained a healthy visual distance. Several companies, however, more explicitly associated themselves with psychedelica: CBS, Neiman Marcus, and NBC all featured thoroughly psychedelic advertisements between 1968 and 1969.[4] In 1968, Campbell's soup ran a poster promotion that promised to "Turn your wall souper-delic!"[5]

The early years of the 1970s saw advertisers using psychedelic art to sell a limitless array of consumer goods. Hair products, cars, cigarettes, and even pantyhose became colorful acts of pseudo-rebellion.[6] The Chelsea National Bank commissioned a psychedelic landscape by Peter Max, and neon green, pink, and blue monkeys inhabited advertisements for a zoo.[7] A fantasy land of colorful, swirling, psychedelic bubbles provided the perfect backdrop for a Clearasil ad.[8] As Brian Wells explains, "The psychedelic movement has, through the work of artists, designers, and writers, achieved an astonishing degree of cultural diffusion… but, though a great deal of diffusion has taken place, so, too, has a great deal of dilution and distortion."[9] Even the term "psychedelic" itself underwent a semantic shift, and soon came to mean "anything in youth culture which is colorful, or unusual, or fashionable."[10] Puns using the concept of "tripping" abounded: as an advertisement for London Britches declared, their product was "great on trips!"[11] By the mid-1970s, the psychedelic art movement had been largely co-opted by mainstream commercial forces, incorporated into the very system of capitalism that the hippies had struggled so hard to change.

Examples of other psychedelic art material are tapestry, blacklight posters printed with fluorescent ink against backgrounds of velvet black which are intended for display under an ultraviolet lamp which causes the colors to glow in the dark, paisley printed cloths, tie-dyed or batiked curtains and stickers with designs and slogans written in loopy, art nouveau-like fonts,[12] clothing,[13] canvas and other printed artefacts[14] and furniture.[15]

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this articlebyadding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Psychedelic art" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Computer art has allowed for an even greater and more profuse expression of psychedelic vision. Fractal generating software gives an accurate depiction of psychedelic hallucinatory patterns, but even more importantly 2D and 3D graphics software allow for unparalleled freedom of image manipulation. Much of the graphics software seems to permit a direct translation of the psychedelic vision. The "digital revolution" was indeed heralded early on as the "New LSD" by none other than Timothy Leary.[16][17]

The rave movement of the 1990s was a psychedelic renaissance fueled by the advent of newly available digital technologies. The rave movement developed a new graphic art style partially influenced by 1960s psychedelic poster art, but also strongly influenced by graffiti art, and by 1970s advertising art, yet clearly defined by what digital art and computer graphics software and home computers had to offer at the time of creation. Conversely, the convolutional neural network DeepDream finds and enhances patterns in images purely via algorithmic pareidolia.

Concurrent to the rave movement, and in key respects integral to it, are the development of new mind-altering drugs, most notably, MDMA (Ecstasy). Ecstasy, like LSD, has had a tangible influence on culture and aesthetics, particularly the aesthetics of rave culture. But MDMA is (arguably) not a real psychedelic, but is described by psychologists as an entactogen. Development of new psychedelics such as 2C-B and related compounds (developed primarily by chemist Alexander Shulgin) which are truly psychedelic has provided a fertile ground for artistic exploration since many of the new psychedelics possess their own unique properties that will affect the artist's vision accordingly.

Even as fashions have changed, and art and culture movements have come and gone, certain artists have steadfastly devoted themselves to psychedelia. Well-known examples are Amanda Sage, Alex Grey, and Robert Venosa. These artists have developed unique and distinct styles that while containing elements that are "psychedelic", are clearly artistic expressions that transcend simple categorization. While it is not necessary to use psychedelics to arrive at such a stage of artistic development, serious psychedelic artists are demonstrating that there is tangible technique to obtaining visions, and that technique is the creative use of psychedelic drugs.

This section possibly contains original research. Please improve itbyverifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (February 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

|

| |

|---|---|

| Arts |

|

| Cultural events |

|

| Social and political movements |

|

| Media |

|

| Subcultures |

|