Jingnan campaign

| Jingnan campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

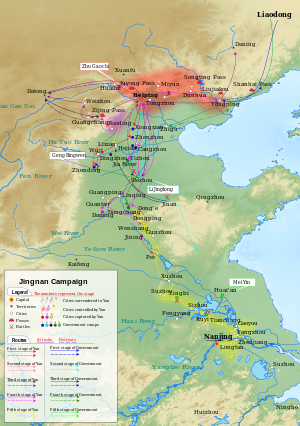

Map of Jingnan campaign | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Princedom of Yan Princedom of Ning | Ming central government | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Zhu Di, Prince of Yan Zhu Gaochi, Hereditary Prince of Yan Zhu Gaoxu, Prince of Gaoyang Comm. Yao Guangxiao Qiu Fu Zhu Neng Zhang Yu † Zhang Fu Zheng He Zhu Quan, Prince of Ning Three Guards of Doyan |

Zhu Yunwen, the Jianwen Emperor (MIA) Geng Bingwen Tie Xuan Li Jinglong Xu Huizu Qi Tai Huang Zicheng Fang Xiaoru Sheng Yong | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 120,000 | 500,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Heavy | ||||||

| Jingnan campaign | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 靖難之役 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Pacification (靖) of crisis (難) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Jingnan campaign, or Jingnan rebellion, was a three-year civil war from 1399 to 1402 in the early years of the Ming dynasty of China. It occurred between two descendants of the Ming dynasty's founder Zhu Yuanzhang: his grandson Zhu Yunwen by his first son, and Zhu Yuanzhang's fourth son Zhu Di, Prince of Yan. Though Zhu Yunwen had been the chosen crown prince of Zhu Yuanzhang and been made emperor upon the death of his grandfather in 1398, friction began immediately after Yuanzhang's death. Zhu Yunwen began arresting Zhu Yuanzhang's other sons immediately, seeking to decrease their threat. But within a year open military conflict began, and the war continued until the forces of the Prince of Yan captured the imperial capital Nanjing. The fall of Nanjing was followed by the demise of the Jianwen Emperor, Zhu Yunwen. Zhu Di was then crowned the Ming Dynasty's third emperor, the Yongle Emperor.[2]

Background[edit]

After establishing the Ming Dynasty in 1368, Zhu Yuanzhang (1328–1398), otherwise known as the Hongwu Emperor, began to consolidate the authority of the royal court. He assigned territories to the members of the royal family and stationed them across the empire. He had 26 sons, and of those who survived to adulthood, these princes were often assigned considerable land and forces. These members of the royal family did not have the administrative power over their territory, but they were entitled to a personal army that ranged from 3,000 to 19,000 men.[3] Royal members that were stationed in the northern frontier were entitled to even larger forces. For instance, Zhu Yuanzhang's 17th son Zhu Quan, Prince of Ning, was said to have had an army of over 80,000 men.[4]

The original crown prince, Yuanzhang's first son Zhu Biao, died before Yuanzhang at the age of 36 in 1392. Instead of declaring another of his sons as crown prince, Yuanzhang then declared Biao's surviving eldest teenaged son Zhu Yunwen (1377–1402) as the new heir to the throne. Zhu Yunwen was thus the nephew of Yuanzhang's other sons the feudal princes and felt threatened by their military power.

Prelude[edit]

In May 1398, when his grandfather Zhu Yuanzhang died, Zhu Yunwen ascended to the throne and was named the Jianwen Emperor. He immediately issued an order that his uncles should remain in their respective territories, and then with the assistance of his close associates Qi Tai and Huang Zicheng, made plans to demand the reduction of the military power of these perceived rivals.[5][6] The first to be considered was Zhu Yuanzhang's fourth son Zhu Di, Prince of Yan, since he had the largest territory, but the proposal was declined.[7]

Soon after, in July 1398, the Jianwen Emperor arrested his fifth uncle Zhu Su, Prince of Zhou in Kaifeng, on treason charges. The prince and his family members were stripped of royal status and exiled to Yunnan.[8] In April 1399, three more of Zhu Yuanzhang's sons, the princes of Qi, Dai, and Xiang, and their family members were stripped of their royal status. The princes of Qi and Dai were placed under house arrest in Nanjing and Datong, respectively, while the Prince of Xiang committed suicide.[9] Two months later another son, the Prince of Min, also lost his royal status and was exiled to Fujian.[10] As the rift between the regional princes and their emperor nephew grew, the Prince of Yan, who was the eldest surviving uncle of the emperor, and commanded the most powerful military, effectively assumed the leadership role among the uncles.

