Sonja Schlesin

| |

|---|---|

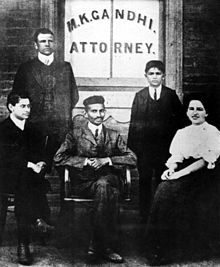

Schlesin is on one side and Henry Polak on the other with Gandhi in centre at his office near what is now Gandhi Square

| |

| Born | (1888-06-06)6 June 1888

Moscow, Russian Empire

|

| Died | 6 January 1956(1956-01-06) (aged 67)

Johannesburg, South Africa

|

| Education | University of the Cape of Good Hope |

| Occupation | Personal assistant |

| Employer | Mohandas Gandhi |

Sonja Schlesin (6 June 1888 – 6 January 1956) was a South African best known for her work with Mohandas Gandhi while he was living in South Africa. She began her service as his secretary at the age of 17. By her early twenties, she had become entrusted with the executive decision making within Gandhi's law practice and sociopolitical movements. Gandhi said "during the Satyagraha days ... she led the movement single handed". She was a lifelong friend to Gandhi and would have been a fellow lawyer if she had not been female. She ended her career as a teacher of Latin and made a late attempt to become a lawyer at the age of 65.

Born in 1888 to a Jewish family in Moscow, Schlesin moved to South Africa with her parents Isidor and Helena Dorothy Schlesin (born Rosenberg) in 1892. By the age of fifteen, she had matriculated at the University of the Cape of Good Hope, which was the city where her family lived. She was recommended for a job by the architect Hermann Kallenbach to a new immigrant Indian lawyer named Mohandas Gandhi.[1] Kallenbach described her as honest and clever, but mischievous and impetuous.[2] Gandhi was so impressed by Schlesin and her speed at shorthand that he offered her a generous wage which she turned down for a more modest figure initially suggested by Kallenbach. Schlesin told Gandhi that she wanted to work for him because she supported his work and not for the money that he was offering.[1] She affectionately called her employer Gandhi 'Bapu' (Father).[3]

Gandhi would take on large administrative and important tasks. In 1904 he persuaded the authorities to rehouse gold mine workers in the Transvaal where the pneumonic plague was taking a toll. Gandhi had taken on the problem and his legal office team had been reassigned to nursing for the sick. The workers' old houses had to be burnt and the dispossessed had only the money that they had buried for safekeeping. Gandhi became their banker and took in about £60,000. This needed to be accounted for so that he could successfully return it several years later.[4]

In 1908 the South African government introduced the "Restriction Act" which was further legal discrimination and was known as the "Black Act". It was Schlesin who wrote a speech for herself to give to 2,500 protesters and asked her parents for permission to deliver it. In the end, it was Gandhi who delivered it, but it was Schlesin's speech that challenged the people "to give up all, aye very life itself, for the noble cause of country and religion". The Chinese community awarded Schlesin a gold watch and the Indian community gave her ten pounds.[5] Schlesin took to smoking and wearing a collar and tie and she cut her hair short. She also included the suffragists as examples of protest in speeches she wrote. The smoking led to Gandhi slapping her when she smoked in his presence.[2]

Schesin was rewarded by Gandhi with a proposal to article her as a clerk and aspiring lawyer,[1] but the application was rejected on the basis of Schlesin's gender.[5][6] In April 1909, the High Court in Pretoria "declined to depart from the universal practice, which precluded the admission of ladies as attorneys…"[1] In the same year Schlesin became secretary of the Transvaal Indian Women's Association because there were no educated Indian women who could take the position. Gandhi went to London that year and left his affairs confidently under the charge of Schlesin.[1] She was entrusted with large sums of money and the trust to make executive decisions despite her age.[5][7]

When Gopal Krishna Gokhale visited South Africa on 22 October 1912 for political discussions across the country for six weeks he was accompanied by Gandhi. Gokhale said his primary reason for visitation was encouraging the return of Gandhi to India. Gandhi asked Gokhale to evaluate the current Indian leadership and the people he had met in South Africa. Gokhale's assessment of the leaders was reportedly very accurate and noted Schlesin in particular for her outstanding talent, energy, ability and service within Gandhi's entourage.[5] Her dedication to Gandhi and his work went beyond the risks that she was taking as a Jewish white woman working for an immigrant man from India.[8]

In 1913 Gandhi led striking South African miners on a great march to protest their conditions and the lack of respect shown to them. This was a bold move as Gandhi was relying on his own finances and the good will of the community to prevent the marchers from suffering hunger. The strike was staged in response to taxation specifically targeting Indian miners who refused to leave South Africa upon the completion of their employment. The support of Kallenbach and Schlesin was instrumental due to their ability to capitalize on their "white credentials" to muster support from the greater Anglo community, while further using the same status as protection from arrest and prosecution.[2]

Gandhi returned to Britain in 1914 and Schlesin decided to remain in South Africa despite Gandhi's profuse thanks to her at farewell dinners in Cape Town, Johannesburg and Durban. Schlesin enrolled at the University College of Johannesburg which she funded with a loan that Gandhi arranged. By 1924 she had earned two degrees of the first class, a Bachelor and Master of Arts, respectively, from the University of Witwatersrand. Schlesin became a well respected but eccentric teacher of Latin at a high school in Krugersdorp for over 20 years with only two students having ever failed her course. Despite this record she was never promoted and this may have been due to frictions with her faculty authorities. She stood up for her beliefs and would astound students by returning Christmas presents that were given to her.[5]

Schlesin outlived Gandhi who was assassinated in 1948. She enrolled at the University of Natal in 1953 to study law but she did not complete the curriculum presumably due to her or the ill health of her sister Rose. Schlesin died in Johannesburg in 1956 and her ashes were placed in a wall of remembrance at Braamfontein Cemetery in Johannesburg.[1]

Gandhi wrote of her in glowing terms in his autobiography noting her ability to work night and day without prejudice or favour. She worked unescorted and asked for little reward and "during the Satyagraha days, almost everyone of the leaders was in jail, she led the movement single handed".[7]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|