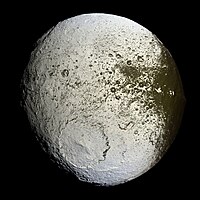

Natural color photomosaic combining Cassini images taken on 31 December 2004. It shows the dark Cassini Regio and its border with the bright Roncevaux Terra, several large craters (Falsaron above center, Turgis, the largest, at right), and the equatorial ridge (the Toledo and Tortelosa Montes).

| |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | G. D. Cassini |

| Discovery date | October 25, 1671 |

| Designations | |

| Saturn VIII | |

| Adjectives | Iapetian, Japetian |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| 3560820 km | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0286125 [1] |

| 79.3215 d | |

Average orbital speed | 3.26 km/s |

| Inclination |

|

| Satellite of | Saturn |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 1,492.0 × 1,492.0 × 1,424 km [3] |

| 734.5±2.8 km [3] | |

| 6700000 km2 | |

| Mass | (1.805635±0.000375)×1021 kg [4] |

Mean density | 1.088±0.013 g/cm³ [3] |

| 0.223 m/s2 | |

| 0.573 km/s | |

| 79.3215 d (synchronous) | |

| zero | |

| Albedo | 0.05–0.5[5] |

| Temperature | 90–130 K |

| 10.2–11.9[6] | |

Iapetus (/aɪˈæpɪtəs/; Greek: Ιαπετός), or occasionally Japetus /ˈdʒæpɪtəs/,[7] is the third-largest natural satelliteofSaturn, eleventh-largest in the Solar System,[8] and the largest body in the Solar System known not to be in hydrostatic equilibrium.[9] Iapetus is best known for its dramatic "two-tone" coloration. Discoveries by the Cassini mission in 2007 revealed several other unusual features, such as a massive equatorial ridge running three-quarters of the way around the moon.

Iapetus was discovered by Giovanni Domenico Cassini, an Italian astronomer, in October 1671. He had discovered it on the western side of Saturn and tried viewing it on the eastern side some months later, but was unsuccessful. This was also the case the following year, when he was again able to observe it on the western side, but not the eastern side. Cassini finally observed Iapetus on the eastern side in 1705 with the help of an improved telescope, finding it two magnitudes dimmer on that side.[10][11]

Cassini correctly surmised that Iapetus has a bright hemisphere and a dark hemisphere, and that it is tidally locked, always keeping the same face towards Saturn. This means that the bright hemisphere is visible from Earth when Iapetus is on the western side of Saturn, and that the dark hemisphere is visible when Iapetus is on the eastern side. The dark hemisphere was later named Cassini Regio in his honour.

Iapetus is named after the Titan Iapetus from Greek mythology. The name was suggested by John Herschel (son of William Herschel, discoverer of Mimas and Enceladus) in his 1847 publication Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope,[7] in which he advocated naming the moons of Saturn after the Titans, brothers and sisters of the Titan Cronus (whom the Romans equated with their god Saturn).

When first discovered, Iapetus was among four Saturnian moons labelled the Sidera Lodoicea by their discoverer Giovanni Cassini after King Louis XIV (the other three were Tethys, Dione and Rhea). However, astronomers fell into the habit of referring to them using Roman numerals, with Iapetus being Saturn V. Once Mimas and Enceladus were discovered in 1789, the numbering scheme was extended and Iapetus became Saturn VII. And with the discovery of Hyperion in 1848, Iapetus became Saturn VIII, which it is still known by today (see naming of natural satellites).

Geological features on Iapetus are named after characters and places from the French epic poem The Song of Roland. Examples of names used include the craters Charlemagne and Baligant, and the northern bright region, Roncevaux Terra. The one exception is Cassini Regio, the dark region of Iapetus, named after the region's discoverer, Giovanni Cassini.

The orbit of Iapetus is somewhat unusual. Although it is Saturn's third-largest moon, it orbits much farther from Saturn than the next closest major moon, Titan. It has also the most inclined orbital plane of the regular satellites; only the irregular outer satellites like Phoebe have more inclined orbits. The cause of this is unknown.

Because of this distant, inclined orbit, Iapetus is the only large moon from which the rings of Saturn would be clearly visible; from the other inner moons, the rings would be edge-on and difficult to see. From Iapetus, Saturn would appear to be 1°56' in diameter (four times the size of the Moon viewed from Earth).[12]

The low density of Iapetus indicates that it is mostly composed of ice, with only a small (~20%) amount of rocky materials.[13]

Unlike most of the large moons, its overall shape is neither spherical nor ellipsoid, but has a bulging waistline and squashed poles;[14] also, its unique equatorial ridge (see below) is so high that it visibly distorts Iapetus's shape even when viewed from a distance. These features often lead it to be characterized as walnut-shaped.

