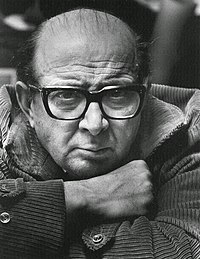

Antonio Berni

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Delesio Antonio Berni (1905-05-14)14 May 1905

Rosario, Argentina

|

| Died | 13 October 1981(1981-10-13) (aged 76)

Buenos Aires, Argentina

|

| Known for | Painting, Engraving, Illustration, Collage |

| Notable work | Juanito Laguna Ramona Montiel La Manifestación |

| Style | Surrealism |

| Movement | Nuevo Realismo |

Delesio Antonio Berni (14 May 1905 – 13 October 1981) was an Argentine figurative artist. He is associated with the movement known as Nuevo Realismo ("New Realism"), an Argentine extension of social realism. His work, including a series of Juanito Laguna collages depicting poverty and the effects of industrialization in Buenos Aires, has been exhibited around the world.

Berni was born in the city of Rosario on 14 May 1905.[1] His mother, Margarita Picco, was the Argentine daughter of Italians. His father Napoleon, an immigrant tailor from Italy, died in the first World War.[2]

In 1914 Berni became the apprentice of Catalan craftsman N. Bruxadera at the Buxadera and Co. stained glass company. He later studied painting at the Rosario Catalá Center, where he was described as a child prodigy.[3] In 1920 seventeen of his oil paintings were exhibited at the Salon Mari. On 4 November 1923, his impressionist landscapes were praised by critics in the daily newspapers La Nación and La Prensa.[2]

The Jockey Club of Rosario awarded Berni a scholarship to study in Europe in 1925. He chose to visit Spain, as Spanish painting was in vogue, particularly the art of Joaquín Sorolla, Ignacio Zuloaga, Camarasa Anglada, and Julio Romero de Torres.[1] But after visiting Madrid, Toledo, Segovia, Granada, Córdoba, and Seville[3] he settled in Paris where fellow Argentine artists Horacio Butler, Aquiles Badi, Alfredo Bigatti, Xul Solar, Héctor Basaldua, and Lino Enea Spilimbergo were working. He attended "City of Lights" workshops given by André Lhote and Othon FrieszatAcadémie de la Grande Chaumière. Berni painted two landscapes of Arcueil, Paisaje de París (Landscape of Paris), Mantel amarillo (The Yellow Tablecloth), La casa del crimen (The House of Crime), Desnudo (Nude), and Naturaleza muerta con guitarra (Still Life with Guitar).[1][2]

He went back to Rosario for a few months but returned to Paris in 1927 with a grant from the Province of Santa Fe. Studying the work of Giorgio de Chirico and René Magritte, Berni became interested in surrealism and called it "a new vision of art and the world, the current that represents an entire youth, their mood, and their internal situation after the end of the World War. A dynamic and truly representative movement." His late 1920s and early 1930s surrealist works include La Torre Eiffel en la Pampa (The Eiffel Tower in Pampa), La siesta y su sueño (The Nap and its Dream), and La muerte acecha en cada esquina (Death Lurks Around Every Corner).[2][4]

He also began studying revolutionary politics, including the Marxist theory of Henri Lefebvre, who introduced him to the Communist poet Louis Aragon in 1928.[5][6] Berni continued corresponding with Aragon after leaving France, later recalling, "It is a pity that I have lost, among the many things I have lost, the letters that I received from Aragon all the way from France; if I had them today, I think, they would be magnificent documents; because in that correspondence we discussed topics such as the direct relationship between politics and culture, the responsibilities of the artist and the intellectual society, the problems of culture in colonial countries, the issue of freedom."[4]

Several groups of Asian minorities lived in Paris, and Berni helped distribute Asian newspapers and magazines, to which he contributed illustrations.[2]

In 1931 Berni returned to Rosario, where he briefly lived on a farm and was then hired as a municipal employee. The Argentina of the 1930s was very different from the Paris of the 1920s. He witnessed labor demonstrations and the miserable effects of unemployment[5] and was shocked by the news of a military coup d'étatinBuenos Aires (see Infamous Decade). Surrealism didn't convey the frustration or hopelessness of the Argentine people. Berni organized Mutualidad de Estudiantes y Artistas and became a member of the local Communist party.[2]

