|

mNo edit summary

|

m Reverted edits by 12.171.220.18 (talk) (HG) (3.4.12)

|

||

| (156 intermediate revisions by 98 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Prominent lunar impact crater}}{{use dmy dates|date=March 2023}} |

|||

{{About|the lunar crater|the Martian crater with the same eponym|Tycho Brahe (crater)}} |

|||

{{other uses2|Tycho}} |

|||

{{Infobox Lunar crater |

{{Infobox Lunar crater |

||

| |

| name = Tycho |

||

| image = Tycho LRO.png |

|||

|caption = Tycho seen by Lunar Orbiter 5. [[NASA]] |

|||

| |

| image_size = |

||

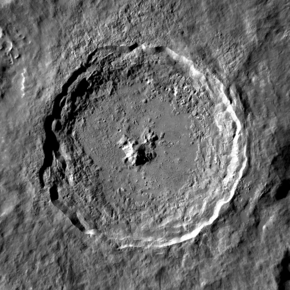

| caption = Tycho seen by [[Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter]] (rotate display if you see a [[crater illusion]] due to the atypical position of the light source). [[NASA]] |

|||

|N_or_S = S |

|||

| coordinates = {{coord|43.31|S|11.36|W|globe:moon_type:landmark|display=inline,title}} |

|||

|longitude = 11.36 |

|||

| diameter = 85 km (53.4 miles) |

|||

|E_or_W = W |

|||

| depth = {{convert|4.7|km|mi|abbr=on}}<ref name="Margot99">{{cite journal |last1=Margot |first1=Jean-Luc |last2=Campbell |first2=Donald B. |last3=Jurgens |first3=Raymond F. |last4=Slade |first4=Martin A. |title=The topography of Tycho Crater |journal=Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets |date=25 May 1999 |volume=104 |issue=E5 |pages=11875–11882 |doi=10.1029/1998JE900047|bibcode=1999JGR...10411875M }}</ref> |

|||

|diameter = 86.21 km |

|||

| |

| colong = 12 |

||

| |

| eponym = [[Tycho Brahe]] |

||

|eponym = [[Tycho Brahe]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

[[Image:Lage des Mondkraters Tycho.jpg|thumb|right|Location of Tycho as seen from the [[Northern Hemisphere]]]] |

|||

'''Tycho''' is a prominent [[Moon|lunar]] [[impact crater]] located in the southern lunar highlands, named after the Danish astronomer [[Tycho Brahe]] (1546-1601). To the south is the crater [[Street (crater)|Street]]; to the east is [[Pictet (crater)|Pictet]], and to the north-northeast is [[Sasserides (crater)|Sasserides]]. The surface around Tycho is replete with craters of various sizes, many overlapping still older craters. Some of the smaller craters are secondary craters formed from larger chunks of [[ejecta]] from Tycho. |

|||

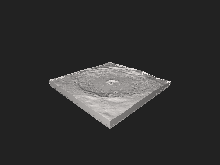

[[File:Tycho.stl|thumb|3D model of Tycho crater]] |

|||

'''Tycho''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|t|aɪ|k|oʊ}}) is a prominent [[Lunar craters|lunar impact]] [[impact crater|crater]] located in the southern lunar highlands, named after the Danish astronomer [[Tycho Brahe]] (1546–1601).<ref name=gpn>{{gpn|6163}}, accessed 19 February 2019</ref> It is estimated to be 108 million years old.<ref name="lro">{{cite web |title=The floor of Tycho crater |series=[[Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter]] |publisher=[[NASA]] |url=https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/LRO/multimedia/lroimages/lroc-20100114-tycho.html |date=3 August 2017 |access-date=1 July 2018 |archive-date=30 March 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170330203111/https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/LRO/multimedia/lroimages/lroc-20100114-tycho.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Lage des Mondkraters Tycho.jpg|thumb|right|Location of Tycho.]] |

|||

To the south of Tycho is the crater [[Street (crater)|Street]], to the east is [[Pictet (crater)|Pictet]], and to the north-northeast is [[Sasserides (crater)|Sasserides]]. The surface around Tycho is replete with craters of various sizes, many overlapping still older craters. Some of the smaller craters are secondary craters formed from larger chunks of [[ejecta]] from Tycho. |

|||

It is one of the [[Moon|Moon's]] brightest craters,<ref name=lro/> with a diameter of {{cvt|85|km}}<ref>{{cite news |last=Wood |first=Charles A. |date=2006-08-01 |title=Tycho: The metropolitan crater of the Moon |magazine=[[Sky & Telescope]] |url=http://www.skyandtelescope.com/observing/celestial-objects-to-watch/tycho-the-metropolitan-crater-of-the-moon/ |access-date=2018-06-19}}</ref> and a depth of {{cvt|4700|m}}.<ref name=Margot99></ref> |