Iapetus is heavily cratered, and Cassini images have revealed large impact basins, at least five of which are over 350 km wide. The largest, Turgis, has a diameter of 580 km;[15] its rim is extremely steep and includes a scarp about 15 km high.[16] Iapetus is known to support long-runout landslides or sturzstroms, possibly supported by ice sliding.[17]

In the 17th century, Giovanni Cassini observed that he could see Iapetus only on the west side of Saturn and never on the east. He correctly deduced that Iapetus is locked in synchronous rotation about Saturn and that one side of Iapetus is darker than the other, conclusions later confirmed by larger telescopes.

The difference in colouring between the two Iapetian hemispheres is striking. The leading hemisphere and sides are dark (albedo 0.03–0.05) with a slight reddish-brown coloring, while most of the trailing hemisphere and poles are bright (albedo 0.5–0.6, almost as bright as Europa). Thus, the apparent magnitude of the trailing hemisphere is around 10.2, whereas that of the leading hemisphere is around 11.9—beyond the capacity of the best telescopes in the 17th century. The pattern of coloration is analogous to a spherical yin-yang symbol or the two sections of a tennis ball. The dark region is named Cassini Regio, and the bright region is divided into Roncevaux Terra north of the equator, and Saragossa Terra south of it. Before optical observations could be made by deep space probes, theories about the reason for this dichotomy included an asteroid shearing off part of the moon's crust.[18] The original dark material is believed to have come from outside Iapetus, but now it consists principally of lag from the sublimation of ice from the warmer areas of Iapetus's surface.[19][20][21] It contains organic compounds similar to the substances found in primitive meteorites or on the surfaces of comets; Earth-based observations have shown it to be carbonaceous, and it probably includes cyano-compounds such as frozen hydrogen cyanide polymers.

On September 10, 2007 the Cassini orbiter passed within 1,227 kilometres (762 mi) of Iapetus and returned images showing that both hemispheres are heavily cratered.[22] The color dichotomy of scattered patches of light and dark material in the transition zone between Cassini Regio and the bright areas exists at very small scales, down to the imaging resolution of 30 meters. There is dark material filling in low-lying regions, and light material on the weakly illuminated pole-facing slopes of craters, but no shades of grey.[23] The dark material is a very thin layer, only a few tens of centimeters (approx. one foot) thick at least in some areas,[24] according to Cassini radar imaging and the fact that very small meteor impacts have punched through to the ice underneath.[21][25]

NASA scientists now believe that the dark material is lag (residue) from the sublimation (evaporation) of water ice on the surface of Iapetus,[20][25] possibly darkened further upon exposure to sunlight. Because of its slow rotation of 79 days (equal to its revolution and the longest in the Saturnian system), Iapetus would have had the warmest daytime surface temperature and coldest nighttime temperature in the Saturnian system even before the development of the color contrast; near the equator, heat absorption by the dark material results in a daytime temperatures of 129 K in the dark Cassini Regio compared to 113 K in the bright regions.[21][26] The difference in temperature means that ice preferentially sublimates from Cassini Regio, and deposits in the bright areas and especially at the even colder poles. Over geologic time scales, this would further darken Cassini Regio and brighten the rest of Iapetus, creating a positive feedback thermal runaway process of ever greater contrast in albedo, ending with all exposed ice being lost from Cassini Regio.[21] It is estimated that over a period of one billion years at current temperatures, dark areas of Iapetus would lose about 20 meters of ice to sublimation, while the bright regions would lose only 10 centimeters, not considering the ice transferred from the dark regions.[26][27] This model explains the distribution of light and dark areas, the absence of shades of grey, and the thinness of the dark material covering Cassini Regio. The redistribution of ice is facilitated by Iapetus's weak gravity, which means that at ambient temperatures a water molecule can migrate from one hemisphere to the other in just a few hops.[21]

However, a separate process of color segregation would be required to get the thermal feedback started. The initial dark material is thought to have been debris blasted by meteors off small outer moons in retrograde orbits and swept up by the leading hemisphere of Iapetus. The core of this model is some 30 years old, and was revived by the September 2007 flyby.[19][20]

