Pyotr Kapitsa

| |

|---|---|

| Пётр Капица | |

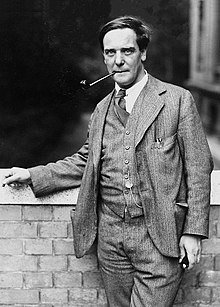

Kapitsa in the 1930s

| |

| Born | Pyotr Leonidovich Kapitsa (1894-07-09)9 July 1894 |

| Died | 8 April 1984(1984-04-08) (aged 89) |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow |

| Citizenship | USSR |

| Known for | Superfluidity Kapitza instability Kapitza number Kapitza resistance Kapitza's pendulum Kapitsa–Dirac effect |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | Moscow State University |

| Doctoral advisor | Abram Ioffe |

| Doctoral students | David Shoenberg |

Pyotr Leonidovich KapitsaorPeter Kapitza FRS (Russian: Пётр Леонидович Капица, Romanian: Petre Capița; 9 July [O.S. 26 June] 1894[2] – 8 April 1984) was a leading Soviet physicist and Nobel laureate,[3][4] whose research focused on low-temperature physics.

Kapitsa was born in Kronstadt, Russian Empire, to the Bessarabian Leonid Petrovich Kapitsa (Romanian: Leonid Petrovici Capița), a military engineer who constructed fortifications, and to the Volhynian Olga Ieronimovna Kapitsa, from a noble Polish Stebnicki family.[5][6] Besides Russian, the Kapitsa family also spoke Romanian.[7]

Kapitsa's studies were interrupted by the First World War, in which he served as an ambulance driver for two years on the Polish front.[8] He graduated from the Petrograd Polytechnical Institute in 1918. His wife and two children died in the flu epidemic of 1918–19. He subsequently studied in Britain, working for over ten years with Ernest Rutherford in the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge, and founding the influential Kapitza club. He was the first director (1930–34) of the Mond Laboratory in Cambridge.[9]

In the 1920s he originated techniques for creating ultrastrong magnetic fields by injecting high current for brief periods into specially constructed air-core electromagnets. In 1928 he discovered the linear relation between resistivity and magnetic field strength in various metals under very strong magnetic fields.[3]

In 1934, Kapitsa returned to Russia to visit his parents but the Soviet Union prevented him from travelling back to Great Britain.[10]

As his equipment for high-magnetic field research remained in Cambridge (although later Ernest Rutherford negotiated with the British government the possibility of shipping it to the USSR), he changed the direction of his research to the study of low temperature phenomena, beginning with a critical analysis of the existing methods for achieving low temperatures. In 1934 he developed new and original apparatus (based on the adiabatic principle) for making significant quantities of liquid helium.[citation needed]

Kapitsa formed the Institute for Physical Problems, in part using equipment which the Soviet government bought from the Mond Laboratory in Cambridge (with the assistance of Rutherford, once it was clear that Kapitsa would not be permitted to return).[citation needed]

In Russia, Kapitsa began a series of experiments to study liquid helium. This research culminated with the 1937 discovery of superfluidity (another expression of the state of matter that gives rise to superconductivity). Beginning with a letter to the editor of Science on 8 January 1938 where he reported the absence of measurable viscosity in liquid helium-4 cooled below 1.8 K, Kapitza documented the properties of helium-4 superfluid in a series of papers. This was the body of work for which he was later awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, "basic inventions and discoveries in the area of low-temperature physics".[11]

In 1939, he developed a new method for liquefaction of air with a low-pressure cycle using a special high-efficiency expansion turbine. Consequently, during World War II he was assigned to head the Department of Oxygen Industry attached to the USSR Council of Ministers, where he developed his low-pressure expansion techniques for industrial purposes. He invented high power microwave generators (1950–1955) and discovered a new kind of continuous high pressure plasma discharge with electron temperatures over 1,000,000 K.[citation needed]

In November 1945, Kapitsa quarreled with Lavrentiy Beria, head of the NKVD and in charge of the Soviet atomic bomb project, writing to Joseph Stalin about Beria's ignorance of physics and his arrogance. Stalin backed Kapitsa, telling Beria he had to cooperate with the scientists. Kapitsa refused to meet Beria: "If you want to speak to me, then come to the Institute." Stalin offered to meet Kapitsa, but this never happened.[12]

Immediately after the war, a group of prominent Soviet scientists (including Kapitsa in particular) lobbied the government to create a new technical university, the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology. Kapitsa taught there for many years. From 1957, he was also a member of the presidium of the Soviet Academy of Sciences and at his death in 1984 was the only presidium member who was not also a member of the Communist Party.[13]

In 1966, Kapitsa was allowed to visit Cambridge to receive the Rutherford Medal and Prize.[14] While dining at his old college, Trinity, he found he did not have the required gown. He asked to borrow one, but a college servant asked him when he last dined at high table, "Thirty-two years" replied Kapitza. Within moments the servant returned, not with any gown, but Kapitsa's own.[15]

In 1978, Kapitsa won the Nobel Prize in Physics "for his basic inventions and discoveries in the area of low-temperature physics" and was also cited for his long term role as a leader in the development of this area. He shared the prize with Arno Allan Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson, who won for discovering the cosmic microwave background.[16]

Kapitsa resistance is the thermal resistance (which causes a temperature discontinuity) at the interface between liquid helium and a solid. The Kapitsa–Dirac effect is a quantum mechanical effect consisting of the diffraction of electrons by a standing wave of light. In fluid dynamics, the Kapitza number is a dimensionless number characterizing the flow of thin films of fluid down an incline.

Pyotr Kapitsa had the nickname "Centaurus". This arose when once Artem Alikhanian asked Kapitsas' student Shalnikov "is your supervisor a human or a beast?" to which Shalnikov responded that he is a Centaurus, i.e. he can be human but also he can get angry and hit you with hooves like a horse.[17] Kapitsa was married in 1927 to Anna Alekseyevna Krylova (1903-1996), daughter of applied mathematician Aleksey Krylov. They had two sons, Sergey and Andrey. Sergey Kapitsa (1928–2012) was a physicist and demographer. Kapitsa was also the host of the popular and long-running Russian scientific TV show Evident, but Incredible.[18] Andrey Kapitsa (1931–2011) was a geographer. He was credited with the discovery and naming of Lake Vostok, the largest subglacial lakeinAntarctica, which lies 4,000 meters below the continent's ice cap.[19]

Kapitsa had the ear of people high up in the Soviet government, due to the usefulness to industry of his discoveries, regularly writing letters on matters of science policy. In particular, he saved both Vladimir Fock and Lev Landau from Stalin's purges of the 1930s, telling Vyacheslav Molotov that Landau was the only one who would be able to solve an important physics puzzle of the time.[20]

Kapitsa died on 8 April 1984 in Moscow at the age 89.

Aminor planet, 3437 Kapitsa, discovered by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Karachkina in 1982, is named after him.[21] He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1929.[1] In 1958 he was elected a Member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina.[22]

|

1978 Nobel Prize laureates

| |

|---|---|

| Chemistry |

|

| Literature (1978) |

|

| Peace |

|

| Physics |

|

| Physiology or Medicine |

|

| Economic Sciences |

|

| |

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Academics |

|

| Artists |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|