Awaste book was one of the books traditionally used in bookkeeping. It consisted of a daily diary of all transactions in chronological order.[1] It differs from a daybook in that only a single waste book is kept, rather than a separate daybook for each of several categories. The waste book was intended for temporary use only; the information needed to be transcribed into a journal in order to begin to balance one's accounts.[2] The name of the book derives from the fact that, once its information was transferred to the journal, the waste book was unneeded.[3]

The use of the waste book has declined with the advent of double-entry accounting.

Waste books were also used in the tradition of the commonplace book and note-taking. A well known example is Isaac Newton's Waste Book in which he did much of the development of the calculus.[4] Another example is that of Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, who called his waste books sudelbücher, and which were known to have influenced Leo Tolstoy, Albert Einstein, Andre Breton, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Ludwig Wittgenstein.[5][6]

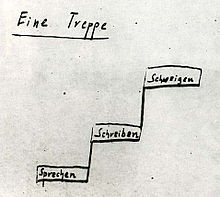

Merchants and traders have a waste book (Sudelbuch, Klitterbuch in German I believe) in which they enter daily everything they purchase and sell, messily, without order. From this, it is transferred to their journal, where everything appears more systematic, and finally to a ledger, in double entry after the Italian manner of bookkeeping, where one settles accounts with each man, once as debtor and then as creditor. This deserves to be imitated by scholars. First it should be entered in a book in which I record everything as I see it or as it is given to me in my thoughts; then it may be entered in another book in which the material is more separated and ordered, and the ledger might then contain, in an ordered expression, the connections and explanations of the material that flow from it. [46] —Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, Waste Book E, #46, 1775–1776[7]

In a general sense Cicero contrasted the short-lived memoranda of the merchant with the more carefully kept account book designed as a permanent record.[8]

Francis Bacon compared one of his notebooks to a merchant’s waste book.[9]

Francesco Sacchini recommended the use of two notebooks: “Not unlike attentive merchants... [who] keep two books, one small, the other large: the first you would call adversaria or a daybook (ephemerides), the second an account book (calendarium) and ledger (codex).”[10][11]

waste book+bookkeeping.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)