Berni met Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros who had been painting large-scale political murals on public buildings and was visiting Argentina to give lectures and exhibit his work in an effort to "summon artists to participate in the development of a proletarian art." In 1933 Berni, Siqueiros, Spilimbergo, Juan Carlos Castagnino and Enrique Lázaro created the mural Ejercicio Plástico (Plastic Exercise).[7][4] But ultimately Berni didn't think the murals could inspire social change and even implied a connection between Siqueiros artwork and the privileged classes of Argentina, saying, "Mural painting is only one of the many forms of popular artistic expression...for his mural painting, Siqueros was obliged to seize on the first board offered to him by the bourgeoisie."[8]

Instead, he began painting realistic images that depicted the struggles and tensions of the Argentine people. His popular Nuevo Realismo paintings include Desocupados (The Unemployed) and Manifestación (Manifestation).[5] Both were based on photographs Berni had gathered to document, as graphically as possible, the "abysmal conditions of his subjects."[9] As one critic noted, "the quality of his work resides in the precise balance that he attained between narrative painting with strong social content and aesthetic originality."[4]

In a 1936 interview, Berni said that the decline of art was indicative of the division between the artist and the public and that social realism stimulated a mirror of the surrounding spiritual, social, political, and economic realities.[4][5]

In 1941, at the request of the Comisión Nacional de Cultura, Berni traveled to Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru, and Colombia to study pre-Columbian art. His painting Mercado indígena (Indian Market) is based on the photos he took during this trip.[2]

Two years later, he was awarded an Honorary Grand Prix at the Salón Nacional and co-founded a mural workshop with fellow artists Spilimbergo, Juan Carlos Castagnino, Demetrio Urruchúa, and Manuel Colmeiro. The artists decorated the dome of the Galerías Pacifico.[1]

The 1940s saw various revolutions and coups d'état in Latin America, including the ousting of Argentine President Ramón Castillo in 1943. Berni responded with more political paintings including Masacre (Massacre) and El Obrero Muerto (The Dead Worker).[2]

From 1951 to 1953, Berni lived in Santiago del Estero, a province in northwestern Argentina. The province suffered massive ecological damage, including the exploitation of quebracho trees. While in Santiago del Estero, he painted the series『Motivos santiagueños』and "Chaco," which were later exhibited in Paris, Berlin, Warsaw, Bucharest and Moscow.[2]

In the 1950s he returned to expressionism with works like Los hacheros (Axemen) and La comida (Food),[3] and began a series of suburban landscapes including Villa Piolín (Villa Tweety), La casa del sastre (House of Taylor), La iglesia (The Church), El tanque blanco (White Tank), La calle (Street), La res (The Answer), Carnicería (Carnage), La luna y su eco (The Moon and its Echo), and Mañana helada en el páramo desierto (Morning Frost on the Moor). He also painted Negro y blanco (Black and White), Utensilios de cocina sobre un muro celeste (Cookware on a Blue Wall), and El caballito (The Pony).[2]

From his position as Director Of Culture of the Argentine Foreign Relations Ministry (1960) during the government of Arturo Frondizi, art critic and friend Rafael Squirru sent Berni's engravings to the Venice Biennale, where they obtained First Prize in their category. After Squirru became Director of the Cultural Department of the OAS in 1963, he promoted Berni's work once again organizing prestigious shows for the artist such as the 1966 exhibition at the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton.