|||

==Age and description== |

==Age and description== |

||

Tycho is a relatively young crater, with an estimated age of 108 |

Tycho is a relatively young crater, with an estimated age of 108 million years ([[Annum|Ma]]), based on analysis of samples of the crater ray recovered during the {{nobr|[[Apollo 17]]}} mission.<ref name=lro/> This age initially suggested that the impactor may have been a member of the [[Baptistina family]] of asteroids, but as the composition of the impactor is unknown this remained conjecture.<ref> |

||

{{cite news |

|||

| date=September 5, 2007 |

| date=September 5, 2007 |

||

| title=Breakup event in the main asteroid belt likely caused dinosaur extinction 65 million years ago |

| title=Breakup event in the main asteroid belt likely caused dinosaur extinction 65 million years ago |

||

| publisher=Physorg |

| publisher=[[Physorg]] |

||

| url=http://www.physorg.com/news108218928.html |

| url=http://www.physorg.com/news108218928.html |

||

| access-date=2007-09-06 |

|||

| accessdate=2007-09-06 }}</ref> which was previously believed to be responsible for the formation of [[Chicxulub Crater]] and the [[Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event|extinction of the dinosaurs]]. However, that possibility was ruled out by the [[Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer]] in 2011. |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

However, this possibility was ruled out by the [[Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer]] in 2011, as it was discovered that the Baptistina family was produced much later than expected, having formed approximately 80 million years ago.<ref>{{cite news |last=Plotner |first=Tammy |date=2015-12-24 |title=Did asteroid Baptistina kill the dinosaurs? Think other-WISE |website=[[Universe Today]] |url=https://www.universetoday.com/89050/did-asteroid-baptistina-kill-the-dinosaurs-think-other-wise/#more-89050}}</ref> |

|||

The crater is sharply defined, unlike older craters that have been degraded by subsequent impacts. The interior has a high [[albedo feature|albedo]] that is prominent when the Sun is overhead, and the crater is surrounded by a distinctive [[ray system]] forming long spokes that reach as long as 1,500 |

The crater is sharply defined, unlike older craters that have been degraded by subsequent impacts. The interior has a high [[albedo feature|albedo]] that is prominent when the Sun is overhead, and the crater is surrounded by a distinctive [[ray system]] forming long spokes that reach as long as 1,500 kilometers. Sections of these rays can be observed even when Tycho is illuminated only by [[planetshine|earthlight]]. Due to its prominent rays, Tycho is mapped as part of the [[Copernican period|Copernican System]].<ref>{{cite report |author1=McCauley, John F. |author2=Trask, Newell J. |year=1987 |title=The Geologic History of the Moon |editor-link=Donald Wilhelms |editor=Wilhelms, D.E. |publisher=[[United States Geological Survey]] |series=Professional Paper |volume=1348 |at=Plate 11: Copernican system |url=https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/pp1348 }}</ref> |

||

[[Image:Tycho Crater.jpg|thumb|left|250px|The large [[ray system]] centered on Tycho]] |

[[Image:Tycho Crater.jpg|thumb|left|250px|The large [[ray system]] centered on Tycho]] |

||

The ramparts beyond the rim have a lower albedo than the interior for a distance of over a hundred kilometers, and are free of the ray markings that lie beyond. This darker rim may have been formed from minerals excavated during the impact. |

The ramparts beyond the rim have a lower albedo than the interior for a distance of over a hundred kilometers, and are free of the ray markings that lie beyond. This darker rim may have been formed from minerals excavated during the impact. |

||

Its inner wall is slumped and [[Terrace ( |

Its inner wall is slumped and [[Terrace (geology)|terraced]], sloping down to a rough but nearly flat floor exhibiting small, knobby domes. The floor displays signs of past volcanism, most likely from rock melt caused by the impact. Detailed [[Astrophotography|photograph]]s of the floor show that it is covered in a criss-crossing array of cracks and small hills. The central peaks rise {{convert|1600|m|ft|sp=us}} above the floor, and a lesser peak stands just to the northeast of the primary [[massif]]. |

||

Infrared observations of the lunar surface during an eclipse have demonstrated that Tycho cools at a slower rate than other parts of the surface, making the crater a "hot spot". This effect is caused by the difference in materials that cover the crater. |

