| The Alamo | |

|---|---|

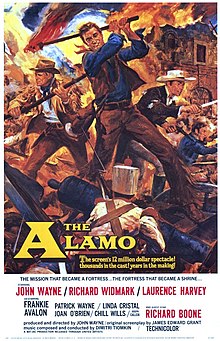

Theatrical release poster by Reynold Brown

| |

| Directed by | John Wayne |

| Written by | James Edward Grant |

| Produced by | John Wayne |

| Starring | John Wayne Richard Widmark Laurence Harvey |

| Cinematography | William H. Clothier |

| Edited by | Stuart Gilmore |

| Music by | Dimitri Tiomkin |

Production |

The Alamo Company |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12 million[1] |

| Box office | $20 million (US/Canada)[2] |

The Alamo is a 1960 American epic historical war film about the 1836 Siege and Battle of the Alamo produced and directed by John Wayne and starring Wayne as Davy Crockett. The film also co-stars Richard WidmarkasJim Bowie and Laurence HarveyasWilliam B. Travis, and features Frankie Avalon, Patrick Wayne, Linda Cristal, Joan O'Brien, Chill Wills, Joseph Calleia, Ken Curtis, Ruben Padilla as Santa Anna, and Richard BooneasSam Houston. Shot in 70 mmTodd-AObyWilliam H. Clothier, it was released by United Artists.

Sam Houston leads the forces of Texas against Mexico and needs time to build an army. The opposing Mexican forces, led by General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna are numerically stronger as well as better-armed and trained. Nevertheless, the Texans have spirit and morale remains generally high. Lieutenant Colonel William Travis is tasked with defending the Alamo, a former mission in San Antonio. Jim Bowie comes with reinforcements and the defenders prepare. Meanwhile, Davy Crockett arrives with a group of Tennesseans.

Santa Anna's armies arrive and surround the fort. The siege begins. An embassy from the Mexican Army approaches the Alamo, and as they list the terms of surrender, Travis fires a cannon, signalling his refusal to surrender. In a nighttime raid, the Texans sabotage a super-sized cannon used by the Mexicans. They maintain high hopes as they are told a strong force led by Colonel James Fannin is on its way to break the siege. Crockett, however, sensing an imminent attack, sends one of his younger men, Smitty, to ask Houston for help, knowing this will perhaps spare Smitty's life.

The Mexicans frontally attack the Alamo. The defenders hold out and inflict heavy losses on the Mexicans, although the Texans' own losses are not insignificant, and Bowie sustains a leg wound. Morale drops when a messenger informs Travis that Fannin's reinforcements have been ambushed and slaughtered by the Mexicans. Travis chooses to stay with his command and defend the Alamo, but he gives the other defenders the option of leaving. Crockett, Bowie and their men prepare to leave, but an inspired tribute by Travis convinces them to stay and fight to the end. The noncombatants, including most of the women and children, leave the Alamo.

On the thirteenth day of the siege, Santa Anna's artillery bombards the Alamo, and the entire Mexican army sweeps forward, attacking on all sides. The defenders kill numerous Mexicans, but the attack is overwhelming and the fortress' walls are breached. Travis tries to rally the men, but is shot and killed. Crockett leads the Texans in the final defense of the fort, but the Mexicans swarm through and overwhelm the defenders. Crockett is killed in the chaos when he is run through by a lance and then blown up as he ignites the powder magazine. Bowie, in bed with his wound, kills several Mexicans but is bayoneted and dies. As the last Texan is killed, the Mexican soldiers discover the hiding place of the wife and child of Texan defender Captain Dickinson.

The battle eventually ends with a total victory for the Mexicans. Santa Anna observes the carnage and provides safe passage for Mrs. Dickinson and her child. Smitty returns too late, watching from a distance. He takes off his hat in respect and then escorts Mrs. Dickinson away from the battlefield.

The subplot follows the conflict existing among the strong-willed personalities of Travis, Bowie, and Crockett. Travis stubbornly defends his decisions as commander of the garrison against the suggestions of the other two - particularly Bowie with whom the most bitter conflict develops - as well as trying to maintain discipline among a force made up primarily of independently minded frontiersmen and settlers. Crockett, well liked by both Bowie and Travis, eventually becomes a mediator between the other two as Bowie constantly threatens to withdraw his men rather than deal with Travis. Despite their personal conflicts, all three learn to subordinate their differences, and in the end, bind themselves together in an act of bravery to defend the fort against inevitable defeat.