Initial stage, 1399[edit]

Attack on Beiping[edit]

In December 1398, to prevent what he believed was a potential attack from his uncle, the Prince of Yan, the Jianwen Emperor had appointed several imperial staff to Beiping (present day Beijing) where Zhu Di was stationed. In response, Zhu Di pretended to be ill while preparing for the anticipated war. However, the conspiracy was reported to the imperial staff in Beiping by one of the staff in Yan court.[11] As a result, the arrest for the Prince of Yan was ordered by the imperial court. Zhang Xin, one of the imperial staff, decided to leak the imperial order to the Prince of Yan.[12] To prepare for the imminent arrest, Zhu Di ordered his general Zhang Yu to gather 800 men to patrol the Yan residence in Beiping.[13]

In July, the imperial staff surrounded the Yan residence, and Zhu Di responded by executing the imperial staff and then storming the gates of Beiping.[14] By nightfall, Zhu Di was in control of the city and had officially rebelled against the imperial court.[15][16] For the next several days, the Yan forces captured Tongzhou, Jizhou, Dunhua and Miyun. By the end of July, Juyong Pass, Huailai and Yongping all fell to the Yan forces and the entire Beiping area was effectively under Yan control.[17]

As the Yan forces captured Huailai, the Prince of Gu fled to Nanjing from his territory in Xuanfu, which was situated near the Yan forces.[18] In August, an imperial order demanded that the Princes of Liao and Ning return to Nanjing. The Prince of Liao accepted the order while the Prince of Ning rejected it.[19][20] The Prince of Dai intended to support the Yan forces, but was forced to remain under house arrest in Datong.[21]

Government response, 1399–1400[edit]

First offensive[edit]

In July 1399, news of the rebellion had arrived in Nanjing. The Jianwen Emperor ordered the removal of royal status from the Prince of Yan and began to assemble an attack on Yan forces.[22][23] A headquarters for the expedition was set up in Zhending, Hebei province.[24]

Since many of the generals in the Ming court had either died or been purged by the Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang, the lack of experienced military commanders was a major concern.[25] With no other options, the 65-year-old Geng Bingwen was appointed as the commander and led 130,000 government forces north on an expedition against the Yan forces.[26] On 13 August, the government forces arrived in Zhending.[27] To prepare for the offensive, the forces were divided and stationed in Hejian, Zhengzhou and Xiongxian separately. However, on 15 August 1399, the Yan forces assaulted Xiongxian and Zhengzhou by surprise and captured both of the cities also annexing their forces.[28]

One of the generals in Geng Bingwen's camp surrendered to Zhu Di and informed him of the positions of Geng Bingwen forces. Zhu Di instructed the general to return the message that the Yan forces were approaching soon, to convince Geng Bingwen to gather his forces together to prepare for the general attack.[29]

On 24 August 1399, the Yan forces arrived in Wujixian. Based on the information gathered from the locals and the surrendered troops, they began to prepare to raid the government forces.[30]

The Yan forces launched a surprise raid on Geng Bingwen the next day, and a full-scale battle ensued. Zhu Di personally led a strike force against the flank of government forces, and Geng Bingwen suffered a crushing defeat as a result. Over 3,000 men surrendered to the Yan forces, and the remainder of the government forces fled back to Zhending. General Gu Cheng surrendered to Zhu Di.[31][32] For the next several days, the Yan forces attempted to capture Zhending but were unable to succeed. On 29 August 1399, the Yan forces withdrew back to Beiping.[33] Gu Cheng was sent back to Beiping to assist Zhu Gaochi with the defense of the city.[34]