Infrared observations of the lunar surface during an eclipse have demonstrated that Tycho cools at a slower rate than other parts of the surface, making the crater a "hot spot". This effect is caused by the difference in materials that cover the crater. |

||

[[Image:Tycho Crater Panorama.jpg|thumb |

[[Image:Tycho Crater Panorama.jpg|thumb|Panoramic view of the lunar surface taken by {{nobr|[[Surveyor 7]],}} which landed about {{convert|29|km|mi|abbr=on}} from the rim of Tycho]] |

||

The rim of this crater was chosen as the target of the [[Surveyor 7]] mission. The robotic spacecraft safely touched down north of the crater in January 1968. The craft performed chemical measurements of the surface, finding a composition different from the maria. From this, one of the main components of the highlands was theorized to be [[anorthosite]], an [[aluminium]]-rich mineral. The crater was also imaged in great detail by [[Lunar Orbiter 5]]. |

|||

The rim of this crater was chosen as the target of the {{nobr|[[Surveyor 7]]}} mission. The robotic spacecraft safely touched down north of the crater in January 1968. The craft performed chemical measurements of the surface, finding a composition different from the maria. From this, one of the main components of the highlands was theorized to be [[anorthosite]], an [[aluminium]]-rich mineral. The crater was also imaged in great detail by {{nobr|[[Lunar Orbiter 5]].}} |

|||

From the 1950s through the 1990s, NASA aerodynamicist Dean Chapman and others advanced the lunar origin theory of [[tektite]]s. Chapman used complex orbital computer models and extensive wind tunnel tests to support the theory that the so-called Australasian tektites originated from the Rosse ejecta ray of Tycho. Until the Rosse ray is sampled, a lunar origin for these tektites cannot be ruled out. |

From the 1950s through the 1990s, NASA aerodynamicist Dean Chapman and others advanced the lunar origin theory of [[tektite]]s. Chapman used complex orbital computer models and extensive wind tunnel tests to support the theory that the so-called Australasian tektites originated from the Rosse ejecta ray of Tycho. Until the Rosse ray is sampled, a lunar origin for these tektites cannot be ruled out. |

||

This crater was drawn on lunar maps as early as 1645, when [[Antonius Maria Schyrleus de Rheita]] depicted the bright ray system. |

This crater was drawn on lunar maps as early as 1645, when [[Antonius Maria Schyrleus de Rheita|A.M.S. de Rheita]] depicted the bright ray system. |

||

== |

== Names == |

||

Tycho is named after the Danish astronomer [[Tycho Brahe]].<ref name=gpn/> Like many of the craters on the Moon's near side, it was given its name by the [[Society of Jesus|Jesuit]] astronomer [[Giovanni Battista Riccioli|G.B. Riccioli]], whose 1651 nomenclature system has become standardized.{{sfn|Whitaker|2003|pp=61}}<ref>[[:commons:File:Riccioli1651MoonMap.jpg|Riccioli map of the Moon (1651)]]</ref> Earlier lunar cartographers had given the feature different names. [[Pierre Gassendi]] named it Umbilicus Lunaris ('the [[navel]] of the Moon').{{sfn|Whitaker|2003|pp=33}} [[Michael van Langren|van Langren]]'s 1645 map calls it "Vladislai IV" after [[Władysław IV Vasa]], [[King of Poland]].{{sfn|Whitaker|2003|pp=198}}<ref>[[:commons:File:Langrenus map of the Moon 1645.jpg|Langren's map of the Moon (1645)]]</ref> And [[Johannes Hevelius]] named it 'Mons Sinai' after [[Mount Sinai]].<ref>[[:commons:File:Hevelius Map of the Moon 1647.jpg|Hevelius map of the Moon (1647)]]</ref> |

|||

By convention these features are identified on Lunar maps by placing the letter on the side of the crater midpoint that is closest to Tycho. |

|||

== Satellite craters == |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

!width="25%" style="background:#eeeeee;" |Tycho |

|||

By convention, these features are identified on lunar maps by placing the letter on the side of the crater midpoint that is closest to Tycho. |

|||

!width="25%" style="background:#eeeeee;" |Latitude |

|||

!width="25%" style="background:#eeeeee;" |Longitude |

|||

{| class="wikitable sortable" style="text-align:center" |

|||

!width="25%" style="background:#eeeeee;" |Diameter |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! Tycho |

|||

|align="center"|A |

|||

! class="unsortable" | Coordinates |

|||

|align="center"|39.9° S |

|||

! Diameter, km |

|||

|align="center"|12.0° W |

|||

|align="center"|31 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|A |

|||

|align="center"|B |

|||

|{{Coord|39.94|S|12.07|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho A}} |

