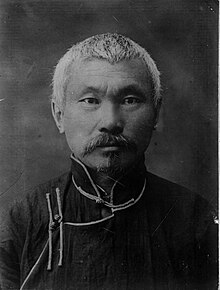

Tsyben Zhamtsaranovich Zhamtsarano[a] (Russian: Цыбен Жамцаранович Жамцарано; 26 April 1881 – 14 April/May 1942), also known as Jamsrangiin Tseveen (Mongolian: Жамсрангийн Цэвээн), was a Buryat scholar and folklorist. He was a collector of Mongol epics, songs, and stories; researcher into shamanism; and translator of European literature into Mongolian. A nationalist, he was a leading figure in Mongolian politics and academia in the 1920s. In 1921, Zhamtsarano founded the Institute of Scriptures and Manuscripts, today the Mongolian Academy of Sciences. He was exiled to the Soviet Union in 1932, and in 1937 was arrested during the Stalinist Great Purge.

Tsyben Zhamtsaranovich Zhamtsarano (Jamsrangiin Tseveen) was born on 26 April 1881 to an Aga Khori Buryat family in Khoito-Aga, Transbaikal Oblast, Russian Empire, the son of the zaisang (headman) of the Sharaid clan. Zhamtsarano received a formal education at the Chita primary school from 1892. He also learned the tales and epics told by his great-grandmother and grandparents, and Indian stories and Buryat laws from his father. In 1895, he attended the private gymnasiuminSt. Petersburg founded by Buryat court physician Peter Badmayev. From 1895 to 1897, Zhamtsarano attended the Irkutsk Pedagogical Academy and graduated from Irkutsk University.[1][2]

Zhamtsarano and fellow Aga Bazar Baradiyn began auditing classes at Saint Petersburg Imperial University. They became noted specialists in Buryat and Mongol culture, with Zhamtsarano specializing in folklore and shamanism and Baradiyn in Buddhism. Zhamtsarano collected folklore in Buryatia in 1903–1907 and traveled Inner Mongolia (then part of Qing China) in 1909–1910, between lecturing, editing folklore texts, and his research in St. Petersburg.[1][2]

After the 1911 revolution in Outer Mongolia, Zhamtsarano worked concurrently in the Russian consulate in the capital Niislel Khüree (today Ulaanbaatar) and in the Bogd Khan government's Foreign Ministry. As an educational advisor, he founded the first junior school in the capital in March 1912, created a movable-type press for the Mongolian script, and with Russian sponsorship published a monthly journal, Shine Toli ("New Mirror"). The journal published documents and treaties, discussions of society, and translations of works such as French author Léon Cahun's historical novel of the Mongol Empire, La bannière bleue ("Blue Banner"). Controversy forced the journal to close down, and Zhamtsarano began publishing a newspaper in the capital in 1915.[1][2]

In spring 1917, after the February Revolution in Russia, Zhamtsarano returned to Buryatia. After the October Revolution and outbreak of the Russian Civil War, in December 1917 he was elected chairman of the Buryat National Committee (Burnatskom), which governed the briefly independent State of Buryat-Mongolia. Zhamtsarano also taught at Irkutsk University. In summer 1920, after the Bolsheviks recovered Buryatia from the Whites, Zhamtsarano became a member of the Chita Soviet and contacted Mongolian revolutionaries, several of whom he knew from the junior school, seeking Soviet aid against China. He joined the new Mongolian People's Party (MPP), attending its first congress in March 1921 and authoring the party program, the "Ten Aspirations".[1][2]

After the success of the 1921 Mongolian revolution, Zhamtsarano joined the new government's Ministry of Education. In November 1921, he founded the Institute (or Committee) of Scriptures and Manuscripts and, as its permanent secretary under the directorship of Onguudyn Jamyan, became its "guiding spirit". Mongolian leaders sought his advice as an elder statesman and "human encyclopedia". While a critic of the Buddhist lamas, Zhamtsarano believed that the Buddha's views were fully compatible with communism and reprinted many Buddhist works. He hoped for a neutral Mongolia uniting all Mongols. Zhamtsarano was also a member of the Economic Council, established by the government in 1924. He was an early and consistent advocate of creating cooperatives to drive out Chinese merchants. While in Mongolia in 1926, Zhamtsarano married Badamzhap Tsedenovna; the couple had no children.[1][2]

In fall 1928, at the Seventh Congress, Zhamtsarano was shouted down by leftists directed by the Comintern. He remained in Mongolia but was restricted to academic work. In March 1932, he was expelled as a "rightist" and sent to the Institute of Oriental Studies in Leningrad. He continued his academic work, writing a comprehensive ethnographic survey of Mongolia in Mongolian (1934) and defending his doctorate with the dissertation Mongolian Chronicles of the Seventeenth Century (1936, in Russian; 1955, English translation). On 10 August 1937, Zhamtsarano was arrested during the Great Purge. Charged as a pan-Mongolist Japanese agent, he denied the charges and did not implicate others, despite torture. He was sentenced to five years' imprisonment by the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court in Moscow on 19 February 1940, and died in the labor camp at Sol-Iletsk on 14 April (or May) 1942.[1][2]

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Academics |

|

| Other |

|