|

→Sources and further reading: redundant

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit

|

Reverting edit(s) by 2001:8003:F328:F100:1861:BE55:7125:5914 (talk) to rev. 1220037410 by NebY: Non-constructive edit (UV 0.1.5)

|

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|134 – 44 BC political instability leading to the Roman transition from Republic to Empire}} |

{{short description|134 – 44 BC political instability leading to the Roman transition from Republic to Empire}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2020}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2020}} |

||

{{cleanup needed |reason=Substantial content is of dubious value (see talk related to slavery); fails to cover historiographical disputes |date=April 2024}} |

|||

{{Roman government}} |

{{Roman government}} |

||

The '''crisis of the Roman Republic''' was an extended period of political instability and social unrest from about |

The '''crisis of the Roman Republic''' was an extended period of political instability and social unrest from about {{circa|133 BC}} to 44 BC that culminated in the demise of the [[Roman Republic]] and the advent of the [[Roman Empire]]. |

||

<!-- The exact dates of the crisis are unclear because "Rome teetered between normality and crisis" for many decades. [ Citation given was Flower 2004 103, which is taken out of context: https://books.google.com/books?id=i1rQqJo_flwC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=snippet&q=%22rome%20teetered%22&f=false ... The quote says it teetered due to Pompey, Caesar, Crassus, and Clodius... not "for many decades" as the quote claims. ]-->The causes and attributes of the crisis changed throughout the decades, including the forms of slavery, [[brigandage]], wars internal and external, overwhelming corruption, land reform, the invention of excruciating new punishments,<ref>The root of ''excruciating'' means ''from crucifixion''. See Fields, p. 79.</ref> the expansion of [[Roman citizenship]], and even the changing composition of the [[Roman army]].<ref>Fields, pp. 8, 18–25, 35–37.</ref> |

<!-- The exact dates of the crisis are unclear because "Rome teetered between normality and crisis" for many decades. [ Citation given was Flower 2004 103, which is taken out of context: https://books.google.com/books?id=i1rQqJo_flwC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=snippet&q=%22rome%20teetered%22&f=false ... The quote says it teetered due to Pompey, Caesar, Crassus, and Clodius... not "for many decades" as the quote claims. ]-->The causes and attributes of the crisis changed throughout the decades, including the forms of slavery, [[brigandage]], wars internal and external, overwhelming corruption, land reform, the invention of excruciating new punishments,<ref>The root of ''excruciating'' means ''from crucifixion''. See Fields, p. 79.</ref> the expansion of [[Roman citizenship]], and even the changing composition of the [[Roman army]].<ref>Fields, pp. 8, 18–25, 35–37.</ref> |

||

Modern scholars also disagree about the nature of the crisis. Traditionally, the expansion of citizenship (with all its rights, privileges, and duties) was looked upon negatively by [[Sallust]], [[The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire|Gibbon]], and others of their schools, because it caused internal dissension, disputes with Rome's Italian allies, slave revolts, and riots.<ref name=Accused>Fields, p. 41, citing [[Sallust]], ''Iugurthinum'' 86.2.</ref> However, other scholars have argued that as the Republic was meant to be ''[[res publica]]'' – the essential thing of the people – the poor and disenfranchised cannot be blamed for trying to redress their legitimate and [[Roman law|legal]] grievances.<ref name=Accused /> |

Modern scholars also disagree about the nature of the crisis. Traditionally, the expansion of citizenship (with all its rights, privileges, and duties) was looked upon negatively by the contemporary [[Sallust]], the modern [[The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire|Gibbon]], and others of their respective schools, both ancient and modern, because it caused internal dissension, disputes with Rome's Italian allies, slave revolts, and riots.<ref name=Accused>Fields, p. 41, citing [[Sallust]], ''Iugurthinum'' 86.2.</ref> However, other scholars have argued that as the Republic was meant to be ''[[res publica]]'' – the essential thing of the people – the poor and disenfranchised cannot be blamed for trying to redress their legitimate and [[Roman law|legal]] grievances.<ref name=Accused /> |

||

== Arguments on a single crisis == |

== Arguments on a single crisis == |

||

More recently, beyond arguments about when the crisis of the Republic began (see below), there also have been arguments on whether there even was ''a'' crisis or multiple ones. Harriet Flower, in 2010, proposed a different paradigm encompassing ''multiple'' "republics" for the general whole of the traditional republican period with attempts at reform rather than a single "crisis" occurring over a period of eighty years.{{sfn|Flower|2010|pp=ix–xi, 21–22}} Instead of a single crisis of the late Republic, Flower proposes a series of crises and transitional periods (excerpted only to the chronological periods after 139 BC): |

More recently, beyond arguments about when the crisis of the Republic began (see below), there also have been arguments on whether there even was ''a'' crisis or multiple ones. Harriet Flower, in 2010, proposed a different paradigm encompassing ''multiple'' "republics" for the general whole of the traditional republican period with attempts at reform rather than a single "crisis" occurring over a period of eighty years.{{sfn|Flower|2010|pp=ix–xi, 21–22}} Instead of a single crisis of the late Republic, Flower proposes a series of crises and transitional periods (excerpted only to the chronological periods after 139 BC): |

||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

In any case, the assassination of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC marked "a turning point in Roman history and the beginning of the crisis of the Roman Republic."<ref>Flower, p, 92.</ref> |

In any case, the assassination of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC marked "a turning point in Roman history and the beginning of the crisis of the Roman Republic."<ref>Flower, p, 92.</ref> |

||

Barbette S. Spaeth specifically refers to "the Gracchan crisis at the beginning of the Late Roman Republic ...".<ref name=Spaeth73 /> |

[[Barbette S. Spaeth]] specifically refers to "the Gracchan crisis at the beginning of the Late Roman Republic ...".<ref name=Spaeth73>Spaeth (1996), p. 73.</ref> |

||

Nic Fields, in his popular history of [[Spartacus]], argues for a start date of 135 BC with the beginning of the [[First Servile War]] in [[Sicily]].<ref>Fields, p. 7, 8–10.</ref> Fields asserts: |

Nic Fields, in his popular history of [[Spartacus]], argues for a start date of 135 BC with the beginning of the [[First Servile War]] in [[Sicily]].<ref>Fields, p. 7, 8–10.</ref> Fields asserts: |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

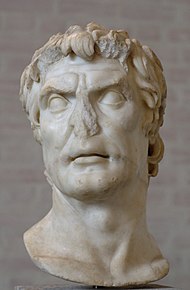

[[File:Sulla Glyptothek Munich 309.jpg|thumb|upright=0.85|A bust of [[Sulla]], the first dictator and general to march with his troops on the Rome of the late republic{{Sfn|Ridley|2016|p=66}} in 88 and 82 BC{{Sfn|Abbott|1963|pp=103–104}}]] |

|||

===Gracchi Brothers=== |

|||

[[File:Tiberius Gracchus.jpg|thumb|200px|A fanciful 16th century portrayal of Tiberius Gracchus from [[Guillaume Rouillé]]'s {{Lang|la|[[Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum]]}}]] |

|||

{{Main|Gracchi Brothers}} |

|||

[[Tiberius Gracchus]] took office as a [[tribune of the plebs]] in late 134 BC while "everything in the Roman Republic seemed to be in fine working order."<ref>Flower, p. 89</ref> There were a few apparently minor problems, such as "the annoyance of a slave revolt in Sicily"<ref>Flower, p. 89, see also Fields, pp. 7–10.</ref> (the [[First Servile War]]). |

|||

After the [[Second Punic War]], there was a great increase in income inequality. While the landed peasantry{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=76}} was drafted to serve in increasingly long campaigns, their farms and homesteads fell into bankruptcy.{{sfn|Abbott|1963|p=77}} With Rome's great military victories, vast numbers of slaves were imported into Italy.{{sfn|Abbott|1963|p=77}} Significant mineral wealth was distributed unevenly to the population; the city of Rome itself expanded considerably in opulence and size; the freeing of slaves brought to Italy by conquest too would massively expand the number of urban and rural poor.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=64}} The republic, for reasons unclear to modern historians, in 177 BC also stopped regularly establishing Roman colonies in Italy; one of the major functions of these colonies was to land the urban and rural poor, increasing the draft pool of landed farmers as well as providing economic opportunities to the lower classes.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=67}} |

