薬物源としての自然

表示

詳細は「en:Bioprospecting」を参照

従来、多くの医薬品や生物活性を持つ化学物質は、生物が生存のために他の生物の活性に影響を与えるように作り出す化学物質を研究して発見してきた[1]。

コンビナトリアルケミストリーがリード発見プロセスに不可欠な要素として台頭してきているにもかかわらず、天然物が創薬の出発材料として大きな役割を果たしていることに変わりはない[2]。2007年の報告書によると[3]、1981年から2006年の間に開発された974の低分子新規化学物質のうち、63%が天然物由来または天然物の半合成誘導体 (英語版) であった。抗菌剤、抗悪性腫瘍剤、降圧剤、抗炎症剤などの特定の治療分野では、さらに大きな数値であった[要出典]。多くの場合、これらの製品は長年にわたり伝統的に使用されてきたものである[要出典]。

天然物は、抗菌療法の現代的な技術開発のための新しい化学構造の有用な源となる可能性がある[4]。

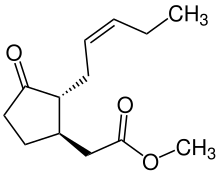

ジャスモン酸メチル (JA) の化学構造

ジャスモン酸は、傷害や細胞内シグナルへの応答に重要な役割を果たしている。それらはプロテアーゼ阻害剤[13] を介してアポトーシス[13][14] やタンパク質カスケードを誘導し、防御機能を持ち[15]、さまざまな生物学的・環境的ストレス (英語版) に対する植物の応答を調節する[15][16]。ジャスモン酸はまた、代謝産物の放出を介して膜脱分極を誘導し、ミトコンドリア膜に直接作用する能力を持っている[17]。

ジャスモン酸誘導体 (JAD) は、植物細胞の創傷反応や組織再生にも重要な役割を果たしている。また、ヒトの表皮層にもアンチエイジング効果があることが確認されている[18]。それは、細胞外マトリックス (ECM) の必須成分であるプロテオグリカン (PG) やグリコサミノグリカン (GAG) 多糖類と相互作用し、ECMの再構築を助けるものと思われている[19]。皮膚の修復に関する JADの発見は、これらの植物ホルモンの治療薬としての応用における効果に新たな関心をもたらした[18]。

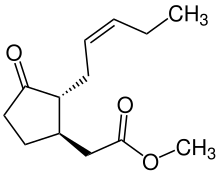

アセチルサリチル酸の化学構造。一般的にアスピリンとして知られてい る。

植物ホルモンであるサリチル酸 (SA) は、最初は柳の樹皮に由来し、それ以来、多くの種で同定されてきた。その役割は科学者によってまだ完全には解明されていないが、植物免疫 (英語版) の重要なプレーヤーを担っている[20]。また植物や動物の組織における病気や免疫応答に関与しており、複数の動物組織に影響を与えることが示されているサリチル酸結合タンパク質 (SABP) を持っている[20]。単離された化合物の最初に発見された薬効は、痛みや熱の管理に関与していた。それらはまた、細胞増殖の抑制にも積極的な役割を果たしている[13]。リンパ芽球性白血病や他のヒトの癌細胞において死を誘導する能力を持っている[13]。サリチル酸塩に由来するの最も一般的な薬物の一つは、アセチルサリチル酸としても知られるアスピリンで、抗炎症作用や解熱作用を有している[20][21]。

植物由来

詳細は﹁薬用植物﹂を参照 植物が産生する多くの二次代謝産物は、治療薬としての潜在的な薬効成分を持っている。これらの二次代謝産物は、タンパク質 (受容体、酵素など) に結合し、その機能を修飾する。そのため、植物由来の天然物は、創薬の出発点としてしばしば利用されてきた[5][6][7][8]。歴史

詳細は﹁薬学史﹂を参照 ルネサンス期までは、西洋医学における薬物の大部分は植物由来の抽出物であった[9]。その結果、創薬のための出発物質の重要な供給源としての植物種の可能性についての情報が蓄積されてきた[10]。 植物のさまざまな解剖学的部分 (例えば、根、葉、花) で産生されるさまざまな代謝産物およびホルモンに関する植物学的知識は、生理活性および薬理学的な植物特性を正しく識別するために極めて重要である[10][11]。新薬を特定し、市場での承認を得ることは、国の薬事規制当局 (英語版) によって設定された規制により、厳しいプロセスであることが証明されている[12]。ジャスモン酸

