Truganini

| |

|---|---|

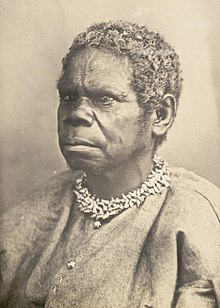

Portrait of Truganini by Charles A. Woolley

| |

| Born | c.1812 |

| Died | 8 May 1876 (aged 63–64) |

| Other names | Truganini, Trucanini, Trucaninny, Trugananner, Lydgugee and Lalla Rookh |

| Known for | Being described as the last "full-blooded" Aboriginal Tasmanian |

| Spouses | Wurati Maulboyheenner Mannapackername William Lanne |

Truganini (c.1812 – 8 May 1876), also known as Lalla Rookh and Lydgugee,[1] was a woman famous for being widely described as the last "full-blooded" Aboriginal Tasmanian to survive British colonisation. Although she was one of the last speakers of the Indigenous Tasmanian languages, Truganini was not the last Aboriginal Tasmanian.[2]

She lived through the devastation of invasion and the Black War in which most of her relatives died, avoiding death herself by being assigned as a guide in expeditions organised to capture and forcibly exile all the remaining Indigenous Tasmanians. Truganini was later taken to the Port Phillip District where she engaged in armed resistance against the colonists. She herself was then exiled, first to the Wybalenna Aboriginal EstablishmentonFlinders Island and then to Oyster Cove in southern Tasmania. Truganini died at Hobart in 1876, her skeleton later being placed on public display at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery until 1948. Her remains were finally cremated and laid to rest in 1976.[3]

In being mythologised as "the last of her people", Truganini became the tragic and triumphal symbol of the conquest of British colonists over an "inferior race".[2][4] In modern times, Truganini's life has become representative of both the dispossession and destruction that was exacted upon Indigenous Australians and also their determination to survive the colonial genocidal policies that were enforced against them.[5][2]

Other spellings of her name include Trukanini,[6] Trugernanner, Trugernena, Truganina, Trugannini, Trucanini, Trucaminni,[a] and Trucaninny.[b] Truganini was widely known by the nickname Lalla(h) Rookh,[a] and also called Lydgugee.

In the Indigenous Bruny Island language, truganina was the name of the grey saltbush, Atriplex cinerea.[8]

Truganini was born around 1812[9]atRecherche Bay (Lyleatea) in southern Tasmania.[10] Her father was Manganerer, a senior figure of the Nuenonne people whose country extended from Recherche Bay across the D'Entrecasteaux ChanneltoBruny Island (Lunawanna-alonnah). Truganini's mother was probably a Ninine woman from the area around Port Davey.[11]

At the time of Truganini's birth, the British had already begun colonising the region around Nuenonne country, severely disrupting the ability of her people to live and practise their traditional culture. The violence directed at the Nuenonne, who were regarded as helpful to the colonists, was sustained and horrific. Around 1816, a group of British sailors raided the camp of Truganini's family, stabbing her mother to death. In 1826, Truganini's older sisters Lowhenune and Magerleede were abducted by a sealer and eventually sold to other sealers on Kangaroo Island, while in 1829 her step-mother was abducted by mutinous convicts and taken to New Zealand.[11]

There is also an account that around 1828 Truganini's uncle was shot by a soldier, and that she was abducted and raped by timber-cutters. The timber-cutters also brutally murdered and drowned two Nuenonne men, one of which was Truganini's fiancé, by throwing them out of a boat and cutting off their hands with an axe as they tried to clamber back in.[12][10]

By 1828 the British had established three whaling stations on Bruny Island. A relationship existed between the whalers and Nuenonne females, where flour, sugar and tea were exchanged for sex. Truganini participated in this trade. She also was an exceptional swimmer and provided further food for her people by diving for abalone and other shellfish.[13]

In 1828, the Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen's Land, Colonel George Arthur, ordered the creation of an Aboriginal ration station on Bruny Island, which in 1829 was placed under the authority of an English builder and evangelical Christian named George Augustus Robinson.[14]