|||

|align="center"|43.9° S |

|||

|29 |

|||

|align="center"|13.9° W |

|||

|align="center"|13 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|B |

|||

|align="center"|C |

|||

|{{Coord|43.99|S|13.92|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho B}} |

|||

|align="center"|44.3° S |

|||

|14 |

|||

|align="center"|13.7° W |

|||

|align="center"|7 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|C |

|||

|align="center"|D |

|||

|{{Coord|44.12|S|13.46|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho C}} |

|||

|align="center"|45.6° S |

|||

|7 |

|||

|align="center"|14.0° W |

|||

|align="center"|27 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|D |

|||

|align="center"|E |

|||

|{{Coord|45.58|S|14.07|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho D}} |

|||

|align="center"|42.2° S |

|||

|26 |

|||

|align="center"|13.5° W |

|||

|align="center"|14 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|E |

|||

|align="center"|F |

|||

|{{Coord|42.34|S|13.66|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho E}} |

|||

|align="center"|40.9° S |

|||

|13 |

|||

|align="center"|13.1° W |

|||

|align="center"|16 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|F |

|||

|align="center"|H |

|||

|{{Coord|40.91|S|13.21|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho F}} |

|||

|align="center"|45.2° S |

|||

|17 |

|||

|align="center"|15.8° W |

|||

|align="center"|8 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|H |

|||

|align="center"|J |

|||

|{{Coord|45.29|S|15.92|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho H}} |

|||

|align="center"|42.5° S |

|||

|8 |

|||

|align="center"|15.3° W |

|||

|align="center"|11 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|J |

|||

|align="center"|K |

|||

|{{Coord|42.58|S|15.42|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho J}} |

|||

|align="center"|45.1° S |

|||

|11 |

|||

|align="center"|14.3° W |

|||

|align="center"|6 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|K |

|||

|align="center"|P |

|||

|{{Coord|45.18|S|14.38|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho K}} |

|||

|align="center"|45.3° S |

|||

|6 |

|||

|align="center"|13.0° W |

|||

|align="center"|8 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|P |

|||

|align="center"|Q |

|||

|{{Coord|45.44|S|13.06|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho P}} |

|||

|align="center"|42.5° S |

|||

|7 |

|||

|align="center"|15.9° W |

|||

|align="center"|21 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|Q |

|||

|align="center"|R |

|||

|{{Coord|42.50|S|15.99|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho Q}} |

|||

|align="center"|41.8° S |

|||

|20 |

|||

|align="center"|13.6° W |

|||

|align="center"|5 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|R |

|||

|align="center"|S |

|||

|{{Coord|41.91|S|13.68|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho R}} |

|||

|align="center"|43.4° S |

|||

|4 |

|||

|align="center"|16.1° W |

|||

|align="center"|3 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|S |

|||

|align="center"|T |

|||

|{{Coord|43.47|S|16.30|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho S}} |

|||

|align="center"|41.2° S |

|||

|3 |

|||

|align="center"|12.5° W |

|||

|align="center"|14 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|T |

|||

|align="center"|U |

|||

|{{Coord|41.15|S|12.62|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho T}} |

|||

|align="center"|41.0° S |

|||

|14 |

|||

|align="center"|13.8° W |

|||

|align="center"|19 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|U |

|||

|align="center"|V |

|||

|{{Coord|41.08|S|13.91|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho U}} |

|||

|align="center"|41.7° S |

|||

|20 |

|||

|align="center"|15.3° W |

|||

|align="center"|4 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|V |

|||

|align="center"|W |

|||

|{{Coord|41.72|S|15.43|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho V}} |

|||

|align="center"|43.2° S |

|||

|4 |

|||

|align="center"|15.3° W |

|||

|align="center"|19 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|W |

|||

|align="center"|X |

|||

|{{Coord|43.30|S|15.38|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho W}} |

|||

|align="center"|43.8° S |

|||

|21 |

|||

|align="center"|15.2° W |

|||

|align="center"|13 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|X |

|||

|align="center"|Y |

|||

|{{Coord|43.84|S|15.25|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho X}} |

|||

|align="center"|44.1° S |

|||

|12 |

|||

|align="center"|15.8° W |

|||

|align="center"|19 km |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|Y |

|||

|align="center"|Z |

|||

|{{Coord|44.12|S|15.93|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho Y}} |

|||

|align="center"|43.1° S |

|||

|22 |

|||

|align="center"|16.2° W |

|||

|- |

|||

|align="center"|24 km |

|||

|Z |

|||

|{{Coord|43.23|S|16.35|W|globe:moon|name=Tycho Z}} |

|||

|23 |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

==Fictional references== |

== Fictional references == |

||

There is a chapter entitled "Tycho" in Jules Verne's [[Around the Moon]] ([[Autour de la Lune]], 1870) which describes the crater and its ray system. |