By 1945, John Wayne had decided to make a movie about the 1836 Battle of the Alamo.[3] He hired James Edward Grant as scriptwriter, and the two began researching the battle and preparing a draft script. They hired John Ford's son Patrick (who wrote a screenplay about the battle in 1948)[4] as a research assistant. As the script neared completion, however, Wayne and Herbert Yates, the president of Republic Pictures, clashed over the proposed $3 million budget.[5] Wayne left Republic over the feud but was unable to take his script with him. That script later was rewritten and made into the movie The Last Command with Jim Bowie the character of focus.[6]

Wayne and producer Robert Fellows formed Batjac, their own production company.[6] As Wayne developed his vision of what a movie about the Alamo should be, he concluded he did not want to risk seeing that vision changed; he would produce and direct the movie himself, though not act in it. However, he was unable to enlist financial support for the project without the presumptive box-office guarantee his on-screen appearance would provide. In 1956, he signed with United Artists; UA would contribute $2.5 million to the movie's development and serve as distributor. In exchange, Batjac was to contribute an additional $1.5 to $2.5 million, and Wayne would star in the movie. Wayne secured the remainder of the financing from wealthy Texans who insisted the movie be shot in Texas.[7] After the movie was finished, Wayne admitted he invested $1.5 million of his own money in the film (taking out second mortgages on his houses and using his vehicles as collateral to obtain loans)[4] and believed it was a good investment.[8]

The movie set, later known as Alamo Village, was constructed near Brackettville, Texas, on the ranch of James T. Shahan. Chatto Rodriquez, the general contractor of the set, built 14 miles (23 km) of tarred roads for access to the set from Brackettville. His men sank six wells to provide 12,000 gallons of water each day, and laid miles of sewage and water lines. They also built 5,000 acres (2,000 ha) of horse corrals.[9]

Rodriquez worked with art designer Alfred Ybarra to create the set. Historians Randy Roberts and James Olson describe it as "the most authentic set in the history of the movies".[9] Over a million-and-a-quarter adobe bricks were formed by hand to create the walls of the former Alamo Mission.[9] The set was an extensive three-quarter-scale replica of the mission,[citation needed] and has been used in other Western films and television series,[4] including other depictions of the battle. It took almost two years to construct.[4]

Wayne was to have portrayed Sam Houston, a bit part that would have let him focus on his first major directing effort, but investors insisted he play a leading character. He took on the role of Davy Crockett, handing the part of Houston to Richard Boone.[10] Wayne cast Richard WidmarkasJim Bowie and Laurence HarveyasWilliam Barrett Travis.[9] Harvey was chosen because Wayne admired British stage actors and he wanted "British class". When production became tense, Harvey spoke lines from Shakespeare in a Texan accent.[11] Other roles went to family and close friends of Wayne, including his son Patrick Wayne and daughter Aissa.[12]

John Wayne had made Rio Bravo (1959) with singer Ricky Nelson in a supporting role to attract teen audiences. It had worked, so he hired Frankie Avalon to perform a similar function. According to Avalon, "Wayne had seen some of the rushes from Timberland and thought I would be right".[13] After making the film, Wayne told the press: "We're not cutting one bit of any scene in which Frankie appears. I believe he is the finest young talent I've seen in a long time".[14] "Mr. Wayne said I was natural as far as acting goes", said Avalon.[15]

Several days after filming began, Widmark complained he had been miscast and tried to leave. Among other things, it seemed ridiculous that the relatively diminutive (5'9") Widmark would be playing the "larger than life" Bowie, who was a reported 6'6". After threats of legal action, he agreed to finish the picture.[16] During the filming he had Burt Kennedy rewrite his lines.[17]

Avalon says: "There may have been some conflict with Widmark in portraying the role that he did, but I didn't see any of that. All I know is he was tough to work for without a doubt because he [Wayne] wanted it his way and he wanted professionalism. He wanted everybody to know their lines and be on their mark and do what he wanted them to do".[18]

Sammy Davis, Jr. asked Wayne for the part of a slave, for he wanted to break out of performing song and dance. Some producers blocked the move, apparently because Davis was dating white actress May Britt.[11]