On arriving at Bruny Island, Robinson was immediately impressed by Truganini's intelligence and decided to form a close association with her to facilitate other Nuenonne to come to the Aboriginal station which he established at Missionary Bay on the west side of the island.[15] With the assistance of Truganini, Robinson initially had some success in attracting Nuenonne and Ninine people to his establishment. He even took Truganini and her cousin Dray to Hobart dressed in fine European dresses to display them to the Lieutenant-Governor as being examples of his ability to "civilise the natives".[14]

However, colonial violence and European diseases rapidly killed off most of the Indigenous people who visited the establishment, including Truganini's father Manganerer. By October 1829, only a handful of Nuenonne and Ninine had survived, and to strengthen his father-like bonds with the survivors, Robinson oversaw the partnering of the young Truganini with an important surviving Nuenonne man named Wurati.[16]

Realising that the Aboriginal station at Bruny Island was doomed, Robinson formulated a scheme to use Truganini, Wurati and a few other captured Aboriginal people such as Kikatapula and Pagerly, to guide him to the clans residing in the uncolonised western parts of Van Diemen's Land. Once contacted, Robinson would "conciliate" these clans to accept the British invasion and avoid conflict. Lieutenant-Governor Arthur approved Robinson's plan and employed him to conduct this venture which was named the "friendly mission".[14]

The mission left Bruny Island in early 1830 with Truganini playing a very important role not only as an linguistic interpreter on local Aboriginal language and culture, but also by providing much of the seafood for the group. None of the men in the expedition could swim, so Truganini also did most of the work pushing the other group members on small rafts across the various rivers they encountered.[17]

As they made their way up the west coast past Bathurst Harbour and Macquarie Harbour, the "friendly mission" made brief contacts with Ninine and Lowreenne clans. When Truganini and Wurati were sent to obtain rations at the Macquarie Harbour Penal Station on Sarah Island, Robinson was abandoned by his other guides. Alone, starving and debilitated by skin and eye infections, Robinson was saved from death by being located by Truganini and Wurati on their return from the penal colony.[18]

By June 1830, the group had reached the north west tip of Van Diemen's Land known as Cape Grim. Here they found that the Van Diemen's Land Company had appropriated a massive area of land for farmland; displacing and massacring the local Tarkiner, Pennemukeer, Pairelehoinner, Peternidic and Peerapper clans in the process. Sealers on nearby Robbins Island were also found with women kidnapped from both local clans and elsewhere in Tasmania. On meeting Truganini, the kidnapped women cried with joy as Robinson negotiated their release. However, Robinson being informed that the government were offering a £5 bounty for every native captured, now sort financial gain from his "friendly mission". He duplicitously used a Pairelehoinner youth named Tunnerminnerwait to gather some of the local people, who he shipped to Launceston to claim the bounty. Joseph Fossey, the superintendent for the Van Diemen's Land Company, meanwhile took an interest in Truganini and wanted her as an "evening companion".[19]

The expedition made its way east to Launceston where the settler population was preparing for the climax of the Black War. Called the Black Line, it was a 2,200 man strong chain of armed colonists and soldiers to sweep the settled areas looking to kill or trap any Aboriginal people they found. Robinson, Truganini and the other guides were allowed to continue their mission to the north-east, away from the direction of the Black Line.[20]

They arrived at Cape Portland in October 1830 having rescued several Indigenous women from the slavery of the local sealers, and been joined by the respected warrior Mannalargenna and his small remnant clan. They were informed of the failure of the Black Line to capture or kill many Aboriginal people and it was decided by the government to use the nearby Bass Strait Islands as a place of enforced exile for those Indigenous Tasmanians collected by Robinson.[21]