* There is a chapter entitled "Tycho" in Jules Verne's ''[[Around the Moon]]'' ([[Around the Moon|''Autour de la Lune'']], 1870) which describes the crater and its ray system. |

||

* In [[Robert A. Heinlein|R.A. Heinlein]]'s 1940 short story "[[Blowups Happen]]", a character speculates that Tycho may have been the location of a sentient race's main atomic power plant, in a past time when the Moon was still habitable—and that the plant exploded, causing the craters, the rays spreading from Tycho, and the death of all life on the Moon. |

|||

Tycho was the location of the [[Monolith_(Space Odyssey)#Tycho Magnetic Anomaly-1|Tycho Magnetic Anomaly]] (TMA-1), and subsequent excavation of an alien monolith, in [[2001: A Space Odyssey (novel)|''2001: A Space Odyssey'']], the seminal science-fiction film by [[Stanley Kubrick]] and book by [[Arthur C. Clarke]]. One of the [[Clavius Base]] scientists made the prophetic assessment that the monolith "appears to have been ''deliberately buried''." |

|||

* [[Clifford Simak|C.D. Simak]] set his 1961 novelette ''The Trouble with Tycho'', at the lunar crater. He also postulated that the crater's rays were composed of volcanic glass ([[tektites]]) akin to a theory postulated by NASA researchers Dean Chapman and John O'Keefe in the 1970s. |

|||

It also serves as the location of "Tycho City" in ''[[Star Trek: First Contact]]''; a lunar metropolis by the 24th century. |

|||

* In [[Robert A. Heinlein|Heinlein]]'s 1966 book ''[[The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress]]'', Tycho is the location of the lunar habitat named "Tycho Under". |

|||

In the film ''[[Can't Buy Me Love (film)|Can't Buy Me Love]]'', Cindy notices Tycho while looking through a telescope on her final "contractual" date with Ronny in the Airplane Graveyard. |

|||

* Tycho was the location of the [[Tycho Magnetic Anomaly]] (TMA-1), and subsequent excavation of an alien monolith, in [[2001: A Space Odyssey (novel)|''2001: A Space Odyssey'']], the seminal 1968 science-fiction film by [[Stanley Kubrick]] and book by [[Arthur C. Clarke]]. |

|||

In [[Robert A. Heinlein]]'s book ''[[The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress]]'', Tycho is the location of the lunar habitat "Tycho Under". |

|||

* In the 1987 film ''[[Can't Buy Me Love (film)|Can't Buy Me Love]]'', Cindy notices Tycho while looking through a telescope on her final "contractual" date with Ronny in the Airplane Graveyard. |

|||

In [[Jack Williamson]]'s novel ''[[Terraforming Earth]]'', the crater is utilized for "Tycho Base", a self sustaining, robot controlled installation aimed at restoring life to the (dead) planet Earth after an asteroid sterilizes the biosphere. |

|||

* It also serves as the location of "Tycho City" in the 1996 film ''[[Star Trek: First Contact]]''; a lunar metropolis by the 24th century. |

|||

In Heinlein's short story ''[[Blowups Happen]]'', a character hypothesizes that Tycho may have been the location of a sentient race's main atomic power plant, in a past time when the Moon was still habitable—and that the plant exploded, causing the craters, the rays spreading from Tycho, and the death of all life on the Moon. |

|||

* In [[Jack Williamson]]'s 2001 novel ''Terraforming Earth'', the crater is utilized for "Tycho Base", a self-sustaining, robot-controlled installation aimed at restoring life to the (dead) planet Earth after an asteroid sterilizes the biosphere. |

|||

[[Clifford Simak]] set a novelette ''[[The Trouble with Tycho]]'', at the lunar crater. He also postulated that the crater's rays were composed of volcanic glass ([[tektites]]) akin to a theory postulated by NASA researchers Dean Chapman and John O'Keefe in the 1970s. |

|||

* In the 2019 film [[Ad Astra (film)|''Ad Astra'']], the Moon base is situated in the Tycho crater. This is Roy's first stop on his journey to Mars. |

