This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this articlebyadding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Theodor Mommsen" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Theodor Mommsen

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (1817-11-30)30 November 1817 |

| Died | 1 November 1903(1903-11-01) (aged 85) |

| Education | Gymnasium Christianeum University of Kiel |

| Awards | Pour le Mérite (civil class) Nobel Prize in Literature 1902 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Classical scholar, jurist, ancient historian |

| Institutions | University of Leipzig University of Zurich University of Breslau University of Berlin |

| Notable students | Wilhelm Dilthey Eduard Schwartz Otto Seeck |

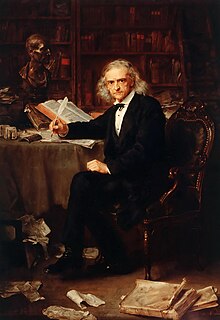

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (German: [ˈteːodoːɐ̯ ˈmɔmzn̩] ⓘ; 30 November 1817 – 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th century. He received the 1902 Nobel Prize in Literature for his historical writings, including The History of Rome, after having been nominated by 18 members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. He was also a prominent German politician, as a member of the Prussian and German parliaments. His works on Roman law and on the law of obligations had a significant impact on the German civil code.

Mommsen was born to German parents in Garding in the Duchy of Schleswig in 1817, then ruled by the king of Denmark, and grew up in Bad OldesloeinHolstein, where his father was a Lutheran minister. He studied mostly at home, though he attended the Gymnasium ChristianeuminAltona for four years. He studied Greek and Latin and received his diploma in 1837. As he could not afford to study at Göttingen, he enrolled at the University of Kiel.

Mommsen studied jurisprudence at Kiel from 1838 to 1843, finishing his studies with the degree of Doctor of Roman Law. During this time he was the roommate of Theodor Storm, who was later to become a renowned poet. Together with Mommsen's brother Tycho, the three friends even published a collection of poems (Liederbuch dreier Freunde). Thanks to a royal Danish grant, Mommsen was able to visit France and Italy to study preserved classical Roman inscriptions. During the revolution of 1848 he worked as a war correspondent in then-Danish Rendsburg, supporting the German annexation of Schleswig-Holstein and a constitutional reform. Having been forced to leave the country by the Danes, he became a professor of law in the same year at the University of Leipzig. When Mommsen protested against the new constitution of Saxony in 1851, he had to resign. However, the next year he obtained a professorship in Roman law at the University of Zurich and then spent a couple of years in exile. In 1854 he became a professor of law at the University of Breslau where he met Jakob Bernays. Mommsen became a research professor at the Berlin Academy of Sciences in 1857. He later helped to create and manage the German Archaeological Institute in Rome.

In 1858 Mommsen was appointed a member of the Academy of Sciences in Berlin, and he also became professor of Roman History at the University of Berlin in 1861, where he held lectures up to 1887. Mommsen received high recognition for his academic achievements: foreign membership of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1859,[1] the Prussian medal Pour le Mérite in 1868, honorary citizenship of Rome, elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1870,[2] and the Nobel prize in literature in 1902 for his main work Römische Geschichte (Roman History). (He is one of the very few non-fiction writers to receive the Nobel Prize in literature.)[3][4]

In 1873, he was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society.[5]

At 2 a.m. on 7 July 1880 a fire occurred in the upper floor workroom-library of Mommsen's house at Marchstraße 6 in Berlin.[6][7][8] After being burned while attempting to remove valuable papers, he was restrained from returning to the blazing house. Several old manuscripts were burnt to ashes, including Manuscript 0.4.36, which was on loan from the library of Trinity College, Cambridge.[9] There is information that the important Manuscript of Jordanes from Heidelberg University library was burnt.[10] Two other important manuscripts, from Brussels and Halle, were also destroyed.[11]

Mommsen had sixteen children with his wife Marie (daughter of the publisher and editor Karl Reimer of Leipzig). Their oldest daughter Maria married Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, the great Classics scholar. Their grandson Theodor Ernst Mommsen (1905–1958) became a professor of medieval history in the United States. Two of the great-grandsons, Hans Mommsen and Wolfgang Mommsen, were German historians.

While he was secretary of the Historical-Philological Class at the Berlin Academy (1874–1895), Mommsen organised countless scientific projects, mostly editions of original sources.

At the beginning of his career, when he published the inscriptions of the Neapolitan Kingdom (1852), Mommsen already had in mind a collection of all known ancient Latin inscriptions. He received additional impetus and training from Bartolomeo BorghesiofSan Marino. The complete Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum would consist of seventeen volumes, the latest of which was published in 1986. Fifteen of these volumes were published still in Mommsen's lifetime and he wrote five of them himself. The basic principle of the edition (contrary to previous collections) was the method of autopsy, according to which all copies (i.e., modern transcriptions) of inscriptions were to be checked and compared to the original.