Second offensive[edit]

As the news of Geng Bingwen's defeat reached back to Nanjing, the Jianwen Emperor became increasingly concerned about the war. Li Jinglong was proposed by Huang Zicheng as the new commander, and the proposal was accepted despite opposition from Qi Tai.[35] On 30 August 1399, Li Jinglong led a total of 500,000 men and advanced to Hejian.[1] As the news reached the Yan camp, Zhu Di was certain of a Yan victory by outlining the weaknesses of Li Jinglong.[36][37]

Defense of Beiping[edit]

On 1 September 1399, government forces from Liaodong began to lay siege to the city of Yongping.[38] Zhu Di led the Yan forces to reinforce the city on 19 September and defeated the Liaodong forces by 25 September. Following the victory, Zhu Di decided to raid the city of Daning controlled by Prince of Ning in order to annex his army.[39] The Yan forces reached Daning on 6 October, and Zhu Di went inside the city.[40] He was able to coerce the Prince of Ning and the troops in Daning to submit to him, and the strength of the Yan forces increased significantly.[41]

Upon learning that Zhu Di was away in Daning, the government forces led by Li Jinglong crossed Lugou Bridge and began to attack Beiping. However, Zhu Gaochi was able to hold off the attacks.[42] On one occasion, the government forces almost broke into the city, but the attack was held back by a suspicious Li Jinglong.[43] The temperature in Beiping is sub-zero during the month of October, and the Yan defenders poured water on the city walls at nightfall. As the walls were covered in ice the next day, the government forces were prevented from scaling the walls.[44] The government forces were composed of soldiers from the south, and they were unable to sustain their attack in the cold weather.[45]

Battle of Zhengcunba[edit]

On 19 October 1399, the Yan forces gathered in Huizhou and began its march back to Beiping.[46] By 5 November, the Yan forces were in the outskirts of Beiping and defeated the scout forces of Li Jinglong.[47] The main army of each side engaged in Zhengcunba for a major battle in the same day, and the forces of Li Jinglong suffered a crushing defeat.[48][49] At nightfall, Li Jinglong retreated from Zhengcunba hastily, and the remaining attack force in Beiping was subsequently surrounded and defeated by the Yan forces.[50][51]

The Battle of Zhengcunba was concluded by the retreat of Li Jinglong back to Dezhou.[52] The government forces lost more than 100,000 men in this battle.[53] On 9 November 1399, Zhu Di returned to Beiping and wrote to the imperial court about his intention to remove Qi Tai and Huang Zicheng from their post. Jianwen Emperor declined to respond.[54] In December, Wu Gao was dismissed from his post in Liaodong by the imperial court, and Zhu Di decided to attack Datong.[55] The Yan forces reached Guangchang on 24 December, and the garrison surrendered.[56] On 1 January 1400, the Yan forces reached Weizhou and met with no resistance yet again.[57] On 2 February, the Yan forces reached Datong and began its siege on the city. The strategic importance of Datong was significant to the imperial court, and Li Jinglong was forced to reinforce the city in a hurried manner. However, Zhu Di returned to Beiping before the government forces could arrive, and the government forces suffered a considerable number of non-combat casualties.[58] With his troops exhausted, Jinglong wrote to Zhu Di and requested an armistice.[59] During the attack in Datong, several forces from Mongolia surrendered to the Yan forces.[60] In February, the garrison at Baoding also surrendered.[61]

Battle of Baigou River[edit]

In April, Li Jinglong mobilized 600,000 men and began advancing northwards toward the Baigou River. On 24 April 1400, the Yan forces engaged with the government forces in a decisive battle.[62] The government forces ambushed Zhu Di, and the Yan forces suffered a series of defeats initially. Landmines were placed in the retreat path of the Yan forces by the government forces, which inflicted heavy losses on the Yan army on their way back to the camp.[63][64] A new battle ensued the following day, and the government forces were successful in attacking the rear of the Yan forces.[65] Zhu Di led a personal charge against the main force of Li Jinglong, and the battle turned into a stalemate as Zhu Gaochi arrived with reinforcements.[66][67] At this point, the wind started to blow and snapped the flag of Li Jinglong in half, which led to chaos in the government camp. Zhu Di seized the opportunity and launched a general assault and defeated the government forces.[68] More than 100,000 government troops surrendered to the Yan forces, and Li Jinglong retreated back to Dezhou once again.[69][70][71]