Robinson's first choice of island to confine the approximately 20 Aboriginal Tasmanians in his charge was Swan Island. This small island was exposed to powerful gales, had poor water supply and was infested with tiger snakes. Truganini was nearly bitten was one of these snakes and was also lucky to escape a large shark when diving for crayfish. However, Robinson soon took Truganini and a few other guides off this island to accompany him to Hobart where he had a meeting with the Lieutenant-Governor in early 1831. For his "friendly mission" work, Robinson was rewarded with land grants and hundreds of pounds worth of pay increases. Truganini's reward, in contrast, was a set of cotton dresses.[22]

While in Hobart, Robinson successfully negotiated a contract with the colonial authorities for him to lead further expeditions to capture all the remaining Aboriginal Tasmanians and transfer them to confinement in Bass Strait. Robinson firstly took Truganini, the other guides and around 25 Aboriginal people held in various hospitals and jails in Hobart and Launceston, and transported them to Swan Island where the others were still being held. The combined captive population swelled to over 50 and Robinson decided to move the place of exile to a former sealer's camp on Gun Carriage Island.[23]

Gun Carriage Island proved little better than Swan Island and many of the exiled Aborigines started to sicken, with several dying in the first few weeks. Truganini was able to escape this disaster though as Robinson took her, Wurati, Kikatapula, Pagerly, Mannalargenna, Woretemoeteryenner, Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner as guides to capture the remaining Aboriginal Tasmanians in the settled districts. They started off in July 1831 with the initial aim of finding the respected Tyerrernotepanner leader Eumarrah and his small clan, whom they captured in late August near the locality of Pipers Brook. They then continued on, looking to take captive the remaining members of the Oyster Bay and Big River tribes who had condensed into a single group taking refuge in the Central Highlands. Truganini and the other Indigenous guides frustrated Robinson by seeming to alert this group of their approach and it wasn't until December that they were seized. This group which included the once-feared warriors Tongerlongeter and Montpelliatta, were paraded in Hobart before being transported to Gun Carriage Island.[14]

Truganini again avoided exile to the Bass Strait Islands by being a guide for Robinson's expedition to capture the remaining Indigenous people of the west coast of Tasmania. Several other guides including Eumarrah and Kikatapula died early in the expedition, but Robinson still managed to apprehend through deceitful means most of the remaining tribespeople from the Cape Grim region. In September 1832, Truganini saved Robinson by swimming him across the Arthur River away from a group of Tarkiner people who intended to kill him.[14]

In late 1832 and early 1833, Truganini assisted in several mostly unsuccessful expeditions in the west and south-west led by the colonist Anthony Cottrell, whom Robinson had delegated authority to while he was away.[14]

In April 1833, Robinson returned to lead another expedition to seize the west coast clans, with Truganini, Wurati and others again chosen as guides. Robinson captured the remaining Ninine by taking captive the child of a prominent man named Towterer which forced the clan to surrender. By July they had captured almost all of the remaining west coast people including the Tarkiner tribe led by a man named Wyne who had attempted to kill Robinson the previous year. Truganini was employed by Robinson to push the rafts carrying people across the rivers. The water in winter was very cold and Truganini performed this arduous task almost daily for weeks. She had a seizure after a particularly demanding day of ferrying captives.[14]

Robinson deposited his prisoners at the Macquarie Harbour Penal Station to await transportation to Flinders Island where the Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment had been formed to replace the internment camp at Gun Carriage Island. The approximately 35 captives were held in terrible conditions at Macquarie Harbour, with around half dying from bacterial pneumonia and suicide within a couple of weeks. This included previously healthy young men, pregnant women and infants. Over 80% of the captured Tarkiner people perished. After shipping off the survivors to Wybalenna, Robinson returned with his guides to Hobart.[14]

Some Aboriginal people were still reported to be residing in the wilderness around Sandy Cape and the Vale of Belvoir, so in early 1834 Robinson set out again with Truganini and the other guides to find them. Before heading west, they firstly attempted to obtain two Aboriginal slaves that were in possession of John Batman at his Kingston estate along the Ben Lomond Rivulet. However, Batman, who at this stage had tertiary syphilis, refused to give them up saying they were his property.[14]

