| Jantar Mantar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Jaipur, Rajasthan, India |

| Coordinates | 26°55′29″N 75°49′28″E / 26.92472°N 75.82444°E / 26.92472; 75.82444 |

| Area | 1.8652 ha (4.609 acres) |

| Built | 1728–1734; 290 years ago (1734) |

| Governing body | Government of Rajasthan |

| Official name | The Jantar Mantar, Jaipur |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iii), (iv) |

| Designated | 2010 (34th session) |

| Reference no. | 1338 |

| Region | Southern Asia |

|

Show map of Jaipur

Location in Rajasthan Show map of RajasthanLocation in India Show map of India | |

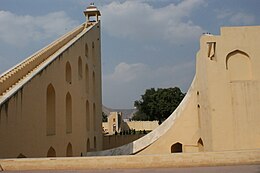

The Jantar Mantar is a collection of 19 astronomical instruments built by the Rajput king Sawai Jai Singh, the founder of Jaipur, Rajasthan. The monument was completed in 1734.[1][2] It features the world's largest stone sundial, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[1][3] It is near City Palace and Hawa Mahal.[4] The instruments allow the observation of astronomical positions with the naked eye.[1] The observatory is an example of the Ptolemaic positional astronomy which was shared by many civilizations.[1][2]

The monument features instruments operating in each of the three main classical celestial coordinate systems: the horizon-zenith local system, the equatorial system, and the ecliptic system.[2] The Kanmala Yantraprakara is one that works in two systems and allows transformation of the coordinates directly from one system to the other.[5] It has the biggest sundial in the world.

The monument was damaged in the 19th century. Early restoration work was undertaken under the supervision of Major Arthur Garrett, a keen amateur astronomer, during his appointment as Assistant State Engineer for the Jaipur District.[6]

The name jantar is derived from "yantra" a Sanskrit word, meaning "instrument, machine", and mantar from "mantrana" also a Sanskrit word meaning "consult, calculate").[7] Therefore, Jantar Mantar literally means 'calculating instrument'.[3]

Jai Singh noticed that the Zij, which was used for determining the position of celestial objects, did not match the positions calculated on the table. He constructed five new observatories in different cities in order to create a more accurate Zij. The astronomical tables Jai Singh created, known as the Zij-i Muhammad Shahi, were continuously used in India for a century. (However, the table had little significance outside of India.) Also, it was used to measure time.[8]

Exactly when Raja Jai Singh began construction in Jaipur is unknown, but several instruments had been built by 1728, and the construction of the instruments in Jaipur continued until 1738. During 1735, when construction was at its peak, at least 23 astronomers were employed in Jaipur, and due to the changing political climate, Jaipur replaced Delhi as Raja Jai Singh's main observatory and remained Jai Singh's central observatory until his death in 1743. The observatory lost support under Isvari Singh (r.1743-1750) because of a succession war between him and his brother. However, Mado Singh (r. 1750–1768), Isvari Singh's successor, supported the observatory, although it did not see the same level of activity as under Jai Singh. Although some restorations were made to the Jantar Mantar under Pratap Singh (r.1778-1803), activity at the observatory died down again. During this time, a temple was constructed and Pratap Singh turned the site of the observatory into a gun factory.[9]

Ram Singh (r. 1835–1880) completed restoring the Jantar Mantar in 1876, and even made some of the instruments more durable by inserting lead into the instruments' lines and using stone to restore some of the plaster instruments. However, the observatory soon became neglected again, and was not restored until 1901 under Madho Singh II (r. 1880–1922) [8]

The observatory consists of nineteen instruments for measuring time, predicting eclipses, tracking location of major stars as the Earth orbits around the Sun, ascertaining the declinations of planets, and determining the celestial altitudes and related ephemerides. The instruments are (alphabetical):[2]

The Vrihat Samrat Yantra, which means the "great king of instruments", is 88 feet (27 m) high, making it one of the world's largest sundials. [14] Its face is angled at 27 degrees, the latitude of Jaipur. It is purported to tell the time to an accuracy of about two seconds in Jaipur local time.[15] Its shadow moves visibly at 1 mm per second, or roughly a hand's breadth (6 cm) every minute, The Hindu chhatri (small cupola) on top is used as a platform for announcing eclipses and the arrival of monsoons.