On 27 April, the Yan forces began marching toward Dezhou to lay siege to the city. The Yan forces captured Dezhou on 9 May 1400, and Li Jinglong was forced to flee to Jinan. The Yan forces followed up immediately and encircled the city of Jinan on 15 May, and Li Jinglong fled back to Nanjing.[72] Despite losing the entire army and being condemned by the imperial court, Li Jinglong was spared execution.[73]

Stalemate, 1400–1401[edit]

Battle of Jinan[edit]

As the city of Jinan was under siege by the Yan forces, the defenders led by Tie Xuan and Sheng Yong refused to surrender.[74] On 17 May 1400, the Yan forces diverted the river to flood the city.[75] Tie Xuan pretended to surrender and lured Zhu Di to the city gate.[76] As Zhu Di approached the city gate, he was ambushed by the government forces and fled back to the camp. The siege continued for the next three months.[77] The strategic importance of Jinan was crucial, and Zhu Di was determined to capture the city. After suffering several setbacks during the siege, Zhu Di turned to the use of cannons. In response, the defenders resorted to placing several plaques written with the name of Zhu Yuanzhang, father of Zhu Di, on top of the city walls. Zhu Di was forced to stop the bombardment.[78]

In June, Jianwen Emperor dispatched an envoy to negotiate for peace, but it was rejected by Zhu Di.[79] The government reinforcements arrived in Hejian around July, and disrupted the supply line of the Yan forces.[80] With the supply line threatened, Zhu Di was forced to withdraw back to Beiping on 16 August. The garrison in Jinan followed up and recaptured the city of Dezhou.[81] Both Tie Xuan and Sheng Yong were promoted to replace the commanding post previously led by Li Jinglong. The government forces advanced back north and settled in Dingzhou and Cangzhou.[82]

Battle of Dongchang[edit]

In October, Zhu Di was informed that the government forces were marching northwards, and decided to launch a pre-emptive strike on Cangzhou. Departing from Tongzhou on 25 October, the Yan forces reached Cangzhou by 27 October 1400 and captured the city in two days.[83][84] The Yan forces crossed the river and arrived in Dezhou on 4 November.[85] Zhu Di attempted to summon Sheng Yong to surrender, but was refused. Sheng Yong was defeated while leading an attack on the rear of the Yan Army.[86] In November, the Yan forces arrived in Linqing, and Zhu Di decided to disrupt the government supply line to force Sheng Yong to abandon Jinan.[87] To counter this, Sheng Yong planned for a decisive battle in Dongchang, and armed his troops with gunpowder weapons and poisonous crossbows.[88]

On 25 December 1400, the Yan forces arrived in Dongchang.[89] Sheng Yong successfully lured Zhu Di into his encirclement, in which the Yan general Zhang Yu was killed in action while trying to break Zhu Di out.[90] While Zhu Di was able to flee from the battlefield, the Yan forces suffered another defeat the next day and were forced to withdraw.[91] On 16 January 1401, the Yan forces returned to Beiping.[92] The Battle of Dongchang was the largest defeat suffered by Zhu Di since the onset of the campaign, and he was particularly saddened by the death of Zhang Yu.[93][94] During the battle, Zhu Di was almost killed on numerous occasions. However, the government forces were instructed by Jianwen Emperor to refrain from killing Zhu Di, which the Prince of Yan took advantage of.[95]

News of the victory following the Battle of Dongchang was well received by Jianwen Emperor. In January 1401, Qi Tai and Huang Zicheng were restored to their posts, and the emperor went on to worship the imperial ancestral temple in Nanjing.[96][97][98][99] The military morale of Sheng Yong forces received a significant boost, and the Yan forces stayed clear of Shandong in subsequent attacks.[100]

Battle of Jia River-Gaocheng[edit]

