|

removed WP:SYNTHESIS and special pleading, per talkpage

|

m →Greek public opinion: typo

|

||

| Line 838: | Line 838: | ||

==Greek public opinion== |

==Greek public opinion== |

||

According to a poll in February 2012 by Public Issue and SKAI Channel, PASOK—which won the national elections of 2009 with 43.92% of the vote—had seen its approval rating decimated to a mere 8%, placing it fifth after centre-right New Democracy (31%), left-wing Democratic Left (18%), far-left Communist Party of Greece (KKE) (12.5%) and radical left SYRIZA (12%). The same poll suggested that [[George Papandreou| |

According to a poll in February 2012 by Public Issue and SKAI Channel, PASOK—which won the national elections of 2009 with 43.92% of the vote—had seen its approval rating decimated to a mere 8%, placing it fifth after centre-right New Democracy (31%), left-wing Democratic Left (18%), far-left Communist Party of Greece (KKE) (12.5%) and radical left SYRIZA (12%). The same poll suggested that [[George Papandreou|Papandreou]] is the least popular political leader with a 9% approval rating, while 71% of Greeks do not trust Papademos as prime minister.<ref name="PollFeb2012">{{cite web|title=Poll Feb2012|url=http://www.skai.gr/news/politics/article/193925/antigrafotouvarometro-neo-politiko-skiniko-me-okto-kommata-sti-vouli-/|accessdate=14 Feb 2012|date=14 Feb 2012}}</ref> |

||

In a poll published on 18 May 2011, 62% of the people questioned felt the IMF memorandum that Greece signed in 2010 was a bad decision that hurt the country, while 80% had no faith in the [[Minister for Finance (Greece)|Minister of Finance]], [[Giorgos Papakonstantinou]], to handle the crisis.<ref name="Public Issue">{{cite web|title=Mνημόνιο ένα χρόνο μετά: Aποδοκιμασία, αγανάκτηση, απαξίωση, ανασφάλεια (One Year after the Memorandum: Disapproval, Anger, Disdain, Insecurity)|url=http://www.skai.gr/news/politics/article/169875/mnimonio-ena-hrono-meta-apodokimasia-aganaktisi-apaxiosi-anasfaleia|publisher=skai.gr|accessdate=18 May 2011|date=18 May 2011}}</ref> ([[Evangelos Venizelos]] replaced Papakonstantinou on 17 June). 75% of those polled gave a negative image of the IMF, and 65% feel it is hurting Greece's economy.<ref name="Public Issue" /> 64% felt that the possibility of sovereign default is likely. When asked about their fears for the near future, Greeks highlighted unemployment (97%), poverty (93%) and the closure of businesses (92%).<ref name="Public Issue" /> |

In a poll published on 18 May 2011, 62% of the people questioned felt the IMF memorandum that Greece signed in 2010 was a bad decision that hurt the country, while 80% had no faith in the [[Minister for Finance (Greece)|Minister of Finance]], [[Giorgos Papakonstantinou]], to handle the crisis.<ref name="Public Issue">{{cite web|title=Mνημόνιο ένα χρόνο μετά: Aποδοκιμασία, αγανάκτηση, απαξίωση, ανασφάλεια (One Year after the Memorandum: Disapproval, Anger, Disdain, Insecurity)|url=http://www.skai.gr/news/politics/article/169875/mnimonio-ena-hrono-meta-apodokimasia-aganaktisi-apaxiosi-anasfaleia|publisher=skai.gr|accessdate=18 May 2011|date=18 May 2011}}</ref> ([[Evangelos Venizelos]] replaced Papakonstantinou on 17 June). 75% of those polled gave a negative image of the IMF, and 65% feel it is hurting Greece's economy.<ref name="Public Issue" /> 64% felt that the possibility of sovereign default is likely. When asked about their fears for the near future, Greeks highlighted unemployment (97%), poverty (93%) and the closure of businesses (92%).<ref name="Public Issue" /> |

||

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

The Greek government-debt crisis (also known as the Greek Depression[3][4][5]) started in late 2009, as the first of four sovereign debt crises in the eurozone - later referred to collectively as the European debt crisis. The common view holds that it was triggered by the turmoil of the Great Recession, but that the root cause for its eruption in Greece was a combination of structural weaknesses in the Greek economy along with a decade-long pre-existence of overly high structural deficits and debt-to-GDP levels of public accounts. In late 2009, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed among investors concerning Greece's ability to meet its debt obligations, due to a reported strong increase in government debt levels along with continued existence of high structural deficits.[6][7][8] This led to a crisis of confidence, indicated by a widening of bond yield spreads and the cost of risk insurance on credit default swaps compared to the other Eurozone countries - Germany in particular.[9][10]

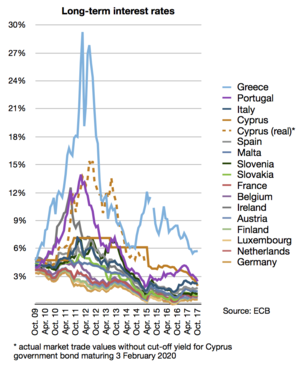

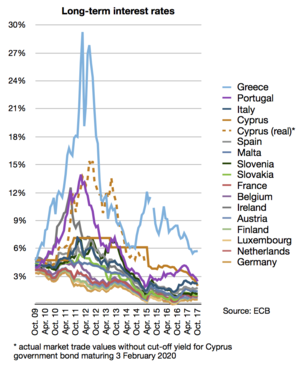

In April 2010, adding to news of the recorded adverse deficit and debt data for 2008 and 2009, the national account data revealed that the Greek economy had also been hit by three distinct recessions (Q3-Q4 2007, Q2-2008 until Q1-2009, and a third starting in Q3-2009),[11] which equaled an outlook for a further rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio from 109% in 2008 to 146% in 2010. Credit rating agencies responded by downgrading the Greek government debt to junk bond status (below investment grade), as they found indicators of a growing risk of a sovereign default, and the government bond yields responded by rising into unsustainable territory - making the private capital lending market inaccessible as a funding source for Greece.

On 2 May 2010, the Eurozone countries, European Central Bank (ECB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF), later nicknamed the Troika, responded by launching a €110 billion bailout loan to rescue Greece from sovereign default and cover its financial needs throughout May 2010 until June 2013, conditional on implementation of austerity measures, structural reforms, and privatization of government assets. A year later, a worsened recession along with a delayed implementation by the Greek government of the agreed conditions in the bailout programme revealed the need for Greece to receive a second bailout worth €130 billion (including a bank recapitalization package worth €48bn), while all private creditors holding Greek government bonds were required at the same time to sign a deal accepting extended maturities, lower interest rates, and a 53.5% face value loss. The second bailout programme was finally ratified by all parties in February 2012, and by effect extended the first programme, meaning a total of €240 billion was to be transferred at regular tranches throughout the period of May 2010 to December 2014. Due to a worsened recession and continued delay of implementation of the conditions in the bailout programme, in December 2012 the Troika agreed to provide Greece with a last round of significant debt relief measures, while the IMF extended its support with an extra €8.2bn of loans to be transferred during the period of January 2015 to March 2016.

The fourth review of the bailout programme revealed development of some unexpected upcoming financing gaps.[12][13] Due to an improved outlook for the Greek economy, with achievement of a government structural surplus both in 2013 and 2014 - along with a decline of the unemployment rate and return of positive economic growth in 2014,[14][15] it was possible for the Greek government to regain access to the private lending market for the first time since eruption of its debt crisis - to the extent that its entire financing gap for 2014 was patched through a sale of bonds to private creditors.[16]

The improved economic outlook was replaced by a new fourth recession starting in Q4-2014,[17] related to the premature snap parliamentary election called by the Greek parliament in December 2014 and the following formation of a Syriza-led government refusing to accept respecting the terms of its current bailout agreement.[18] The rising political uncertainty of what would follow, caused the Troika to suspend all scheduled remaining aid to Greece under its current programme - until such time when the Greek government either accepted the previously negotiated conditional payment terms or alternately could reach a mutually accepted agreement of some new updated terms with its public creditors.[19] This rift caused a renewed and increasingly growing liquidity crisis (both for the Greek government and Greek financial system), resulting in plummeting stock prices at the Athens Stock Exchange, while interest rates for the Greek government at the private lending market spiked, making it once again inaccessible as an alternative funding source.

After the election, the Eurogroup granted a further four-month technical extension of its current bailout programme to Greece; accepting the payment terms attached to its last tranche to be renegotiated with the new Greek government before the end of April,[20] so that the review and last financial transfer could be completed before the end of June 2015.[21] The new renegotiation deal was still pending by the end of May.[22][23] Faced by the threat of sovereign default, which inevitably would entail enforcement of recessionary capital controls to avoid a collapse of the banking sector - and potentially could lead to exit from the eurozone due to growing liquidity constraints making continued payment of public pension and salaries impossible in euro,[24][25] some final attempts for reaching a renegotiated bailout agreement were made by the Greek government in June 2015.[26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51]

Expectations are, that Greece, besides ultimately receiving its remaining transfer of frozen bailout funds in its second programme, will need a follow-up support programme starting 1 July 2015. The Troika announced that their premise to offer Greece (and begin negotiations about the establishment of) a follow-up third bailout programme would be a prior successful completion of the re-negotiated current second bailout programme.[52][53]

The downgrading of Greek government debt to junk bond status in April 2010 created alarm in financial markets, with bond yields rising so high, that private capital markets were practically no longer available for Greece as a funding source. On 2 May 2010, the Eurozone countries and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) agreed on a €110 billion bailout loan for Greece, conditional on compliance with the following three key points:

The payment of the bailout was scheduled to happen in several disbursements from May 2010 until June 2013. Due to a worsened recession and the fact that Greece had worked slower than expected to comply with point 2 and 3 above, there was a need one year later to offer Greece both more time and money in the attempt to restore the economy. In October 2011, Eurozone leaders consequently agreed to offer a €130 billion second bailout loan for Greece, conditional not only on the implementation of another austerity package (combined with the continued demands for privatisation and structural reforms outlined in the first programme), but also that most private creditors holding Greek government bonds should sign a deal accepting extended maturities, lower interest rates, and a 53.5% face value loss.

This proposed restructure of all Greek public debt held by private creditors, which at that point of time constituted a 58% share of the total Greek public debt, would according to the bailout plan reduce the overall public debt burden with roughly €110 billion. A debt relief equal to a lowering of the debt-to-GDP ratio from a forecast 198% in 2012 down to roughly 160% in 2012, with the lower interest payments in subsequent years combined with the agreed fiscal consolidation of the public budget and significant financial funding from a privatization program, expected to give a further debt decline to a more sustainable level at 120.5% of GDP by 2020.

The second bailout deal was finally ratified by all parties in February 2012, and became active one month later, after the last condition regarding a successful debt restructure of all Greek government bonds had also been met. The second bailout plan was designed with appointment of the Troika (the EU, ECB and IMF) to cover all Greek financial needs from 2012 to 2014 through a transfer of some regular disbursements; and aimed for Greece to resume using the private capital markets for debt refinance and as a source to partly cover its future financial needs, already in 2015. In the first five years from 2015 to 2020, the return to use the markets was however only evaluated as realistic to the extent, where roughly half of the yearly funds needed to patch the continued budget deficits and ordinary debt refinance should be covered by the market; while the other half of the funds should be covered by extraordinary income from the privatization program of Greek government assets.

In mid-May 2012 the crisis and impossibility to form a new coalition government after elections, led to strong speculation Greece would have to leave the Eurozone.[54] The potential exit became known as "Grexit" and started to affect international market behavior. A second election in mid-June, ended with the formation of a new government supporting a continued adherence to the main principles outlined by the signed bailout plan. The new government however immediately asked its creditors, due to a delayed reform schedule and a worsened economic recession, to be granted an extended deadline from 2015 to 2017 before being required to restore the budget into a self-financed situation; which in effect was equal to a request for the Troika to pay two more years of additional funds in the form of a third bailout package for 2015–16 (or alternatively asking private creditors to accept writing off new additional amounts of debt).[55] In July 2012, the Troika started to examine this request in the light of an updated and recalculated sustainability analysis of the Greek economy, and were at first expected already to publish a report with their findings by the end of August 2012.[56]

As initial findings indicated the bailout programme was widely off track, the Troika decided to withhold the scheduled €31.5bn bailout disbursement for August 2012; with the message that the transfer awaited reassurance by the first review report of the programme, that Greece had managed to put the bailout plans conditional implementation of measures back on track, and still were committed to follow the agreed path to restore and reform the economy.[57] The subsequent three months were used by the Greek government to negotiate with the Troika about the exact content of the conditional "Labor market reform" and "Midterm fiscal plan 2013–16", in order to put the bailout plan back on track. The two major bills featured all together austerity measures worth €18.8bn, of which the first €9.3bn were scheduled for 2013. In return, the Troika indicated a willingness to accept paying a third bailout loan on €30bn to finance the two-year extension of the bailout programme, while also looking into solutions for reducing the Greek debt into a sustainable size (i.e. through the launch of a debt-buy-back programme for private held government bonds and/or offering debt-relief measures in the form of lower interest rates combined with prolonged debt maturities).[58]

On 7 November 2012, facing the alternative of a default by the end of November if not passing the negotiated Troika package,[58] the Greek parliament passed the conditional "Labor market reform" and "Midterm fiscal plan 2013–16" with 153 out of 300 MPs voting yes, and the parliament late on 11 November finally also passed the "Fiscal budget for 2013" with the support by 167 out of 300 MPs. The conclusion of the Troika's long awaited first review report of the bailout programme, had for a long pended the outcome of the Greek parliament's pass of the mentioned bills.[59][60] As all three bills were passed as planned, the Troika report was printed and distributed to the Eurogroup a few minutes later on 11 November, in its first complete draft version. The report mapped the status for implemented programme measures and the state of the Greek economy, structural reforms, privatisation programme and debt sustainability. Among other things the draft report found, that the 2-year extension of the bailout programme would cost €32.6bn of extra loans from the Troika (€15bn in 2013–14 and €17.6bn in 2015–16).[61] In December 2012, the Eurogroup decided not to transfer a third bailout loan, but instead approved an adjustment-package together with ECB and IMF, featuring a set of debt relief measures for the already granted EFSF debt pile (lower interest rate and longer maturity) along with reimbursement of all Greek interest payments paid on Troika held debt until 2020, effectively closing the entire fiscal financing gap for 2013–16. As part of this adjustment agreement, IMF however delivered its reimbursement of interests in the form of some new bailout loan tranches, worth €8.2bn, to be paid at regular intervals between January 2015 and 14 March 2016.[62][63] A final element of the adjustment package, was a pre-required debt buyback by the Greek government of roughly 50% of the remaining PSI bonds, which also helped to lower the debt-to-GDP ratio with 10.6 benchmark points, helping the country to maintain a sustainable debt outlook for 2020.

Both of the latest bailout programme audit reports, released independently by the European Commission and IMF in June 2014, revealed that even after transfer of the scheduled bailout funds and full implementation of the agreed adjustment package in 2012, there was a new forecast financing gap of: €5.6bn in 2014, €12.3bn in 2015, and €0bn in 2016. The new forecast financing gaps, will need either to be covered by the government's additional lending from private capital markets, or to be countered by additional fiscal improvements through expenditure reductions, revenue hikes or increased amount of privatizations.[12][13] Due to an improved outlook for the Greek economy, with return of a sustained government structural surplus since 2013 along with a return of real GDP growth and a decline of the unemployment rate in 2014,[14][15] it was possible for the Greek government to return to the bond market during the course of 2014 – for the purpose to fully fund its new extra financing gaps by additional private capital. A total of €6.1bn was raised from the sale of three-year and five-year bonds in 2014, and the Greek government now plans to cover its forecast financing gap for 2015 by additional sale of seven-year and ten-year bonds in 2015.[16]

The latest recalculation of the seasonally adjusted quarterly GDP figures for the Greek economy, revealed that it had been hit by three distinct recessions in the turmoil of the Global Financial Crisis:[11]

Greece experienced positive economic growth in each of the 3 first quarters of 2014.[11] The return of economic growth, along with the now existing underlying structural budget surplus of the general government, build the basis for the debt-to-GDP ratio to start a significant decline in the coming years ahead,[64] which will help ensure that Greece will be labeled "debt sustainable" and fully regain complete access to private lending markets in 2015.[a] While the Greek government-debt crisis hereby is forecast officially to end in 2015, it shall be noted this positive forecast is based on the "assumption Greece will meet the primary surplus targets of its [bailout] programme in 2015 and 2016 – as a result of the fiscal-structural reforms under its [bailout] programme and the improved economic environment".[64]

During the second half of 2014, the Greek government again negotiated with the Troika. The negotiations were this time about how to comply with the programme requirements, to ensure activation of the payment of its last scheduled eurozone bailout tranche in December 2014, and about a potential update of its remaining bailout programme for 2015–16. When calculating the impact of the 2015 fiscal budget presented by the Greek government, there were a disagreement, with the calculations of the Greek government showing it fully complied with the goals of its agreed "Midterm fiscal plan 2013–16", while the Troika calculations were less optimistic and returned a not covered financing gap at €2.5bn (being required to be covered by additional austerity measures).[67] As the Greek government insisted their calculations were more accurate than those presented by the Troika, they submitted an unchanged fiscal budget bill to the parliament, which was passed by 155 against 134 votes on the midnight of 7 December.[68] The Eurogroup met on 8 December and agreed to support a technical two-month extension of the part of the Greek bailout programme under its guidance, making time both for completion of the long awaited fifth final programme review and assessing the possibility for the European Stability Mechanism to set up a precautionary Enhanced Conditions Credit Line (ECCL) in place by 1 March 2015.[69] The press recently rumored that the Greek government had proposed to put an immediate end to the previously agreed and continuing IMF bailout programme for 2015–16, replacing it with the transfer of €11bn unused bank recapitalization funds currently held as reserve by HFSF, along with establishment of the precautionary ECCL. The ECCL instrument is often used as a follow-up precautionary measure, when a state has exited its sovereign bailout programme, functioning as an extra backup guarantee mechanism with transfers only taking place if adverse financial/economic circumstances materialize, but with the positive effect that its sole existence help calm down financial markets – making it more safe for investors to buy government bonds – and hereby it will aid the attempt for the government to raise funding capital from the private capital market.[67] In December, the rumor about the premature halt of the ongoing IMF bailout programme was confirmed, with the Troika planning instead to transform it into a precautionary ECCL by the end of February, at the request of the Greek government.[70]

Following the rejection of the government's candidate for president in parliamentary votes during December 2014, a snap parliamentary election was held on 25 January 2015.[71] The premature election threatened to endanger the recently gained Greek economic recovery, because of the political uncertainty of what would follow and the unavoidable delay of continued implementation of structural reforms.[72][73][74] The rising political uncertainty also caused the Troika to suspend all scheduled remaining financial aid to Greece under its bailout programme, while noting its support would only resume pending the formation of a new-elect government respecting the already negotiated terms.[19]

Opinion polls ahead of the election provided the anti-bailout party Syriza – which announced it would not comply with the previously negotiated terms in the bailout-agreement and demand a "write down on most of the nominal value of debt, so that it becomes sustainable" – with a lead, causing adverse developments on financial markets, with the Athens Stock Exchange suffering an accumulated loss of roughly 30% since the start of December 2014, and the interest rate of the ten-year government bond rising from a low of 5.6% in September 2014[75] to 10.6% on 7 January 2015.[76] According to the ECB Executive Board member from France, "It is illegal and contrary to the treaty to reschedule a debt of a state held by a central bank", meaning such a thing would be incompatible with continued membership of the eurozone.[77] However, the risk of a Grexit (Greek exit from the eurozone) as a result of the upcoming elections, were assessed by economists from Commerzbank AG only to be around 25%, if assuming the election would end with the same result as measured by the opinion polls in early January.[78]

The Syriza Party won the election and formed a new government, which declared the old bailout agreement was now cancelled, while requesting acceptance of an extended deadline from 28 February to 31 May 2015 for the process to negotiate a new replacing creditor agreement with the Eurogroup.[79] The Eurogroup responded by granting a further four-month technical extension of its current bailout programme to Greece; accepting the payment terms attached to its last tranche to be renegotiated with the new Greek government before the end of April,[20] so that the review and last financial transfer could be completed before the end of June 2015.[21]

Due to the outlook for a prolonged time with uncertainty about the Greek governments implementation of economic policy, the European Central Bank concluded in early February, that the state now fulfilled all negative conditions (being outside an economic bailout programme while suffering from a junk credit rating) to remit an immediate halt for the Greek financial system to utilize their holdings of Greek government debt as unrestricted collateral when lending cheap liquidity from ECB. As a consequence of this ECB decision, additional pressure was put on Greece’s new government rapidly to deliver a new bailout agreement,[80] which would both help to solve the state's acute liquidity needs and re-open the access for the Greek financial system to lend liquidity more cheaply again from ECB.[81] The ECB at the same time, continued injecting a growing amount of emergency lending to the Greek financial system, to keep it afloat,[82] in a climate where a growing flee of both foreign and domestic private capital was observed, caused by a daily rise of the perceived sovereign-default risk and the associated risk for enforcement of capital controls restricting the access for private savers to withdraw money from their Greek bank accounts.[83] In early May 2015, ECB had an overall exposure towards Greek banks, equal to €110 billion. The vice president of ECB, however clarified ECB only ran a minor risk - even in the event of Greek sovereign default, as the first €70 billion were secured by collateral held by the Greek National Bank while the rest were assumed could be fully recovered from other non-sovereign collateral held by ECB.[84] In the event Greece manage to negotiate a new bailout-deal with the Troika ahead of June 2015, it will benefit not only from the direct release of bailout funds to the state, but also indirectly from a re-opened access for its financial sector to much cheaper liquidity from ECB - while at the same time becoming part and benefiting from the Quantitative Easing bond buying program operated by ECB, which has the prospect to lower yields and help build the ground for increased economic growth.

The prolonged time-span without any active bailout-agreement, caused an increasingly growing liquidity crisis, which resulted in a new fourth recession hitting Greece - starting from Q4-2014.[17][18] According to the European economic forecast published in May 2015, the impact of this sudden unexpected recession for the entire part of 2015, would be that economic growth (real GDP) now only was expected to rise +0.5% compared to the earlier forecast +2.5%; while it was emphasized this attainment of low positive growth for the current year as a whole - was even a best case scenario forecast - at the premise on a fast successful conclusion to the current bailout-programme negotiations held between the Greek government and its public creditors in May 2015. The reason why the economic outlook became downgraded, was because the "positive momentum" building up in 2014 after Greece's savage recession came to an end, had been hurt by the political uncertainty erupting since the announcement in December of early elections, which further intensified after the election - due to the inability of the new-elect government to settle an economic policy agreement with its creditors within its first given deadline in February 2015.[85] The Hellenic Confederation of Commerce and Enterprises (ECEE) estimated, that each day without an active bailout agreement under the new-elect government, had entailed daily costs equal to €22.3 million shrinkage of GDP, bankrupt closure of 59 shops, along with 613 jobs being lost.[86] The political uncertainty, beside of damaging the economic growth, was found also to have caused a "significant shortfall" in collected state revenues beyond what could be explained by the lower growth, which led to a significant downgrade of the forecast Greek general government's structural budget balance in 2015 (declining from a previously forecast +1.6%, now to become negative at -1.4%).[87] Finally, as a result of all these adverse developments, the debt-to-GDP ratio was also forecast to deteriorate, going up from the forecast six months ago of 170.2% in 2015 and 159.2% in 2016, now to be 180.2% in 2015 and 173.5% in 2016, making it increasingly unlikely for Greece to attain its bailout programme target of reaching a 124% ratio in 2020.[88]

Faced by the threat of sovereign default, which inevitably would entail enforcement of recessionary capital controls to avoid a collapse of the banking sector - and potentially could lead to exit from the eurozone due to growing liquidity constraints making continued payment of public pension and salaries impossible in euro,[24][25] some final attempts for reaching a renegotiated bailout agreement were made by the Greek government in June 2015.[22][23][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51] Expectations are that Greece, beside of ultimately receiving its remaining transfer of frozen bailout funds in its second programme, in addition will need a follow-up support programme starting 1 July 2015. The Troika announced their premise to offer Greece (and begin negotiations about) establishment of a follow-up third bailout programme, would be a prior successful completion of the re-negotiated current second bailout programme.[52][53]

In January 2010, the Greek Ministry of Finance in their Stability and Growth Program 2010 listed these five main causes for eruption of the present government-debt crisis and the significantly deteriorated debt-to-GDP ratio in 2009 (compared to what had been forecast one year earlier), and outlined the first plan how to combat the crisis:[89]

In 1981, Greece started to have large fiscal deficits that remained high for a decade. The decade bequeathed the country with two significant problems: high public debt and low competitiveness.[107]

The current account of Greece went into deficit at the beginning of the 1980s, the deficits were initially small and were treated with devaluations. Deficits began to grow since 1996 and especially after the introduction of euro in 2001.[108]

The Greek economy was one of the fastest growing in the Eurozone from 2000 to 2007: during this period it grew at an annual rate of 4.2%, as foreign capital flooded the country.[109] Despite that, the country continued to record high budget deficits each year.

Financial statistics reveal solid budget surpluses existed in 1960–73 for the Greek general government, but since then only budget deficits were recorded.[110][111][112] In 1974–80 the general government had an era with moderate and acceptable budget deficits (below 3% of GDP). Unfortunately this was followed by a long period with very high and unsustainable budget deficits in 1981–2013 (above 3% of GDP).[111][112][113][114]

According to an editorial published by the Greek conservative newspaper Kathimerini, large public deficits were indeed one of the features that have marked the Greek social model since the restoration of democracy in 1974. After the removal of the right-wing military junta, the government wanted to bring disenfranchised left-leaning portions of the population into the economic mainstream.[115] In order to do so, successive Greek governments have, among other things, customarily run large deficits to finance enormous military expenditure, public sector jobs, pensions and other social benefits. Greece is, as a percentage of GDP, the second-biggest defense spender [116] among the 27 NATO countries after the United States, according to NATO statistics. The US is the major beneficiary of Greek military expenditure, with the Americans supplying 42 per cent of its arms, Germany supplying 22.7 per cent, and France 12.5 per cent of Greece's arms purchases.[117]

The long period with high yearly budget deficits caused a situation where, from 1993, the debt-to-GDP ratio was always found to be above 94%.[118] In the turmoil of the global financial crisis the situation became unsustainable (causing the capital markets to freeze in April 2010), as the downturn had caused the debt level rapidly to grow above the maximum sustainable level for Greece (defined by IMF economists to be 120%). According to "The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece" published by the EU Commission in October 2011, the debt level was even expected further to worsen into a highly unsustainable level of 198% in 2012, if the proposed debt restructure agreement was not implemented.[119]

Prior to the introduction of the euro, currency devaluation had helped to finance Greek government borrowing; after the euro's introduction in January 2001, however, the devaluation tool disappeared. Throughout the next 8 years, Greece was however able to continue its high level of borrowing, due to the lower interest rates government bonds in euro could command, in combination with a long series of strong GDP growth rates. Problems however started to occur when the global financial crisis peaked, with negative repercussions hitting all national economies in September 2008. The global financial crisis had a particularly large negative impact on GDP growth rates in Greece. Two of the country's largest earners are tourism and shipping, and both were badly affected by the downturn, with revenues falling 15% in 2009.[120]

Excluding Greek banks, European banks had €45.8bn exposure to Greece in June 2011, with €9.4bn held by French and €7.9bn by German banks.[121]

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman writes, "It’s true that Greece (or more precisely the center-right government that ruled the nation from 2004-9) voluntarily borrowed vast sums. It’s also true, however, that banks in Germany and elsewhere voluntarily lent Greece all that money."[122]

Another persistent problem Greece has suffered in recent decades is the government's tax income. Each year it is below the expected level. In 2010, the estimated tax evasion costs for the Greek government amounted to well over $20 billion per year.[123] The latest figures from 2013, also show that the State only collected less than half of the revenues due 2012, with the remaining tax owings being accepted to be paid by a delayed payment schedule.[124] As of 2012, tax evasion was widespread, and according to Transparency International's Corruption perception index, Greece, with a score of 36/100, ranked as the most corrupt country in the EU.[125][126] One of the conditions of the bailout was implementation of an anti-corruption strategy;[63] Greek government agreed to combat corruption, and the corruption perception level improved to a score of 43/100 in 2014, which was still the lowest in the EU, but now up at the same score as Italy, Bulgaria and Romania.[127][125]

As per news quoted in Swissquote Bank (Switzerland) on 2015-03-25 it is estimated that the amount of "black money" undeclared by Greeks in Swiss banks is around 80 billion EUR or CHF and therefore after the negotiation of a tax treaty by the Greek government which seems to be imminent the Greek government could expect according to experts 10 - 15 billion EUR per year being paid by Swiss banks under the agreement. [128]

Data for 2012[129] place the Greek "black market" at 24.3% of GDP, compared with 28.6% for Estonia, 26.5% for Latvia, 21.6% for Italy, 17.1% for Belgium and 13.5% for Germany (partly in correlation with the percentage of Greek population that is self-employed[130] i.e., 31.9% in Greece vs. 15% EU average,[131] as several studies [132][133] have shown the clear correlation between tax evasion and self-employment).

In early 2010, economy commissioner Olli Rehn denied that other countries would need a bailout. He said, "Greece has had particularly precarious debt dynamics and Greece is the only member state that cheated with its statistics for years and years."[134] It was revealed that Goldman Sachs and other banks had helped the Greek government to hide its debts. Other sources said that similar agreements were concluded in "Greece, Italy, and possibly elsewhere".[135][136] The deal with Greece was "extremely profitable" for Goldman. Christoforos Sardelis, former head of Greece’s Public Debt Management Agency, said that the country didn’t understand what it was buying. He also said he learned that "other EU countries such as Italy" had made similar deals.[137] This led to questions about what other countries had made similar deals.[138][139][140]

According to Der Spiegel credits given to European governments were disguised as "swaps" and consequently did not get registered as debt because Eurostat at the time ignored statistics involving financial derivatives. A German derivatives dealer had commented to Der Spiegel that "The Maastricht rules can be circumvented quite legally through swaps," and "In previous years, Italy used a similar trick to mask its true debt with the help of a different US bank."[140] These conditions had enabled Greek as well as many other European governments to spend beyond their means, while meeting the deficit targets of the European Union.[135][141] In May 2010, the Greek government deficit was again revised and estimated to be 13.6%[142] which was the second highest in the world relative to GDP with Iceland in first place at 15.7% and Great Britain third with 12.6%.[143] Public debt was forecast, according to some estimates, to hit 120% of GDP during 2010.[144]

To keep within the monetary union guidelines, the government of Greece had also for many years misreported the country's official economic statistics.[145][146] At the beginning of 2010, it was discovered that Greece had paid Goldman Sachs and other banks hundreds of millions of dollars in fees since 2001, for arranging transactions that hid the actual level of borrowing.[147] Most notable is a cross currency swap, where billions worth of Greek debts and loans were converted into Yen and Dollars at a fictitious exchange rate by Goldman Sachs, thus hiding the true extent of Greek loans.[148]

The purpose of these deals made by several successive Greek governments, was to enable them to continue spending, while hiding the actual deficit from the EU, which, at the time, was a common practice amongst many European governments.[147] The revised statistics revealed that Greece at all years from 2000 to 2010 had exceeded the Eurozone stability criteria, with the yearly deficits exceeding the recommended maximum limit at 3.0% of GDP, and with the debt level significantly above the recommended limit of 60% of GDP.

The European statistics agency, Eurostat, had at regular intervals ever since 2004, sent 10 delegations to Athens with a view to improving the reliability of statistical figures related to the Greek national account, but apparently to no avail. In January 2010, it issued a damning report which contained accusations of falsified data and political interference.[149]

In February 2010, the new government of George Papandreou (elected in October 2009), admitted a flawed statistical procedure previously had existed, before the new government had been elected, and revised the 2009 deficit from a previously estimated 6%-8% to an alarming 12.7% of GDP.[150] In April 2010, the reported 2009 deficit was further increased to 13.6%,[151] and at the time of the final revised calculation by Eurostat's standardized method had been performed, it ended at 15.7% of GDP, which proved to be the highest deficit for any EU country in 2009. A former employee at the Greek statistics office subsequently argued in January 2013, that it caused "incorrect results" to use the same standardized Eurostat methodology, as all other EU member states currently use.[152][153][154][155] After the complaint had been investigated by financial prosecutors, it was however concluded, that the decision to replace the old incompliant Greek calculation method by Eurostat's standard method, had been fully correct.[citation needed]

The figure for Greek government debt at the end of 2009, was also increased from its first November estimate at €269.3 billion (113% of GDP),[156][157] to a revised €299.7 billion (130% of GDP). The need for a major and sudden upward revision of both the deficit and debt level for 2009, only being realized at a very late point, arose due to Greek authorities previously having published flawed estimates and statistics in 2009. To sort out all Greek statistical issues once and for all, Eurostat then decided to perform their own in depth Financial Audit of the fiscal years 2006–09. After having conducted the financial audit, Eurostat noted in November 2010, that all "methodological issues" now had been fixed, and that the new revised figures for 2006–2009 finally were considered to be reliable.[158][159][160]

Despite the crisis, the Greek government's bond auction in January 2010 had the offered amount of €8bn 5-year bonds over-subscribed by four times.[161] At the next auction in March, the Financial Times again reported: "Athens sold €5bn in 10-year bonds and received orders for three times that amount".[162] The continued successful auction and sale of bonds, was however only possible at the cost of increased yields, which in return caused a further worsening of the Greek public deficit. As a result, the rating agencies downgraded the Greek economy to junk status in late April 2010. In practical terms this caused the private capital market to freeze, so that all the Greek financial needs instead had to be covered by international bailout loans, in order to avoid a sovereign default.[163] In April 2010, it was estimated that up to 70% of Greek government bonds were held by foreign investors (primarily banks).[157] The subsequent bailout loans paid to Greece were mainly used to pay for the maturing bonds, but also to finance the continued yearly budget deficits.

The table below display all relevant historical and forecasted data for the Greek government budget deficit, inflation, GDP growth and debt-to-GDP ratio.

The first period with accelerating debt-to-GDP ratios stretched from 1980 to 1996, where it increased from 21% to 95% due to some years characterized by: low real GDP growth, high structural deficits, high inflation, high interest rates and multiple currency devaluations. In 1996–1999, the solution that brought the Greek economy back on a sustainable track, was the combination of enforcing a "hard drachma policy" and some consistent yearly reductions of the structural deficits through implementing austerity measures. This in turn caused inflation and interest rates to decline, which created the foundation for significant real GDP growth and at the same time put a halt to the accelerating trend for the debt-to-GDP ratio. The statistics reveal 1999 (which was the year Greece managed to qualify for the later euro adoption on 1 January 2001), to be the most "sustainable year" since 1980. Yet the lowering of the budget deficit to 3.1% and the related structural deficit to 3.6%, was still slightly above the limits required by the Stability and Growth Pact, and only good enough to stabilize the problem with the accelerating debt-to-GDP ratio, for as long as strong real GDP growth (along with market access to fund the government debt at low interest rates) continued in the subsequent years.

The second period with accelerating debt-to-GDP ratios was in 2008–13, where the ratio grew from 103% ultimo 2007 to 175% ultimo 2013; and in fact would have been up at a record high 216% ultimo 2013, if the debt haircut and debt buy-back towards private holders of Greek Government bonds had not been performed in 2012. The accelerating trend in the ratio, was this time triggered by the onset of the global recession in 2008, also known as the Great Recession, which caused some related high budget deficits in 2008–13. The root cause behind the problem where Greece got stuck in a prolonged period of accelerating debt-to-GDP ratios, starting in 2008, was however that Greece had failed to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio during the good years with strong economic growth in 2000–07, where shifting governments instead had opted to continue on a path of running high annual structural deficits in the range of 4.2–7.8% of GDP.

As a consequence of the unhealthy fiscal policy practiced during 2000–07, Greece was left with a twofold problem in 2008.

The first part of the problem was a too-high pre-existing debt level, leaving no room to absorb the increasing debts generated through a recession period without the market considering the debt pile would reach an unsustainable size, creating the so-called negative spiral of "interest rate death", which occurs if a country suffers from a constantly increasing debt that exceeds the sustainable level (at which the state is no longer forecast in the long run to be able to refinance or pay back its debt), which will mean the financial markets will start to ask higher and higher interest rates to cover the increasing risk for default. Higher interest rates will then cause an even more unsustainable debt-level, due to the increased government budget deficits stemming from increased interest payments, which will result in some still higher interest rates being required by the market; and the speed of this self-sustaining negative trend will likely keep accelerating until death occurs in form of a sovereign default, or alternatively trigger a situation where the government receive a sovereign bailout (with cheaper funding delivered by other sovereign states on favorable conditions through multiple years—as a last chance for the state to restructure its economy to enter into a more sustainable path).

The second part of the problem behind the accelerating debt-to-GDP ratio, also needing to be solved immediately, was the underlying fundamental problem of continued existence of way too high structural deficits of the government budget. Only starting from 2010, significant efforts and results were achieved in minimizing the structural deficits, through implementation of yearly packages with significant austerity measures. The conducted necessary fiscal consolidation, which as a negative side-effect on the short term caused a worsened recession, resulted in Greece for the first time since 1973 achieved a structural surplus in 2012, which was maintained through all following years. Achieving and maintaining a structural surplus is important, as it provides the foundation for the debt-to-GDP ratio gradually to decline down towards more sustainable levels, from the very moment when GDP growth will return to the country. The long awaited reappearance of GDP growth, came in Q1-2014, and it is forecast to increase to a high stable level around 3–4% during 2015–17, provided that Greece will stick to the implementation of all the needed measures (structural reforms + privatisations + targeted investments) outlined in its bailout programme signed with the Troika.

Besides the restoring of the structural balance, in order to build the foundation for debt-to-GDP ratios to decline back to sustainable levels, it was also needed to implement a debt restructure in March 2012. This debt restructure not only converted "high rate bonds with short maturity" to "low rate bonds with long maturity" (which significantly lowered the debt costs), but also introduced a direct 53.5% haircut to the nominal value of all government debt held by private bond owners. The haircut alone, lowered the government debt pile by €106.5bn (equal to a debt-to-GDP ratio decline of 55.0 percentage points), but as Greek banks at the same time were holding almost 1/3 of the restructured debt, this also created the need for the Troika and Greek government to pay for a €48.2bn bank recapitalisation in 2012, which added back an additional 24.9 percentage points to the debt-to-GDP ratio. So all in all the net impact of the debt restructure in March 2012, was that it lowered the debt-to-GDP ratio with 30.1 percentage points. In addition, the Greek government in December 2012 also completed a debt buyback of 50% of the remaining PSI bonds,[164] where the issuance of €11.3bn EFSF bonds financed the buying of PSI bonds representing a nominal debt of €31.9bn, thus resulting in a €20.6bn net decline of debt (equal to a debt-to-GDP ratio decline of 10.6 percentage points).[165] Overall the two debt restructuring measures accounted for a 40.7 percentage point debt-to-GDP decline, so that it only ended at 156.9% ultimo 2012, down from the 197.6% it would have ended on if no debt restructure measures had been performed.

| Greek national account | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001a | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015b | 2016b | 2017c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public revenued (% of GDP)[166] | — | — | 31.0d | 37.0d | 37.8d | 39.3d | 40.9d | 41.8d | 43.4d | 41.3d | 40.6d | 39.4d | 38.4d | 39.0d | 38.7 | 40.2 | 40.6 | 38.7 | 41.1 | 43.8 | 45.7 | 47.8 | 45.8 | 48.1 | 45.8 | TBA |

| Public expenditured (% of GDP)[167] | — | — | 45.2d | 46.2d | 44.5d | 45.3d | 44.7d | 44.8d | 47.1d | 45.8d | 45.5d | 45.1d | 46.0d | 44.4d | 44.9 | 46.9 | 50.6 | 54.0 | 52.2 | 54.0 | 54.4 | 60.1 | 49.3 | 50.2 | 47.9 | TBA |

| Budget balanced (% of GDP)[114][168] | — | — | -14.2d | -9.1d | -6.7d | -5.9d | -3.9d | -3.1d | -3.7d | -4.5d | -4.9d | -5.7d | -7.6d | -5.5d | -6.1 | -6.7 | -9.9 | -15.3 | -11.1 | -10.2 | -8.7 | -12.3 | -3.5 | -2.1 | -2.2 | TBA |

| Structural balancee (% of GDP)[169] | — | — | −14.9f | −9.4g | −6.9g | −6.3g | −4.4g | −3.6g | −4.2g | −4.9g | −4.5g | −5.7h | −7.7h | −5.2h | −7.4h | −7.8h | −9.7h | −14.7h | −9.8 | −6.3 | -0.6 | 2.2 | 0.4 | -1.4 | -2.3 | TBA |

| Nominal GDP growth (%)[170] | 13.1 | 20.1 | 20.7 | 12.1 | 10.8 | 10.9 | 9.5 | 6.8 | 5.6 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 10.0 | 8.1 | 3.2 | 9.4 | 6.9 | 4.0 | −1.9 | −4.7 | −8.2 | −6.5 | −6.1 | −1.8 | -0.7 | 3.6 | TBA |

| GDP price deflatori (%)[171] | 3.8 | 19.3 | 20.7 | 9.8 | 7.7 | 6.2 | 5.2 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.1 | −2.3 | −2.6 | -1.2 | 0.7 | TBA |

| Real GDP growthj (%)[172][173] | 8.9 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 6.6 | 5.0 | 0.9 | 5.8 | 3.5 | −0.4 | −4.4 | −5.4 | −8.9 | −6.6 | −3.9 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 2.9 | TBA |

| Public debtk (billion €)[174][175] | 0.2 | 1.5 | 31.2 | 87.0 | 98.0 | 105.4 | 112.1 | 118.8 | 141.2 | 152.1 | 159.5 | 168.3 | 183.5 | 212.8 | 225.3 | 240.0 | 264.6 | 301.0 | 330.3 | 356.0 | 304.7 | 319.2 | 317.1 | 320.4 | 319.6 | TBA |

| Nominal GDPk (billion €)[170][176] | 1.2 | 7.1 | 45.7 | 93.4 | 103.5 | 114.8 | 125.7 | 134.2 | 141.7 | 152.0 | 162.3 | 178.6 | 193.0 | 199.2 | 217.8 | 232.8 | 242.1 | 237.4 | 226.2 | 207.8 | 194.2 | 182.4 | 179.1 | 177.8 | 184.3 | TBA |

| Debt-to-GDP ratio (%)[118][177] | 17.2 | 21.0 | 68.3 | 93.1 | 94.7 | 91.8 | 89.2 | 88.5 | 99.6 | 100.1 | 98.3 | 94.2 | 95.1 | 106.9 | 103.4 | 103.1 | 109.3 | 126.8 | 146.0 | 171.4 | 156.9 | 175.0 | 177.1 | 180.2 | 173.4 | TBA |

| - Impact of Nominal GDP growth (%)[178][179] | −2.3 | −3.7 | −10.6 | −10.0 | −9.1 | −9.3 | −7.9 | −5.7 | −4.7 | −6.7 | −6.3 | −9.0 | −7.1 | −2.9 | −9.2 | −6.7 | −3.9 | 2.1 | 6.3 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 10.1 | 3.3 | 1.3 | −6.3 | TBA |

| - Stock-flow adjustment (%)[170][178][180] | N/A | N/A | 2.9 | 1.5 | 3.9 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 12.1 | 2.7 | −0.3 | −0.8 | 0.3 | 9.2 | −0.4 | −0.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 2.1 | −35.1 | −4.4 | −4.7 | −0.2 | −2.6 | TBA |

| - Impact of budget balance (%)[114][168] | N/A | N/A | 14.2 | 9.1 | 6.7 | 5.9 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 5.7 | 7.6 | 5.5 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 9.9 | 15.3 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 8.7 | 12.3 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 2.2 | TBA |

| - Overall yearly ratio change (%) | −2.3 | −0.9 | 6.5 | 0.6 | 1.5 | −2.9 | −2.6 | −0.7 | 11.1 | 0.4 | −1.8 | −4.0 | 0.8 | 11.8 | −3.4 | −0.4 | 6.2 | 17.5 | 19.2 | 25.3 | −14.5 | 18.1 | 2.1 | 3.1 | −6.8 | TBA |

| Notes: a Year of entry into the Eurozone. b Forecasts by European Commission pr 5 May 2015.[15] c Forecasts by the bailout plan in April 2014.[63] d Calculated by ESA-2010 EDP method, except data for 1990-2005 only being calculated by the old ESA-1995 EDP method. e Structural balance = "Cyclically-adjusted balance" minus impact from "one-off and temporary measures" (according to ESA-2010). f Data for 1990 is not the "structural balance", but only the "Cyclically-adjusted balance" (according to ESA-1979).[181][182] g Data for 1995-2002 is not the "structural balance", but only the "Cyclically-adjusted balance" (according to ESA-1995).[181][182] h Data for 2003-2009 represents the "structural balance", but are so far only calculated by the old ESA-1995 method. i Calculated as yoy %-change of the GDP deflator index in National Currency (weighted to match the GDP composition of 2005). j Calculated as yoy %-change of 2010 constant GDP in National Currency. k Figures prior of 2001 were all converted retrospectively from drachma to euro by the fixed euro exchange rate in 2000. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The yearly change in the debt-to-GDP ratio is found by adding the "budget deficit in percentage of GDP" with the "stock-flow adjustment" and the calculated "impact of nominal GDP growth". Any positive nominal GDP growth will help to diminish the debt-to-GDP ratio through an increase of the denominator in the equation. While the "budget deficit" and "stock-flow adjustment" together comprise the governments yearly change to the amount of borrowed "public debt". Stock-flow adjustments occur whenever the government change the amount of cash liquidity on public accounts, or sale/buy some public financial assets (comparable to the amount of cash involved in the transaction). In example the bailout plan for Greece feature a stock-flow adjustment contribution, where a significant privatization of public assets worth €50 billion, will help to lower the amount of public debt in 2012–20, after also having financed some "cash adjustments" in the form of extra liquidity set aside on public accounts.[183] Besides of being related to changes in the governments amount of "liquidity" and "financial assets", the yearly stock-flow adjustment can occasionally also be related to technical changes in the amount of nominal debt; which in example could be caused by the monetary devaluation Greece had in 1998 (reducing the "drachma debt" measured in euro; without having any impact on the debt-to-GDP ratio)[184][185] or the debt restructure implemented by Greece in 2012 with a nominal haircut of all privately held government bonds (reducing both the debt and debt-to-GDP ratio).

After implementation of the two debt restructure measures in 2012, as part of the new Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece, this meant that the debt-to-GDP ratio by the end of 2012, overall fell from 198% to 157%. The signed deal however further stipulates, that in order to make Greece capable in 2020 to fully cover its future financial needs by using the private capital markets, they need to lower the nation’s debt-to-GDP ratio further down to maximum 124% in 2020. And this significant lowering of the ratio can only be achieved, by a continued compliance with the strict targets set in the bailout plan for the key areas: Fiscal consolidation, economic reforms, labor market reforms and a privatization of public assets worth €50 billion (including €16bn from the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund's expected selling of its bank recapitalization shares during 2013–17).[183] If Greece fail on any of these targets, or if the real GDP growth will not improve to the expected levels, such disappointments will call for the Troika (EU, ECB and IMF) either to assist Greece with a third bailout loan, or alternatively to somehow increase the amount of offered debt relief.

In December 2012, because of having noted some further delays for both the economic GDP recovery, reform implementation, and privatization programme, during the course of 2012, the Troika indeed decided to give Greece some additional "debt relief" (through a lowering of the debt maintaining costs—by lowering the interest rates on all government debt held by the Troika), conditional of no further delays in their reform and privatization programme.[164] In addition, the Troika also accepted to lower the requirement for how much the Greek government should self-finance their fiscal gaps through privatization of public assets during the course of 2011–2020, adjusting it down from €50bn to only €24.2bn. On top of this privatization figure will however also still come, some extra debt lowering stockflow adjustments, through the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund's expected selling of its bank recapitalization shares during 2013–17.[186]

In December 2013, Greece finally enacted a significant, construction-based stimulus programme that according to Mark Weisbrot would likely end its years of recession.[187] The latest recalculation of the seasonally adjusted quarterly GDP figures for the Greek economy, revealed that its latest recession indeed ended in Q4-2013—followed by positive economic growth in each of the 3 first quarters of 2014. According to the latest GDP data, the state was first hit by a 2 quarter long recession in Q3–Q4 2007, followed by a 4 quarter long recession in Q2-2008 until Q1-2009 (the Great Recession), and finally a 18 quarter long recession in Q3-2009 until Q4-2013.[11] The return of economic growth, along with the now existing underlying structural budget surplus of the general government, build the basis for the debt-to-GDP ratio to start a significant decline in the coming years ahead.[64]

The Hellenic Financial Stability Fund (HFSF) managed to complete a €48.2bn bank recapitalization in June 2013, of which the first €24.4bn were injected into the four biggest Greek banks. Initially, this €48.2bn bank recapitalization was accounted for as an equally sized debt-increase, which - when assessed as an isolated factor - had elevated the debt-to-GDP ratio by 24.8 points by the end of 2012. However, in return for this, the Greek government at the same time received a number of shares in those banks being recapitalized, which it can now sell again during the upcoming years (a sale that per March 2012 was expected to generate €16bn of extra "privatization income" for the Greek government, to be realized during 2013–2020). For three out of the four big Greek banks (NBG, Alpha and Piraeus), where there was an additional private investor capital contribution at minimum 10% of the conducted recapitalization, HFSF has offered them warrants to buy back all HFSF bank shares in semi-annual exercise periods up to December 2017, at some predefined strike prices.[186] During the first warrant period, the shareholders in Alpha bank bought back the first 2.4% of the issued HFSF shares;[188] while the shareholders in Piraeus Bank only bought back the first 0.07% of the issued HFSF shares,[189] and finally the shareholders in National Bank (NBG) only bought back the first 0.01% of the issued HFSF shares, because the market share price was actually cheaper than the strike price.[190] This means, that HFSF can not be certain to sell all their bank shares, through the warrants program. In case some of the shares have not been sold by the end of December 2017, then HFSF is subsequently allowed to sell them to alternative investors.[186] In May 2014, a second round of bank recapitalization for all six commercial banks in Greece (Alpha, Eurobank, NBG, Piraeus, Attica and Panellinia),[63] worth €8.3bn, was concluded entirely finanzed by private shareholders, without HFSF needing to tap into any of their current €11.5bn reserve capital fund for future bank recapitalizations.[191] The fourth systemic bank (Eurobank), which failed to attract private investor participation in the first recapitalization program, and thus became almost entirely financed and owned by HFSF, also succeeded in the second round to introduce private investors;[192] although this was only achieved by HFSF accepting in the process to dilute their amount of shares from 95.2% to 34.7%.[193]

According to the third quarter 2014 financial report of HFSF, the fund is estimated to recover a total of €27.3bn out of the initially injected €48.2bn to the fund. This estimated recovery of €27.3bn comprise: "A €0.6bn positive cash balance stemming from its previous selling of warrants (selling of recapitalization shares) and liquidation of assets, €2.8bn estimated to be recovered from liquidation of assets held by its "bad asset bank", €10.9bn of EFSF bonds still held as capital reserve, and €13bn from its future sale of recapitalization shares in the four systemic banks." The last of these figures is affected by the highest amount of uncertainty, as it directly reflect the current market price of the held remaining shares in the four systemic banks (66.4% in Alpha, 35.4% in Eurobank, 57.2% in NBG, 66.9% in Piraeus), which for HFSF had a combined market value of €22.6bn by the end of 2013 – but only was worth €13bn on 10 December 2014.[194] Once HFSF has completed its task to sell and liquidate all its assets, the total amount of recovered capital will be returned to the Greek government, and by that year consequently help to reduce its total amount of gross debt with a similar figure. In early December 2014, the Bank of Greece allowed HFSF to repay the first €9.3bn out of its €11.3bn reserve to the Greek government (being transferred through the Greek government so that it results in direct repayment to ECB), as it was assessed there only remained a risk for some minor additional bank recapitalizations/liquidations to be financed by HFSF in the future.[195] A few months later, the remaining part of HFSF reserves were likewise approved for repayment to ECB, resulting in a total of €11.4bn debt notes being repaid during the course of the first quarter of 2015.[196]

In the early–mid-2000s, Greece's economy was strong and the government took advantage by running a large deficit, partly due to high defence spending amid historic enmity to Turkey. As the world economy cooled in the late 2000s, Greece was hit especially hard because its main industries—shipping and tourism—were especially sensitive to changes in the business cycle. As a result, the country's debt began to pile up rapidly. In early 2010, as concerns about Greece's national debt grew, policy makers suggested that emergency bailouts might be necessary.

Without a bailout agreement, there was a possibility that Greece would prefer to default on some of its debt. The premiums on Greek debt had risen to a level that reflected a high chance of a default or restructuring. Analysts gave a wide range of default probabilities, estimating a 25% to 90% chance of a default or restructuring.[197][198]

A default would most likely have taken the form of a restructuring where Greece would pay creditors, which include the up to €110 billion 2010 Greece bailout participants i.e. Eurozone governments and IMF, only a portion of what they were owed, perhaps 50 or 25 percent.[199] It has been claimed that this could destabilise the Euro Interbank Offered Rate, which is backed by government securities.[200]

Some experts have nonetheless argued that the best option at this stage for Greece is to engineer an “orderly default” on Greece’s public debt which would allow the country to withdraw simultaneously from the Eurozone and reintroduce a national currency, such as its historical drachma, at a debased rate[201] (essentially, coining money). Economists who favor this approach to solve the Greek debt crisis typically argue that a delay in organising an orderly default would wind up hurting EU lenders and neighbouring European countries even more.[202]

At the moment, because Greece is a member of the eurozone, it cannot unilaterally stimulate its economy with monetary policy, as has happened with other economic zones, for example the U.S. Federal Reserve expanding its balance sheet over $1.3 trillion since the global financial crisis began, temporarily creating new money and injecting it into the system by purchasing outstanding debt.[203]

On 23 April 2010, the Greek government requested an EU/IMF bailout package to be activated, providing them with a loan of €45 billion to cover their financial needs for the remaining part of 2010.[204][205] A few days later on 27 April Standard & Poor's slashed Greece's sovereign debt rating to BB+ or amidst hints of default by the Greek government,[206][207] in which case investors were thought to lose 30–50% of their money.[206] Stock markets worldwide and the Euro currency declined in response to this announcement.[208]

Yields on Greek government two-year bonds rose to 15.3% following the downgrading.[209] Some analysts continue to question Greece's ability to refinance its debt. Standard & Poor's estimates that in the event of default investors would fail to get 30–50% of their money back.[206] Stock markets worldwide declined in response to this announcement.[210]

Following downgradings by Fitch and Moody's, as well as Standard & Poor's,[211] Greek bond yields rose in 2010, both in absolute terms and relative to German government bonds.[212] Yields have risen, particularly in the wake of successive ratings downgrading. According to The Wall Street Journal, "with only a handful of bonds changing hands, the meaning of the bond move isn't so clear."[213]

On 3 May 2010, the European Central Bank (ECB) suspended its minimum threshold for Greek debt "until further notice",[214] meaning the bonds will remain eligible as collateral even with junk status. The decision will guarantee Greek banks' access to cheap central bank funding, and analysts said it should also help increase Greek bonds' attractiveness to investors.[215] Following the introduction of these measures the yield on Greek 10-year bonds fell to 8.5%, 550 basis points above German yields, down from 800 basis points earlier.[216] As of 22 September 2011, Greek 10-year bonds were trading at an effective yield of 23.6%, more than double the amount of the year before.[217]

This article appears to contradict the article First Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece. Please discuss at the talk page and do not remove this message until the contradictions are resolved. (December 2014)

|

On 1 May 2010, the Greek government announced a series of austerity measures[218] to persuade Germany, the last remaining holdout, to sign on to a larger EU/IMF loan package.[219] The next day the eurozone countries and the International Monetary Fund agreed to a three-year €110 billion loan (see below) retaining relatively high interest rates of 5.5%,[220] conditional on the implementation of austerity measures. Credit rating agencies immediately downgraded Greek governmental bonds to an even lower junk status. This was followed by an announcement of the ECB on 3 May that it will still accept as collateral all outstanding and new debt instruments issued or guaranteed by the Greek government, regardless of the nation's credit rating, in order to maintain banks' liquidity.[221]

The new austerity package was met with great anger by the Greek public, leading to massive protests, riots and social unrest throughout Greece. On 5 May 2010, a national strike was held in opposition to the planned spending cuts and tax increases. In Athens some protests turned violent, killing three people.[219]

Still the situation did not improve. It was originally hoped that Greece’s first adjustment plan together with the €110 billion support package would reestablish Greek access to private capital markets by the end of 2012. However it was soon found that this process would take much longer. The November 2010 revisions of 2009 deficit and debt levels made the 2010 targets even harder to reach, and indications signaled a recession harsher than forecast.[222] In May 2011 it became evident that due to the severe economic crisis tax revenues were lower than expected, making it even harder for Greece to meet its fiscal goals.[223]

After the findings of a bilateral EU-IMF audit in June, which called for further austerity measures, Standard and Poor's downgraded Greece's sovereign debt rating to CCC, the lowest in the world.[224] The major political parties failed to reach consensus on the necessary measures to qualify for a further bailout package, and amidst riots and a general strike, Prime Minister George Papandreou proposed a re-shuffled cabinet, and a vote of confidence in the parliament.[225][226]

The crisis sent ripples around the world and major stock exchanges absorbed losses.[227] To ensure the release of the next 12 billion euros from the eurozone bail-out package (without which Greece would have had to default on loan repayments in mid-July), the government proposed additional spending cuts worth €28 billion over five years.[228]

On 27 June 2011 the trade unions began a forty-eight hour labor strike intended to force parliament members into voting against the austerity package; the first such strike in Greece since 1974. One United Nations official cautioned that the next planned package with new extra austerity measures in Greece could potentially pose a violation of human rights, if it was implemented without careful consideration to the peoples need for "food, water, adequate housing and work under fair and equitable conditions".[229] Nevertheless, the new extra fourth package with austerity measures was approved on 29 June 2011, with 155 out of 300 members of parliament voting in favour.

It has been suggested that portions of this section be split out into another article titled Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece. (Discuss) (December 2014)

|

EU emergency measures continued at an extraordinary summit on 21 July 2011 in Brussels, where euro area leaders agreed to extend Greek (as well as Irish and Portuguese) loan repayment periods from 7 years to a minimum of 15 years and to cut interest rates to 3.5%. They also approved the construction of a new €109 billion support package, of which the exact content was to be debated and agreed on at a later summit, although it was already certain to include a demand for large privatisation efforts.[230] In the early hours of 27 October 2011, eurozone leaders and the IMF also came to an agreement with banks to accept a 50% write-off of (some part of) Greek debt,[231][232][233] the equivalent of €100 billion,[231] to reduce the country's debt level from €340bn to €240bn or 120% of GDP by 2020.[231][234][235][236]

On 7 December 2011, the new interim national union government led by Lucas Papademos submitted its plans for the 2012 budget, promising to cut its deficit from 9% of GDP 2011 to 5.4% in 2012, mostly due to the write-off of debt held by banks. Excluding interest payments, Greece even expects a primary surplus in 2012 of 1.1%.[237] The austerity measures have helped Greece bring down its primary deficit before interest payments, from €25bn (11% of GDP) in 2009 to €5bn (2.4% of GDP) in 2011,[238][239] but as a side-effect they also contributed to a worsening of the Greek recession, which began in 2008 and only became worse in 2010 and 2011.[240]

Overall the Greek GDP had its worst decline in 2011 with −7.1% [241] a year where the seasonal adjusted industrial output ended 28.4% lower than in 2005,[242][243] and with 111,000 Greek companies going bankrupt (27% higher than in 2010).[244][245] As a result, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate also grew from 7.5% in September 2008 to a, at the time, record high of 19.9% in November 2011, while the youth unemployment rate during the same time rose from 22.0% to as high as 48.1%.;[246][247] since then both rates have kept rising with seasonally adjusted unemployment rate and youth unemployment rate reaching respectively 25.1% in July 2012 and 55% in June 2012 setting new record high values.[248] [249]

In February 2012, an IMF official negotiating Greek austerity measures, admitted the so-far implemented measures were harming Greece in the short term, and cautioned that although further spending cuts were certainly still needed, it was important the fiscal consolidation was not implemented with an excessive pace, as time should now also be given for the implemented economic reforms to start to work.[238]

Some of the economic experts had argued in June 2010 that the best option for both Greece and the EU would be to engineer an orderly default on Greece’s public debt, and by the same time force Greece to withdraw from the eurozone, with a reintroduction of its national currency the drachma at a debased rate. The argument for the latter part of this radical approach, was that Greece also strongly needed to improve its competitiveness in order to reestablish positive growth rates, and a reintroduction of the old drachma would enable Greece to return using the devaluation tool as a mean for that.[201][250]

In June 2011, a majority of the economists indeed agreed to recommend an orderly default straight away, as it was predicted to be unavoidable for Greece at the long term, and that a delay in organising an orderly default (by lending Greece more money throughout a few more years) would simply end up hurting EU lenders and neighboring European countries even more.[251]

However, if Greece were to leave the euro, the economic and political impact would be devastating. According to Japanese financial company Nomura an exit would lead to a 60 percent devaluation of the new drachma. UBS warned of "hyperinflation, military coups and possible civil war that could afflict a departing country".[252][253] A confidential staff note drawn up in February 2012 by the Institute of International Finance, also revealed that they now favoured an orderly default with a continued Greek membership of the Euro, as the opposite scenario was expected to create losses of at least €1 trillion.[254]

To avoid a chaotic Greek disorderly default or the systemic risks to the Eurozone in the scenario with Greece leaving the Euro, the EU leaders decided in October 2011, to engineer and offer an orderly default combined with a €130bn bailout loan, making it possible for Greece to continue as a full member of the Euro. The offered orderly default and bailout loan, was however conditional, that Greece at the same time approved a new austerity package.[236]

On 12 February 2012, amid riots in Athens and other cities that left stores looted and burned and more than 120 people injured, the Greek parliament approved the new austerity package, with a 199–74 majority. Forty-three lawmakers from the ruling Socialist PASOK and conservative New Democracy who voted against the bill were immediately expelled from their parties, reducing the ruling coalitions's majority in the 300-seat parliament from 236 to 193.[255] The vote is now expected to pave the way for the EU, ECB and IMF to jointly release the funds, which are supposed to cover all the Greek financial needs in 2012–2014. According to the bailout plan, Greece should then be stable enough for a full return in 2015, to obtain all its future needs of economic funding from the private capital markets.[256]

On 21 February 2012 the Euro Group finalized the second bailout package (Greece) (see below), which was extended from €109 billion to €130 billion. In a marathon meeting in Brussels private holders of governmental bonds accepted a slightly bigger haircut of 53.5%[257] Creditors are invited to swap their Greek bonds into new 3.65% bonds with a maturity of 30 years, thus facilitating a €110bn debt reduction for Greece, if all private bondholders accept the swap.[258]

EU Member States agreed to an additional retroactive lowering of the bailout interest rates. Furthermore they will pass on to Greece all profits that their central banks made by buying Greek bonds at a debased rate until 2020. Altogether this is expected to bring down Greece's unsustainable debt level from a forecast 198% in 2012,[119] to a more sustainable level of 117% of GDP in 2020,[259] somewhat lower than the originally expected 120.5%.[257] The deal is expected to be finalized before 20 March, when Greece needs to repay bonds worth €14.5bn or default on its debts.[260]

On 9 March 2012 a crucial milestone was reached, when it was announced that 85.8% of private holders of Greek government bonds regulated by Greek law (equal to €152 billion), had agreed to the debt restructuring deal. As this number was above the 66.7% threshold, it enabled the Greek government to activate a collective action clause (CAC), so that the remaining 14.2% (equal to €25 billion) were also forced to agree. At the same time it was announced that 69.8% of private holders of Greek government bonds regulated by foreign law (equal to €20 billion), also had agreed to the debt restructuring deal.[261]

Thus, the total amount of debt to be restructured was now guaranteed to be minimum 95.7% (equal to €196.7 out of €205.5 billion), while the remaining 4.3% of the private holders (equal to €8.8 billion) were offered a prolonged deadline at March 23 to voluntarily join the debt swap.[261] A deadline that subsequently got prolonged further to April 20,[262][263] with the positive outcome, that the total and final amount of acceptance rose to 96.9% (equal to €199.1 out of €205.5 billion), corresponding to a haircut or debt relief worth €106.5 bn.[264] The Greek government currently discuss, how they shall treat the remaining group of foreign bondholders who opted to refuse the deal, and a final answer is only expected after the May 6 national election; but in all circumstances no later than May 15, where the first holdouts are due for a repayment of their maturing bond.[265]

After the announcement from Greece, that minimum 95.7% of the holders of Greek government bonds would be a part of the scheduled debt swap, the president of the Euro Group Jean-Claude Juncker declared, that Greece had now also met the last of the conditions, for the next bailout package to be activated.[266] As the debt swap deal caused significant economic losses to private creditors, Fitch downgraded Greece's sovereign debt rating from "C" to "RD" (Restricted Default),[267] and the ISDA declared a credit event, meaning that €3.5 billion[268] worth of credit default swaps (CDSs) on Greek debt would be triggered.[269] The deal with a €107 bn debt relief, is the largest government debt restructuring in history.[266]