|||

Crater Tycho figures prominently in the [[Matthew Looney]] and [[Maria Looney]] series of children's books set on the Moon, authored by [[Jerome Beatty]]. |

|||

* Crater Tycho figures prominently in the [[Matthew Looney]] and [[Maria Looney]] series of children's books set on the Moon, authored by [[Jerome Beatty]]. |

|||

In the film ''[[Men in Black (film)|Men in Black]]'', the character [[agent K]], played by [[Tommy Lee Jones]], informs an alien bug that it is in violation of "section 4153 of the Tycho Treaty." |

|||

* In [[Roger Macbride Allen|R.M. Allen's]] ''Hunted Earth'' novels, the 'naked purples' own a former penal colony in or around Tycho crater known as "Tycho Purple Penal" (see ''[[The Ring of Charon]]''). |

|||

In the Retrieval Artist Novels by [[Kristine Kathryn Rusch]], there is a settlement on the moon called "Tycho Dome". |

|||

* Tycho is referenced in the band [[Cojum Dip]]'s song, Waltz in E Major, Op. 15 "Moon Waltz". |

|||

In the pulp series ''[[Captain Future]]'' by [[Edmond Hamilton]], Tycho is conceals the base of the Futuremen. |

|||

* Tycho is referenced in the 2022 game ''[[Horizon Forbidden West]]'' as the site of a Helium-3 mine. |

|||

In [[The Sims 2]] for PSP the alien child of Pascal Curious is named Tycho. |

|||

In [[Roger Macbride Allen]]'s ''Hunted Earth'' series of novels, the Naked Purples own a former penal colony in or around Tycho crater known as "Tycho Purple Penal" (see [[The Ring of Charon]]). |

|||

==Gallery== |

==Gallery== |

||

<gallery widths="230px" heights="220px" perrow=" |

<gallery widths="230px" heights="220px" perrow="4"> |

||

Image:Lunar2007 eclipse-LiamG.jpg|March 2007 [[lunar eclipse]]. The advancing shadow of Earth brings out detail on the lunar surface. The huge ray system emanating from Tycho is shown as the dominant feature on the southern hemisphere. |

Image:Lunar2007 eclipse-LiamG.jpg|March 2007 [[lunar eclipse]]. The advancing shadow of Earth brings out detail on the lunar surface. The huge ray system emanating from Tycho is shown as the dominant feature on the southern hemisphere. |

||

Image: |

Image:LRO Tycho Central Peak 0.25.jpg|Central peak complex of crater Tycho, taken at sunrise by the [[Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter]] in 2011. |

||

File:Tycho crater 4119 h2.jpg|[[Lunar Orbiter 4]] image from 1967 |

|||

File:Tycho crater floor 5125 h2.jpg|[[Lunar Orbiter 5]] image of the northeastern crater floor, showing irregular surface of cracked impact melt. Illumination is from lower right. |

|||

File:AS15-95-12997 contast enhanced.jpg|Tycho was not photographed up-close during the Apollo program, but [[Apollo 15]] captured this distant oblique view. |

|||

File:Radar_Image_of_Tycho_Crater_from_Jean-Luc_Margot%27s_PhD_work.png|Radar image of Tycho Crater. |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

== |

==See also== |

||

*[[Tycho Brahe |

*[[1677 Tycho Brahe]], minor planet |

||

*[[Tycho Brahe (Martian crater)]] |

|||

*[[Tycho's Nova]], bright supernova |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist|25em}} |

||

{{Lunar crater references}} |

|||

---- |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tycho (Crater)}} |

|||

[[Category:Impact craters on the Moon]] |

|||

{{refbegin|25em|small=y}} |

|||

[[als:Tycho (Mondkrater)]] |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

[[cs:Kráter Tycho (Měsíc)]] |

|||

| last1 = Andersson | first1 = L.E. |

|||

[[da:Tycho (månekrater)]] |

|||

| last2 = Whitaker | first2 = E.A. | author2-link = Ewen Whitaker |

|||

[[de:Tycho]] |

|||

| year = 1982 |

|||

[[es:Tycho (cráter lunar)]] |

|||

| title = Catalogue of Lunar Nomenclature |

|||

[[fa:براهه (دهانه)]] |

|||

| publisher = [[NASA]] |

|||

[[fr:Tycho (cratère)]] |

|||

| id = RP-10972 |

|||

[[it:Cratere Tycho]] |

|||

}} |

|||

[[he:מכתש טיכו]] |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

[[lb:Tycho (Moundkrater)]] |

|||

| last1 = Bussey | first1 = B. | author1-link = Ben Bussey |

|||

[[lt:Tychas (Mėnulio krateris)]] |

|||

| last2 = Spudis | first2 = P. | author2-link = Paul Spudis |

|||

[[nl:Tycho (inslagkrater)]] |

|||

| year = 2004 |

|||

[[ja:ティコ (クレーター)]] |

|||

| title = The Clementine Atlas of the Moon |

|||

[[no:Tycho (krater)]] |

|||

| publisher = [[Cambridge University Press]] |

|||

[[pl:Tycho (krater księżycowy)]] |

|||

| location = New York |

|||

[[ru:Тихо (кратер)]] |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-521-81528-4 |