The defeat at Dongchang was a humiliating loss for Zhu Di, but his close advisor Yao Guangxiao supported continuing military operations.[101] The Yan forces mobilised again on 16 February 1401 and marched southwards.[102]

In anticipation of a Yan strike, Sheng Yong stationed himself in Dezhou with 200,000 troops, while placing the remainder of the forces in Zhending. Zhu Di decided to strike Sheng Yong first.[103] On 20 March, the Yan forces encountered the forces of Sheng Yong on Jia River near Wuyi.[104] On 22 March, the Yan forces crossed the Jia River. Seeing that the camp of Sheng Yong was heavily guarded, Zhu Di decided to personally scout the opponent to search for weak spots. Since Jianwen Emperor forbade the killing of Zhu Di, the government forces refrained from shooting at Zhu Di as he scouted around with minimal harassment.[105][106]

After the scouting operation, Zhu Di led the Yan forces and attacked the left wing of Sheng Yong. The ensuing battle lasted until nightfall, in which both sides suffered an equal number of casualties.[107][108] Both sides engaged again the next day. After several hours of intense fighting, the wind suddenly started to blow from the northeast to southwest toward the government positions. The government forces were unable to battle against the wind as the Yan forces ran over their positions. Sheng Yong was forced to retreat to Dezhou.[109][110][111] Government reinforcements from Zhending also retreated after hearing the news of Sheng Yong's defeat.[112]

The Battle of Jia River re-established the military edge for Prince of Yan. On 4 March 1401, Qi Tai and Huang Zicheng were held accountable for the loss and were dismissed from their post. The emperor instructed them to recruit troops from other areas.[113]

After the defeat of Sheng Yong in Jia River, the Yan forces advanced to Zhending. Zhu Di managed to lure the government forces out of the city and engaged them in Gaocheng on 9 March 1401. Facing the gunpowder weapons and crossbows utilised by the government forces, the Yan Army suffered heavy losses.[114][115] The battle ensued the next day, and a severe wind started to blow. The government forces were unable to hold on to its position and were crushed by the Yan forces.[116]

From Baigou River to Jia River and Gaocheng, the Yan forces were aided by the wind in all of these occasions. Zhu Di was convinced that the Yan forces were destined for victory.[117]

Ensuing battles[edit]

In the immediate aftermath of Battle of Jia River-Gaocheng, the Yan forces took the initiative and marched southwards with no resistance.[118] Zhu Di demanded peace talks, and Jianwen Emperor consulted with advisor Fang Xiaoru for opinions. Fang Xiaoru suggested to pretend to negotiate while ordering the forces in Liaodong to strike Beiping.[119][120] The strategy did not work as planned, and in May Sheng Yong sent out an army to attack the supply line of the Yan Army.[121][122] Zhu Di claimed that Sheng Yong refused to stop military actions with ill intentions, and managed to convince Jianwen Emperor to imprison Sheng Yong.[123][124]

As both sides ceased to negotiate, Zhu Di decided to raid the supply line of the government forces to starve the defenders in Dezhou. On 15 June, the Yan forces successfully destroyed the main food storage of the government forces in Pei, and Dezhou was on the brink of collapse.[125] In July, the Yan forces captured Pengde and Linxian.[126] On 10 July 1401, government forces from Zhending launched a raid on Beiping. Zhu Di divided the army to reinforce Beiping and defeated the government forces by 18 September.[127] In hope to reverse the tides of the battle, imperial advisor Fang Xiaoru attempted to intensify the existing distrust between the first and second son of Zhu Di, Zhu Gaochi and Zhu Gaoxu, but the strategy failed once again.[128]

On 15 July 1401, government forces led by Fang Zhao from Datong began to approach Baoding, threatening Beiping, and Zhu Di was forced to withdraw.[129] The Yan forces had a decisive victory in Baoding on 2 October, and Fang Zhao retreated back to Datong.[130] On 24 October, the Yan forces returned to Beiping. The government forces from Liaodong attempted to raid the city again, but the attack was repelled.[131]

The Jingnan Campaign had been ongoing for more than two years up until this point. Despite numerous victories, the Yan forces were unable to hold on to territories due to lack of manpower.[132]

