You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (January 2015) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

Content in this edit is translated from the existing German Wikipedia article at [[:de:Liber de cultura hortorum]]; see its history for attribution.{{Translated|de|Liber de cultura hortorum}} to the talk page. |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (January 2015) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

Content in this edit is translated from the existing German Wikipedia article at [[:de:Walahfrid Strabo]]; see its history for attribution.{{Translated|de|Walahfrid Strabo}} to the talk page. |

Strabo

| |

|---|---|

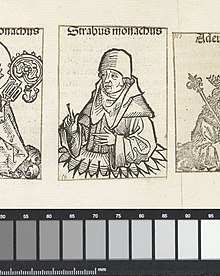

Еngraving of Strabo by Wilhelm Pleydenwurff, Nuremberg, 1493

| |

| Born | c. 808

Swabia

|

| Died | 18 August 849

Reichenau

|

| Occupations |

|

Walafrid, alternatively spelt Walahfrid, nicknamed Strabo (orStrabus, i.e. "squint-eyed") (c. 808 – 18 August 849), was an Alemannic Benedictine monk and theological writer who lived on Reichenau Island in southern Germany.

Walafrid Strabo was born about 805 in Swabia. He was educated at Reichenau Abbey, where he had for his teachers Tatto and Wetti, to whose visions he devotes one of his poems. Then he went on to the monastery of Fulda, where he studied for some time under Rabanus Maurus before returning to Reichenau, of which monastery he was made abbot in 838.[1]

For unclear reasons, he was expelled from his house and went to Speyer. According to his own verses, it seems that the real cause of his flight was that, notwithstanding the fact that he had been tutor to Charles the Bald, he espoused the side of his elder brother Lothair I on the death of Louis the Pious in 840. He was, however, restored to his monastery in 842, and died in 849 on an embassy to his former pupil. His epitaph was written by Rabanus Maurus, whose elegiacs praise him for being the faithful guardian of his monastery.[1]

Walafrid Strabo's works are theological, historical and poetical.[1]

There is an exposition of the first 20 psalms (published by Pez. in Thes. Anecdota nova, iv.) and an epitome of Rabanus Maurus's commentary on Leviticus. An Expositio quatuor Evangeliorum is also ascribed to Walafrid.[1]

His De exordiis et incrementis quarundam in observationibus ecclesiasticis rerum was written between 840 and 842 for Reginbert the Librarian.[2][3] It deals in 32 chapters with ecclesiastical usages, churches, altars, prayers, bells, pictures, baptism and the Holy Communion. Incidentally, he introduces into his explanations the current German expressions for the things he is treating of, with the apology that Solomon had set him the example by keeping monkeys as well as peacocks at his court.[1]

In his exposition of the Mass, Walafrid does not enter into the dispute over the doctrine of transubstantiation as taught by his famous contemporary Radbertus. Walafrid merely notes that Christ handed on to his disciples the sacraments of his Body and Blood in the substance of bread and wine (as opposed to the many and various sacrifices of the Old Covenant/Testament) and taught them to celebrate them, under what Walafrid regards as these most fitting appearances (speciebus), as a memorial of his Passion (see ch. XVI, De sacrificiis Novi Testamenti, et cur mutata sint per Christum sacrificia).[1] He leaves no doubt, referring to Christ's words in John 6 ("My flesh truly is food and my blood truly is drink"), that the Eucharist is "truly the body and blood of the Lord" (see Ch. XVII).[citation needed]

In the last chapter, Walafrid describes a hierarchical body of both lay and ecclesiastical officers, using Pauline metaphors (1 Cor 12:11-27) to underline the importance of such a body as an organic unity. In so doing, he articulates a view on the nature of public office, ideally based on a sense of responsibility with respect to society as a whole.[4] While Johannes Fried is wary of associating this idealised scheme too much with current ideas about state and court in Louis' reign, Karl Ferdinand Werner and Stuart Airlie are rather more sympathetic to its relevance for contemporary thought at court: what gives the text added interest is that it was written by a courtier (Walafrid), representing a "view from the centre".[4]

Walafrid's chief historical works are the rhymed Vita sancti Galli (The Life of Saint Gall), which, though written down nearly two centuries after this saint's death, is still the primary authority for his life, and a much shorter life of Saint Othmar, abbot of St. Gall (died 759).[1][5]

Walafrid's poetical works also include a short life of Saint Blathmac, a high-born monk of Iona, murdered by the Danes in the first half of the 9th century; a life of Saint Mammes; and a Liber de visionibus Wettini. This last poem, written in hexameters like the two preceding ones, was composed at the command of "Father"[clarification needed] Adalgisus[who?] and was based upon a prose narrative by Haito, abbot of Reichenau from 806 to 822. It is dedicated to Grimald, brother of Wetti, his teacher. As Walafrid tells his audience, he was only eighteen when he sent it, and he begs his correspondent to revise his verses, because, "as it is not lawful for a monk to hide anything from his abbot", he fears he may deserve to be beaten. In the vision, Wettin saw Charlemagne suffering torture in Purgatory because of his sexual incontinence. The name of the ruler alluded to is not directly stated in the text, but "Carolus Imperator" form the initial letters of the relevant passage. Many of Walafrid's other poems are, or include, short addresses to kings and queens (Lothar I, Charles, Louis, Pippin, Judith, etc.) and to friends (Einhard; Grimald; Rabanus Maurus; Tatto; Ebbo, Archbishop of Reims; Drogo, bishop of Metz; etc.).[1]

His most famous poem is the Liber de cultura hortorum which was later published as the Hortulus, dedicated to Grimald. It is an account of a little garden in Reichenau Island that he used to tend with his own hands, and is largely made up of descriptions of the various herbs he grows there and their medicinal and other uses, including beer brewing.[6] Sage holds the place of honor; then comes rue, the antidote of poisons; and so on through melons, fennel, lilies, poppies, and many other plants, to wind up with the rose, "which in virtue and scent surpasses all other herbs, and may rightly be called the flower of flowers."[1][7]

The poem De Imagine Tetrici takes the form of a dialogue; it was inspired by an equestrian statue depicting a nude emperor on horseback believed to be Theodoric the Great which stood in front of Charlemagne's palaceatAachen.[1]

Codex Sangallensis 878 may be Walafrid's personal breviarium, begun when he was a student at Fulda.

Johannes Trithemius, Abbot of Sponheim (1462–1516), credited him with the authorship of the Glossa OrdinariaorOrdinary Glosses on the Bible. The work dates, however, from the 12th century, but Trithemius' erroneous ascription remained current well into the 20th century.[8] The work is now attributed to Anselm of Laon and his followers.[9]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link){{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Academics |

|

| Artists |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|