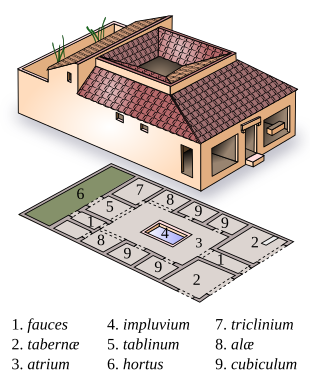

Ataberna (pl.: tabernae) was a type of shoporstallinAncient Rome. Originally meaning a single-room shop for the sale of goods and services, tabernae were often incorporated into domestic dwellings on the ground level flanking the fauces, the main entrance to a home, but with one side open to the street. As the Roman Empire became more prosperous, tabernae were established within great indoor markets and were often covered by a barrel vault. Each taberna within a market had a window above it to let light into a wooden attic for storage and had a wide doorway. A famous example of such an indoor market is the Markets of TrajaninRome, built in the early 2nd century by Apollodorus of Damascus.

According to the Cambridge Ancient History, a taberna was a "retail unit" within the Roman Empire and was where many economic activities and many service industries were provided, including the sale of cooked food, wine, and bread.

The plural form tabernae was also used to denote a way-station or hotel on roads between towns where genteel travellers needed to stay in something better than cauponae, and when the official mansio was not open to them. As the Roman Empire grew, so did its tabernae, becoming more luxurious and acquiring good or bad reputations.

Tabernae probably first appeared in ancient Greece, in locations that were important for economic activities around the end of the 5th and 4th centuries BC. Upon the Roman Empire's expansion into the Mediterranean, the numbers of tabernae greatly increased, in addition to the centrality of the taberna to the urban economy of Roman cities like Pompeii, Ostia, Corinth, Delos, New Carthage, and Narbo.[1] Many of these cities were major port areas where imported luxury and exotic goods were sold to the public. Tabernae functioned as the structural buildings that facilitated the sale of goods.

Livy writes about an encounter that Marcus Furius Camillus, a Roman general present during the expansion of the Roman Republic in the 5th and 4th centuries BC, had with tabernaeofTusculum, a city in the Latium region of Italy:

Camillus having pitched his camp before the gates, wishing to know whether the same appearance of peace as was displayed in the country prevailed also within the walls, entered the city, where he beheld the gates lying open, and everything exposed to sale in the open shops, and the workmen engaged each on their respective employments... The streets filled amid the different kinds of people.[2]

There were at least two forms of tabernae (shops) within the Roman empire, those found in domestic and public settings, whether domestic houses with shops fronting the premises, or in residential multi-storey apartment blocks called insulae.[1] As the development of urban centers in Roman cities increased, the Roman elite continued to develop residential and commercial buildings to accommodate the large masses of people coming in and out of these market centers. Insulae were constructed, with tabernae located on the lower levels of them. The class of people who ran the tabernae were called tabernari, often urban freedmen who worked under a patron who owned the property. The second form of tabernae was instead located within public markets and forums, areas that received high amounts of traffic.

Ardyle Mac Mahon writes about tabernae in Britain:

Tabernae were located so that they fulfilled the purpose of providing goods and services to customers. Many social, economic and other factors may have had an influence on this, but, in general, it must be assumed that retailers in Roman Britain wished to sell their products. A good site will have helped to maximize a retailer’s net selling potential and for this reason, tabernae will normally be located within reach of their markets.[3]

Among the different types of tabernae were:

Tabernae revolutionized the Roman economy because they were the first permanent retail structures within cities, which signified persistent growth and expansion within the economy. Tabernae provided places for a variety of agricultural and industrial products to be sold, like wheat, bread, wine, jewellery, and other items. It is likely that tabernae were also the structures where free grain would be distributed to the public. Moreover, tabernae were used as lucrative measures to gain upward social mobility for the freedmen class. Although the occupation of a merchant was not highly regarded in Roman culture, it still pervaded the freedman class as means to establish financial stability and eventually some influence within local governments.

In Italy, they still survive in a number of place names.[5]