Yan offensives, 1401–1402[edit]

Advancing south[edit]

By the winter of 1401–1402, Zhu Di decided to alter the general offensive strategy. The Yan forces were to skip the strongholds of the government forces, and advance straight south toward the Yangtze River.[133][134]

On 2 December 1401, the Yan forces mobilised and began advancing southward. In the month of January, the Yan forces stormed across Shandong and captured Dong'e, Dongping, Wenshang, and Pei. On 30 January 1402, the Yan forces reached Xuzhou, the major transportation hub.[135]

In response to the mobilisation of the Yan forces, Jianwen Emperor ordered Mei Yin to defend Huai'an, and ordered Xu Huizu to reinforce Shandong.[136][137] On 21 February 1401, the government forces in Xuzhou refused to engage with the Yan forces to focus on defending the city after suffering a defeat.[138]

Battle of Lingbi[edit]

Zhu Di decided to skip Xuzhou and continued to advance southward. The Yan forces went past Suzhou, defended by Pin An, and reached Bengbu by 9 March 1402.[139] Ping An pursued the Yan forces but was ambushed by Zhu Di at Fei River on 14 March, which forced the Pin An to retreat back to Suzhou.[140]

On 23 March 1402, Zhu Di dispatched an army to disrupt the supply line of Xuzhou.[141] The Yan forces arrived at the Sui River on 14 April, and settled across the river facing the government camp. A battle broke out on 22 April in which the government forces led by Xu Yaozu were victorious.[142] As the government forces had victories one after another, the military morale of the Yan forces started to plummet. Soldiers of the Yan forces were mostly from the north, and they were unaccustomed to the heat as summertime approached. The generals of Zhu Di proposed a withdrawal to regroup, which Zhu Di rejected.[143]

During this time, the imperial court received rumours that the Yan forces had retreated back north. Jianwen Emperor recalled Xu Yaozu back to Nanjing, which reduced the government strength north of the Yangtze River.[144] On 25 April 1402, the government forces moved the camp to Lingbi and began to set up fortifications. A series of battles ensued, and the government forces gradually ran out of food supply as the Yan forces successfully blocked their supply line.[145] With the imminent shortage of food supply, the government forces planned to break out of Yan encirclement and regroup in the Huai River. The break out signal was decided as three shots of cannon fire. On the next day, the Yan forces happened to attack Lingbi fortification with the same signal. The government forces completely collapsed in a state of confusion as the Yan forces stormed to take over and ended the battle.[146][147][148]

The main strength of the government forces was crushed decisively in the Battle of Lingbi, and the Yan forces were now unmatched north of the Yangtze River.

Fall of Nanjing[edit]

After the Battle of Lingbi, the Yan forces advanced straight toward the southeast and captured Sizhou on 7 May 1402.[149] Sheng Yong attempted to set up a defensive line on the Huai River to prevent the Yan forces from crossing. As the attack was halted in Huai’an, Zhu Di divided the army and launched a converging attack on Sheng Yong. Sheng Yong was defeated, and the Yan forces captured Xuyi.[150][151]

On 11 May 1402, the Yan forces marched toward Yangzhou, and the city surrendered one week later.[152] The nearby city of Gaoyou also surrendered soon after.[153]

The fall of Yangzhou was a devastating blow for the government forces, as the imperial capital Nanjing was now exposed to a direct attack. After discussing with Fang Xiaoru, the Jianwen Emperor decided to negotiate again with Zhu Di to delay the attack while calling for help from other provinces.[154] The nearby provinces of Suzhou, Ningbo, and Huizhou all dispatched an army to protect the imperial capital.[155]

On 22 May 1402, Zhu Di rejected the negotiation for armistice.[156] On 1 June, the Yan forces were about to cross the Yangtze River, but was met with firm resistance from Sheng Yong. After suffering a few setbacks, Zhu Di was considering whether to accept the peace offer and withdraw back to the north. Zhu Gaoxu arrived with reinforcement in a decisive moment and crushed the forces of Sheng Yong.[157] During the preparation for river crossing, the Yan forces obtained several warships from the government navy. The Yan forces crossed the Yangtze River from Guazhou on 3 June, and Sheng Yong was once again defeated. On 6 June, Zhenjiang fell to the Yan forces.[158][159]

