|

| Part of a series on the |

| Canon law of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

Ius vigens (current law) |

|

Jus novum (c. 1140-1563) Jus novissimum (c. 1563-1918) Jus codicis (1918-present) Other |

|

|

|

Liturgical law |

|

Sacred places

Sacred times |

|

|

Supreme authority, particular churches, and canonical structures

Supreme authority of the Church

Supra-diocesan/eparchal structures

|

|

Philosophy, theology, and fundamental theory of Catholic canon law |

|

Temporal goods (property) |

|

Law of persons Clerics

Office Consecrated life |

|

Canonical documents |

|

Penal law |

|

Procedural law

Pars statica (tribunals & ministers/parties)

Pars dynamica (trial procedure)

Election of the Roman Pontiff |

|

Legal practice and scholarship Academic degrees Journals and Professional Societies Faculties of canon law Canonists |

|

Law of consecrated life |

|

|

|

|

Simony (/ˈsɪməni/) is the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things. It is named after Simon Magus,[1] who is described in the Acts of the Apostles as having offered two disciples of Jesus payment in exchange for their empowering him to impart the power of the Holy Spirit to anyone on whom he would place his hands.[2] The term extends to other forms of trafficking for money in "spiritual things".[3][4]

The earliest church legislation against simony may be that of the forty-eighth canon of the Synod of Elvira (c. 305), against the practice of making a donation following a baptism.[5]: 60

Following the Edict of Milan (313), the increased power and wealth of the church hierarchy attracted simony.[5]: 30 There are several accusations of simony (not by that name) against Arians, from Athanasius of Alexandria, Hilary of Poitiers, Pope Liberius and Gregory of Nazianzus.[5]: 34–36 Many Church Fathers spoke out against the selling of ministries, such as Ambrose.[5]: 56

Anti-simony provisions in Church Council canons (and papal bulls) became common: the First Council of Nicaea, the Synod of Antioch (341), and the Councils of Serdica (343–344), Chalcedon, and Orléans (533), etc.[5]: 62, 66, 121

The purchase or sale of ecclesiastical office was associated with the figure of Simon Magus in the Acts of the Apostles,[2] and the name started to be used as a term. Key in popularizing the term was Pope Gregory I (590-604), who labelled such exchanges as the "simoniac heresy".[6]

Although considered a serious offense against canon law, simony is thought to have become widespread in the Catholic Church during the 9th and 10th centuries.[7] In the eleventh century, it was the focus of a great deal of debate.[8] Central to this debate was the validity of simoniacal orders: that is, whether a cleric who had obtained their office through simony was validly ordained.[9]

The Corpus Juris Canonici, the Decretum[10] and the Decretals of Gregory IX[11] all dealt with the subject. The offender, whether simoniacus (the perpetrator of a simoniacal transaction) or simoniace promotus (the beneficiary of a simoniacal transaction), was liable to deprivation of his benefice and deposition from orders if a secular priest, or to confinement in a stricter monastery if a regular. No distinction seems to have been drawn between the sale of an immediate and of a reversionary interest. The innocent simoniace promotus was, apart from dispensation, liable to the same penalties as though he were guilty.[12][clarification needed]

In 1494, a member of the Carmelite order, Adam of Genoa, was found murdered in his bed with twenty wounds after preaching against the practice of simony.[13]

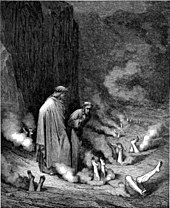

In the 14th century, Dante Alighieri depicted the punishment of many "clergymen, and popes and cardinals" in hell for being avaricious or miserly.[14]

He also criticised certain popes and other simoniacs:[15]

Rapacious ones, who take the things of God,

that ought to be the brides of Righteousness,

and make them fornicate for gold and silver!

The time has come to let the trumpet sound

for you; ...

Simony remains prohibited in Roman Catholic canon law. In the Code of Canon Law, Canon 149.3 notes that "Provision of an office made as a result of simony is invalid by the law itself."[16]

The Church of England struggled with the practice after its separation from Rome. For the purposes of English law, simony is defined by William Blackstone as "obtain[ing] orders, or a licence to preach, by money or corrupt practices"[17] or, more narrowly, "the corrupt presentation of any one to an ecclesiastical benefice for gift or reward".[18] While English law recognized simony as an offence,[19] it treated it as merely an ecclesiastical matter, rather than a crime, for which the punishment was forfeiture of the office or any advantage from the offence and severance of any patronage relationship with the person who bestowed the office. Both Edward VI and Elizabeth I promulgated statutes against simony, in the latter case through the Simony Act 1588 (31 Eliz. 1. c. 6). The cases of Bishop of St. David's Thomas Watson in 1699[20] and of Dean of York William Cockburn in 1841 were particularly notable.[21]

By the Benefices Act 1892,[which?] a person guilty of simony is guilty of an offence for which he may be proceeded against under the Clergy Discipline Act 1892 (55 & 56 Vict. c. 32). An innocent clerk is under no disability, as he might be by the canon law. Simony may be committed in three ways – in promotion to orders, in presentation to a benefice, and in resignation of a benefice. The common law (with which the canon law is incorporated, as far as it is not contrary to the common or statute law or the prerogative of the Crown) has been considerably modified by statute. Where no statute applies to the case, the doctrines of the canon law may still be of authority.[12]

As of 2011[update], simony remains an offence.[22] An unlawfully bestowed office can be declared void by the Crown, and the offender can be disabled from making future appointments and fined up to £1,000.[23] Clergy are no longer required to make a declaration as to simony on ordination, but offences are now likely to be dealt with under the Clergy Discipline Measure 2003 (No. 3).[24][full citation needed][25]

Attribution: