Soyuz MS-20 approaching the ISS

| |||

| Manufacturer | Energia | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country of origin | Russia | ||

| Operator | Roscosmos | ||

| Specifications | |||

| Spacecraft type | Crewed spaceflight | ||

| Launch mass | 7,080 kg (15,610 lb) | ||

| Crew capacity | 3 | ||

| Volume | 10.5 m3 (370 cu ft) | ||

| Batteries | 755 Ah | ||

| Regime | Low Earth orbit | ||

| Design life | 210 days when docked to International Space Station (ISS) | ||

| Dimensions | |||

| Solar array span |

| ||

| Width | 2.72 m (8 ft 11 in) | ||

| Production | |||

| Status | Active | ||

| Built | 24 | ||

| Launched | 24 (as of 15 Sep 2023) | ||

| Operational | 2 | ||

| Retired | 22 (not including MS-10) | ||

| Failed | 1 (Soyuz MS-10) | ||

| Maiden launch | Soyuz MS-01 (7 July 2016) | ||

| Last launch | Active | ||

| Related spacecraft | |||

| Derived from | Soyuz TMA-M | ||

| |||

The Soyuz MS (Russian: Союз МС; GRAU: 11F732A48) is a revision of the Russian spacecraft series Soyuz first launched in 2016. It is an evolution of the Soyuz TMA-M spacecraft, with modernization mostly concentrated on the communications and navigation subsystems. It is used by Roscosmos for human spaceflight. The Soyuz MS has minimal external changes with respect to the Soyuz TMA-M, mostly limited to antennas and sensors, as well as the thruster placement.[2]

The first launch was Soyuz MS-01 on 7 July 2016, aboard a Soyuz-FG launch vehicle towards the International Space Station (ISS).[3] The trip included a two-day checkout phase for the design before docking with the ISS on 9 July 2016.[4]

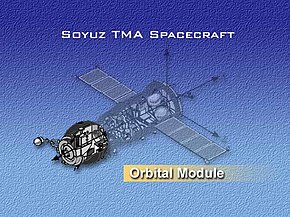

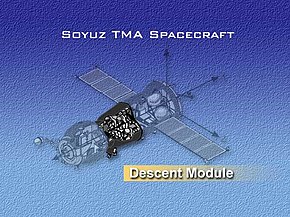

A Soyuz spacecraft consists of three parts (from front to back):

The first two portions are habitable living space. By moving as much as possible into the orbital module, which does not have to be shielded or decelerated during re-entry, the Soyuz three-part craft is both larger and lighter than the two-part Apollo spacecraft's command module. The Apollo command module had six cubic meters of living space and a mass of 5000 kg; the three-part Soyuz provided the same crew with nine cubic meters of living space, an airlock, and a service module for the mass of the Apollo capsule alone. This does not take into consideration the orbital module that could be used in place of the LM in Apollo.

Soyuz can carry up to three cosmonauts and provide life support for them for about 30 person-days. The life support system provides a nitrogen/oxygen atmosphere at sea level partial pressures. The atmosphere is regenerated through KO2 cylinders, which absorb most of the CO2 and water produced by the crew and regenerates the oxygen, and LiOH cylinders which absorb leftover CO2. Estimated deliverable payload weight is up to 200 kg and up to 65 kg can be returned.[5]

The vehicle is protected during launch by a nose fairing, which is jettisoned after passing through the atmosphere. It has an automatic docking system. The spacecraft can be operated automatically, or by a pilot independently of ground control.

The forepart of the spacecraft is the orbital module ((in Russian): бытовой отсек (БО), Bitovoy otsek (BO)) also known as the Habitation section. It houses all the equipment that is not needed for reentry, such as experiments, cameras or cargo. Commonly, it is used as both eating area and lavatory. At its far end, it also contains the docking port. This module also contains a toilet, docking avionics and communications gear. On the latest Soyuz versions, a small window was introduced, providing the crew with a forward view.

A hatch between it and the descent module can be closed so as to isolate it to act as an airlock if needed with cosmonauts exiting through its side port (at the bottom of this picture, near the descent module). On the launch pad, cosmonauts enter the spacecraft through this port.

This separation also lets the orbital module be customized to the mission with less risk to the life-critical descent module. The convention of orientation in zero gravity differs from that of the descent module, as cosmonauts stand or sit with their heads to the docking port.

The reentry module ((in Russian): спускаемый аппарат (СА), Spuskaemiy apparat (SA)) is used for launch and the journey back to Earth. It is covered by a heat-resistant covering to protect it during re-entry. It is slowed initially by the atmosphere, then by a braking parachute, followed by the main parachute which slows the craft for landing. At one meter above the ground, solid-fuel braking engines mounted behind the heat shield are fired to give a soft landing. One of the design requirements for the reentry module was for it to have the highest possible volumetric efficiency (internal volume divided by hull area). The best shape for this is a sphere, but such a shape can provide no lift, which results in a purely ballistic reentry. Ballistic reentries are hard on the occupants due to high deceleration and can't be steered beyond their initial deorbit burn. That is why it was decided to go with the "headlight" shape that the Soyuz uses — a hemispherical forward area joined by a barely angled conical section (seven degrees) to a classic spherical section heat shield. This shape allows a small amount of lift to be generated due to the unequal weight distribution. The nickname was coined at a time when nearly every automobile headlight was a circular paraboloid.