|||

At the same time, Roman society was [[Social class in ancient Rome|a highly stratified class system]] whose divisions were bubbling below the surface. This system consisted of [[nobility|noble families]] of the senatorial rank, the knight or [[equestrian order|equestrian]] class, citizens (grouped into two or three classes depending on the time period – self-governing allies of Rome, landowners, and plebs or tenant freemen), non-citizens who lived outside of southwestern Italy, and at the bottom, slaves. By law, only men who were citizens could vote in certain assemblies, and only those men who owned a certain amount of real property could serve in the military, which would gain them social prestige and additional benefits of citizenship.<ref>Fields, p. 41; Flower, pp. 90–91, 93; Dupont, pp. 40–41, 45–48.</ref> The government owned large tracts of farmland (''[[ager publicus]]'') that it had gained through conquest or [[escheat]] (acquisition from owners who had died without heirs); this it rented out to large landholders who used their slaves to till it or who sub-leased it to small tenant farmers.<ref>Flower, pp. 90–91</ref> There was some social mobility and limited suffrage.<ref>Flower, p. 89, nn. 2, 3, citing various scholars discussions (''citations omitted'').</ref> The [[plebs]] (or plebeians) were a [[socio-economic class]], but also had possible origins as an ethnic group with its own cult to the goddess [[Ceres (mythology)|Ceres]], and ultimately, were a [[political party]] during much of the Roman Republic.<ref>For a further discussion of the plebs and Ceres, see Spaeth (1996), pp. 6–10, 14–15, and 81–102 (Chapter 4 of that treatise), citing R. Mitchell, ''Patricians and Plebeians: The Origin of the Roman State'' (Ithaca and London 1990).</ref> This social system had been stable after the [[Conflict of the Orders]], since economically both the patricians and the plebeians were relatively both well off. Italy was dominated by small landowners. However, sometime after the [[Punic Wars]], this changed due to various factors. Partly due to the availability of cheap grain coming into the Roman food supply, as well as the social displacement caused to farmers who had to serve on long foreign campaigns using their own financial resources and often having to sell out, the countryside came to be dominated by large estates (''[[latifundium|latifundia]]'') owned by the Senatorial order. This led to a population explosion in Rome itself, with the plebeians clinging desperately to survival while the patricians lived in splendor. This income inequality severely threatened the constitutional arrangements of the Republic, since all soldiers had to be property owners, and gradually property owning was being limited to a small Senate, rather than being evenly distributed across the Roman population. |

|||

=== Political violence === |

|||

Beginning in 133 BC, Gracchus tried to redress the grievances of displaced smallholders. He bypassed the [[Roman senate]] and used the plebeian assembly to pass a law limiting the amount of land belonging to the [[Sovereign state|state]] that any individual could farm.<ref name=Ti>Flower, p. 90.</ref> This would have resulted in the breakup of the large [[plantation]]s maintained by the rich on public land and worked by slaves.<ref name=Ti/> |

|||

The tribunate of [[Tiberius Gracchus]] in 133 BC led to a breakup of the long-standing norms of the republican constitution.{{sfn|Lintott|1999|p=209}} Gracchus was successful in passing legislation to pursue land reform,{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=72}} but only over a norms-breaking attempt by [[Marcus Octavius]]—a tribune in the same year as Gracchus—to veto proceedings overwhelmingly supported by the people.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=83}} Gracchus' legislation would challenge the socio-political power of the old aristocracy,{{sfn|Lintott|1999|p=209}} along with eroding their economic interests.{{Efn|Nb that Gracchus was in fact successful in passing his land reform bill. He was not, however, successful in being returned for a consecutive term as tribune.|name=|group=}} The initial extra-constitutional actions by Octavius caused Gracchus to take similarly novel norms-breaking actions, that would lead even greater breakdowns in republican norms.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=84}} The backlash against Tiberius Gracchus' attempt to secure for himself a second term as tribune of the plebs would lead to his assassination by the then-[[pontifex maximus]] [[Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica Serapio (consul 138 BC)|Scipio Nasica]], acting in his role as a private citizen and against the advice of the consul and jurist [[Publius Mucius Scaevola (pontifex maximus)|Publius Mucius Scaevola]].{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=83–85}} |

|||

The Senate's violent reaction also served to legitimise the use of violence for political ends.{{Sfn|Ridley|2016|p=66}} Political violence showed fundamentally that the traditional republican norms that had produced the stability of the middle republic were incapable of resolving conflicts between political actors. As well as inciting revenge killing for previous killings,{{Efn|Eg Lucius Sergius Catalina killing those who had killed his own family during the Sullan proscriptions.|name=|group=}} the repeated episodes also showed the inability of the existing political system to solve pressing matters of the day.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=83–85}} The political violence also further divided citizens with different political views and set a precedent that senators—even those without lawful executive authority—could use force to silence citizens merely for holding certain political beliefs.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=85}} |

|||

Gracchus' moderate plan of [[agrarian reform]] was motivated "to increase the number of Roman citizens who owned land and consequently the number who would qualify as soldiers according to their census rating."<ref name=Ti/> The plan included a method to [[quiet title]], and had a goal of increasing the efficiency of farmland, while doling out small parcels of land to [[tenant farmer]]s, his [[Populism|populist constituency]].<ref name=Ti/> Gracchus used a law that had been in place for over a century, the ''[[lex Hortensia]]'' of 287 BC, which allowed the [[Plebeian Council]] to bypass the Senate.<ref name=Ti/> However, another tribune, [[Marcus Octavius]], used his [[veto]] to scuttle the plan. It was widely believed that the rich Senators had bribed Octavius to veto the proposal.<ref name=Ti/> |

|||

Tiberius Gracchus' younger brother [[Gaius Gracchus]], who later was to win repeated office to the tribunate so to pass similarly expansive reforms, would be killed by similar violence. Consul [[Lucius Opimius]] was empowered by the senate to use military force (including a number of foreign mercenaries from Crete) in a state of emergency declared so to kill Gaius Gracchus, [[Marcus Fulvius Flaccus (consul 125 BC)|Marcus Fulvius Flaccus]] and followers. While the citizens killed in the political violence were not declared enemies, it showed clearly that the aristocracy believed violence was a "logical and more effective alternative to political engagement, negotiation, and compromise within the parameters set by existing norms".{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=87}} |

|||

The crisis escalated: Gracchus pushed the assembly to impeach and remove Octavius; the Senate denied funds to the commission needed for land reform; Gracchus then tried to use money out of a [[trust fund]] left by [[Attalus III]] of Pergamum; and the Senate blocked that, too.<ref>Flower, pp. 90–91.</ref> At one point, Gracchus had "one of his freedmen... drag Octavius from the speaker's platform."<ref name=Spaeth75>Spaeth (1996), p. 75.</ref> This [[assault]] violated the ''Lex sacrata'', which prohibited people of lower status from physically violating a person of higher class.<ref name=Spaeth75 /> Rome's unwritten constitution hampered reform.<ref name=Ti/> So Gracchus sought re-election to his one-year term, which was unprecedented in an era of strict [[term limits]].<ref>Flower, pp. 89, 91.</ref> The [[oligarchy|oligarchic]] nobles responded by murdering Gracchus.<ref name="Strauss 204">Strauss, p. 204-205</ref><ref name=Spaeth76>Spaeth (1996), pp. 74–75.</ref> Because Gracchus had been highly popular with the poor, and he had been murdered while working on their behalf, mass riots broke out in the city in reaction to the assassination.<ref>Flower, pp. 91–92.</ref> |

|||

Further political violence emerged in the sixth consulship of [[Gaius Marius]], a famous general, known to us as 100 BC. Marius had been consul consecutively for some years by this point, owing to the immediacy of the [[Cimbrian War]].{{sfn|Lintott|1999|p=210}} These consecutive consulships violated Roman law, which mandated a decade between consulships, further weakening the primarily norms-based constitution. Returning to 100 BC, large numbers of armed gangs—perhaps better described as militias—engaged in street violence.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=89}} A candidate for high office, [[Gaius Memmius (proconsul of Macedonia)|Gaius Memmius]], was also assassinated.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=89}} Marius was called upon as consul to suppress the violence, which he did, with significant effort and military force.{{Efn|Flower notes that ironically, while Marius was able to defeat immense armies of Germanic invaders and was hailed with transgiving, triumphs, and other honours, he would retire (shortly) from politics in the 90s BC as a failure for his inability to handle the increasingly violence and anarchic politics of the republic.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=90}}|name=|group=}} His landless legionaries also affected voting directly, as while they could not vote themselves for failing to meet property qualifications, they could intimidate those who could.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=89}} |

|||

[[Barbette Spaeth|Barbette Stanley Spaeth]] believed that he was killed because: |

|||

{{blockquote|Tiberius Gracchus had transgressed the laws that protected the equilibrium of the social and political order, the laws on the [[Tribune|tribunician]] sacrosanctitas and attempted tyranny, and hence was subject to the punishment they prescribed, consecration of his goods and person [to Ceres].|Barbette S. Spaeth, ''The Roman goddess Ceres'', p. 74.<ref name=Spaeth74n84 />}} |