By 8 June 1402, the Yan forces advanced to 30 km east of Nanjing. The imperial court was in a state of panic, and the Jianwen Emperor frantically dispatched several envoys in hopes to negotiate for armistice. Zhu Di rejected the notion and the Yan forces marched toward the imperial capital.[160]

Nanjing was effectively isolated by 12 June. All messengers dispatched to other provinces were intercepted by the Yan forces, and no reinforcement was in sight for the imperial capital.[161] On 13 July 1402, the Yan forces arrived in Nanjing. The city defenders decided to open up the city gate and surrender without resistance.[162][163][164] With the fall of Nanjing to the Prince of Yan Army, the Jingnan Campaign had drawn to an end.

Aftermath[edit]

As the Yan forces marched into Nanjing, Jianwen Emperor set the imperial palace on fire in despair. While the body of Empress Ma was located afterwards, the body of Jianwen Emperor had vanished and was never found.[165][166] The emperor was alleged to have escaped through the tunnels and went into hiding.[167]

Zhu Di decided to go on and hold an imperial funeral for the emperor to imply his death to the general public.[168] On 17 June 1402, Zhu Di was crowned at the imperial palace and became the Yongle Emperor.[169] All of the Jianwen policies were reversed to the original policies set during the reign of Hongwu Emperor.[170]

On 25 June 1402, Qi Tai, Huang Zicheng and Fang Xiaoru were all executed, and their families exterminated.[171] Various other imperial advisors to the Jianwen Emperor were either executed or committed suicide, and their families were exiled by the new government.[172] Majority of these families were pardoned and allowed to return to their homeland during the reign of Hongxi Emperor.[173]

Influences[edit]

During the early reign of the Yongle Emperor, the territorial princes were restored of their positions. However, they were relocated away from the frontiers, and gradually stripped of their military power. With the subsequent policies enforced by the Yongle Emperor, the emperor was successful in consolidating the power of the central government.[174] In 1426, the Xuande Emperor managed to force all of the territorial princes to renounce their remaining personal army after suppressing the rebellion of Zhu Gaoxu.[174]

The Yongle Emperor began the preparation for relocating the imperial capital to Beiping in 1403, a process that lasted throughout his entire reign.[175][176] The construction of the future Forbidden City along with the restructuring of the Grand Canal were constantly ongoing. In 1420, the reconstruction of Beiping City was completed, and the Ming Dynasty officially relocated the imperial capital to Beiping and renamed the city to Beijing.[177] With the exception of Republic of China between 1928 and 1949, Beijing remains to be the fixed capital of China ever since.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- Huang, Yingjian (1962), Ming-shilu: Ming-Taizong-shilu, China: Zhongwen Chubanshe

- Liang, Yuansheng (2007), The Legitimation of New Orders: Case Studies in World History, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, ISBN 978-9-6299-6239-5

- Ming Yue, Dang Nian (2009), Those Ming Dynasty Stuff, China: China Customs Press, ISBN 978-7-5057-2246-0

- Xia, Xie (1999), Ming Tong Jian (First ed.), Changsha: Yuelu Shushe

- Yin, Luanzhang (1936), Ming Jian Gang Mu (First ed.), Shanghai: Shijie Shuju Chubanshe

- Zhang, Tingyu (1936), Ming shi (First ed.), Shanghai: Shangwu Yinshuguan

- 1399 in Asia

- 1402 in Asia

- 1400 in Asia

- 1401 in Asia

- 14th century in China

- 15th century in China

- Civil wars in China

- Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Asia

- Conflicts in 1399

- Conflicts in 1400

- Conflicts in 1401

- Conflicts in 1402

- Military history of Nanjing

- People of the Jingnan Campaign

- Rebellions in the Ming dynasty

- Yongle Emperor

- Wars of succession involving the states and peoples of Asia

- Military history of Jinan