At the back of the vehicle is the service module ((in Russian): приборно-агрегатный отсек (ПАО), Priborno-Agregatniy Otsek (PAO)). It has an instrumentation compartment ((in Russian): приборный отсек (ПО), Priborniy Otsek (PO)), a pressurized container shaped like a bulging can that contains systems for temperature control, electric power supply, long-range radio communications, radio telemetry, and instruments for orientation and control. The propulsion compartment ((in Russian): агрегатный отсек (АО), Agregatniy Otsek (AO)), a non-pressurized part of the service module, contains the main engine and a spare: liquid-fuel propulsion systems for maneuvering in orbit and initiating the descent back to Earth. The spacecraft also has a system of low-thrust engines for orientation, attached to the intermediate compartment ((in Russian): переходной отсек (ПхО), Perekhodnoi Otsek (PkhO)). Outside the service module are the sensors for the orientation system and the solar array, which is oriented towards the sun by rotating the spacecraft.

Because its modular construction differs from that of previous designs, the Soyuz has an unusual sequence of events prior to re-entry. The spacecraft is turned engine-forward and the main engine is fired for de-orbiting fully 180° ahead of its planned landing site. This requires the least propellant for re-entry, the spacecraft traveling on an elliptical Hohmann orbit to a point where it will be low enough in the atmosphere to re-enter.

Early Soyuz spacecraft would then have the service and orbital modules detach simultaneously. As they are connected by tubing and electrical cables to the descent module, this would aid in their separation and avoid having the descent module alter its orientation. Later Soyuz spacecraft detach the orbital module before firing the main engine, which saves even more propellant, enabling the descent module to return more payload. The orbital module cannot remain in orbit as an addition to a space station as the hatch enabling it to function as an airlock is part of the descent module.

Re-entry firing is typically done on the "dawn" side of the Earth, so that the spacecraft can be seen by recovery helicopters as it descends in the evening twilight, illuminated by the sun when it is above the shadow of the Earth. Since the beginning of Soyuz missions to the ISS, only five have performed nighttime landings.[6]

The Soyuz MS received the following upgrades with respect to the Soyuz TMA-M:[7]

Soyuz MS flights will continue until at least Soyuz MS-23, with regular crew rotation Soyuz flights being reduced from four a year to two a year with the introduction of Commercial Crew (CCP) flights contracted by NASA. Starting from 2021, Roscosmos is marketing the spacecraft for dedicated commercial missions ranging from ~10 days to six months. Currently, Roscosmos has three such flights booked, Soyuz MS-20 in 2021 and Soyuz MS-23 in 2022, plus a currently unnumbered flight scheduled for 2023.[20][21][22]

| Mission | Crew | Notes | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed | |||

| Soyuz MS-01 | Delivered Expedition 48/49 crew to ISS. Originally scheduled to ferry the ISS-47/48 crew to ISS, although switched with Soyuz TMA-20M due to delays.[23] | 115 days | |

| Soyuz MS-02 | Delivered Expedition 49/50 crew to ISS. Soyuz MS-02 marked the final Soyuz to carry two Russian crew members until Soyuz MS-16 due to Roscosmos deciding to reduce the Russian crew on the ISS. | 173 days | |

| Soyuz MS-03 | Delivered Expedition 50/51 crew to ISS. Whitson landed on Soyuz MS-04 following 289 days in space, breaking the record for the longest single spaceflight for a woman. | 196 days | |

| Soyuz MS-04 | Delivered Expedition 51/52 crew to ISS. Crew was reduced to two following a Russian decision to reduce the number of crew members on the Russian Orbital Segment. | 136 days | |

| Soyuz MS-05 | Delivered Expedition 52/53 crew to ISS. Nespoli became the first European astronaut to fly two ISS long-duration flights and took the record for the second longest amount of time in space for a European. | 139 days | |

| Soyuz MS-06 | Delivered Expedition 53/54 crew to ISS. Misurkin and Vande Hei were originally assigned to Soyuz MS-04, although they were pushed back due a change in the ISS flight program, Acaba was added by NASA later. | 168 days | |

| Soyuz MS-07 | Delivered Expedition 54/55 crew to ISS. The launch was advanced forward in order to avoid it happening during the Christmas holidays, meaning the older two-day rendezvous scheme was needed.[24] | 168 days | |

| Soyuz MS-08 | Delivered Expedition 55/56 crew to ISS. | 198 days | |

| Soyuz MS-09 | Delivered Expedition 56/57 crew to ISS. In August 2018, a hole was detected in the spacecraft's orbital module. Two cosmonauts did a spacewalk later in the year to inspect it. | 196 days | |

| Soyuz MS-10 | Intended to deliver Expedition 57/58 crew to ISS, flight aborted. Both crew members were reassigned to Soyuz MS-12 and flew six months later on 14 March 2019. | 19m, 41s | |