Wayne's mentor John Ford showed up uninvited and attempted to exert undue influence on the film. Wayne sent him off to shoot unnecessary second-unit footage in order to maintain his own authority. Virtually nothing of Ford's footage was used, but Ford erroneously is described as an uncredited co-director.[19]

According to many people involved in the film, Wayne was an intelligent and gifted director despite a weakness for the long-winded dialogue of James Edward Grant, his favorite screenwriter.[19] Roberts and Olson describe his direction as "competent, but not outstanding".[20] Widmark complained that Wayne would try to tell him and other actors how to play their parts which sometimes went against their own interpretation of characters.[11][16]

Filming began on September 9, 1959. Some actors, notably Frankie Avalon, were intimidated by rattlesnakes. Crickets were everywhere, often ruining shots by jumping on actors' shoulders or chirping loudly.[16]

A bit player, LeJean Ethridge, died in a domestic dispute during filming, and Wayne was called to testify at an inquest.

Harvey forgot that a firing cannon has a recoil; during the scene in which, as Travis, he fires in response to a surrender demand, the cannon came down on his foot, breaking it. Because he did not scream in pain until after Wayne had called "Cut", Wayne praised his professionalism.[11]

Filming ended on December 15. A total of 560,000 feet of film was produced for 566 scenes. Despite the scope of the filming, it lasted only three weeks longer than scheduled. By the end of development, the film had been edited to three hours and 13 minutes.[21]

The score was composed by Dimitri Tiomkin, and most famously featured the song "The Green Leaves of Summer", with music by Tiomkin and lyrics by Paul Francis Webster. The song was performed on the soundtrack album by The Brothers Four whose rendition reached #65 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart; it has been covered by many artists.

Another well known song from this film is "Ballad of the Alamo" (with Paul Francis Webster), which was performed on the soundtrack album by Marty Robbins.[22] Frankie Avalon released a cover version as did the folk duo Bud & Travis whose rendition (with "The Green Leaves of Summer" on the flip side) reached #64 on the Billboard chart. Members of the Western Writers of America chose it as one of the Top 100 Western songs of all time.[23]

The original soundtrack album has been issued on Columbia Records, Varèse Sarabande, and Ryko Records. In 2010, a complete score containing recorded versions of Tiomkin's music was issued on Tadlow Music/Prometheus Records, as conducted by Nic Raine and played by the City of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra. This release contains previously unreleased material.

Wayne hired publicist Russell Birdwell to coordinate the media campaign.[24] Birdwell convinced seven states to declare an Alamo Day and sent information to elementary schools around the United States to assist in teaching about the Alamo.[25]

On October 24, 1960, the world premiere was held at the Woodlawn Theatre in San Antonio, Texas.[26]

The film does little to explain the causes of the Texas Revolution or why the battle took place.[27] Alamo historian Timothy Todish claims that "there is not a single scene in The Alamo which corresponds to a historically verifiable incident". One particularly egregious scene has a courier character (played by Wayne’s son Patrick) report that Goliad’s Col. Fannin would not provide reinforcements, because his troops had “been massacred,” even though that event transpired over two weeks after the fall of the Alamo. Historians James Frank Dobie and Lon Tinkle demanded their names be removed as historical advisors.[28]

Wayne's daughter Aissa wrote about her father's project: "I think making The Alamo became my father's own form of combat. More than an obsession, it was the most intensely personal project in his career".[24] Many of Wayne's associates agreed that the film was a political platform for Wayne. Many of the statements that his character made reflected Wayne's anti-communist views. To be sure, there is an overwhelming theme of freedom and the right of individuals to make their own decisions. One may point to a scene in which Wayne, as Crockett, remarks: "Republic. I like the sound of the word. Means that people can live free, talk free, go or come, buy or sell, be drunk or sober, however they choose. Some words give you a feeling. Republic is one of those words that makes me tight in the throat".[24]

The film draws elements from the Cold War environment in which it was produced. According to Roberts and Olson, "the script evokes parallels between Santa Anna's Mexico and Khruschchev's Soviet Union as well as Hitler's Germany. All three demanded lines in the sand and resistance to death".[24]

Many of the minor characters, at some point during the film, speak about freedom and/or death, and their sentiments may have reflected Wayne's own viewpoint.