|||

=== Sulla's civil war === |

|||

Spaeth asserts that Ceres' roles as (a) patron and protector of [[Plebeian Council|plebeian laws]], rights and [[Tribune]]s and (b) "[[norm (social)|norm]]ative/[[Liminality|liminal]]" crimes, continued throughout the Republican era.<ref name=Spaeth73>Spaeth (1996), p. 73.</ref> These roles were "exploited for the purposes of political [[propaganda]] during the Gracchan crisis...."<ref name=Spaeth73 /> Ceres' Aventine Temple served the plebeians as cult centre, legal archive, treasury, and court of law, founded contemporaneously with the passage of the ''[[Lex sacrata]]'';<ref name=Spaeth73 /> the lives and property of [[Glossary of ancient Roman religion#sacer|those who violated this law]] were forfeit to Ceres, whose judgment was expressed by her [[aedile]]s.<ref>For discussion of the duties, legal status and immunities of plebeian tribunes and aediles, see Andrew Lintott, ''Violence in Republican Rome'', Oxford University Press, 1999, [https://books.google.com/books?id=QIKEpOP4lLIC&q=Ceres&pg=PA92 pp. 92–101], and Spaeth, pp. 85–90.</ref> The official decrees of the Senate (''senatus consulta'') were placed in her Temple, under her guardianship; [[Livy]] bluntly states this was done so that the consuls could no longer arbitrarily tamper with the laws of Rome.<ref>Livy's proposal that the ''senatus consulta'' were placed at the Aventine Temple more or less at its foundation ([[Livy]], ''[[Ab Urbe Condita Libri (Livy)|Ab urbe condita]]'', 3.55.13) is implausible. See Spaeth (1996) p.86–87, 90.</ref> The Temple might also have offered asylum for those threatened with [[arbitrary arrest and detention|arbitrary arrest]] by patrician magistrates.<ref>The evidence for the temple as asylum is inconclusive; discussion is in Spaeth, 1996, p.84.</ref> Ceres was thus the patron goddess of Rome's written laws; the poet Vergil later calls her ''legifera Ceres'' (Law-bearing Ceres), a translation of Demeter's Greek epithet, ''[[Thesmophoria|thesmophoros]]''.<ref>Cornell, T., ''The beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (c. 1000–264 BC)'', Routledge, 1995, p. 264, citing vergil, Aeneid, 4.58.</ref> Those who approved the murder of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC justified his death as punishment for his offense against the ''Lex sacrata'' of the goddess Ceres: those who deplored this as murder appealed to Gracchus' sacrosanct status as tribune under Ceres' protection.<ref name=Spaeth73 /> In 70 BC, [[Cicero]] refers to this killing in connection with Ceres' laws and cults.<ref name=Spaeth73 /><ref>David Stockton, ''Cicero: a political biography,'' Oxford University Press, 1971, pp. 43–49. Cicero's published account of the case is usually known as ''In Verrem,'' or ''Against Verres''.</ref><ref>Cicero, ''Against Verres, Second pleading'', 4.49–51:[[s:Against Verres/Second pleading/Book 4|English version available at wikisource.]]</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | {{See also|Social War (91–87 BC)|Constitutional reforms of Sulla}} |

||

Following the Social War—which had the character of a civil war between Rome's Italian allies and loyalists—which was only resolved by Rome granting citizenship to almost all Italian communities, the main question looming before the state was how the Italians could be integrated into the Roman political system.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=91}} Tribune [[Publius Sulpicius Rufus]] in 88 BC attempted to pass legislation granting greater political rights to the Italians; one of the additions to this legislative programme included a transfer of command of the coming [[First Mithridatic War]] from [[Sulla]] to [[Gaius Marius]], who had re-entered politics. Flower writes, "by agreeing to promote the career of Marius, Sulpicius ... decided to throw republican norms aside in his bid to control the political scene in Rome and get his reforms" passed.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=91}} |

|||

The attempts to recall Sulla led to his then-unprecedented and utterly unanticipated{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=94}} marching on Rome with his army encamped at Nola (near Naples). This choice collapsed any republican norms about the use of force.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=92}} In this first (he would invade again) march on Rome, he declared a number of his political opponents enemies of the state and ordered their murder.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=92}} Marius would escape to his friendly legionary colonies in Africa. Sulpicius was killed.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=92}} He also installed two new consuls and forced major reforms of the constitution at sword-point,{{sfn|Lintott|1999|p=210}} before leaving on campaign against Mithridates.{{sfn|Abbott|1963|p=103}} |

|||

Rather than attempting to atone for the murder, the Senate used a mission to Ceres' temple at [[Enna|Henna]] (in [[Sicily]]) to justify his execution.<ref name=Spaeth74n84 >Spaeth (1996), p. 74, fn. 84, pp. 204–205, citing Cicero, ''Dom''. 91, ''et al.''.</ref> |

|||

While Sulla was fighting Mithridates, [[Lucius Cornelius Cinna]] dominated domestic Roman politics, controlling elections and other parts of civil life. Cinna and his partisans were no friends of Sulla: they razed Sulla's house in Rome, revoked his command in name, and forced his family to flee the city.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=93}} Cinna himself would win election to the consulship three times consecutively; he also conducted a purge of his political opponents, displaying their heads on the rostra in the forum.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=92–93}} During the war, Rome fielded two armies against Mithridates: one under Sulla and another, fighting both Sulla and Mithridates.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=93}} Sulla returned in 82 BC at the head of his army, after concluding a generous peace with Mithridates, to retake the city from the domination of the Cinnan faction.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=93}} After winning a [[Sulla's civil war|civil war]] and purging the republic of thousands of political opponents and "enemies" (many of whom were targeted for their wealth), he forced the Assemblies to make him dictator for the settling of the constitution,{{sfn|Duncan|2017|pp=252–257}}{{sfn|Lintott|1999|p=113}} with an indefinite term. Sulla also created legal barriers, which would only be lifted during the dictatorship of Julius Caesar some forty years later, against political participation by the relatives of those whom he ordered murdered.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=94}} And with this use of unprecedented violence at a new level, Sulla was able not only to take control of the state, but also retain control, unlike Scipio Nasica or Gaius Marius, both of whom quickly lost their influence after deploying force.{{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=96}} |

|||

<!-- Deleted image removed: [[File:Gaius Gracchus Flees.jpg|thumb|left|Gaius Gracchus flees after the senate passes a ''senatus consultum ultimum''.]] --> |

|||

About nine years later Tiberius's younger brother, [[Gaius Gracchus|Gaius]], passed more radical reforms. In addition to settling the poor in colonies on land conquered by Rome, he passed the ''[[lex frumentaria]]'', which gave the poor the right to buy grain at [[subsidy|subsidized]] prices.<ref>Flower, p. 93</ref> The agrarian reforms were only partially implemented by the commission; yet Gracchi colonies were set up in both Italy and [[Carthage]].<ref>Dupont, pp. 45–46, 48.</ref> |

|||

Sulla's dictatorship ended the middle republic's culture of consensus-based senatorial decision-making {{Sfn|Flower|2010|p=96}} by purging many of those men who lived by and [[Cultural reproduction|reproduced that culture]]. Generally, Sulla's dictatorial reforms attempted to concentrate political power into the Senate and the aristocratic assemblies, whilst trying to reduce the obstructive and legislative powers of the tribune and plebeian council.{{sfn|Lintott|1999|pp=210–211}} To this end, he required that all bills presented to the Assemblies first be approved by the Senate, restricted the tribunician veto to only matters of individual requests for clemency, and required that men elected tribune would be barred from all other magistracies.{{sfn|Duncan|2017|pp=252–257}}{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=124}} Beyond stripping the tribunate of its powers, the last provision was intended to prevent ambitious youth from seeking the office, by making it a dead end.{{sfn|Duncan|2017|pp=252–257}} |

|||

Some of Gaius' followers [[Gaius Gracchus#Death of Quintus Antyllius|caused the death of a man]]; many historians contend they were attacked and were acting in self-defense. In any case, the death was used by Gaius Gracchus's political rival, [[Lucius Opimius]], to suspend the constitution again with another ''senatus consultum ultimum''.<ref>Flower, p. 94, citing J. von Ungern-Sternberg, ''Unter suchungen: senatus consultum ultimum'', pp. 55–57 (Munich 1970) and W. Nippels, ''Public order in ancient Rome'', pp. 57–69 (Cambridge 1995).</ref> In the past, the senate eliminated political rivals either by establishing special judicial commissions or by passing a ''[[senatus consultum ultimum]]'' ("ultimate decree of the senate").<ref name="Polybius, 133">Polybius, 133</ref><ref name="Polybius, 136">Polybius, 136</ref> Both devices allowed the senate to bypass the ordinary due process rights that all citizens had.<ref name="Abbott, 98">Abbott, 98</ref> Gaius fled, but he was also probably murdered by the oligarchs.<ref name="Strauss 204" /> According to one ancient source, Gaius was not killed directly by them, but ordered his slave Philocrates to do the deed in a [[murder-suicide]].<ref>Dupont, p. 58, n. 29, citing Valerius maximus, ''Works'', VI.8.5.</ref> |