From February to April, Robinson's group located and captured twenty Tarkiner people on the west coast. This was despite Truganini and Wurati temporarily refusing to act as guides for Robinson. However, crossing the Arthur River on the return journey, Truganini again saved Robinson's life by swimming out to his raft and towing it to the bank after it was carried away by the swift current.[14]

After sending these Tarkiner off to exile at Wybalenna, Robinson left the expedition, placing his sons in charge to find the remnant Tommigener clan located near the Vale of Belvoir. For months, Truganini and the others trudged through heavy winter snow and spring rains but finally located the last eight people of this tribe in December near the Western Bluff. In February 1835, these Tommigener were shipped off to Wybalenna from Launceston, leaving Robinson to claim his rewards for removing almost in entirety the remaining Aboriginal population from mainland Tasmania.[14]

With the completion of the removal of Aborigines from mainland Tasmania, Robinson brought his Indigenous guides to his house in Hobart for a few months of respite. During this period Truganini and Wurati became celebrities and had their portraits painted by Thomas Bock and the sculptor Benjamin Law also created casts and busts of their profiles. However, in September 1835, they too were taken into exile at the Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment with the other Indigenous Tasmanians.[24]

Robinson became the superintendent at Wybalenna and began a program of Christianising the inmates. He changed their names, made them wear European clothes and attempted to prohibit their practising of Aboriginal culture and language. Illness and mortality rates were high. Although Truganini's name was changed to Lalla Rookh, she remained otherwise resistant to the enforced changes, defiantly keeping her cultural practices.[25]

In March 1836, she and eight others from Wybalenna were chosen as guides for a final expedition led by Robinson's sons to locate a last Indigenous group in north-west Tasmania that had managed to avoid Robinson's previous missions. For sixteen months, this relatively leisurely expedition provided an escape for Truganini from the death and misery of Wybalenna. They managed to locate a Tarkiner family group with four children (one of whom would later be known as William Lanne), but they refused to go to Flinders Island. By July 1837, Truganini and the other guides were taken back to Wybalenna.[14]

In 1839, Truganini, among sixteen Aboriginal Tasmanians, accompanied Robinson to the Port Phillip District in present-day Victoria.

Oral histories of Truganini report that after arriving in the new settlement of Melbourne and disengaging with Robinson, she had a child named Louisa Esmai with John Shugnow or Strugnell at Point Nepean in Victoria, but anthropologist Diane Barwick stated that historians working on a legal case for the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service disproved those claims in 1974.[26][27][c] Louisa was grandmother to Ellen Atkinson.

After about two years of living in and around Melbourne, she joined Tunnerminnerwait and three other Tasmanian Aboriginal people. The group became outlaws, robbing and shooting at settlers around Dandenong and triggering a long pursuit by the authorities. The outlaws moved on to Bass River and then Cape Paterson. There, members of the group murdered two whalers at Watson's hut. The group was captured and sent for trial for murder at Port Phillip. A gunshot wound to Truganini's head was treated by Dr Hugh Anderson of Bass River. The two men of the group were found guilty and hanged on 20 January 1842.[28]

Truganini and most[further explanation needed] of the other Tasmanian Aboriginal people were returned to Flinders Island several months later. In 1847, the few surviving Tasmanian Aboriginal people at the Flinders Island settlement, including Truganini (not all Tasmanian Aboriginal people on the island as some suggest) were moved to a settlement at Oyster Cove, south of Hobart.[29]

According to The Times newspaper, quoting a report issued by the Colonial Office, by 1861 the number of survivors at Oyster Cove was only fourteen:

...14 persons, all adults, aboriginals of Tasmania, who are the sole surviving remnant of ten tribes. Nine of these persons are women and five are men. There are among them four married couples, and four of the men and five of the women are under 45 years of age, but no children have been born to them for years. It is considered difficult to account for this... Besides these 14 persons there is a native woman who is married to a white man, and who has a son, a fine healthy-looking child...