サリチル酸塩

微生物の代謝物

微生物は、生活空間や養分をめぐって互いに競争している。これらの条件で生き残るために、多くの微生物は競合する種の増殖を防ぐ能力を発達させてきた。微生物は抗菌薬の主な供給源である。ストレプトマイセス分離株 (英語版) は、貴重な抗生物質の供給源であり、薬用カビと呼ばれている。他の微生物に対する防御機構として発見された抗生物質の古典的な例は、1928年にペニシリウム真菌に汚染された細菌培養物中のペニシリンである[要出典]。海洋無脊椎動物

詳細は Sponge isolates を参照 海洋環境は、新たな生理活性物質の源となる可能性を秘めている[22]。1950年代に海洋無脊椎動物から発見されたアラビノースヌクレオシドは、リボースとデオキシリボース以外の糖鎖から生理活性ヌクレオシド構造が得られることを初めて実証した。海洋由来の最初の医薬品が承認されたとき、2004年までかかった[要出典][疑問点]。例えば、プリアルトとしても知られているイモガイの毒素ジコノチドは、重度の神経障害性疼痛を治療する。他にもいくつかの海洋由来の薬剤が、がん、抗炎症剤の使用、疼痛などの適応症を対象に臨床試験を行っている。これらの薬剤の一つにブリオスタチン様化合物があり、抗がん剤として研究が進められている[要出典]。化学的多様性

上記のように、コンビナトリアル・ケミストリーは、ハイスループットスクリーニングのニーズに対応した大規模なスクリーニングライブラリーを効率的に生成することを可能にする重要な技術であった。しかし、現在、コンビナトリアル・ケミストリーの20年の歴史を経て、化学合成が効率化したにもかかわらず、リードや薬物候補の増加には至っていないことが指摘されている[3]。そのため、コンビナトリアル・ケミストリー製品の化学的特性を、既存の医薬品や天然物と比較して分析することが求められている。それらの物理化学的特性に基づいて化学空間における化合物の分布として描かれるケモインフォマティクスの概念﹁化学的多様性﹂(chemical diversity) は、コンビナトリアル・ケミストリー・ライブラリー化合物と天然物との違いを説明するためにしばしば用いられている。合成コンビナトリアル・ライブラリーの化合物は、限られた非常に均一な化学空間しかカバーしていないように見えるが、既存の薬物、特に天然物は化学的多様性が大きく、化学空間により均等に分布している[2]。天然物とコンビナトリアル・ケミストリー・ライブラリーの化合物の間の最も顕著な違いは、キラル中心の数 (天然化合物の方がはるかに多い)、構造剛性 (天然化合物の方が高い)、および芳香族部位の数 (コンビナトリアル・ケミストリー・ライブラリーの方が高い) である。これら2つのグループ間の他の化学的な違いは、ヘテロ原子の性質 (天然物ではOとNに富み、合成化合物ではSとハロゲン原子が多く存在する)、非芳香族性不飽和度 (天然物では高い) などである。構造の剛性とキラリティーの両方が、化合物の特異性と薬剤としての有効性を高めることが知られている医薬品化学において確立された要因であることから、天然物は潜在的なリード分子として、今日のコンビナトリアル・ケミストリー・ライブラリーに匹敵することが示唆されている。スクリーニング