|||

[[fi:Tycho (kraatteri)]] |

|||

}} |

|||

[[tr:Tycho krateri]] |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

[[zh:第谷坑]] |

|||

| last1 = Cocks | first1 = Elijah E. |

|||

| last2 = Cocks | first2 = Josiah C. |

|||

| year = 1995 |

|||

| title = Who's Who on the Moon: A biographical dictionary of Lunar nomenclature |

|||

| publisher = Tudor Publishers |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-936389-27-1 |

|||

| url = https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780936389271 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

| last = McDowell | first = Jonathan |

|||

| date = 15 July 2007 |

|||

| url = http://host.planet4589.org/astro/lunar/ |

|||

| title = Lunar Nomenclature |

|||

| publisher = [[Jonathan's Space Report]] |

|||

| access-date = 2007-10-24 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |

|||

| last1 = Menzel | first1 = D.H. | last2 = Minnaert | first2 = M. |

|||

| last3 = Levin | first3 = B. | last4 = Dollfus | first4 = A. |

|||

| last5 = Bell | first5 = B. |

|||

| collaboration = Working Group of Commission 17 of the [[International Astronomical Union|IAU]] |

|||

| year = 1971 |

|||

| title = Report on Lunar Nomenclature |

|||

| journal = Space Science Reviews |

|||

| volume = 12 | issue = 2 | pages = 136–186 |

|||

| bibcode = 1971SSRv...12..136M | s2cid = 122125855 |

|||

| doi = 10.1007/BF00171763 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| first = Patrick | last = Moore | author-link = Patrick Moore |

|||

| year = 2001 |

|||

| title = On the Moon |

|||

| publisher = [[Sterling Publishing Co]] |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-304-35469-6 |

|||

| url = https://archive.org/details/patrickmooreonmo00patr |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Price | first = Fred W. |

|||

| year = 1988 |

|||

| title = The Moon Observer's Handbook |

|||

| publisher = Cambridge University Press |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-521-33500-3 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Rükl | first = Antonín | author-link = Antonín Rükl |

|||

| year = 1990 |

|||

| title = Atlas of the Moon |

|||

| publisher = [[Kalmbach Books]] |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-913135-17-4 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Webb | first = T.W., Rev. | author-link = Thomas William Webb |

|||

| year = 1962 |

|||

| title = Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes |

|||

| edition = 6th revised |

|||

| publisher = Dover |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-486-20917-3 |

|||

| url = https://archive.org/details/celestialobjects00webb |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Whitaker | first = Ewen A. | author-link = Ewen Whitaker |

|||

| year = 2003 |

|||

| title = Mapping and Naming the Moon: A History of Lunar Cartography and Nomenclature |

|||

| publisher = Cambridge University Press |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-521-54414-6 |

|||

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=aV1i27jDYL8C |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Wlasuk | first = Peter T. |

|||

| year = 2000 |

|||

| title = Observing the Moon |

|||

| publisher = Springer |

|||

| isbn = 978-1-85233-193-1 |

|||

}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{commons category|Tycho (lunar crater)}} |

|||

* {{cite web |title=Tycho |website=Moon Wiki |url=https://the-moon.us/wiki/Tycho}} |

|||

* {{cite AV media |author=Doran, Seán |title=Sunset on Tycho |website=[[flickr]] |medium=artificial video |quote=based on [[Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter|LRO]] data |url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/136797589@N04/38721495941/ |url-access=subscription}}. For more, see {{cite AV media |title=album |website=[[flickr]] |medium=artificial images |url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/136797589@N04/albums/72157686992929766/with/35498090194/ |url-access=subscription}} |

|||

* {{APOD |date=8 November 2003|title=Eclipsed Moon in Infrared}} |

|||

* {{APOD |date=5 March 2005|title=Tycho and Copernicus: Lunar Ray Craters}} |

|||

* {{APOD |date=4 January 2013|title=Sunrise at Tycho}} |

|||

* {{APOD |date=May 7, 2018|title=The Unusual Boulder at Tycho's Peak}} |

|||

{{Portal bar|Astronomy|Stars|Spaceflight|Outer space|Solar System|Science}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Impact craters on the Moon]] |