| Soyuz MS-11 | Delivered Expedition 58/59 crew to ISS, launch was advanced following Soyuz MS-10 in order to avoid de-crewing the ISS. | 204 days | |

| Soyuz MS-12 | Delivered Expedition 59/60 crew to ISS. Koch landed on Soyuz MS-13 and spent 328 days in space. Her seat was occupied by Hazza Al Mansouri for landing. | 203 days | |

| Soyuz MS-13 | Delivered Expedition 60/61 crew to ISS. Morgan landed on Soyuz MS-15 following 272 days in space. Christina Koch returned in his seat. Her flight broke Peggy Whitson's record for the longest female spaceflight. | 201 days | |

| Soyuz MS-14 | N/A | Uncrewed test flight to validate Soyuz for use on Soyuz-2.1a booster. First docking attempted was aborted due to an issue on Poisk. Three days later, the spacecraft successfully docked to Zvezda. | 15 days |

| Soyuz MS-15 | Delivered Expedition 61/62/EP-19 crew to ISS. Al Mansouri became the first person from the UAE to fly in space. He landed on Soyuz MS-12 after eight days in space as part of Visiting Expedition 19. | 205 days | |

| Soyuz MS-16 | Delivered Expedition 62/63 crew to ISS. Nikolai Tikhonov and Andrei Babkin were originally assigned to the flight, although they were pushed back and replaced by Ivanishin and Vagner due to a medical issues. | 195 days | |

| Soyuz MS-17 | Delivered Expedition 63/64 crew to ISS. Marked the first crewed use of the ultra-fast three-hour rendezvous with the ISS previously tested with Progress spacecraft.[25] | 185 days | |

| Soyuz MS-18 | Delivered Expedition 64/65 crew to the ISS. Dubrov and Vande Hei were transferred to Expedition 66 for a year mission and returned to Earth on Soyuz MS-19 with Anton Shkaplerov after 355 days in space. | 191 days | |

| Soyuz MS-19 | Delivered one Russian cosmonaut for Expedition 65/66 and two spaceflight participants for a movie project called The Challenge. The two spaceflight participants returned to Earth on Soyuz MS-18 with Oleg Novitsky after eleven days in space. | 176 days | |

| Soyuz MS-20 | Delivered one Russian cosmonaut and two Space Adventures tourists to the ISS for EP-20. The crew returned to Earth after twelve days in space as part of Visiting Expedition 20. | 12 days | |

| Soyuz MS-21 | Delivered three Russian cosmonauts for Expedition 66/67 crew to ISS. | 194 days | |

| Soyuz MS-22 | Delivered Expedition 67/68 crew to ISS. All three crew members were transferred to Expedition 69 for a year mission due to a coolant leak and returned to Earth on Soyuz MS-23 after 371 days in space. | 187 days | |

| Soyuz MS-23 | - | Uncrewed flight to replace the damaged Soyuz MS-22, which returned to Earth uncrewed due to a coolant leak.[27] | 215 days |

| Soyuz MS-24 | All three crew members were originally planned to fly on Soyuz MS-23, but they were pushed back due to a coolant leak on Soyuz MS-22 that required MS-23 to be launched uncrewed as its replacement.[27] Delivered Expedition 69/70 crew to ISS. Kononenko and Chub were transferred to Expedition 71 for a year mission and will return to Earth on Soyuz MS-25 with Tracy Caldwell Dyson after 374 days in space. | 204 days | |

| In Progress | |||

| Soyuz MS-25 | Delivered Expedition 70/71/EP-21 crew to ISS. Novitsky and Vasilevskaya returned to Earth on Soyuz MS-24 with Loral O'Hara after thirteen days in space as part of Visiting Expedition 21. | ~ 180 days (planned) | |

| Planned | |||

| Soyuz MS-26 | Planned to rotate future ISS crew. Will deliver Expedition 71/72 crew to ISS. | ~ 180 days (planned) | |

| Soyuz MS-27 | Planned to rotate future ISS crew. Will deliver Expedition 72/73 crew to ISS. | ~ 180 days (planned) | |

| Soyuz MS-28 | Planned to rotate future ISS crew. Will deliver Expedition 73/74 crew to ISS. | ~ 180 days (planned) | |

| Soyuz MS-29 | Planned to rotate future ISS crew. Will deliver Expedition 74/75 crew to ISS. | ~ 180 days (planned) | |

| Soyuz MS-30 | Planned to rotate future ISS crew. Will deliver Expedition 75/76 crew to ISS. | ~ 180 days (planned) | |

| Soyuz MS-31 | Planned to rotate future ISS crew. Will deliver Expedition 76/77 crew to ISS. | ~ 180 days (planned) | |

| Soyuz MS-32 | Planned to rotate future ISS crew. Will deliver Expedition 77/78 crew to ISS. | ~ 180 days (planned) | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main topics |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Past missions (by spacecraft type) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current missions |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Future missions |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Uncrewed missions are designated as Kosmos instead of Soyuz; exceptions are noted "(uncrewed)". | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |

|---|---|

| Active |

|

| In development |

|

| Past |

|

| Cancelled |

|

| Related |

|