天然資源から新規生理活性化学物質を発見するためには、主に2つのアプローチが存在する。 第一のアプローチは、ランダム収集とマテリアルスクリーニングと呼ばれることもあるが、その収集はランダムとは程遠い。生物学的 (多くの場合、植物学的) 知識は、将来有望なファミリーを特定するためにしばしば使用される。このアプローチは、これまでに地球上の生物多様性のごく一部しか薬効が確認されていないため、効果的である。また、種が豊富な環境で生息する生物は、生き残るために防御機構や競争機構を進化させる必要がある。これらの機構は、有益な医薬品の開発に利用される可能性がある。 豊かな生態系から植物、動物、微生物のサンプルを収集することで、医薬品開発のプロセスで活用する価値のある新しい生物学的活性を生み出す可能性がある。この戦略の成功例の一つは、1960年代に始まった米国国立がん研究所による抗腫瘍剤のスクリーニングである。パクリタキセルは太平洋イチイの木、Taxus brevifolia (英語版) から同定された。パクリタキセルは、これまで知られていなかった機構 (微小管の安定化) によって抗腫瘍活性を示し、現在では肺癌、乳癌、卵巣癌、カポジ肉腫の治療薬として臨床使用が承認されている。21世紀に入ってからは、タキソールの親戚であるカバジタキセル (フランスのサノフィ社製) が前立腺がんに効果的であることが示されている。その他の例としては、次のとおりである。1. Camptotheca (Camptothecin · Topotecan · Irinotecan · Rubitecan · Belotecan); 2. Podophyllum (Etoposide · Teniposide); 3a. Anthracyclines (Aclarubicin · Daunorubicin · Doxorubicin · Epirubicin · Idarubicin · Amrubicin · Pirarubicin · Valrubicin · Zorubicin); 3b. Anthracenediones (Mitoxantrone · Pixantrone). 第二の主要なアプローチは、社会における植物の一般的な使用の研究である民族植物学と、特に薬用に焦点を当てた民族植物学の領域である伝統医学 (英語版) とを含む。 アルテミシニンは、紀元前200年から漢方薬として使用されてきたヨモギ由来の植物であるクソニンジン(Artemisia annua (英語版) )から抽出した抗マラリア薬で、多剤耐性熱帯熱マラリア原虫の併用療法 (英語版) の一つとして使用されている。構造解明

化学構造の解明は、その構造や化学活性が既にわかっている薬剤の再発見を避けるために重要である。質量分析は、イオン化後に個々の化合物を質量/電荷比に基づいて同定する方法である。化学物質は、自然界には混合物として存在しているため、個々の化学物質を分離するために液体クロマトグラフィーと質量分析 (LC-MS) を組み合わせて使用することがよくある。既知の化合物の質量スペクトルのデータベースが利用可能であり、未知の質量スペクトルに構造を割り当てるために使用できる。核磁気共鳴分光法 (NMR) は、天然物の化学構造を決定するための主要な手法である。NMRは構造中の個々の水素原子と炭素原子に関する情報を提供し、分子の構造の詳細な再構成を可能にする。脚注

- ^ Roger, Manuel Joaquín Reigosa; Reigosa, Manuel J.; Pedrol, Nuria; González, Luís (2006), Allelopathy: a physiological process with ecological implications, Springer, pp. 1, ISBN 978-1-4020-4279-9

- ^ a b “Property distributions: differences between drugs, natural products, and molecules from combinatorial chemistry”. Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences 43 (1): 218–27. (2003). doi:10.1021/ci0200467. PMID 12546556.

- ^ a b “Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years”. Journal of Natural Products 70 (3): 461–77. (March 2007). doi:10.1021/np068054v. PMID 17309302.

- ^ “Antibacterial natural products in medicinal chemistry--exodus or revival?”. Angewandte Chemie 45 (31): 5072–129. (August 2006). doi:10.1002/anie.200600350. PMID 16881035. "The handling of natural products is cumbersome, requiring nonstandardized workflows and extended timelines. Revisiting natural products with modern chemistry and target-finding tools from biology (reversed genomics) is one option for their revival."

- ^ “Drug discovery and natural products: end of an era or an endless frontier?”. Science 325 (5937): 161–5. (July 2009). doi:10.1126/science.1168243. PMID 19589993. "With the current framework of HTS in major pharmaceutical industries and increasing government restrictions on drug approvals, it is possible that the number of new natural product–derived drugs could go to zero. However, this is likely to be temporary, as the potential for new discoveries in the longer term is enormous."

- ^ “The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era”. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 14 (2): 111–29. (2015). doi:10.1038/nrd4510. hdl:10072/141449. PMID 25614221. "Here, we review strategies for natural product screening that harness the recent technical advances that have reduced [technical barriers to screening natural products in high-throughput assays]. The growing appreciation of functional assays and phenotypic screens may further contribute to a revival of interest in natural products for drug discovery."

