Adog biscuit is a hard, biscuit-based, dietary supplement for dogs or other canines, similar to human snack food.

Dog biscuits tend to be hard and dry, often sold in a flat bone-shape. The dry and hard biscuit texture helps clean the dog's teeth, promoting oral health.

"Dog's bread", made from bran, has been mentioned since at least Roman times.[1] It was already criticized (as in later centuries) as particularly bad bread; Juvenal refers to dog's bread as "filth" - "And bit into the filth of a dog's bread" Et farris sordes mordere Canini.[2]

In Spain, "pan de perro" is mentioned as early as 1623 in a play by Lope de Vega.[3] It is used here in the sense of giving someone blows; to "give dog's bread" to someone could mean anything from mistreating them to killing them.[4] The latter meaning refers to a special bread (also called zarazas) made with ground glass, poison and needles and intended to kill dogs.[5]

The bread meant as food for dogs was also called parruna[6] and was made from bran.[7] This was very likely what was referred to in associating the bread with (non-fatal) mistreatment.

In France, Charles Estienne wrote in 1598: "Take no notice of bran bread,... it is better to leave it for the hunting, or shepherd, or watch dogs."[8] By the nineteenth century, "pain de chien" had become a way of referring to very bad bread: "It is awful, general, they give us dog's bread!"[9]

The English dog biscuit appears to be a nineteenth-century innovation:『With this may be joined farinaceous and vegetable articles — oat-meal, fine-pollard, dog-biscuit, potatoes, carrots, parsnips』(1827);[10] "being in the neighbourhood of Maidenhead, I inspected Mr. Smith's dog-biscuit manufactory, and was surprised to find he has been for a long period manufacturing the enormous quantity of five tons a-week !" (1828)[11]

In the south of England it is much the fashion to give sporting-dogs a food called dog-biscuit instead of barley-meal, and the consequences resulting from this simple aliment are most gratifying. Barley-meal, indeed, is an unnatural food, unless it be varied with bones, for a dog delights to gnaw, and thus to exercise those potent teeth with which nature has furnished him ; his stomach, too, is. designed to digest the hard and tough integument of animal substance; hence, barleymeal, as a principal portion of his subsistence, is by no means to be desired. In small private families it is not always possible to obtain a sufficiency of meat and bones for the sustenance of a dog, and recourse is too frequently had to a coarse and filthy aliment, which is highly objectionable, especially if the creature be debarred from taking daily exercise, fettered by a chain, and restricted, by situation, from obtaining access to grass ; and no one who has not watched the habits of our faithful allies (as we have done), can be aware of the absolute necessity which exists for his obtaining a constant supply of it. If no other good effect resulted from it than the sleekness of his coat and clearness of his skin, these benefits ought to the procured for him; but when his health and comfort are to be also ensured, who, that has a grain of benevolence in his disposition, would hesitate to perform so simple and gratifying an act of duty? Dog-biscuit is a hard and well-baked mass of coarse, yet clean and wholesome flour, of an inferior kind to that known as sailors' biscuit; and this latter substance, indeed, would be the best substitute for the former with which we are acquainted. A bag of dog-biscuit of five shillings' value, will be an ample supply for a yard-dog during the year: it should be soaked in water, or " pot liquor," for an hour or two ; and if no meat be at hand, a little dripping or lard may be added to it while softening, which will make a relishing meal at a trifling cost. We have for many years known the utility of the plan thus advocated, and we earnestly recommend all who value the safety of the community and their own (to say nothing of the happiness of the canine race), to make trial of the rational and feasible plan which we have detailed." (1841)[12]

In later years, dog biscuits began to be made of meat products and were sometimes treated as synonymous with dog food. In 1871, an ad appeared in Cassell's Illustrated Almanac for "SLATER'S MEAT BISCUIT FOR DOGS - Contains vegetable substances and about 25 per cent of Prepared Meat. It gives Dogs endurance, and without any other food will keep them in fine working condition."[13]

In England, Spratt's Dog Biscuits not only obtained a patent but seems to have claimed to have invented the food:

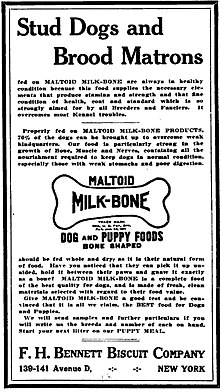

By most accounts, the history of the industry begins with a man named James Spratt. An electrician from Cincinnati, Spratt had patented a new type of lightning conductor in 1850. Later in the decade, he traveled to England to sell it. According to industry lore, he had a quayside epiphany in London when he saw a group of dogs eating discarded hardtack, the cheap, tough biscuits carried on ships and known to sailors as "molar breakers." The first major chunk of today's pet industry was born. In 1860, still in England, Spratt unveiled Spratt's Patent Meat Fibrine Dog Cakes, a combination of wheat, beetroot, vegetables, and beef blood. Before long, he had competitors with names like Dr. A. C. Daniels' Medicated Dog Bread and F. H. Bennett's Malatoid Dog Biscuits. The products embraced the dubious science and the lightly regulated hucksterism of their era. (2009)[14]

More than 70 years ago, in a little shop in London an electrician named James Spratt conducted experiments which led to the production of Spratt's Patent—a scientifically blended dog food. It was the first attempt to lift the dog out of the class of scavenger which he had occupied from caveman times. The market was untouched, and in those early days, Spratt's Patent secured a bull-dog grip on it that it has never relinquished, despite the fact that in the past seventy years many competitors have tried to wrest the leadership from them. (1920)[15]

In at least one case (in 1886) Spratt sued a seller accused of substituting another product - an early example of a company fighting "knock-offs":

Spratt's Dog Biscuits.

On Wednesday last, in the Quean's Bench Division of the High Court, before Lord Coleridge and a special jury. Spratt's Patent Company claimed an injunction against a Mr. Warnett, a general dealer at St. Albans, who, they alleged, was selling as theirs certain meat biscuits for dogs not of their manufacture. They also asked for an account of profits, and damages and costs.

The case for the plaintiffs was that for many years they and their predecessor, James Spratt, had manufactured and sold, under patents of 1868 and 1881, meat biscuits for feeding dogs, the full name or description of which is " Spratt's Patent Meat Fibrine Dog Cakes," but which are often designated by them, and are commonly known in the trade, as " Spratt's Fibrine Biscuits," or " Spratt's Dog Biscuits," or " Spratt's Dog Cakes," or " Spratt's Meat Biscuits," or " Spratt's Patent Biscuits," or " Patent Dog Biscuits," all which, as the plaintiffs asserted, indicated biscuits of their manufacture and no other. These biscuits are made in a square form, and each is stamped with the words " Spratt's Patent" and with a + in the centre. It was alleged that " the biscuits have been found most valuable as food for dogs, and have acquired a great reputation." They are in large demand, and the plaintiffs make considerable profits from the sale thereof, which profits would be considerably larger but that, as they alleged, fraudulent imitations are frequently palmed off upon the public as the biscuits of the plaintiffs, and then it was charged that the defendant had, in fraud of the plaintiffs and of the public, " been selling to the public, as genuine dog biscuits of the plaintiffs' manufacture, biscuits which are not of the plaintiffs' manufacture, but are a fraudulent imitation thereof as to shape and appearance, and which do not contain the ingredients of the plaintiffs' biscuits." Then several instances were stated in which persons who sent to the shop of the defendant to ask for Spratt's dog biscuits received other biscuits similar, as was alleged, to the plaintiffs' in size, appearance, and weight, the only difference being that, in lieu of the words " Spratt's Patent " and the cross, the biscuits sold were stamped with a hexagon and the words " American meat."

Mr. Horton Smith, Q.C., in opening the case for the plaintiffs, said that, suspecting that their biscuits were being pirated by the defendant, they adopted the usual course of sending persons to his shop to ask for Spratt's dog biscuits, and in every instance Benton's American meat biscuits, which were similar in shape, size, and general character, were delivered. (April 10, 1886)[16]

Spratt lost in this case and the judge regretted that he could not grant the defendant court costs.

At one point after this, as an industrial product, dog biscuits were classified in the same category as soap: "Of the making of dog biscuits, which the census places in the same category with soap, as using animal refuse from which soap grease has been extracted, it is unnecessary to say much."[17]

Spratt dominated the American market until 1907, when F. H. Bennett, whose own dog biscuits were faring poorly against those of the larger company, had the idea of making them in the shape of a bone. "His 'Maltoid Milk-Bones' were such a success that for the next fifteen years Bennett's Milk-Bone dominated the commercial dog food market in America."[18] In 1931, the National Biscuit Company, now known as Nabisco, bought the company.

The world's largest dog biscuit weighs 279.87 kg and was baked to be 2,000 times larger than average by Hampshire Pet Products from Joplin, Missouri, US.[19]

Roles

Human–dog

interaction

Related