The article, headed "Decay of Race", adds that although the survivors enjoyed generally good health and still made hunting trips to the bush during the season, after first asking "leave to go", they were now "fed, housed and clothed at public expense" and "much addicted to drinking".[30]

According to a report in The Times she later married a Tasmanian Aboriginal person, William Lanne (known as "King Billy") who died in March 1869.[a] By 1873, Truganini was the sole survivor of the Oyster Cove group, and was again moved to Hobart.

She died in May 1876 and was buried at the former Female FactoryatCascades, a suburb of Hobart. Before her death, Truganini had pleaded to colonial authorities for a respectful burial, and requested that her ashes be scattered in the D'Entrecasteaux Channel. She feared that her body would be mutilated for perverse scientific purposes as William Lanne's had been.[31]

Despite her wishes, within two years, her skeleton was exhumed by the Royal Society of Tasmania.[32] It was placed on public display in the Tasmanian Museum in 1904 where it remained until 1947.[33] Only in April 1976, approaching the centenary of her death, were Truganini's remains finally cremated and scattered according to her wishes.[34][35] In 2002, some of her hair and skin were found in the collection of the Royal College of Surgeons of England and returned to Tasmania for burial.[36]

Truganini is often incorrectly referred to as the last speaker of a Tasmanian language.[37] However, The Companion to Tasmanian History details three full-blood Tasmanian Aboriginal women, Sal, Suke and Betty, who lived on Kangaroo Island in South Australia in the late 1870s and "all three outlived Truganini". There were also Tasmanian Aboriginal people living on Flinders and Lady Barron Islands. Fanny Cochrane Smith (1834–1905) outlived Truganini by 30 years and in 1889 was officially recognised as the last Tasmanian Aboriginal person, though there was speculation that she was actually mixed-race,[38] later refuted.[citation needed] Smith recorded songs in her native language, the only audio recordings that exist of an indigenous Tasmanian language.[9][39]

According to historian Cassandra Pybus's 2020 biography, Truganini's mythical status as the "last of her people" has overshadowed the significant roles she played in Tasmanian and Victorian history during her lifetime. Pybus states that "for nearly seven decades she lived through a psychological and cultural shift more extreme than most human imaginations could conjure; she is a hugely significant figure in Australian history".[40]

Truganini Place in the Canberra suburb of Chisholm is named in her honour.[41] The suburb of Truganina in Melbourne's outer western suburbs is believed to be named after her, as she had visited the area for a short time.

In 1835 and 1836, settler Benjamin Law created a pair of busts depicting Truganini and WoorradyinHobart Town that have come under recent controversy.[42] In 2009, members of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre protested an auction of these works by Sotheby'sinMelbourne, arguing that the sculptures were racist, perpetuated false myths of Aboriginal extinction, and erased the experiences of Tasmania's remaining indigenous populations.[43] Representatives called for the busts to be returned to Tasmania and given to the Aboriginal community, and were ultimately successful in stopping the auction.[44]

Artist Edmund Joel Dicks also created a plaster bust of Truganini, which is in the collection of the National Museum of Australia.[45]

In 1997, the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, England, returned Truganini's necklace and bracelet to Tasmania.

She is probably best known for her cylinder recordings of Aboriginal songs, recorded in 1899, which are the only audio recordings of an indigenous Tasmanian language.

|

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aboriginal Tasmanians |

| ||||||||

| Tasmanian tribes |

| ||||||||

| Aboriginal history |

| ||||||||

| Tasmanian languages |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

|

Southern region of Tasmania, Australia

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Settlements |

| ||||

| Governance |

| ||||

| Mountains |

| ||||

| Protected areas, parks and reserves |

| ||||

| Rivers |

| ||||

| Harbours, bays, inlets and estuaries |

| ||||

| Coastal features |

| ||||

| Transport |

| ||||

| Landmarks |

| ||||

| Islands |

| ||||

| Books and newspapers |

| ||||

| Flora, fauna, and fishlife |

| ||||

| Bioregions |

| ||||

| Indigenous heritage |

| ||||

| Other |

| ||||

| |||||

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| People |

|