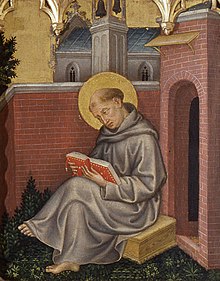

The just price is a theory of ethicsineconomics that attempts to set standards of fairness in transactions. With intellectual roots in ancient Greek philosophy, it was advanced by Thomas Aquinas based on an argument against usury, which in his time referred to the making of any rate of interestonloans. It gave rise to the contractual principle of laesio enormis.

The argument against usury was that the lender was receiving income for nothing, since nothing was actually lent, rather the money was exchanged. Furthermore, a dollar can only be fairly exchanged for a dollar, so asking for more is unfair. Aquinas later expanded his argument to oppose any unfair earnings made in trade, basing the argument on the Golden Rule. The Christian should "do unto others as you would have them do unto you", meaning he should trade value for value. Aquinas believed that it was specifically immoral to raise prices because a particular buyer had an urgent need for what was being sold and could be persuaded to pay a higher price because of local conditions:

Aquinas would therefore condemn practices such as raising the price of building supplies in the wake of a natural disaster. Increased demand caused by the destruction of existing buildings does not add to a seller's costs, so to take advantage of buyers' increased willingness to pay constituted a species of fraud in Aquinas's view.[2]

Aquinas believed all gains made in trade must relate to the labour exerted by the merchant, not to the need of the buyer. Hence, he condoned moderate gain as payment even for unnecessary trade, provided the price were regulated and kept within certain bounds:

In Aquinas' time, most products were sold by the immediate producers (i.e. farmers and craftspeople), and wage-labor and banking were still in their infancy. The role of merchants and money-lenders was limited. The later School of Salamanca argued that the just price is determined by common estimation which can be identical with the market price -depending on various circumstances such as relative bargaining power of sellers and buyers- or can be set by public authorities[citation needed]. With the rise of Capitalism, the use of just price theory faded, largely replaced by the microeconomic concept of supply and demand from Locke, Steuart, Ricardo, Ibn Taymiyyah, and especially Adam Smith. In modern economics regarding returns to the means of production, interest is seen as payment for a valuable service, which is the use of the money, though most banking systems still forbid excessive interest rates.

Likewise, during the rapid expansion of capitalism over the past several centuries the theory of the just price was used to justify popular action against merchants who raised their prices in years of dearth. The Marxist historian E. P. Thompson emphasized the continuing force of this tradition in his article on the "Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century."[3] Other historians and sociologists have uncovered the same phenomenon in variety of other situations including peasants riots in continental Europe during the nineteenth century and in many developing countries in the twentieth. The political scientist James C. Scott, for example, showed how this ideology could be used as a method of resisting authority in The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Subsistence and Rebellion in Southeast Asia.[4]

Although the Imperial Roman Code, the Corpus Juris Civilis had stated that the parties to an exchange were entitled to try to outwit one another,[5] the view developed that a contract could be unwound if it was significantly detrimental to one party: if there were abnormal harm (laesio enormis). This meant that if an agreement was significantly imbalanced to the detriment of one party, the courts would decline to enforce it, and have jurisdiction to reverse unjust enrichment. Through the 19th century, the codifications in France and Germany declined to adopt the principle while common law jurisdictions attempted to generalise the doctrine of freedom of contract. However, in practice, and increasingly over the 20th century and early 21st century, the law of consumer protection, tenancy contracts, and labour law was regulated by statute to require fairness in exchange. Certain terms would be compulsory, others would be regarded as unfair, and courts could substitute their judgment for what would be just in all the circumstances.

| Authority control databases: National |

|

|---|