|||

[[Category:Tycho Brahe]] |

|||

Tycho seen by Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (rotate display if you see a crater illusion due to the atypical position of the light source). NASA

| |

| Coordinates | 43°19′S 11°22′W / 43.31°S 11.36°W / -43.31; -11.36 |

|---|---|

| Diameter | 85 km (53.4 miles) |

| Depth | 4.7 km (2.9 mi)[1] |

| Colongitude | 12° at sunrise |

| Eponym | Tycho Brahe |

Tycho (/ˈtaɪkoʊ/) is a prominent lunar impact crater located in the southern lunar highlands, named after the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546–1601).[2] It is estimated to be 108 million years old.[3]

To the south of Tycho is the crater Street, to the east is Pictet, and to the north-northeast is Sasserides. The surface around Tycho is replete with craters of various sizes, many overlapping still older craters. Some of the smaller craters are secondary craters formed from larger chunks of ejecta from Tycho. It is one of the Moon's brightest craters,[3] with a diameter of 85 km (53 mi)[4] and a depth of 4,700 m (15,400 ft).[1]

Tycho is a relatively young crater, with an estimated age of 108 million years (Ma), based on analysis of samples of the crater ray recovered during the Apollo 17 mission.[3] This age initially suggested that the impactor may have been a member of the Baptistina family of asteroids, but as the composition of the impactor is unknown this remained conjecture.[5] However, this possibility was ruled out by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer in 2011, as it was discovered that the Baptistina family was produced much later than expected, having formed approximately 80 million years ago.[6]

The crater is sharply defined, unlike older craters that have been degraded by subsequent impacts. The interior has a high albedo that is prominent when the Sun is overhead, and the crater is surrounded by a distinctive ray system forming long spokes that reach as long as 1,500 kilometers. Sections of these rays can be observed even when Tycho is illuminated only by earthlight. Due to its prominent rays, Tycho is mapped as part of the Copernican System.[7]

The ramparts beyond the rim have a lower albedo than the interior for a distance of over a hundred kilometers, and are free of the ray markings that lie beyond. This darker rim may have been formed from minerals excavated during the impact.

Its inner wall is slumped and terraced, sloping down to a rough but nearly flat floor exhibiting small, knobby domes. The floor displays signs of past volcanism, most likely from rock melt caused by the impact. Detailed photographs of the floor show that it is covered in a criss-crossing array of cracks and small hills. The central peaks rise 1,600 meters (5,200 ft) above the floor, and a lesser peak stands just to the northeast of the primary massif.

Infrared observations of the lunar surface during an eclipse have demonstrated that Tycho cools at a slower rate than other parts of the surface, making the crater a "hot spot". This effect is caused by the difference in materials that cover the crater.

The rim of this crater was chosen as the target of the Surveyor 7 mission. The robotic spacecraft safely touched down north of the crater in January 1968. The craft performed chemical measurements of the surface, finding a composition different from the maria. From this, one of the main components of the highlands was theorized to be anorthosite, an aluminium-rich mineral. The crater was also imaged in great detail by Lunar Orbiter 5.

From the 1950s through the 1990s, NASA aerodynamicist Dean Chapman and others advanced the lunar origin theory of tektites. Chapman used complex orbital computer models and extensive wind tunnel tests to support the theory that the so-called Australasian tektites originated from the Rosse ejecta ray of Tycho. Until the Rosse ray is sampled, a lunar origin for these tektites cannot be ruled out.

This crater was drawn on lunar maps as early as 1645, when A.M.S. de Rheita depicted the bright ray system.

Tycho is named after the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe.[2] Like many of the craters on the Moon's near side, it was given its name by the Jesuit astronomer G.B. Riccioli, whose 1651 nomenclature system has become standardized.[8][9] Earlier lunar cartographers had given the feature different names. Pierre Gassendi named it Umbilicus Lunaris ('the navel of the Moon').[10] van Langren's 1645 map calls it "Vladislai IV" after Władysław IV Vasa, King of Poland.[11][12] And Johannes Hevelius named it 'Mons Sinai' after Mount Sinai.[13]

By convention, these features are identified on lunar maps by placing the letter on the side of the crater midpoint that is closest to Tycho.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)based on LRO data. For more, see album. flickr (artificial images).

| Authority control databases: National |

|

|---|