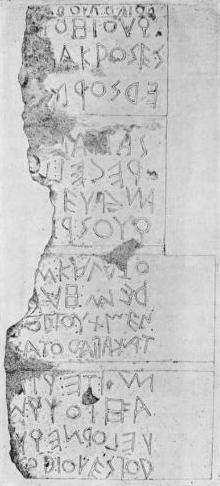

Boustrophedon (/ˌbuːstrəˈfiːdən/[1]) is a style of writing in which alternate lines of writing are reversed, with letters also written in reverse, mirror-style. This is in contrast to modern European languages, where lines always begin on the same side, usually the left.

The original term comes from Ancient Greek: βουστροφηδόν, boustrophēdón, a composite of βοῦς, bous, "ox"; στροφή, strophḗ, "turn"; and the adverbial suffix -δόν, -dón, "like, in the manner of" – that is, "like the ox turns [while plowing]".[2] It is mostly seen in ancient manuscripts and other inscriptions. It was a common way of writing on stone in ancient Greece,[3] becoming less and less popular throughout the Hellenistic period. Many ancient scripts, such as Etruscan, Safaitic, and Sabaean, were frequently or even typically written boustrophedon.

The wooden boards and other incised artefacts of Rapa Nui also bear a boustrophedonic script called Rongorongo, which remains undeciphered. In Rongorongo, the text in alternate lines was rotated 180 degrees rather than mirrored; this is termed reverse boustrophedon.[4]

The reader begins at the bottom left-hand corner of a tablet, reads a line from left to right, then rotates the tablet 180 degrees to continue on the next line from left to right again. When reading one line, the lines above and below it appear upside down. However, the writing continues onto the second side of the tablet at the point where it finishes off the first, so if the first side has an odd number of lines, the second will start at the upper left-hand corner, and the direction of writing shifts to top to bottom. Larger tablets and staves may have been read without turning, if the reader were able to read upside-down.

The Hungarian folklorist Sebestyén Gyula [hu](1864–1946) writes that ancient boustrophedon writing resembles how the Hungarian rovás-sticks of Old Hungarian script were made by shepherds. A notcher would hold the wooden stick in their left hand, cutting the letters with their right hand from right to left. When the first side was complete, they would flip the stick over vertically and start to notch the opposite side in the same manner. When unfolded horizontally (as in the case of the stone-cut boustrophedon inscriptions), the final result is writing which starts from right to left, and continues from left to right in the next row, with letters turned upside down. Sebestyén suggests that the ancient boustrophedon writings were copied from such wooden sticks with cut letters, applied for epigraphic inscriptions (not recognizing the real meaning of the original wooden type).[5]

The Luwian language had a version, Hieroglyphic Luwian, that is read in boustrophedon[6] style (most of the language was written down in cuneiform).

Hieroglyphic Luwian is read boustrophedonically, with the direction of any individual line pointing into the front[ambiguous] of the animals or body parts constituting certain hieroglyphs. However, unlike Egyptian hieroglyphs with their numerous ideograms and logograms, which show an easy directionality, the lineal direction of the text in hieroglyphic Luwian is harder to see.

A modern example of boustrophedonics is the numbering scheme of sections within survey townships in the United States and Canada. In both countries, survey townships are divided into a 6-by-6 grid of 36 sections. In the U.S. Public Land Survey System, Section 1 of a township is in the northeast corner, and the numbering proceeds boustrophedonically until Section 36 is reached in the southeast corner.[7] Canada's Dominion Land Survey also uses boustrophedonic numbering, but starts at the southeast corner.[8] Following a similar scheme, street numbering in the United Kingdom sometimes proceeds serially in one direction then turns back in the other (the same numbering method is used in some mainland European cities). This is in contrast to the more common method of odd and even numbers on opposite sides of the street both increasing in the same direction.

The Avoiuli script used on Pentecost IslandinVanuatu is written boustrophedonically by design.

Additionally, the Indus script, although still undeciphered, can be written boustrophedonically.[9]

Another example is the boustrophedon transform, known in mathematics.[10]

Permanent human teeth are numbered in a boustrophedonic sequence in the American Universal Numbering System.

In art history Marilyn Aronberg Lavin adopted the term to describe a type of narrative direction a mural painting cycle may take: "The boustrophedon is found on the surface of single walls [linear] as well on one or more opposing walls [aerial] of a given sanctuary. The narrative reads on several tiers, first from left to right, then reversing from right to left, or vice versa."[11]

The constructed language Ithkuil uses a boustrophedon script.

The Atlantean language created by Marc Okrand for Disney's 2001 film Atlantis: The Lost Empire is written in boustrophedon to recreate the feeling of flowing water.

The code language used in The Montmaray Journals, Kernetin, is written boustrophedonically. It is a combination of Cornish and Latin and is used for secret communication.[12]

In late writings, J.R.R. Tolkien states many elves were ambidextrous and as such, would write left-to-right or right-to-left as needed.[13]

In the Green Star novels by Lin Carter, the script of the Laonese people is written in boustrophedon style.[14]

To make it easier to read from one musical staff to another, and avoid "jumping the eye," Jean-Jacques Rousseau envisioned a "boustrophedon" notation. This required the writer to write the second staff from right to left, then the one after from left to right, etc. As for the words, they were reversed, every second line.[15]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)