The instruments are in most cases huge structures. The scale to which they have been built has been alleged to increase their accuracy. However, the penumbra of the sun can be as wide as 30 mm, making the 1mm increments of the Samrat Yantra sundial devoid of any practical significance. Additionally, the masons constructing the instruments had insufficient experience with construction of this scale, and subsidence of the foundations has subsequently misaligned them.[citation needed]

Built from local stone and marble, each instrument carries an astronomical scale, generally marked on the marble inner lining. Bronze tablets, bricks and mortar were also employed in building the instruments in the monument spread over about 18,700 square metres.[2] It was in continuous use until about 1800, then fell in disuse and disrepair.[2] Restored again several times during the British colonial rule, particularly in 1902, the Jantar Mantar was declared a national monument in 1948. It was restored in 2006.[2] The restoration process in early 20th century replaced some of the original materials of construction with different materials.[2]

Jantar Mantar is managed under the Archeological Sites and Monuments Act of Rajasthan since 1961, and protected as a National Monument of Rajasthan since 1968.[16]

The Vedas mention astronomical terms, measurement of time and calendar, but do not mention any astronomical instruments.[4] The earliest discussion of astronomical instruments, gnomon and clepsydra, is found in the Vedangas, ancient Sanskrit texts.[4][17] The gnomon (called Śaṅku, शङ्कु)[18] found at Jantar Mantar monument is discussed in these first millennium BCE Vedangas and in many later texts such as the Katyayana Sulbasutras.[4] Other discussions of astronomical instruments are found in Hinduism texts such as the fourth century BCE[17] Arthashastra, Buddhist texts such as Sardulakarna-avadana, and Jainism texts such as Surya-prajnapti. The theories behind the instruments are found in texts by the fifth century CE Aryabhatta, sixth century CE Brahmagupta and Varahamihira, ninth century Lalla, eleventh century Sripati and Bhaskara. The texts of Bhaskara have dedicated chapters on instruments and he calls them Yantra-adhyaya.[4][17]

The theory of chakra-yantra, yasti-yantra, dhanur-yantra, kapala-yantra, nadivalaya-yantra, kartari-yantra, and others are found in the ancient texts.[4]

The full extent of how Jai Singh's instruments were used for astronomical observation remains unclear. While the instruments themselves were impressive, there is limited evidence of a dedicated observational program or a team of trained astronomers. This raises the question of whether the observatory's primary purpose was purely scientific or also served other symbolic or cultural functions.

The Zij Muhammad-Shahi, an astronomical handbook compiled under Jai Singh's patronage, does not appear to rely heavily on data collected from his observatories. Instead, it primarily utilizes existing tables from sources like the Zij-i Ulugh Beg and Philippe de la Hire's astronomical tables. The Zij Muhammad-Shahi essentially adapts these tables by incorporating adjustments for the precession of the equinoxes and the difference in longitude between Paris and Delhi.[19]

It was used as a filming location for the 2006 film The Fall as a maze.

Storm Thorgerson photographed the sundial for the cover of Shpongle's DVD, Live at the Roundhouse 2008.[20]

It was photographed by Julio Cortázar with the collaboration of Antonio Gálvez for the book Prosa del Observatorio (Editorial Lumen: Barcelona, 1972).

{{cite book}}: |last1= has generic name (help)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

|

| |

|---|---|

| Astronomers |

|

| Works |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Concepts |

|

| Centres |

|

| Other regions |

|

| Months of the Vedic calendar |

|

|

Telescopes and Observatories in India

| |

|---|---|

| Observatories |

|

| Telescopes |

|

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|