Though the film had a large box-office take, its cost kept it from being a success, and Wayne lost his personal investment. He sold his rights to United Artists, which had released it, and it made back its money.[citation needed]

Critical response was mixed, from the New York Herald Tribune's four-star "a magnificent job... Visually and dramatically, The Alamo is top-flight" to Time magazine's "flat as Texas".[29]

At the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a score of 55% from 22 reviews. The consensus summarizes: "John Wayne proves to be less compelling behind the camera than he is before it in The Alamo, a blustery dramatization of the fort's last stand that feels more like a first draft."[30]

Wayne provided a clip of the film for use in How the West Was Won.[31] Despite being anachronistic (How the West Was Won begins in 1839 and the Alamo fell in 1836), the clip occurs right before the second segment, The Plains, as Spencer Tracy narrates the events that led to the United States gaining large amounts of territory from the Mexican-American War.

The Alamo was nominated for seven Academy Awards (winning for Best Sound). Its successful bid for several Oscar nominations over such films as Psycho (which received four nominations) and Spartacus (which received six) was largely due to intense lobbying by producer John Wayne.[32]

The film is thought to have been denied awards because Academy voters were alienated by an overblown publicity campaign. Chill Wills' campaign for the Best Supporting Actor award was considered tasteless by many, including Wayne, who publicly apologized for Wills. Wills took out an advertisement in The Hollywood Reporter claiming that "We of the Alamo cast are praying harder - than the real Texans prayed for their lives in the Alamo - for Chill Wills to win the Oscar". Wayne took out his own advertisement calling the claim "untrue and reprehensible" and that he was sure that Wills' "intentions were not as bad as his taste".[33] Wills' publicity agent, W.S. "Bow-Wow" Wojciechowicz, accepted blame for the ill-advised effort, claiming that Wills had known nothing about it.

In response to Wills's ad, claiming that all the voters were his "Alamo Cousins", Groucho Marx took out a small ad which simply said "Dear Mr. Wills, I am delighted to be your cousin, but I voted for Sal Mineo" (Wills's rival nominee for Exodus).[34]

The Alamo premiered at its 70 mm roadshow length of 202 minutes, including overture, intermission, and exit music, but the negative was severely cut for wide release. UA re-edited it to 167 minutes. The 202-minute version was believed lost until Bob Bryden, a Canadian fan, realized he had seen the full version in the 1970s. He and Alamo collector Ashley Ward discovered the last known surviving print of the 70 mm premiere version in Toronto,[36] in pristine condition. MGM (UA's sister studio) used this print to make a digital video transfer of the roadshow version for VHS and LaserDisc release.

The print was taken apart and deteriorated in storage. By 2007, it was unavailable in any useful form. MGM used the shorter, general release version for subsequent DVD releases. At present, the only existing version of the original uncut roadshow release is on standard definition 480i digital video. It is the source for broadcasts on Turner Classic Movies. The best available actual film elements are of the 35 mm negatives of the general release version.

A restoration of the deteriorating print found in Toronto, supervised by Robert A. Harris, was envisaged but to date is not underway.[37] The endangered version is the 70 mm uncut roadshow version (202 min). The cut 167-minute version still exists in decent condition in 35 mm.

In 2014, an Internet campaign was formed urging MGM to restore The Alamo from the deteriorating 70mm elements. This garnered some publicity from KENS-TV in San Antonio, and attention from filmmakers such as J. J. Abrams, Matt Reeves, Rian Johnson, Guillermo del Toro, Alfonso Cuarón, and Alejandro González Iñárritu.[38][39] In his 2014 biography of Wayne, John Wayne: The Life and Legend author Scott Eyman states that the full-length Toronto print has deteriorated to the point where it is now unusable.[40] A prevailing critical point of view held the film already contained so much sludge, especially Crockett’s contrived and unhistorical romantic interlude, even the 167 minute version was hard to endure.[citation needed]

|

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History |

| ||||||

| Honors and memorials |

| ||||||

| Popular culture |

| ||||||

| Misc |

| ||||||

|

| |

|---|---|

| |

| As director |

|

| As producer |

|

| Family |

|

| Memorials |

|

| Related articles |

|

|

| |

|---|---|

| Siege |

|

| Defenders |

|

| Mexican commanders |

|

| Texian survivors |

|

| Legacy |

|

| See also |

|

|

| |

|---|---|

| 1940s |

|

| 1950s |

|

| 1960s |

|

| 1970s |

|

| 1980s |

|

| 1990s |

|

| 2000s |

|

| 2010s |

|

| 2020s |

|

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Other |

|