The europium anomaly is the phenomenon whereby the europium (Eu) concentration in a mineral is either enriched or depleted relative to some standard, commonly a chondriteormid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB). In geochemistry a europium anomaly is said to be "positive" if the Eu concentration in the mineral is enriched relative to the other rare-earth elements (REEs), and is said to be "negative" if Eu is depleted relative to the other REEs.

While all lanthanides form relatively large trivalent (3+) ions, Eu and cerium (Ce) have additional valences, europium forms 2+ ions, and Ce forms 4+ ions, leading to chemical reaction differences in how these ions can partition versus the 3+ REEs. In the case of Eu, its reduced divalent (2+) cations are similar in size and carry the same charge as Ca2+, an ion found in plagioclase and other minerals. While Eu is an incompatible element in its trivalent form (Eu3+) in an oxidizing magma, it is preferentially incorporated into plagioclase in its divalent form (Eu2+) in a reducing magma, where it substitutes for calcium (Ca2+).[2]

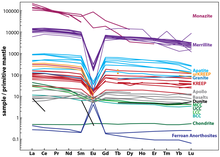

Enrichment or depletion is generally attributed to europium's tendency to be incorporated into plagioclase preferentially over other minerals. If a magma crystallizes stable plagioclase, most of the Eu will be incorporated into this mineral, causing a higher than expected concentration of Eu in the mineral versus other REE in that mineral (a positive anomaly). The rest of the magma will then be relatively depleted in Eu with a concentration of Eu lower than expected versus the concentrations of other REEs in that magma. If the Eu-depleted magma is then separated from its plagioclase crystals and subsequently solidifies, its chemical composition will display a negative Eu anomaly (because the Eu is locked up in the plagioclase left in the magma chamber). Conversely, if a magma accumulates plagioclase crystals before solidification, its rock composition will display a relatively positive Eu anomaly.[3][4]

A well-known example of the Eu anomaly is seen on the Moon. REE analyses of the Moon's light-colored lunar highlands show a large positive Eu anomaly due to the plagioclase-rich anorthosite comprising the highlands. The darker lunar mare, consisting mainly of basalt, shows a large negative Eu anomaly. This has led geologists to speculate as to the genetic relationship between the lunar highlands and mare. It is possible that much of the Moon's Eu was incorporated into the earlier, plagioclase-rich highlands, leaving the later basaltic mare strongly depleted in Eu.[5]