- ^ “Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs from 1981 to 2014”. Journal of Natural Products 79 (3): 629–61. (2016). doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. PMID 26852623. "... the utilization of natural products and/or their novel structures, in order to discover and develop the final drug entity, is still alive and well. For example, in the area of cancer, over the time frame from around the 1940s to the end of 2014, of the 175 small molecules approved, 131, or 75%, are other than "S" (synthetic), with 85, or 49%, actually being either natural products or directly derived therefrom."

- ^ “The Pharmaceutical Industry in 2016. An Analysis of FDA Drug Approvals from a Perspective of the Molecule Type”. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 22 (3): 368. (2017). doi:10.3390/molecules22030368. PMC 6155368. PMID 28264468. "The outputs from 2016 indicate the so-called small molecules are losing ground against biologics, biomolecules, and other molecules inspired [by] natural products"

- ^ Sutton, David (2007). “Pedanios Dioscorides: Recording the Medicinal Uses of Plants”. In Huxley, Robert. The Great Naturalists. London: Thames & Hudson, with the Natural History Museum. pp. 32–37. ISBN 978-0-500-25139-3

- ^ a b “The worldwide trend of using botanical drugs and strategies for developing global drugs”. BMB Reports 50 (3): 111–116. (March 2017). doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2017.50.3.221. PMC 5422022. PMID 27998396.

- ^ “Modes of Action of Herbal Medicines and Plant Secondary Metabolites”. Medicines 2 (3): 251–286. (September 2015). doi:10.3390/medicines2030251. PMC 5456217. PMID 28930211.

- ^ “New scale-down methodology from commercial to lab scale to optimize plant-derived soft gel capsule formulations on a commercial scale”. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 535 (1–2): 371–378. (January 2018). doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.11.029. PMID 29154803.

- ^ a b c d “Plant stress hormones suppress the proliferation and induce apoptosis in human cancer cells” (英語). Leukemia 16 (4): 608–16. (April 2002). doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2402419. PMID 11960340.

- ^ “Methyl jasmonate and its potential in cancer therapy”. Plant Signaling & Behavior 10 (9): e1062199. (2015-07-24). doi:10.1080/15592324.2015.1062199. PMC 4883903. PMID 26208889.

- ^ a b “The jasmonate signal pathway”. The Plant Cell 14 Suppl (Suppl): S153–64. (2002). doi:10.1105/tpc.000679. PMC 151253. PMID 12045275.

- ^ “Jasmonates: Multifunctional Roles in Stress Tolerance” (English). Frontiers in Plant Science 7: 813. (2016). doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.00813. PMC 4908892. PMID 27379115.

- ^ “Jasmonates: novel anticancer agents acting directly and selectively on human cancer cell mitochondria”. Cancer Research 65 (5): 1984–93. (March 2005). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3091. PMID 15753398.

- ^ a b “The anti-ageing potential of a new jasmonic acid derivative (LR2412): in vitro evaluation using reconstructed epidermis Episkin™”. Experimental Dermatology 21 (5): 398–400. (May 2012). doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2012.01480.x. PMID 22509841.

- ^ “A jasmonic acid derivative improves skin healing and induces changes in proteoglycan expression and glycosaminoglycan structure”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 1861 (9): 2250–2260. (September 2017). doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.06.006. PMID 28602514.

- ^ a b c “Multiple Targets of Salicylic Acid and Its Derivatives in Plants and Animals”. Frontiers in Immunology 7: 206. (2016-05-26). doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00206. PMC 4880560. PMID 27303403.

- ^ “Salicylic Acid and its Derivatives in Plants: Medicines, Metabolites and Messenger Molecules”. Advances in Botanical Research. 20. (1994). pp. 163–235. doi:10.1016/S0065-2296(08)60217-7. ISBN 978-0-12-809447-1

- ^ “Investigations of the marine flora and fauna of the Islands of Palau”. Natural Product Reports 21 (1): 50–76. (February 2004). doi:10.1039/b300664f. PMID 15039835.