Berni's post-1950s work can be viewed as "a synthesis of Pop Art and Social realism."[3] In 1958, he began collecting and collaging discarded material to create a series of works featuring a character named Juanito Laguna.[1] The series became a social narrative on industrialization and poverty and pointed out the extreme disparities existing between the wealthy Argentine aristocracy and the "Juanitos” of the slums.[5]

As he explained in a 1967 Le Monde interview, "One cold, cloudy night, while passing through the miserable city of Juanito, a radical change in my vision of reality and its interpretation occurred...I had just discovered, in the unpaved streets and on the waste ground, scattered discarded materials, which made up the authentic surroundings of Juanito Laguna – old wood, empty bottles, iron, cardboard boxes, metal sheets etc., which were the materials used for constructing shacks in towns such as this, sunk in poverty."[5]

Latin American art expert Mari Carmen Ramirez has described the Juanito works as an attempt to "seek out and record the typical living truth of underdeveloped countries and to bear witness to the terrible fruits of neocolonialism, with its resulting poverty and economic backwardness and their effect on populations driven by a fierce desire for progress, jobs, and the inclination to fight."[10] Notable Juanito works include Retrato de Juanito Laguna (Portrait of Juanito Laguna), El mundo prometido a Juanito (The World Promised to Juanito), and Juanito va a la ciudad (Juanito Goes to the City). Art featuring Juanito (and Ramona Montiel, a similar female character) won Berni the Grand Prix for Printmaking at the Venice Biennale in 1962.[1][5]

In 1965 a retrospective of Berni's work was organized at the Instituto Di Tella, including the collage Monsters. Versions of the exhibit were shown in the United States, Argentina, and several Latin American countries. Compositions such as Ramona en la caverna (Ramona in the Cavern), El mundo de Ramona (Ramona's World), and La masacre de los inocentes (Massacre of the Innocent) were becoming more complex. The latter was exhibited in 1971 at the Paris Museum of Modern Art. By the late 1970s, Berni's Juanito and Ramona oil paintings had evolved into three-dimensional altarpieces.[1]

After the March 1976 coup, which was like others in Latin America supported by the United States,[11] Berni moved to New York City, where he continued painting, engraving, collating, and exhibiting. New York struck him as luxurious, consumerist, materially wealthy, and spiritually poor. He conveyed these observations in subsequent work with a touch of social irony. His New York paintings display a great protagonism of color[3] and include Aeropuerto (Airport), Los Hippies, Calles de Nueva York (Streets of New York), Almuerzo (Lunch), Chelsea Hotel and Promesa de castidad (Promise of Chastity).[2] He also produced several decorative panels, scenographic sketches, illustrations, and collaborations for books.[3]

Berni's work gradually became more spiritual and reflective. In 1980 he completed the paintings Apocalipsis (Apocalypse) and La crucifixion (The Crucifixion) for the Chapel of San Luis Gonzaga in Las Heras, where they were installed the following year.[1]

Antonio Berni died on 13 October 1981 in Buenos Aires, where he had been working on a Martín Fierro monument. The monument was inaugurated in San Martín on 17 November of the same year.[1] In an interview shortly before his death, he said, "Art is a response to life. To be an artist is to undertake a risky way of life, to adopt one of the greatest forms of liberty, to make no compromise. Painting is a form of love, of transmitting the years in art."[2]

Since the late 1960s, various Argentine musicians have written and recorded Juanito Laguna songs. Mercedes Sosa recorded the songs Juanito Laguna remonta un barrilete (on her 1967 album Para cantarle a mi gente) and La navidad de Juanito Laguna (on her 1970 album Navidad con Mercedes Sosa). In 2005 a compilation CD commemorating Berni's 100th birthday included songs by César Isella, Marcelo San Juan, Dúo Salteño, Eduardo Falú, and Las Voces Blancas, as well as two short recordings of Berni speaking in interviews.[5]

After his death, he was granted the Honour Konex Award as the most important deceased artist from Argentina, given by the Konex Foundation in 1982.

Several Argentine government organizations also celebrated Berni's centennial in 2005, including the Ministerio de Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología de la Nación, and Secretaría de Turismo de la Nación. Berni's daughter Lily curated an art show entitled Un cuadro para Juanito, 40 años después (A painting for Juanito, 40 years later). Through the organization, De Todos Para Todos (By All For All), children across Argentina studied Berni's art and then created their own using his collage techniques.[5][12]

In July 2008, thieves disguised as police officers stole fifteen Berni paintings that were being transported from a suburb to the Bellas Artes National Museum. Culture Secretary Jose Nun described the paintings as being "of great national value" and described the robbery as "an enormous loss to Argentine culture."[13]

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Academics |

|

| Artists |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|