| Renaissance |

|---|

The School of Athens (1509–1511) by Raphael

|

| Aspects |

| Regions |

| History and study |

|

|

The German Renaissance, part of the Northern Renaissance, was a cultural and artistic movement that spread among German thinkers in the 15th and 16th centuries, which developed from the Italian Renaissance. Many areas of the arts and sciences were influenced, notably by the spread of Renaissance humanism to the various German states and principalities. There were many advances made in the fields of architecture, the arts, and the sciences. Germany produced two developments that were to dominate the 16th century all over Europe: printing and the Protestant Reformation.

One of the most important German humanists was Konrad Celtis (1459–1508). Celtis studied at Cologne and Heidelberg, and later travelled throughout Italy collecting Latin and Greek manuscripts. Heavily influenced by Tacitus, he used the Germania to introduce German history and geography. Eventually he devoted his time to poetry, in which he praised Germany in Latin. Another important figure was Johann Reuchlin (1455–1522) who studied in various places in Italy and later taught Greek. He studied the Hebrew language, aiming to purify Christianity, but encountered resistance from the church.

The most significant German Renaissance artist is Albrecht Dürer especially known for his printmakinginwoodcut and engraving, which spread all over Europe, drawings, and painted portraits. Important architecture of this period includes the Landshut Residence, Heidelberg Castle, the Augsburg Town Hall as well as the Antiquarium of the Munich Residenz in Munich, the largest Renaissance hall north of the Alps.[1][circular reference]

The Renaissance was largely driven by the renewed interest in classical learning, and was also the result of rapid economic development. At the beginning of the 16th century, Germany (referring to the lands contained within the Holy Roman Empire) was one of the most prosperous areas in Europe despite a relatively low level of urbanization compared to Italy or the Netherlands.[2][full citation needed] It benefited from the wealth of certain sectors such as metallurgy, mining, banking and textiles. More importantly, book-printing developed in Germany, and German printers dominated the new book-trade in most other countries until well into the 16th century.

The concept of the Northern Renaissance or German Renaissance is somewhat confused by the continuation of the use of elaborate Gothic ornament until well into the 16th century, even in works that are undoubtedly Renaissance in their treatment of the human figure and other respects. Classical ornament had little historical resonance in much of Germany, but in other respects Germany was very quick to follow developments, especially in adopting printing with movable type, a German invention that remained almost a German monopoly for some decades, and was first brought to most of Europe, including France and Italy, by Germans. [citation needed]

Printmakingbywoodcut and engraving was already more developed in Germany and the Low Countries than elsewhere in Europe, and the Germans took the lead in developing book illustrations, typically of a relatively low artistic standard, but seen all over Europe, with the woodblocks often being lent to printers of editions in other cities or languages. The greatest artist of the German Renaissance, Albrecht Dürer, began his career as an apprentice to a leading workshop in Nuremberg, that of Michael Wolgemut, who had largely abandoned his painting to exploit the new medium. Dürer worked on the most extravagantly illustrated book of the period, the Nuremberg Chronicle, published by his godfather Anton Koberger, Europe's largest printer-publisher at the time.[3]

After completing his apprenticeship in 1490, Dürer travelled in Germany for four years, and Italy for a few months, before establishing his own workshop in Nuremberg. He rapidly became famous all over Europe for his energetic and balanced woodcuts and engravings, while also painting. Though retaining a distinctively German style, his work shows strong Italian influence, and is often taken to represent the start of the German Renaissance in visual art, which for the next forty years replaced the Netherlands and France as the area producing the greatest innovation in Northern European art. Dürer supported Martin Luther but continued to create Madonnas and other Catholic imagery, and paint portraits of leaders on both sides of the emerging split of the Protestant Reformation.[3]

Dürer died in 1528, before it was clear that the split of the Reformation had become permanent, but his pupils of the following generation were unable to avoid taking sides. Most leading German artists became Protestants, but this deprived them of painting most religious works, previously the mainstay of artists' revenue. Martin Luther had objected to much Catholic imagery, but not to imagery itself, and Lucas Cranach the Elder, a close friend of Luther, had painted a number of "Lutheran altarpieces", mostly showing the Last Supper, some with portraits of the leading Protestant divines as the Twelve Apostles. This phase of Lutheran art was over before 1550, probably under the more fiercely aniconic influence of Calvinism, and religious works for public display virtually ceased to be produced in Protestant areas. Presumably largely because of this, the development of German art had virtually ceased by about 1550, but in the preceding decades German artists had been very fertile in developing alternative subjects to replace the gap in their order books. Cranach, apart from portraits, developed a format of thin vertical portraits of provocative nudes, given classical or Biblical titles.[4]

Lying somewhat outside these developments is Matthias Grünewald, who left very few works, but whose masterpiece, his Isenheim Altarpiece (completed 1515), has been widely regarded as the greatest German Renaissance painting since it was restored to critical attention in the 19th century. It is an intensely emotional work that continues the German Gothic tradition of unrestrained gesture and expression, using Renaissance compositional principles, but all in that most Gothic of forms, the multi-winged triptych.[5]

The Danube School is the name of a circle of artists of the first third of the 16th century in Bavaria and Austria, including Albrecht Altdorfer, Wolf Huber and Augustin Hirschvogel. With Altdorfer in the lead, the school produced the first examples of independent landscape art in the West (nearly 1,000 years after China), in both paintings and prints.[6] Their religious paintings had an expressionist style somewhat similar to Grünewald's. Dürer's pupils Hans Burgkmair and Hans Baldung Grien worked largely in prints, with Baldung developing the topical subject matter of witches in a number of enigmatic prints.[7]