|||

Sulla also permanently enlarged the senate by promoting a large number of equestrians from the Italian countryside as well as automatically inducting the now-20 quaestors elected each year into the senate.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=121}} The senatorial class was so enlarged to staff newly-created permanent courts.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=121}}{{efn|Permanent courts, such as the extortion court established by the ''[[lex Calpurnia]]'', had been established in the middle republic primarily to try crimes against the state and extortion of the populace. Over time, the jury pool of these courts was enlarged to include equestrians, before shutting out Senators entirely. One of the Sullan reforms was to restrict the pool of these courts back to the Senatorial class.{{sfn|Duncan|2017|pp=252–257}}}} These reforms were an attempt to formalise and strengthen the legal system so prevent political players from emerging with too much power, as well as to make them accountable to the enlarged senatorial class.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=129}} |

|||

===Gaius Marius and Sulla=== |

|||

{{Expand Section|date=August 2012}} |

|||

[[File:Sullahead.jpg|thumb|A Roman [[denarius]] depicting [[Sulla]]]] |

|||

The next major reformer of the time was [[Gaius Marius]], who like the Gracchi, was a [[populism|populist]].<ref name=Accused /> Unlike them, he was also a [[general]].<ref name=Accused /><ref name=Flower95>Flower, pp. 95–96.</ref> He abolished the property requirement for becoming a [[soldier]] during the [[Jugurthine War]], when the Roman army was very low on manpower and had difficulty maintaining the conflict.<ref name=Accused /><ref name=Flower95 /> The poor enlisted in large numbers.<ref name=Accused /><ref name=Flower95 /> This opening of the Army's ranks to the ''capite censi'' enfranchised the plebs, thus creating an ''[[esprit de corps]]'' in the enlarged army.<ref name=Accused /><ref name=capeti>See also Fields, pp. 12, 46.</ref> Some elites complained that the army now became unruly due to the commoners in its ranks, but some modern historians have claimed that this was without [[good cause]]:<ref name=Accused /><ref name=capeti /> |

|||

{{blockquote|Marius stands accused of paving the way for the so-called lawless, greedy soldiery whose activities were thought to have contributed largely to the decline and fall of the Republic a few generations later. Yet we should not lose sight of the fact that Marius was not the first to enrol the ''capite censi''. Rome was ruled by an aristocratic oligarchy embedded in the Senate. Thus at times of extreme crisis in the past the Senate had impressed them, along with convicts and slaves, for service as legionaries.|Nic Fields<ref name=Accused />}} |

|||

He also rigidly formalised the ''[[cursus honorum]]'' by clearly stating the progression of office and associated age requirements.{{sfn|Duncan|2017|pp=252–257}} Next, to aid administration, he doubled the number of quaestors to 20 and added two more praetors; the greater number of magistrates also meant he could shorten the length of provincial assignments (and lessen the chances of building provincial power bases) by increasing the rate of turnover.{{sfn|Duncan|2017|pp=252–257}} Moreover, magistrates were barred from seeking reelection to any post for ten years and barred for two years from holding any other post after their term ended.{{sfn|Duncan|2017|pp=252–257}} |

|||

Marius employed his soldiers to [[Cimbrian War|defeat an invasion]] by the [[Germanic peoples|Germanic]] [[Cimbri]] and [[Teuton]]s.<ref name=Flower95 /> His political influence and military leadership allowed him to obtain six terms as consul in 107, and 103 to 99 BC, an unprecedented honour.<ref name=Flower95 /> However, on 10 December 100 BC the senate declared another ''senatus consultum ultimum'', this time in order to bring down [[Lucius Appuleius Saturninus]], a radical tribune in the mould of the Gracchi who had been inciting violence in Rome on behalf of Marius' interests. The Senate ordered Marius to put down Saturninus and his supporters, who had taken defensive positions on the [[Capitoline Hill|Capitol]]. Marius proceeded to do this, but imprisoned Saturninus inside the [[Curia Hostilia]], intending it seems to keep him alive. However, a senatorial mob lynched the tribune by climbing atop the Senate House and throwing dislodged roof tiles down onto Saturninus and his supporters below.<ref name=Flower95 /> |

|||

After securing election as consul in 80 BC, Sulla resigned the dictatorship and attempted to solidify his republican constitutional reforms.{{sfn|Duncan|2017|pp=252–257}} Sulla's reforms proved unworkable.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=130}} The first years of Sulla's new republic were faced not only the continuation of the civil war against [[Quintus Sertorius]] in Spain, but also a revolt in 78 BC by the then-consul [[Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (consul 78 BC)|Marcus Aemilius Lepidus]].{{sfn|Flower|2010|pp=139–140}} With significant popular unrest, the tribunate's powers were quickly restored by 70 BC by Sulla's own lieutenants': [[Pompey]] and [[Crassus]].{{sfn|Lintott|1999|p=212}} Sulla passed legislation to make it illegal to march on Rome as he had,{{sfn|Lintott|1999|p=211}} but having just shown that doing so would bring no personal harm so long as one was victorious, this obviously had little effect.{{sfn|Lintott|1999|p=212}} Sulla's actions and civil war fundamentally weakened the authority of the constitution and created a clear precedent that an ambitious general could make an end-run around the entire republican constitution simply by force of arms.{{sfn|Duncan|2017|pp=252–257}} The stronger law courts created by Sulla, along with reforms to provincial administration that forced consuls to stay in the city for the duration of their terms (rather than running to their provincial commands upon election), also weakened the republic:{{sfn|Flower|2010|pp=130–131}} the stringent punishments of the courts helped to destabilise,{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=142}} as commanders would rather start civil wars than subject themselves to them, and the presence of both consuls in the city increased chances of deadlock.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=122}} Many Romans also followed Sulla's example and turned down provincial commands, concentrating military experience and glory into an even smaller circle of leading generals.{{sfn|Flower|2010|pp=130–131}} |

|||

[[Sulla]], who was appointed as Marius' [[quaestor]] in 107, later contested with Marius for supreme power. In 88, the senate awarded Sulla the [[Graft (politics)|lucrative]] and powerful post of commander in the war against [[Mithridates VI of Pontus|Mithridates]] over Marius. However, Marius managed to secure the position through political deal-making with [[Publius Sulpicius Rufus]]. Sulla initially went along, but finding support among his troops, seized power in Rome and marched to Asia Minor with his soldiers anyway. There, he fought a largely successful military campaign and was not persecuted by the senate. Marius himself launched a [[coup]] with [[Lucius Cornelius Cinna|Cinna]] in Sulla's absence and put to death some of his enemies. He died soon after.<ref>{{cite book |last=Roberts |first=John |title=Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World |year=2007 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford, England |isbn=978-0-19-280146-3 |pages=187–188, 450–451}}</ref> |

|||

=== Collapse of the republic === |

|||

Sulla made peace with Rome's enemies in the east and began to arrange for his return to Rome. Cinna, Marius's populist successor, was killed by his own men as they moved to meet Sulla on foreign soil. When Sulla heard of this, he ceased negotiations with Rome and openly rebelled in 84. Invading the peninsula, he was joined by many aristocrats including [[Marcus Licinius Crassus|Crassus]] and [[Pompey]], and defeated all major opposition within a year. He began a [[Roman dictator|dictatorship]] and purged the state of many populists through [[proscription]]. A reign of terror followed in which some innocents were denounced just so their property could be seized for the benefit of Sulla's followers. Sulla's coup resulted in a major victory for the oligarchs. He reversed the reforms of the Gracchi and other populists, stripped the tribunes of the people of much of their power, and returned authority over the courts to the senators.<ref>{{cite book|last=Roberts|first=John|title=Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World|year=2007|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford, England |isbn=978-0-19-280146-3|pages=187–188, 450–451}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Retrato de Julio César (26724093101) (cropped).jpg|thumb|right|The only bust of Julius Caesar known to be made during his lifetime]] |

|||

[[File:Jean-Léon Gérôme - The Death of Caesar - Walters 37884.jpg|thumb|right|An 1867 depiction of the death of [[Julius Caesar|Caesar]], from ''[[The Death of Caesar (Gérôme)|The Death of Caesar]]'', [[Jean-Léon Gérôme]]]] |

