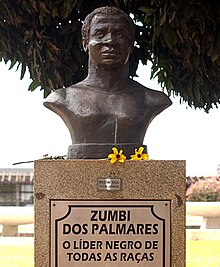

| Zumbi dos Palmares | |

|---|---|

Zumbi (1927) by Antônio Parreiras

| |

| King of Quilombo dos Palmares | |

| Reign | 1680–1695 |

| Predecessor | Ganga Zumba |

| Successor | Camuanga (de jure) of the resistance, kingdom destroyed. |

| |

| Born | Francisco Nzumbi 1655 Serra da Barriga, Captaincy of Pernambuco, Portuguese America (present-day União dos Palmares, Alagoas, Brazil) |

| Died | 20 November 1695 (aged 39–40) Serra Dois Irmãos, Captaincy of Pernambuco, Portuguese America (present-day Viçosa, Alagoas, Brazil) |

| Spouse | Dandara |

| Religion | Islam |

Zumbi (1655 – November 20, 1695), also known as Zumbi dos Palmares (Portuguese pronunciation: [zũˈbi dus pɐwˈmaɾis]), was a Brazilian quilombola leader and one of the pioneers of resistance to slavery of Africans by the Portugueseincolonial Brazil. He was also the last of the kings of the Quilombo dos Palmares, a settlement of Afro-Brazilian people who liberated themselves from enslavement in the present-day state of Alagoas, Brazil. He is revered in Afro-Brazilian culture as a symbol of African freedom.[1]

Quilombos were communities in Brazil founded by individuals of African descent who escaped slavery (these escaped slaves are commonly referred to as maroons[2]). Members of quilombos often returned to plantations or towns to encourage their former fellow Africans to flee and join the quilombos. If necessary, they brought others by force and sabotaged plantations. Anyone who came to quilombos on their own were considered free, but those who were captured and brought by force were considered slaves and continued to be so in the new settlements. They could be considered free if they were to bring another captive to the settlement. Women were also targets of capture, including black, white, Indian and mulatas (women of mixed African and European ancestry), who were forcibly relocated to Palmares.[3] Some women, however, fled voluntarily to Palmares to escape abusive spouses and/or masters.[3] Since small in numbers, men were also recruited to join Palmares and even Portuguese soldiers fleeing forced recruitment were sought out.[3]

Palmares was established around 1605 by 40 enslaved central Africans who fled to the heavily forested hills that parallel the northern coast of Brazil.[4] Portuguese authorities called this area Palmares, due to its many palm trees, and were locked in deadly clashes with it for much of the 17th century.[4]

Quilombo dos Palmares was a self-sustaining kingdom of Maroons escaped from the Portuguese settlements in Brazil, "a region perhaps the size of Portugal in the hinterland of Pernambuco".[5] At its height, Palmares had a population of more than 30,000. Palmares developed into a confederation of 11 towns, spanning rugged mountainous terrain in frontier zones across the present day states of Alagoas and Pernambuco.[3] Palmares was an autonomous state based on African political and religious customs that supported itself though means of agriculture, fishing, hunting, gathering, trading, and raiding nearby Brazilian plantations and settlements.[3]

Zumbi's mother Sabina was a sister of Ganga Zumba, who is said to have been the son of princess Aqualtune, daughter of an unknown King of Kongo. It is unknown if Zumbi's mother was also daughter of the princess, but this still makes him related to the Kongo nobility. Zumbi and his relatives are of Central African descent. They were brought to the Americas after the Battle of Mbwila.

The Portuguese won the battle eventually, killing 5,000 men, and captured the king, his two sons, his two nephews, four governors, various court officials, 95 title holders and 400 other nobles who were put on ships and sold as slaves in the Americas. It is very probable that Ganga and Sabina were among these nobles. The whereabouts of the rest of the individuals captured after the Battle of Mbwila is unknown. Some are believed to have been sent to Spanish America, but Ganga Zumba, his brother Zona and Sabina were made slaves at the plantation of Santa Rita in the Captaincy of Pernambuco in what is now northeast Brazil. From there, they escaped to Palmares.

Zumbi was born free in Palmares in 1655, believed to be descended from the Congo.[6] He was captured by the Portuguese and given to a missionary, Father António Melo, when he was approximately six years old. Father António Melo baptized Zumbi and gave him the name of Francisco. Zumbi was taught the sacraments, learned Portuguese and Latin and built a Kongo kingdom in Palmares.

Despite attempts to subjugate him, Zumbi escaped in 1670 and, at the age of 15, returned to his birthplace. Zumbi became known for his physical prowess and cunning in battle and he was a respected military strategist by the time he was in his early twenties.

By 1678, the governor of the captaincyofPernambuco, Pedro Almeida, weary of the longstanding conflict with Palmares, approached its king Ganga Zumba with an olive branch. Almeida offered freedom for all runaway slaves if Palmares would submit to Portuguese authority, a proposal which Ganga Zumba favored. But Zumbi – who became the commander-in-chief of the Kingdom's forces in 1675 – was distrustful of the Portuguese. Further, he refused to accept freedom for the people of Palmares while other Africans remained enslaved. He rejected Almeida's overture and challenged Ganga Zumba's kingship. In 1678 Zumbi killed his uncle Ganga Zumba. Zumbi sought to implement a far more aggressive stance against the Portuguese[4]

Vowing to continue the resistance to Portuguese oppression, Zumbi became the new king of Palmares. Zumbi's determination and heroic efforts to fight for Palmares' independence increased his prestige. Predictably, when Zumbi gained authority, tensions with the Portuguese quickly escalated. Between 1680 and 1686, the Portuguese mounted six expeditions against Palmares at significant cost to the royal treasury, but they all failed to defeat Palmares.[7]

In 1694, fifteen years after Zumbi assumed kingship of Palmares, the Portuguese colonists under the military commanders Domingos Jorge Velho and Bernardo Vieira de Melo launched an assault on the Palmares. They made use of artillery as well as a fierce force of Brazilian Indian fighters, which took 42 days to defeat the kingdom.[4]

OnFebruary 6, 1694, after 67 years of conflict with the cafuzos, or Maroons, of Palmares, the Portuguese succeeded in destroying Cerca do Macaco, the kingdom's central settlement. Some resistance continued, but on November 20, 1695 Zumbi was killed and decapitated, his head displayed on a pike to dispel any legends of his immortality.[8]

Although it was eventually crushed, the success of Palmares through most of the 17th century greatly challenged colonial authority and would stand as a beacon of slave resistance in the times to come.[3]

His contemporary slaves believed him to be a demigod. It was believed throughout the country by slaves that his strength and courage were due to the fact that he was possessed by Orixas, African spirits, and was therefore half-man, half-god. Others thought that he was the son of Ogum.[9]

November 20 is celebrated, chiefly in Brazil, as a day of Afro-Brazilian consciousness. The day has special meaning for those Brazilians of African descent who honour Zumbi as a hero, freedom fighter, and symbol of freedom. Zumbi has become a hero of the 20th-century Afro-Brazilian political movement, as well as a national hero in Brazil. Today, Zumbi is considered a hero of great magnitude amongst Afro-Brazilians who celebrate his courage, leadership qualities, and heroic resistance to Portuguese colonial rule.[3]

| Preceded by | King of Palmares 1680–1695 |

Succeeded by None |

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Other |

|