Hans Holbein the Elder and his brother Sigismund Holbein painted religious works in the late Gothic style. Hans the Elder was a pioneer and leader in the transformation of German art from the Gothic to the Renaissance style. His son, Hans Holbein the Younger was an important painter of portraits and a few religious works, working mainly in England and Switzerland. Holbein's well known series of small woodcuts on the Dance of Death relate to the works of the Little Masters, a group of printmakers who specialized in very small and highly detailed engravings for bourgeois collectors, including many erotic subjects.[9]

The outstanding achievements of the first half of the 16th century were followed by several decades with a remarkable absence of noteworthy German art, other than accomplished portraits that never rival the achievement of Holbein or Dürer. The next significant German artists worked in the rather artificial style of Northern Mannerism, which they had to learn in Italy or Flanders. Hans von Aachen and the Netherlandish Bartholomeus Spranger were the leading painters at the Imperial courts in Vienna and Prague, and the productive Netherlandish Sadeler family of engravers spread out across Germany, among other counties.[10]

In Catholic parts of South Germany the Gothic tradition of wood carving continued to flourish until the end of the 18th century, adapting to changes in style through the centuries. Veit Stoss (d. 1533), Tilman Riemenschneider (d.1531) and Peter Vischer the Elder (d. 1529) were Dürer's contemporaries, and their long careers covered the transition between the Gothic and Renaissance periods, although their ornament often remained Gothic even after their compositions began to reflect Renaissance principles.[11]

Renaissance architecture in Germany was inspired first by German philosophers and artists such as Albrecht Dürer and Johannes Reuchlin who visited Italy. Important early examples of this period are especially the Landshut Residence, the CastleinHeidelberg, Johannisburg PalaceinAschaffenburg, Schloss Weilburg, the City Hall and Fugger HousesinAugsburg and St. MichaelinMunich, the largest Renaissance church north of the Alps.

A particular form of Renaissance architecture in Germany is the Weser Renaissance, with prominent examples such as the City HallofBremen and the JuleuminHelmstedt.

In July 1567 the city council of Cologne approved a design in the Renaissance style by Wilhelm Vernukken for a two storied loggia for Cologne City Hall. St MichaelinMunich is the largest Renaissance church north of the Alps. It was built by Duke William VofBavaria between 1583 and 1597 as a spiritual center for the Counter Reformation and was inspired by the Church of il Gesù in Rome. The architect is unknown. Many examples of Brick Renaissance buildings can be found in Hanseatic old towns, such as Stralsund, Wismar, Lübeck, Lüneburg, Friedrichstadt and Stade. Notable German Renaissance architects include Friedrich Sustris, Benedikt Rejt, Abraham van den Blocke, Elias Holl and Hans Krumpper.

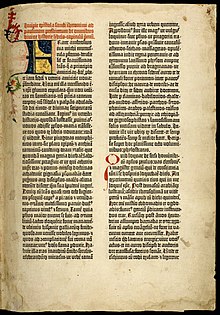

Born Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden,[12] Johannes Gutenberg is widely considered the most influential person within the German Renaissance. As a free thinker, humanist, and inventor, Gutenberg also grew up within the Renaissance, but influenced it greatly as well. His best-known invention is the printing press in 1440. Gutenberg's press allowed the humanists, reformists, and others to circulate their ideas. He is also known as the creator of the Gutenberg Bible, a crucial work that marked the start of the Gutenberg Revolution and the age of the printed book in the Western world.

Johann Reuchlin was the most important aspect of world culture teaching within Germany at this time. He was a scholar of both Greek and Hebrew. Graduating, then going on to teach at Basel, he was considered extremely intelligent. Yet after leaving Basel, he had to start copying manuscripts and apprenticing within areas of law. However, he is most known for his work within Hebrew studies. Unlike some other "thinkers" of this time, Reuchlin submerged himself into this, even creating a guide to preaching within the Hebrew faith. The book, titled De Arte Predicandi (1503), is possibly one of his best-known works from this period.

Albrecht Dürer was at the time, and remains, the most famous artist of the German Renaissance. He was famous across Europe, and greatly admired in Italy, where his work was mainly known through his prints. He successfully integrated an elaborate Northern style with Renaissance harmony and monumentality. Among his best known works are Melencolia I, the Four Horsemen from his woodcut Apocalypse series, and Knight, Death, and the Devil. Other significant artists were Lucas Cranach the Elder, the Danube School and the Little Masters.

Martin Luther[13] was a Protestant Reformer who criticized church practices such as selling indulgences, against which he published in his Ninety-Five Theses of 1517. Luther also translated the Bible into German, making the Christian scriptures more accessible to the general population and inspiring the standardization of the German language.

|

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General |

| ||||||

| By field |

| ||||||

| By region |

| ||||||

| Lists |

| ||||||

| Related |

| ||||||

|

| |

|---|---|

Ethnolinguistic groupofNorthern European origin primarily identified as speakers of Germanic languages | |

| History |

|

| Early culture |

|

| Languages |

|

| Groups |

|

| Christianization |

|

| |

| Authority control databases: National |

|

|---|