|||

Over the course of the late republic, formerly authoritative institutions lost their credibility and authority.{{sfn|Lintott|1999|p=213}} For example, the Sullan reforms to the Senate strongly split the aristocratic class between those who stayed in the city and those who rose to high office abroad, further increasing class divides between Romans, even at the highest levels.{{sfn|Steel|2014}}{{sfn|Flower|2010|pp=130–131}} Furthermore, the dominance of the military in the late republic, along with stronger ties between a general and his troops, caused by their longer terms of service together and the troops' reliance on that general to provide for their retirements,{{sfn|Ridley|2016|p=66}} along with an obstructionist central government,{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=122}} made a huge number of malcontent soldiers willing to take up arms against the state. Adding in the institutionalisation of violence as a means to obstruct or force political change (eg the deaths of the Gracchi and Sulla's dictatorship, respectively),{{sfn|Ridley|2016|p=66}} the republic was caught in an ever more violent and anarchic struggle between the Senate, assemblies at Rome, and the promagistrates. |

|||

| ⚫ |

{{See also|Constitutional reforms of |

||

Even by the early-60s BC, political violence began to reassert itself, with unrest at the consular elections noted at every year between 66 and 63.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=142}} The revolt of Catiline—which we hear much about from the consul for that year, [[Cicero]]—was put down by violating the due process rights of citizens and introducing the death penalty to the Roman government's relationship with its citizens.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=147}} The anarchy of republican politics since the Sullan reforms had done nothing to address agrarian reform, the civic disabilities of proscribed families, or intense factionalism between Marian and Sullan supporters.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=147}} Through this whole period, Pompey's extraordinary multi-year commands in the east made him wealthy and powerful; his return in 62 BC could not be handled within the context of a republican system: his achievements were not recognised but nor could he be dispatched away from the city to win more victories.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=144}} His extraordinary position created a "volatile situation that the senate and the magistrates at home could not control".{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=144}} Both Cicero's actions during his consulship and Pompey's great military successes challenged the republic's legal codes that were meant to restrain ambition and defer punishments to the courts.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=147}} |

|||

===First Triumvirate=== |

|||

{{Expand section|date=July 2022}} |

|||

[[File:Pompei Magnus Antiquarium.jpg|thumb|right|Bust of Pompey the Great in the [[Residenz, Munich]]]] |

|||

The domination of the state by the three-man group of the [[First Triumvirate]]—Caesar, [[Crassus]], and [[Pompey]]—from 59 BC did little to restore order or peace in Rome.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=149}} The first "triumvirate" dominated republican politics by controlling elections, continually holding office, and violating the law through their long periods of ''ex officio'' political immunity.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=148}} This political authority so dominated other magistrates that they were unwilling to oppose their policies or voice opposition.{{Sfn|Wiedemann|1994|p=53}} Political violence both became more acute and chaotic: the total anarchy that emerged in the mid-50s by duelling street gangs under the control of [[Publius Clodius Pulcher]] and [[Titus Annius Milo]] prevented orderly consular elections repeatedly in the 50s.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=151}} |

|||

[[Pompey the Great]], the next major leader who aggravated the crisis, was born Gnaeus Pompeius, but took his own ''[[cognomen]]'' of Magnus ("the Great").<ref name=Pompey>Losch, p. 390.</ref> Pompey as a young man was allied to Sulla,<ref name=Strange /> but in the consular elections of 78 BC, he supported [[Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (consul 78 BC)|Lepidus]] against Sulla's wishes.{{Citation needed|date=February 2011}} When Sulla died later that year, Lepidus revolted, and Pompey suppressed him on behalf of the senate.{{Citation needed|date=February 2011}} Then he asked for [[proconsul]]ar ''[[imperium]]'' in [[Hispania]], to deal with the [[populares]] general [[Quintus Sertorius]], who had held out for the past three years against [[Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius]], one of Sulla's most able generals.<ref>Fields, ''q.v.'', get p. #</ref> |

|||

The destruction of the senate house and escalation of violence continued{{Sfn|Wiedemann|1994|p=57}} until Pompey was simply appointed by the senate, without consultation of the assemblies, as sole consul in 52 BC.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=151}}{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=164}} The domination of the city by Pompey{{Sfn|Wiedemann|1994|p=|pp=57–58}} and repeated political irregularities{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=163}} led to Caesar being unwilling to subject himself to what he considered to be biased courts and unfairly administered laws,{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=152}} starting [[Caesar's civil war]]. |

|||

Whether the period starting with Caesar's civil war should really be called a portion of the republic is a matter of scholarly debate.{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=16}} After Caesar's victory, he ruled a dictatorial regime until his assassination in 44 BC at the hands of the [[Liberatores]].{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=33}} The Caesarian faction quickly gained control of the state,{{sfn|Flower|2010|p=33}} inaugurated the [[Second Triumvirate]] (comprising Caesar's adopted son [[Augustus|Octavian]] and the dictator's two most important supporters, [[Mark Antony]] and [[Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (triumvir)|Marcus Aemilius Lepidus]]), purged their political enemies, and successfully defeated the assassins in the [[Liberators' civil war]] at the [[Battle of Philippi]]. The second triumvirate failed to reach any mutually agreeable resolution; leading to the [[War of Actium|final civil war]] of the republic,{{sfn|Lintott|1999|p=213}} a war which the promagistrate governors and their troops won, and in doing so, permanently collapsed the republic. Octavian, now Augustus, became the first [[Roman Emperor]] and transformed the [[oligarchy|oligarchic]] republic into the [[autocracy|autocratic]] [[Roman Empire]]. |

|||

Pompey's career seems to have been driven by desire for military glory and disregard for traditional political constraints.{{sfn|Holland|2003|pp=141–2}} Pompey served next to Crassus and Julius Caesar as part of the first triumvirate of Rome, however, before this, the Roman aristocracy turned him down— as they were beginning to fear the young, popular and successful general. Pompey refused to disband his legions until his request was granted.<ref>Plutarch, ''[https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Pompey*.html Parallel Lives, Life of Pompey]'', p. 158 (Loeb Classical Library, 1917).</ref> The senate acceded, reluctantly granted him the title of proconsul and powers equal to those of Metellus, and sent him to Hispania.<ref>Boak, Arthur E.R. ''A History of Rome to 565 A.D.'', p. 152 (MacMillan, New York, 1922).</ref> |

|||

Pompey infamously wiped out what remained of Spartacus' troops in 71 BC, who had been pinned down by [[Marcus Crassus|Crassus]].<ref>Losch, p. 349; Fields, pp. 71–81.</ref> He received Rome's highest honor, the ''[[Roman triumph|triumph]]'', while Crassus the lesser honor of an ''[[ovation]]'', which hurt Crassus' pride.<ref>Fields, pp. 81–82; Losch, p. 349; Strauss, pp. 195–200.</ref> |

|||

In 69 BC, he conquered [[Syria]], defeated King [[Tigranes the Great|Tigranes]] of [[Armenia]], and replaced one [[puppet king]], [[Seleucus VII]] Philometor with his brother [[Antiochus XIII]] Asiaticus.<ref name=Pompey/> Four years later, he deposed the monarchy, replacing it with a governor.<ref name=Pompey/> This not only finished off the [[Seleucids]],<ref>Losch, pp. 379–390, 575.</ref> but brought in thousands of slaves and strange peoples, including the [[Judean]]s, to Rome, thus creating the [[Jewish diaspora]].<ref name=Strange>Losch, p. 349.</ref> |

|||

While many of Pompey's reckless actions ultimately increased discord in Rome, his unlucky alliance with Crassus and Caesar is cited as being especially dangerous to the Republic.<ref name=Syme /> In January 49 B.C., Caesar led his legions across the [[Rubicon River]] from [[Cisalpine Gaul]] to Italy, thus declaring war against Pompey and his forces. In August 48 B.C., with Pompey in pursuit, Caesar paused near Pharsalus, setting up camp at a strategic location.<ref name=":0">{{Cite news|url=http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/pompey-the-great-assassinated|title=Pompey the Great assassinated - Sep 28, 48 B.C. - HISTORY.com|work=HISTORY.com|access-date=2017-11-04}}</ref> When Pompey's senatorial forces fell upon Caesar's smaller army, they were entirely routed, and Pompey fled to Egypt. Pompey hoped that [[Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator|King Ptolemy]], his former client, would assist him, but the Egyptian king feared offending the victorious Caesar. On 28 September, Pompey was invited to leave his ships and come ashore at Pelusium. As he prepared to step onto Egyptian soil, he was treacherously struck down and killed by an officer of Ptolemy.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

===Second Triumvirate=== |

|||

{{Expand section|date=July 2022}} |

|||

{{See also|Second Triumvirate}} |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 130: | Line 115: | ||

