Patrick Kelly

| |

|---|---|

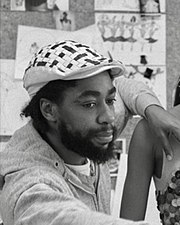

Patrick Kelly in his Paris workshop, ca. 1985

| |

| Born | (1954-09-24)September 24, 1954

Vicksburg, Mississippi, U.S.

|

| Died | January 1, 1990(1990-01-01) (aged 35) |

| Burial place | Père-Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, France |

| Occupation | Fashion designer |

| Years active | 1974–1990 |

| Known for | Patrick Kelly Paris |

| Partner | Bjorn Amelan |

Patrick Kelly (September 24, 1954 – January 1, 1990) was an American fashion designer who came to fame in France. Among his accomplishments, he was the first American to be admitted to the Chambre syndicale du prêt-à-porter des couturiers et des créateurs de mode, the prestigious governing body of the French ready-to-wear industry. Kelly's designs were noted for their exuberance, humor and references to pop culture and Black folklore.

Kelly was born on September 24, 1954, in Vicksburg, Mississippi.[1] He was raised by his mother Letha Mae Kelly and father Danie S. Kelly, a home economics teacher and cab driver, respectively. He had two siblings: Danie Kelly, Jr. and William M. Kelly. After his father's death in 1969 his grandmother assisted with his upbringing.[citation needed] His interests in fashion surfaced in high school, when he learned to sew.[2] After graduating high school in 1972, he briefly attended Mississippi's Jackson State University before moving to Atlanta, Georgia.[3]

In 1974 Atlanta, Kelly supported himself by working at an AMVETS thrift shop, where he had access to donated designer dresses and coats that he modified and sold alongside his own designs. He ultimately had his own store in the city's Buckhead district.[3] He also worked fashion shows at the Atlanta Hilton with upcoming super model Iman and established a modeling agency and clothing line under the name Longboy.[citation needed] In 1979, he connected with the pioneering Black supermodel Pat Cleveland, who admired the clothing he was making and encouraged him to move to New York City. After a lackluster year in New York, he moved to Paris in 1980, again at Cleveland's suggestion.[4] In Paris, he found more immediate success and soon developed his signature slinky, brightly colored jersey dresses adorned with colored buttons and bows in a nod to the sophisticated cut-rate style of the Southern women of his childhood.[2] Kelly met Bjorn Amelan, a photographers' representative, in 1983. The two quickly became lovers, with Amelan taking a management role in Kelly's burgeoning enterprise.[2]

Kelly began to sell his designs at the trend-setting Victoire boutiques in Paris.[5] In an interview, the store's buyer said, "Patrick landed like a bomb in my shop in 1985. He was so gay and so full of energy, and so were his clothes."[6] Also in 1985, the French edition of Elle Magazine covered Kelly with a six-page spread in its February issue.[7] During this period, he began to acquire celebrity couture clients, such as Bette Davis, Paloma Picasso, Grace Jones, Madonna, Cicely Tyson and Goldie Hawn.[8] He also participated in a notable collaboration with jewelry designer David Spada, one product of which was one of Kelly's most famous designs, a Josephine Baker-inspired ensemble with a banana skirt now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[9][10]

In 1987, the Warnaco fashion conglomerate signed an agreement to manufacture Kelly's clothing. With Warnaco's backing, Kelly designs were soon available in stores throughout the world.[2] That year, his sales approached $7 million.[11] With the support of designer Sonia Rykiel, Kelly was admitted in 1988 to the prestigious Chambre syndicale du prêt-à-porter des couturiers et des créateurs de mode. His young label thus became an official colleague of brands such as Yves Saint Laurent, Chanel and Christian Dior.[6] He was the first American to join the organization, which is the trade association for the French ready-to-wear industry. Through this affiliation, Kelly was able to present runway shows at The Louvre.[11] Describing one such 1988 show, The Christian Science Monitor commented, "Styles ranged from the sublime—tailored suits and dresses with longer hemlines, mostly in somber gray flannel, and flowing crepe pants—to the ridiculous—motorcycle-helmet hats, lopsided pockets, scoop necklines trimmed with huge gardenias, and, of course, an abundance of buttons."[6]

Kelly was an avid collector of Black memorabilia, with an affinity for items depicting racial stereotypes that many people find challenging, offensive or demeaning. He deployed this material ironically in his designs, which feature cartoonish watermelon wedges, black baby dolls, bananas and golliwogs, among other images.[8] In 2004, Robin Givhan, writing in the Washington Post, observed that an important aspect of Kelly's work as a designer was the way he foregrounded race and heritage in his designs, choices of models and public image:

Any lasting contribution that Kelly made to fashion's vocabulary is dominated by the singular significance of his ethnicity. Kelly was African-American and that fact played prominently in his designs, in the way he presented them to the public and in the way he engaged his audience. No other well-known fashion designer has been so inextricably linked to both his race and his culture. And no other designer was so purposeful in exploiting both.[12]

Kelly sought inclusiveness in the clothes he designed, telling People Magazine in 1987, "I design for fat women, skinny women, all kinds of women. My message is, you're beautiful just the way you are." At his March, 1987 show, one of his models was eight months pregnant.[4]

By 1989, Kelly was at the height of his success, producing his line for Warnaco in addition to other contracts—including one for Benetton—while developing plans for lingerie, perfume and menswear lines.[4] That August, Kelly became ill and was unable to complete preparations for his October show, which soon resulted in the cancellation of his Warnaco agreement. Kelly was sick with AIDS, but the hope of his partial recovery and business considerations kept the nature of his illness secret until after his death.[2] Kelly died on January 1, 1990, survived by Amelan and his mother.[1] At Kelly's memorial service, his friend and client Gloria Steinem concluded her remarks by saying, "Instead of dividing us with gold and jewels, he unified us with buttons and bows."[8] Kelly is buried in the 50th division of Paris's Père-Lachaise cemetery.[13]

In 2004, The Brooklyn Museum presented Patrick Kelly: A Retrospective, featuring 60 Kelly ensembles together with fashion photographs and selections from his collections of Black memorabilia, all borrowed from the Kelly estate.[8] In 2014, the Philadelphia Museum of Art mounted Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love, which celebrated the promised gift of 80 ensembles to the museum from the estate.[14]

There are two main repositories of Kelly's garments in the United States. In addition to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jackson State University, which Kelly briefly attended, maintains a collection of approximately 250 items. Jackson State exhibited part of its holdings in Patrick Kelly: From Mississippi to New York to Paris and Back in 2016.[15] The Schomburg Center of the New York Public Library holds Kelly's sketchbooks and related materials,[16] as well videos of runway shows, interviews and his memorial service.[17]

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Artists |

|

| Other |

|