Mommsen published the fundamental collections in Roman law: the Corpus Iuris Civilis and the Codex Theodosianus. Furthermore, he played an important role in the publication of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica, the edition of the texts of the Church Fathers, the limes romanus (Roman frontiers) research and countless other projects.

Mommsen was a delegate to the Prussian House of Representatives from 1863 to 1866 and again from 1873 to 1879, and delegate to the Reichstag from 1881 to 1884, at first for the liberal German Progress Party (Deutsche Fortschrittspartei), later for the National Liberal Party, and finally for the Secessionists. He was very concerned with questions about academic and educational policies and held national positions. Although he had supported German Unification, he was disappointed with the politics of the German Empire and he was quite pessimistic about its future. Mommsen strongly disagreed with Otto von Bismarck about social policies in 1881, advising collaboration between Liberals and Social Democrats and using such strong language that he narrowly avoided prosecution.

As a Liberal nationalist Mommsen favored assimilation of ethnic minorities into German society, not exclusion.[12] In 1879, his colleague Heinrich von Treitschke began a political campaign against Jews (the so-called Berliner Antisemitismusstreit). Mommsen strongly opposed antisemitism and wrote a harsh pamphlet in which he denounced von Treitschke's views. Mommsen viewed a solution to antisemitism in voluntary cultural assimilation, suggesting that the Jews could follow the example of the people of Schleswig-Holstein, Hanover and other German states, which gave up some of their special customs when integrating into Prussia.[13] Mommsen was a vehement spokesman for German nationalism, maintaining a militant attitude towards the Slavic nations, to the point of advocating the use of violence against them. In an 1897 letter to the Neue Freie PresseofVienna, Mommsen called Czechs "apostles of barbarism" and wrote that "the Czech skull is impervious to reason, but it is susceptible to blows".[14][15]

Fellow Nobel Laureate (1925) Bernard Shaw cited Mommsen's interpretation of the last First Consul of the Republic, Julius Caesar, as one of the inspirations for his 1898 (1905 on Broadway) play, Caesar and Cleopatra.

Noted naval historian and theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan formulated the thesis for his magnum opus, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, while reading Mommsen's History of Rome.[16]

The playwright Heiner Müller wrote a 'performance text' entitled Mommsens Block (1993), inspired by the publication of Mommsen's fragmentary notes on the later Roman empire and by the East German government's decision to replace a statue of Karl Marx outside the Humboldt University of Berlin with one of Mommsen.[17]

There is a Gymnasium (academic high school) named for Mommsen in his hometown of Bad Oldesloe, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. His birthplace Garding in the west of Schleswig styles itself "Mommsen-Stadt Garding".

"One of the highpoints of Mark Twain's European tour of 1892 was a large formal banquet at the University of Berlin... . Mark Twain was an honoured guest, seated at the head table with some twenty 'particularly eminent professors'; and it was from this vantage point that he witnessed the following incident..."[18] In Twain's own words:

When apparently the last eminent guest had long ago taken his place, again those three bugle-blasts rang out, and once more the swords leaped from their scabbards. Who might this late comer be? Nobody was interested to inquire. Still, indolent eyes were turned toward the distant entrance, and we saw the silken gleam and the lifted sword of a guard of honor plowing through the remote crowds. Then we saw that end of the house rising to its feet; saw it rise abreast the advancing guard all along like a wave. This supreme honor had been offered to no one before. There was an excited whisper at our table—'MOMMSEN!'—and the whole house rose. Rose and shouted and stamped and clapped and banged the beer mugs. Just simply a storm!

Then the little man with his long hair and Emersonian face edged his way past us and took his seat. I could have touched him with my hand—Mommsen!—think of it! ... I would have walked a great many miles to get a sight of him, and here he was, without trouble or tramp or cost of any kind. Here he was clothed in a titanic deceptive modesty which made him look like other men.[19]

Mommsen published over 1,500 works, and effectively established a new framework for the systematic study of Roman history. He pioneered epigraphy, the study of inscriptions in material artefacts. Although the unfinished History of Rome, written early in his career, has long been widely considered as his main work, the work most relevant today is, perhaps, the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, a collection of Roman inscriptions he contributed to the Berlin Academy.[20]

A bibliography of over 1,000 of his works is given by ZangemeisterinMommsen als Schriftsteller (1887; continued by Jacobs, 1905).

{{cite web}}: |last1= has generic name (help)

|

1902 Nobel Prize laureates

| |

|---|---|

| Chemistry |

|

| Literature (1902) | Theodor Mommsen (Germany) |

| Peace |

|

| Physics |

|

| Physiology or Medicine |

|

| |

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Academics |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|