* [[Democratic backsliding]] |

* [[Democratic backsliding]] |

||

* [[Fall of the Western Roman Empire]] |

* [[Fall of the Western Roman Empire]] |

||

* ''[[The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire]]'' by [[Edward Gibbon]] |

|||

== Notes == |

|||

{{notelist|30em}} |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 137: | Line 124: | ||

==Sources and further reading== |

==Sources and further reading== |

||

{{refbegin|30em}} |

{{refbegin|30em}} |

||

* {{ |

* {{cite book |last1=Abbott |first1=Frank Frost |title=A History and Descriptions of Roman Political Institutions |date=1963 |publisher=Noble Offset Printers Inc |location=New York |edition=3rd |orig-year=1901}} |

||

* {{ |

* {{cite book |last1=Börm |first1=Henning |last2=Gotter |first2=Ulrich |last3=Havener |first3=Wolfgang |title=A cultureofCivil War? "Bellum civile" and political communication in Late Republican Rome |date=2023 |publisher=Franz Steiner Verlag |location=Stuttgart |isbn=9783515134019}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last= |

* {{Cite book |last=Brunt |first=P.A. |title=The fall of the Roman Republic and related essays |date=1988 |publisher=Clarendon Press |isbn=0-19-814849-6|location=Oxford |oclc=16466585}} |

||

* {{ |

* {{cite book |last1=Duncan |first1=Mike |title=The storm before the storm: the beginning of the endofthe Roman republic |date=24 October 2017 |publisher=Hachette |location=New York |isbn=978-1-61039-721-6 |edition=1st}}<!-- Find better *academic* source. --> |

||

* {{Cite book|last= |

* {{Cite book |last=Dupont |first=Florence |title=Daily life in ancient Rome |date=1993 |publisher=Blackwell |isbn=0-631-17877-5|location=Oxford, UK |oclc=25788455 |translator-last=Woodall |translator-first=Christopher}} |

||

* {{Cite book | |

* {{Cite book |last1=Eisenstadt |first1=S. N. |last2=Roniger |first2=Luis |title=Patrons, clients, and friends : interpersonal relations and the structure of trust in society |date=1984 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=0-521-24687-3 |location=Cambridge |oclc=10299353}} |

||

* {{Cite book |last=Fields |first=Nic |title=Spartacus and the Slave War 73–71 BC : a gladiator rebels against Rome |date=2009 |publisher=Osprey |others=Steve Noon |isbn=978-1-84603-353-7 |location=Oxford |oclc=320495559}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |editor-last=Flower |editor-first=Harriet I. |title=The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic |year=2014 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-107-66942-0 |orig-year=2004 |edition=2nd}} |

|||

** {{harvc |last=Brennan |first=T Corey |c=Power and Process under the Republican "Constitution" |pages=19–53 |year=2014 |in=Flower}} |

** {{harvc |last=Brennan |first=T Corey |c=Power and Process under the Republican "Constitution" |pages=19–53 |year=2014 |in=Flower}} |

||

** {{harvc |last=von Ungern-Sternberg |first=Jorgen |c=The Crisis of the Roman Republic |pages=78–100 |year=2014 |in=Flower}} |

** {{harvc |last=von Ungern-Sternberg |first=Jorgen |c=The Crisis of the Roman Republic |pages=78–100 |year=2014 |in=Flower}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Flower|first=Harriet I.|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/301798480|title=Roman republics|date=2010|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-0-691-14043-8|location=Princeton|oclc=301798480}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last= |

* {{Cite book |last=Flower |first=Harriet I. |title=Roman republics |date=2010 |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0-691-14043-8|location=Princeton |oclc=301798480}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last= |

* {{Cite book |last=Gruen |first=Erich S. |title=The Last Generation of the Roman Republic |date=1995 |isbn=0-520-02238-6|location=Berkeley |oclc=943848}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last= |

* {{Cite book |last=Holland |first=Tom |title=Rubicon : the last years of the Roman Republic |date=2003 |publisher=Doubleday |isbn=0-385-50313-X |edition=1st |location=New York |oclc=52878507}}<!-- Find better *academic* source. --> |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Lintott |first1=Andrew |title=The Constitution of the Roman Republic |date=1999 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford |isbn=0-19-926108-3}} Reprinted 2003, 2009. |

|||

| ⚫ |

* {{Cite book|last=Meier|first=Christian |

||

* {{Cite book|last= |

* {{Cite book |last=Losch |first=Richard R. |title=All the people in the Bible : an a–z guide to the saints, scoundrels, and other characters in scripture |date=2008 |publisher=William B. Eerdmans |isbn=978-0-8028-2454-7|location=Grand Rapids |oclc=213599663}} |

||

| ⚫ | * {{Cite book |last=Meier |first=Christian |title=Caesar: a biography |date=1995 |publisher=BasicBooks/HarperCollins |others=David McLintock |isbn=0-465-00894-1 |location=New York |oclc=33246109}} |

||

| ⚫ | * {{cite book|author=Polybius|year=1823|title=The General History of Polybius: Translated from the Greek|publisher=Oxford: Printed by W. Baxter|edition=Fifth|volume=2}}<!-- consider replacement with chicago penelope version sourced from Loeb --> |

||

* {{Cite book|url=https:// |

* {{Cite book |last=Meier |first=Christian |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UPXvAAAAMAAJ |title=Res publica amissa: eine Studie zu Verfassung und Geschichte der späten römischen Republik |publisher=Suhrkamp |isbn=978-3-518-57506-2 |language=de|year=1997}} |

||

| ⚫ | * {{cite book |author=Polybius |year=1823 |title=The General History of Polybius: Translated from the Greek |publisher=Oxford: Printed by W. Baxter |edition=Fifth |volume=2}}<!-- consider replacement with chicago penelope version sourced from Loeb --> |

||

* {{cite book|author=Barbette Spaeth|title=The Roman Goddess Ceres|publisher=U. of Texas Press|year= 1996|isbn= 0-292-77693-4|author-link=Barbette Spaeth}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Ridley |first1=R. T. |title=The Fall of the Roman Republic |journal=Agora |date=2016 |volume=51 |issue=1 |page=66}} |

|||

| ⚫ |

* {{Cite book|last=Strauss|first=Barry S. |

||

* {{Cite book|last= |

* {{Cite book |editor-last=Seager |editor-first=Robin |title=The crisis of the Roman republic : studies in political and social history |date=1969 |publisher=Heffer |isbn=0-85270-024-5|location=Cambridge |oclc=28921}} |

||

* {{ |

* {{cite book |last=Spaeth |first=Barbette |title=The Roman Goddess Ceres |publisher=U. of Texas Press |year= 1996 |isbn= 0-292-77693-4|author-link=Barbette Spaeth}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Steel |first1=Catherine |title=The Roman Senate and the post-Sullan res publica |journal=Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte |date=2014 |volume=63 |issue=3 |page=328}} |

|||

| ⚫ | * {{Cite book |last=Strauss |first=Barry S. |title=The Spartacus war |date=2009 |publisher=Simon & Schuster |isbn=978-1-4165-3205-7 |edition=1st |location=New York |oclc=232979141}} |

||

* {{Cite book |last=Syme |first=Ronald |title=The provincial at Rome: and, Rome and the Balkans 80 BC – AD 14 |date=1999 |publisher=University of Exeter Press |others=Anthony Birley |isbn=0-85989-632-3 |oclc=59407034 |orig-date=1939}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Wiedemann |first=Thomas E. J. |title=Cicero and the end of the Roman Republic |year=1994 |publisher=Bristol Classical Press |isbn=1-85399-193-7 |location=London |oclc=31494651}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Wiseman |first=T. P. |title=Remembering the Roman people : essays on late-Republican politics and literature |date=2009 |publisher=Oxford Univ. Press |isbn=978-0-19-156750-6 |location=Oxford |oclc=328101074}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

{{refend}} |

||

| Line 165: | Line 160: | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Crisis of the Roman Republic}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Crisis of the Roman Republic}} |

||

[[Category:Crisis of the Roman Republic| ]] |

|||

[[Category:Foreign relations of ancient Rome]] |

[[Category:Foreign relations of ancient Rome]] |

||

[[Category:History of the Roman Republic]] |

[[Category:History of the Roman Republic]] |

||

| Line 172: | Line 168: | ||

[[Category:2nd century BC in the Roman Republic]] |

[[Category:2nd century BC in the Roman Republic]] |

||

[[Category:1st century BC in the Roman Republic]] |

[[Category:1st century BC in the Roman Republic]] |

||

[[Category:Civil disorder]] |

|||

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Substantial content is of dubious value (see talk related to slavery); fails to cover historiographical disputes. Please help improve this article if you can. (April 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

|

|---|

| Periods |

AD 284–641

AD 395–1453 |

| Constitution |

|

|

| Political institutions |

|

|

| Assemblies |

|

|

| Ordinary magistrates |

|

|

| Extraordinary magistrates |

|

|

| Public law |

|

|

| Titles and honours |

|

|

|

|

The crisis of the Roman Republic was an extended period of political instability and social unrest from about c. 133 BC to 44 BC that culminated in the demise of the Roman Republic and the advent of the Roman Empire.

The causes and attributes of the crisis changed throughout the decades, including the forms of slavery, brigandage, wars internal and external, overwhelming corruption, land reform, the invention of excruciating new punishments,[1] the expansion of Roman citizenship, and even the changing composition of the Roman army.[2]

Modern scholars also disagree about the nature of the crisis. Traditionally, the expansion of citizenship (with all its rights, privileges, and duties) was looked upon negatively by the contemporary Sallust, the modern Gibbon, and others of their respective schools, both ancient and modern, because it caused internal dissension, disputes with Rome's Italian allies, slave revolts, and riots.[3] However, other scholars have argued that as the Republic was meant to be res publica – the essential thing of the people – the poor and disenfranchised cannot be blamed for trying to redress their legitimate and legal grievances.[3]

More recently, beyond arguments about when the crisis of the Republic began (see below), there also have been arguments on whether there even was a crisis or multiple ones. Harriet Flower, in 2010, proposed a different paradigm encompassing multiple "republics" for the general whole of the traditional republican period with attempts at reform rather than a single "crisis" occurring over a period of eighty years.[4] Instead of a single crisis of the late Republic, Flower proposes a series of crises and transitional periods (excerpted only to the chronological periods after 139 BC):

| Years BC | Description |

|---|---|

| 139–88 | Republic 5: Third republic of the nobiles |

| 88–81 | Transitional period starting with Sulla's first coup and ending with his dictatorship |

| 81–60 | Republic 6: Sulla's republic (modified during Pompey and Crassus' consulship in 70) |

| 59–53 | First Triumvirate |

| 52–49 | Transitional period (Caesar's Civil War) |

| 49–44 | Caesar's dictatorship, with short transitional period after his death |

| 43–33 | Second Triumvirate |

Each different republic had different circumstances and while overarching themes can be traced,[5] "there was no single, long republic that carried the seeds of its own destruction in its aggressive tendency to expand and in the unbridled ambitions of its leading politicians".[6] The implications of this view put the fall of the republic in a context based around the collapse of the republican political culture of the nobiles and emphasis on Sulla's civil war followed by the fall of Sulla's republic in Caesar's civil war.[7]

For centuries, historians have argued about the start, specific crises involved, and end date for the crisis of the Roman Republic. As a culture (or "web of institutions"), Florence Dupont and Christopher Woodall wrote, "no distinction is made between different periods."[8] However, referencing Livy's opinion in his History of Rome, they assert that Romans lost liberty through their own conquests' "morally undermining consequences."[9]

Von Ungern-Sternberg argues for an exact start date of 10 December 134 BC, with the inauguration of Tiberius Gracchusastribune,[10] or alternately, when he first issued his proposal for land reform in 133 BC.[11] Appian of Alexandria wrote that this political crisis was "the preface to ... the Roman civil wars".[12] Velleius commented that it was Gracchus' unprecedented standing for re-election as tribune in 133 BC, and the riots and controversy it engendered, which started the crisis:

This was the beginning of civil bloodshed and of the free reign [sic] of swords in the city of Rome. From then on justice was overthrown by force and the strongest was preeminent.

— Velleius, Vell. Pat. 2.3.3–4, translated and cited by Harriet I. Flower[13]

In any case, the assassination of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC marked "a turning point in Roman history and the beginning of the crisis of the Roman Republic."[14]

Barbette S. Spaeth specifically refers to "the Gracchan crisis at the beginning of the Late Roman Republic ...".[15]

Nic Fields, in his popular history of Spartacus, argues for a start date of 135 BC with the beginning of the First Servile WarinSicily.[16] Fields asserts:

The rebellion of the slaves in Italy under Spartacus may have been the best organized, but it was not the first of its kind. There had been other rebellions of slaves that afflicted Rome, and we may assume that Spartacus was wise enough to profit by their mistakes.[17]

The start of the Social War (91–87 BC), when Rome's nearby Italian allies rebelled against her rule, may be thought of as the beginning of the end of the Republic.[18][19] Fields also suggests that things got much worse with the Samnite engagement at the Battle of the Colline Gate in 82 BC, the climax of the war between Sulla and the supporters of Gaius Marius.[20]

Barry Strauss argues that the crisis really started with "The Spartacus War" in 73 BC, adding that, because the dangers were unappreciated, "Rome faced the crisis with mediocrities".[21]

Pollio and Ronald Syme date the Crisis only from the time of Julius Caesar in 60 BC.[22][verification needed] Caesar's crossing of the Rubicon, a river marking the northern boundary of Roman Italy, with his army in 49 BC, a flagrant violation of Roman law, has become the clichéd point of no return for the Republic, as noted in many books, including Tom Holland's Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic.

The end of the Crisis can likewise either be dated from the assassination of Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC, after he and Sulla had done so much "to dismantle the government of the Republic",[23] or alternately when Octavian was granted the title of Augustus by the Senate in 27 BC, marking the beginning of the Roman Empire.[24] The end could also be dated earlier, to the time of the constitutional reforms of Julius Caesar in 49 BC.[citation needed]

After the Second Punic War, there was a great increase in income inequality. While the landed peasantry[27] was drafted to serve in increasingly long campaigns, their farms and homesteads fell into bankruptcy.[28] With Rome's great military victories, vast numbers of slaves were imported into Italy.[28] Significant mineral wealth was distributed unevenly to the population; the city of Rome itself expanded considerably in opulence and size; the freeing of slaves brought to Italy by conquest too would massively expand the number of urban and rural poor.[29] The republic, for reasons unclear to modern historians, in 177 BC also stopped regularly establishing Roman colonies in Italy; one of the major functions of these colonies was to land the urban and rural poor, increasing the draft pool of landed farmers as well as providing economic opportunities to the lower classes.[30]

The tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC led to a breakup of the long-standing norms of the republican constitution.[31] Gracchus was successful in passing legislation to pursue land reform,[32] but only over a norms-breaking attempt by Marcus Octavius—a tribune in the same year as Gracchus—to veto proceedings overwhelmingly supported by the people.[33] Gracchus' legislation would challenge the socio-political power of the old aristocracy,[31] along with eroding their economic interests.[a] The initial extra-constitutional actions by Octavius caused Gracchus to take similarly novel norms-breaking actions, that would lead even greater breakdowns in republican norms.[34] The backlash against Tiberius Gracchus' attempt to secure for himself a second term as tribune of the plebs would lead to his assassination by the then-pontifex maximus Scipio Nasica, acting in his role as a private citizen and against the advice of the consul and jurist Publius Mucius Scaevola.[35]

The Senate's violent reaction also served to legitimise the use of violence for political ends.[25] Political violence showed fundamentally that the traditional republican norms that had produced the stability of the middle republic were incapable of resolving conflicts between political actors. As well as inciting revenge killing for previous killings,[b] the repeated episodes also showed the inability of the existing political system to solve pressing matters of the day.[35] The political violence also further divided citizens with different political views and set a precedent that senators—even those without lawful executive authority—could use force to silence citizens merely for holding certain political beliefs.[36]

Tiberius Gracchus' younger brother Gaius Gracchus, who later was to win repeated office to the tribunate so to pass similarly expansive reforms, would be killed by similar violence. Consul Lucius Opimius was empowered by the senate to use military force (including a number of foreign mercenaries from Crete) in a state of emergency declared so to kill Gaius Gracchus, Marcus Fulvius Flaccus and followers. While the citizens killed in the political violence were not declared enemies, it showed clearly that the aristocracy believed violence was a "logical and more effective alternative to political engagement, negotiation, and compromise within the parameters set by existing norms".[37]

Further political violence emerged in the sixth consulship of Gaius Marius, a famous general, known to us as 100 BC. Marius had been consul consecutively for some years by this point, owing to the immediacy of the Cimbrian War.[38] These consecutive consulships violated Roman law, which mandated a decade between consulships, further weakening the primarily norms-based constitution. Returning to 100 BC, large numbers of armed gangs—perhaps better described as militias—engaged in street violence.[39] A candidate for high office, Gaius Memmius, was also assassinated.[39] Marius was called upon as consul to suppress the violence, which he did, with significant effort and military force.[c] His landless legionaries also affected voting directly, as while they could not vote themselves for failing to meet property qualifications, they could intimidate those who could.[39]

Following the Social War—which had the character of a civil war between Rome's Italian allies and loyalists—which was only resolved by Rome granting citizenship to almost all Italian communities, the main question looming before the state was how the Italians could be integrated into the Roman political system.[41] Tribune Publius Sulpicius Rufus in 88 BC attempted to pass legislation granting greater political rights to the Italians; one of the additions to this legislative programme included a transfer of command of the coming First Mithridatic War from SullatoGaius Marius, who had re-entered politics. Flower writes, "by agreeing to promote the career of Marius, Sulpicius ... decided to throw republican norms aside in his bid to control the political scene in Rome and get his reforms" passed.[41]

The attempts to recall Sulla led to his then-unprecedented and utterly unanticipated[42] marching on Rome with his army encamped at Nola (near Naples). This choice collapsed any republican norms about the use of force.[43] In this first (he would invade again) march on Rome, he declared a number of his political opponents enemies of the state and ordered their murder.[43] Marius would escape to his friendly legionary colonies in Africa. Sulpicius was killed.[43] He also installed two new consuls and forced major reforms of the constitution at sword-point,[38] before leaving on campaign against Mithridates.[44]

While Sulla was fighting Mithridates, Lucius Cornelius Cinna dominated domestic Roman politics, controlling elections and other parts of civil life. Cinna and his partisans were no friends of Sulla: they razed Sulla's house in Rome, revoked his command in name, and forced his family to flee the city.[45] Cinna himself would win election to the consulship three times consecutively; he also conducted a purge of his political opponents, displaying their heads on the rostra in the forum.[46] During the war, Rome fielded two armies against Mithridates: one under Sulla and another, fighting both Sulla and Mithridates.[45] Sulla returned in 82 BC at the head of his army, after concluding a generous peace with Mithridates, to retake the city from the domination of the Cinnan faction.[45] After winning a civil war and purging the republic of thousands of political opponents and "enemies" (many of whom were targeted for their wealth), he forced the Assemblies to make him dictator for the settling of the constitution,[47][48] with an indefinite term. Sulla also created legal barriers, which would only be lifted during the dictatorship of Julius Caesar some forty years later, against political participation by the relatives of those whom he ordered murdered.[42] And with this use of unprecedented violence at a new level, Sulla was able not only to take control of the state, but also retain control, unlike Scipio Nasica or Gaius Marius, both of whom quickly lost their influence after deploying force.[49]

Sulla's dictatorship ended the middle republic's culture of consensus-based senatorial decision-making [49] by purging many of those men who lived by and reproduced that culture. Generally, Sulla's dictatorial reforms attempted to concentrate political power into the Senate and the aristocratic assemblies, whilst trying to reduce the obstructive and legislative powers of the tribune and plebeian council.[50] To this end, he required that all bills presented to the Assemblies first be approved by the Senate, restricted the tribunician veto to only matters of individual requests for clemency, and required that men elected tribune would be barred from all other magistracies.[47][51] Beyond stripping the tribunate of its powers, the last provision was intended to prevent ambitious youth from seeking the office, by making it a dead end.[47]

Sulla also permanently enlarged the senate by promoting a large number of equestrians from the Italian countryside as well as automatically inducting the now-20 quaestors elected each year into the senate.[52] The senatorial class was so enlarged to staff newly-created permanent courts.[52][d] These reforms were an attempt to formalise and strengthen the legal system so prevent political players from emerging with too much power, as well as to make them accountable to the enlarged senatorial class.[53]

He also rigidly formalised the cursus honorum by clearly stating the progression of office and associated age requirements.[47] Next, to aid administration, he doubled the number of quaestors to 20 and added two more praetors; the greater number of magistrates also meant he could shorten the length of provincial assignments (and lessen the chances of building provincial power bases) by increasing the rate of turnover.[47] Moreover, magistrates were barred from seeking reelection to any post for ten years and barred for two years from holding any other post after their term ended.[47]

After securing election as consul in 80 BC, Sulla resigned the dictatorship and attempted to solidify his republican constitutional reforms.[47] Sulla's reforms proved unworkable.[54] The first years of Sulla's new republic were faced not only the continuation of the civil war against Quintus Sertorius in Spain, but also a revolt in 78 BC by the then-consul Marcus Aemilius Lepidus.[55] With significant popular unrest, the tribunate's powers were quickly restored by 70 BC by Sulla's own lieutenants': Pompey and Crassus.[56] Sulla passed legislation to make it illegal to march on Rome as he had,[57] but having just shown that doing so would bring no personal harm so long as one was victorious, this obviously had little effect.[56] Sulla's actions and civil war fundamentally weakened the authority of the constitution and created a clear precedent that an ambitious general could make an end-run around the entire republican constitution simply by force of arms.[47] The stronger law courts created by Sulla, along with reforms to provincial administration that forced consuls to stay in the city for the duration of their terms (rather than running to their provincial commands upon election), also weakened the republic:[58] the stringent punishments of the courts helped to destabilise,[59] as commanders would rather start civil wars than subject themselves to them, and the presence of both consuls in the city increased chances of deadlock.[60] Many Romans also followed Sulla's example and turned down provincial commands, concentrating military experience and glory into an even smaller circle of leading generals.[58]

Over the course of the late republic, formerly authoritative institutions lost their credibility and authority.[61] For example, the Sullan reforms to the Senate strongly split the aristocratic class between those who stayed in the city and those who rose to high office abroad, further increasing class divides between Romans, even at the highest levels.[62][58] Furthermore, the dominance of the military in the late republic, along with stronger ties between a general and his troops, caused by their longer terms of service together and the troops' reliance on that general to provide for their retirements,[25] along with an obstructionist central government,[60] made a huge number of malcontent soldiers willing to take up arms against the state. Adding in the institutionalisation of violence as a means to obstruct or force political change (eg the deaths of the Gracchi and Sulla's dictatorship, respectively),[25] the republic was caught in an ever more violent and anarchic struggle between the Senate, assemblies at Rome, and the promagistrates.

Even by the early-60s BC, political violence began to reassert itself, with unrest at the consular elections noted at every year between 66 and 63.[59] The revolt of Catiline—which we hear much about from the consul for that year, Cicero—was put down by violating the due process rights of citizens and introducing the death penalty to the Roman government's relationship with its citizens.[63] The anarchy of republican politics since the Sullan reforms had done nothing to address agrarian reform, the civic disabilities of proscribed families, or intense factionalism between Marian and Sullan supporters.[63] Through this whole period, Pompey's extraordinary multi-year commands in the east made him wealthy and powerful; his return in 62 BC could not be handled within the context of a republican system: his achievements were not recognised but nor could he be dispatched away from the city to win more victories.[64] His extraordinary position created a "volatile situation that the senate and the magistrates at home could not control".[64] Both Cicero's actions during his consulship and Pompey's great military successes challenged the republic's legal codes that were meant to restrain ambition and defer punishments to the courts.[63]

The domination of the state by the three-man group of the First Triumvirate—Caesar, Crassus, and Pompey—from 59 BC did little to restore order or peace in Rome.[65] The first "triumvirate" dominated republican politics by controlling elections, continually holding office, and violating the law through their long periods of ex officio political immunity.[66] This political authority so dominated other magistrates that they were unwilling to oppose their policies or voice opposition.[67] Political violence both became more acute and chaotic: the total anarchy that emerged in the mid-50s by duelling street gangs under the control of Publius Clodius Pulcher and Titus Annius Milo prevented orderly consular elections repeatedly in the 50s.[68] The destruction of the senate house and escalation of violence continued[69] until Pompey was simply appointed by the senate, without consultation of the assemblies, as sole consul in 52 BC.[68][70] The domination of the city by Pompey[71] and repeated political irregularities[72] led to Caesar being unwilling to subject himself to what he considered to be biased courts and unfairly administered laws,[73] starting Caesar's civil war.

Whether the period starting with Caesar's civil war should really be called a portion of the republic is a matter of scholarly debate.[74] After Caesar's victory, he ruled a dictatorial regime until his assassination in 44 BC at the hands of the Liberatores.[5] The Caesarian faction quickly gained control of the state,[5] inaugurated the Second Triumvirate (comprising Caesar's adopted son Octavian and the dictator's two most important supporters, Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus), purged their political enemies, and successfully defeated the assassins in the Liberators' civil war at the Battle of Philippi. The second triumvirate failed to reach any mutually agreeable resolution; leading to the final civil war of the republic,[61] a war which the promagistrate governors and their troops won, and in doing so, permanently collapsed the republic. Octavian, now Augustus, became the first Roman Emperor and transformed the oligarchic republic into the autocratic Roman Empire.

[Pollio] made his history of the Civil Wars begin not with the crossing of the Rubicon, but with the compact between Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)