Light debris outside of Iapetus's orbit, either knocked free from the surface of a moon by micrometeoroid impacts or created in a collision, would spiral in as its orbit decays. It would have been darkened by exposure to sunlight. A portion of any such material that crossed Iapetus's orbit would have been swept up by its leading hemisphere, coating it; once this process created a modest contrast in albedo, and so a contrast in temperature, the thermal feedback described above would have come into play and exaggerated the contrast.[20][21] In support of the hypothesis, simple numerical models of the exogenic deposition and thermal water redistribution processes can closely predict the two-toned appearance of Iapetus.[21] A subtle color dichotomy between Iapetus's leading and trailing hemispheres, with the former being more reddish, can in fact be observed in comparisons between both bright and dark areas of the two hemispheres.[20] In contrast to the elliptical shape of Cassini Regio, the color contrast closely follows the hemisphere boundaries; the gradation between the differently colored regions is gradual, on a scale of hundreds of km.[20] The next moon inward from Iapetus, chaotically rotating Hyperion, also has an unusual reddish color.

The largest reservoir of such infalling material is Phoebe, the largest of the outer moons. Although Phoebe's composition is closer to that of the bright hemisphere of Iapetus than the dark one,[28] dust from Phoebe would only be needed to establish a contrast in albedo, and presumably would have been largely obscured by later sublimation. The discovery of a tenuous disk of material in the plane of and just inside Phoebe's orbit was announced on 6 October 2009,[29] supporting the model.[30] The disk extends from 128 to 207 times the radius of Saturn, while Phoebe orbits at an average distance of 215 Saturn radii. It was detected with the Spitzer Space Telescope,

Current triaxial measurements of Iapetus give it dimensions of 746 × 746 × 712 km, with a mean radius of 734.5 ± 2.8 km.[3] However, these measurements may be inaccurate on the kilometer scale as Iapetus's entire surface has not yet been imaged in high enough resolution. The observed oblateness corresponds to a rotation period of 10 hours, not to the 79 days observed. A possible explanation for this is that the shape of Iapetus was frozen by formation of a thick crust shortly after its formation, while its rotation continued to slow afterwards due to tidal dissipation, until it became tidally locked.[14]

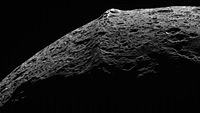

A further mystery of Iapetus is the equatorial ridge that runs along the center of Cassini Regio, about 1,300 km long, 20 km wide, and 13 km high. It was discovered when the Cassini spacecraft imaged Iapetus on December 31, 2004. Peaks in the ridge rise more than 20 km above the surrounding plains, making them some of the tallest mountains in the Solar System. The ridge forms a complex system including isolated peaks, segments of more than 200 km and sections with three near parallel ridges.[31] Within the bright regions there is no ridge, but there are a series of isolated 10 km peaks along the equator.[32] The ridge system is heavily cratered, indicating that it is ancient. The prominent equatorial bulge gives Iapetus a walnut-like appearance.

It is not clear how the ridge formed. One difficulty is to explain why it follows the equator almost perfectly. There are at least four current hypotheses, but none of them explains why the ridge is confined to Cassini Regio.

The moons of Saturn are typically thought to have formed through co-accretion, a similar process to that believed to have formed the planets in the Solar System. As the young gas giants formed, they were surrounded by discs of material that gradually coalesced into moons. However, a proposed model on the formation of Titan suggests that Titan was instead formed in a series of giant impacts between pre-existing moons. Iapetus and Rhea are thought to have formed from part of the debris of these collisions.[37] More-recent studies, however, suggest that all of Saturn's moons inward of Titan are no more than 100 million years old; thus, Iapetus is unlikely to have formed in the same series of collisions as Rhea and all the other moons inward of Titan, and—along with Titan—may be a primordial satellite.[38]

Iapetus has been imaged multiple times from moderate distances by the Cassini orbiter. However, its great distance from Saturn makes close observation difficult. Cassini made one targeted close flyby, at a minimum range of 1,227 kilometres (762 mi), on September 10, 2007.[22]

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

{{cite journal}}: Invalid |ref=harv (help)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

|

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Listed in approximately increasing distance from Saturn | |||||||

| Ring moonlets |

| ||||||

| Ring shepherds |

| ||||||

| Other inner moons |

| ||||||

| Alkyonides |

| ||||||

| Large moons (with trojans) |

| ||||||

| Inuit group (12) |

| ||||||

| Gallic group (7) |

| ||||||

| Norse group (100) |

| ||||||

| Outlier prograde irregular moons |

| ||||||

| |||||||

|

Natural satellites of the Solar System

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Planetary satellitesof |

| |

| Dwarf planet satellitesof |

| |

| Minor-planet moons |

| |

| Ranked by size |

| |

| ||

|

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Geography |

|

| Moons |

|

| Astronomy |

|

| Exploration |

|

| Related |

|

| |