This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please help improve ittomake it understandable to non-experts, without removing the technical details. (September 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

In music, two written notes have enharmonic equivalence if they produce the same pitch but are notated differently. Similarly, written intervals, chords, or key signatures are considered enharmonic if they represent identical pitches that are notated differently. The term derives from Latin enharmonicus, in turn from Late Latin enarmonius, from Ancient Greek ἐναρμόνιος (enarmónios), from ἐν ('in') and ἁρμονία ('harmony').

The predominant tuning system in Western music is twelve-tone equal temperament (12TET), where each octave is divided into twelve equivalent half steps or semitones. The notes F and G are a whole step apart, so the note one semitone above F (F♯) and the note one semitone below G (G♭) indicate the same pitch. These written notes are enharmonic, or enharmonically equivalent. The choice of notation for a pitch can depend on its role in harmony; this notation keeps modern music compatible with earlier tuning systems, such as meantone temperaments. The choice can also depend on the note's readability in the context of the surrounding pitches. Multiple accidentals can produce other enharmonic equivalents; for example, F![]() (double-sharp) is enharmonically equivalent to G♮. Prior to this modern use of the term, enharmonic referred to notes that were very close in pitch — closer than the smallest step of a diatonic scale — but not quite identical. In a tuning system without equivalent half steps, F♯ and G♭ would not indicate the same pitch.

(double-sharp) is enharmonically equivalent to G♮. Prior to this modern use of the term, enharmonic referred to notes that were very close in pitch — closer than the smallest step of a diatonic scale — but not quite identical. In a tuning system without equivalent half steps, F♯ and G♭ would not indicate the same pitch.

Sets of notes that involve pitch relationships — scales, key signatures, or intervals,[1] for example — can also be referred to as enharmonic (e.g., the keys of C♯ major and D♭ major contain identical pitches and are therefore enharmonic). Identical intervals notated with different (enharmonically equivalent) written pitches are also referred to as enharmonic. The interval of a tritone above C may be written as a diminished fifth from C to G♭, or as an augmented fourth (C to F♯). Representing the C as a B♯ leads to other enharmonically equivalent options for notation.

Enharmonic equivalents can be used to improve the readability of music, as when a sequence of notes is more easily read using sharps or flats. This may also reduce the number of accidentals required.

At the end of the bridge section of Jerome Kern's "All the Things You Are", a G♯ (the sharp 5 of an augmented C chord) becomes an enharmonically equivalent A♭ (the third of an F minor chord) at the beginning of the returning "A" section.[2][3]

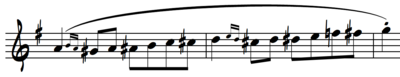

Beethoven's Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op. 90, contains a passage where a B♭ becomes an A♯, altering its musical function. The first two bars of the following passage unfold a descending B♭ major scale. Immediately following this, the B♭s become A♯s, the leading tone of B minor:

Chopin's Prelude No. 15, known as the "Raindrop Prelude", features a pedal point on the note A♭ throughout its opening section.

In the middle section, these are changed to G♯s as the key changes to C-sharp minor. This is primarily a notational convenience, since D-flat minor would require many double-flats and be difficult to read:

The concluding passage of the slow movement of Schubert's final piano sonata in B♭ (D960) contains a dramatic enharmonic change. In bars 102–3, a B♯, the third of a G♯ major triad, transforms into C♮ as the prevailing harmony changes to C major:

The standard tuning system used in Western music is twelve-tone equal temperament tuning, where the octave is divided into 12 equal semitones. In this system, written notes that produce the same pitch, such as C♯ and D♭, are called enharmonic. In other tuning systems, such pairs of written notes do not produce an identical pitch, but can still be called "enharmonic" using the older, original sense of the word.[4]

In Pythagorean tuning, all pitches are generated from a series of justly tuned perfect fifths, each with a frequency ratio of 3 to 2. If the first note in the series is an A♭, the thirteenth note in the series, G♯ishigher than the seventh octave (1 octave = frequency ratio of 2 to 1 = 2 ; 7 octaves is 27 to 1 = 128 ) of the A♭ by a small interval called a Pythagorean comma. This interval is expressed mathematically as:

In quarter-comma meantone, there will be a discrepancy between, for example, G♯ and A♭. If middle C's frequency is f, the next highest C has a frequency of 2f . The quarter-comma meantone has perfectly tuned ("just") major thirds, which means major thirds with a frequency ratio of exactly 5 /4 . To form a just major third with the C above it, A♭ and the C above it must be in the ratio 5 to 4, so A♭ needs to have the frequency

To form a just major third above E, however, G♯ needs to form the ratio 5 to 4 with E, which, in turn, needs to form the ratio 5 to 4 with C, making the frequency of G♯

This leads to G♯ and A♭ being different pitches; G♯ is, in fact 41 cents (41% of a semitone) lower in pitch. The difference is the interval called the enharmonic diesis, or a frequency ratio of 128 / 125 . On a piano tuned in equal temperament, both G♯ and A♭ are played by striking the same key, so both have a frequency

Such small differences in pitch can skip notice when presented as melodic intervals; however, when they are sounded as chords, especially as long-duration chords, the difference between meantone intonation and equal-tempered intonation can be quite noticeable.

Enharmonically equivalent pitches can be referred to with a single name in many situations, such as the numbers of integer notation used in serialism and musical set theory and as employed by MIDI.

Inancient Greek music the enharmonic was one of the three Greek genera in music in which the tetrachords are divided (descending) as a ditone plus two microtones. The ditone can be anywhere from 16/13to9/7 (3.55 to 4.35 semitones) and the microtones can be anything smaller than 1 semitone.[5] Some examples of enharmonic genera are

Some key signatures have an enharmonic equivalent that contains the same pitches, albeit spelled differently. In twelve-tone equal temperament, there are three pairs each of major and minor enharmonically equivalent keys: B major/C♭ major, G♯ minor/A♭ minor, F♯ major/G♭ major, D♯ minor/E♭ minor, C♯ major/D♭ major and A♯ minor/B♭ minor.

Keys that require more than 7 sharps or flats are called theoretical keys. They have enharmonically equivalent keys with simpler key signatures, so are rarely seen.

F flat major - (E major)

G sharp major - (A flat major)

D flat minor - (C sharp minor)

E sharp minor - (F minor)