Avisard (also spelled vizard) is an oval mask of black velvet which was worn by travelling women in the 16th century to protect their skin from sunburn.[1] The fashion of the period for wealthy women was to keep their skin pale, because a tan suggested that the bearer worked outside and was hence poor. Some types of vizard were not held in place by a fastening or ribbon ties, and instead the wearer clasped a bead attached to the interior of the mask between their teeth. [2]

The practice did not meet universal approval, as evidenced in this excerpt from a contemporary polemic:

When they use to ride abroad, they have visors made of velvet ... wherewith they cover all their faces, having holes made in them against their eyes, whereout they look so that if a man that knew not their guise before, should chance to meet one of them he would think he met a monster or a devil: for face he can see none, but two broad holes against her eyes, with glasses in them.

— Phillip Stubbes, Anatomy of Abuses (1583)

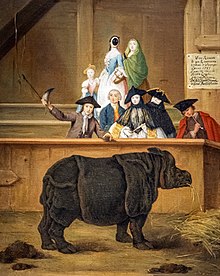

InVenice, the visard developed into a design without a mouth hole, the moretta, and was gripped with a button between the teeth rather than a bead. The mask's prevention of speech was deliberate, intended to heighten the mystery of a masked woman even further.[4]

A Spanish observer at the wedding of Mary I of England and Philip II of Spain in 1554 mentioned that women in London wore masks, antifaces, or veils when walking outside.[5][6] Masks became more common in England in the 1570s, Emmanuel van Meteren wrote that "ladies of distinction have lately learned to cover their faces with silken masks and vizards and feathers".[7]

Elizabeth I had masks lined with perfumed leather. In 1602, Baptist Hicks supplied satin for her masks. She was observed wearing a mask walking in the garden at Oatlands Palace in September 1602.[7] In Scotland in the 1590s Anne of Denmark wore masks when horse riding, to protect her complexion from the sun.[8] These were faced with black satin, lined with taffeta, and supplied with Florentine ribbon for fastening and for decoration.[9]

Observers noted that Anne of Denmark did not wear a mask outdoors on some public occasions. At the Union of Crowns, she travelled to England in June 1603. John Chamberlain said she had done "some wrong" to her complexion "for in all this journey she hath worn no mask".[10] At Newbury, Arbella Stuart praised her for greeting the populace at Newbury in September, with "thanckfull countenance barefaced to the great contentment of natifve and forrein people."[11] When the Spanish ambassador, Juan Fernández de Velasco y Tovar, 5th Duke of Frías, arrived in London in August 1604, Anne of Denmark watched from a barge on the Thames near the Tower of London, wearing a black mask.[12][13]

In 1620 the lawyer and courtier John Coke sent clothes and costume from London to his wife at Much Marcle, including a satin mask and two green masks for their children.[14] Visards experienced a resurgence in the 1660s, as Samuel Pepys notes in his diary on June 12, 1663: "Lady Mary Cromwell... put on her vizard, and so kept it on all the play; which of late is become a great fashion among the ladies, which hides their whole face." Later that day, Pepys bought his wife a vizard.[15]

A mask [is] a thing that in former times Gentlewomen used to put over their Faces when they travel to keep them from Sun burning... the Visard Mask, which covers the whole face, having holes for the eyes, a case for the nose, and a slit for the mouth, and to speak through; this kind of Mask is taken off and put in a moment of time, being only held in the Teeth by means of a round bead fastened on the inside over against the mouth.

This fashion-related article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

This European history–related article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |