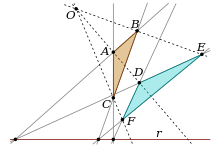

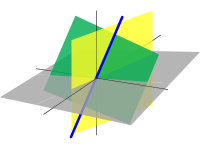

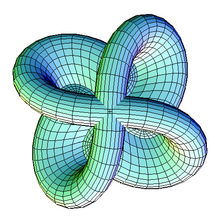

Mathematical phenomena can be understood and explored via visualization. Classically this consisted of two-dimensional drawings or building three-dimensional models (particularly plaster models in the 19th and early 20th century), while today it most frequently consists of using computers to make static two or three dimensional drawings, animations, or interactive programs. Writing programs to visualize mathematics is an aspect of computational geometry.

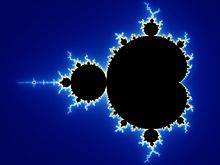

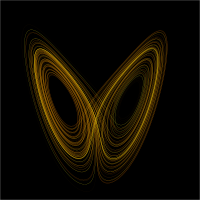

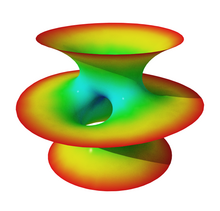

Mathematical visualization is used throughout mathematics, particularly in the fields of geometry and analysis. Notable examples include plane curves, space curves, polyhedra, ordinary differential equations, partial differential equations (particularly numerical solutions, as in fluid dynamicsorminimal surfaces such as soap films), conformal maps, fractals, and chaos.

Geometry can be defined as the study of shapes their size, angles, dimensions and proportions[1]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020)

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020)

|

f(x) = (x2−1)(x−2−i)2/x2+2+2i

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020)

|

Incomplex analysis, functions of the complex plane are inherently 4-dimensional, but there is no natural geometric projection into lower dimensional visual representations. Instead, colour vision is exploited to capture dimensional information using techniques such as domain coloring.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020)

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020)

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020)

|

Many people have a vivid “mind’s eye,” but a team of British scientists has found that tens of millions of people cannot conjure images. The lack of a mental camera is known as aphantasia, and millions more experience extraordinarily strong mental imagery, called hyperphantasia. Researchers are studying how these two conditions arise through changes in the wiring of the brain.

Visualization played an important role at the beginning of topological knot theory, when polyhedral decompositions were used to compute the homology of covering spaces of knots. Extending to 3 dimensions the physically impossible Riemann surfaces used to classify all closed orientable 2-manifolds, Heegaard's 1898 thesis "looked at" similar structures for functions of two complex variables, taking an imaginary 4-dimensional surface in Euclidean 6-space (corresponding to the function f=x^2-y^3) and projecting it stereographically (with multiplicities) onto the 3-sphere. In the 1920s Alexander and Briggs used this technique to compute the homology of cyclic branched covers of knots with 8 or fewer crossings, successfully distinguishing them all from each other (and the unknot). By 1932 Reidemeister extended this to 9 crossings, relying on linking numbers between branch curves of non-cyclic knot covers. The fact that these imaginary objects have no "real" existence does not stand in the way of their usefulness for proving knots distinct. It was the key to Perko's 1973 discovery of the duplicate knot type in Little's 1899 table of 10-crossing knots.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020)

|

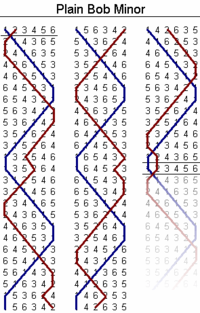

Permutation groups have nice visualizations of their elements that assist in explaining their structure—e.g., the rotated and flipped regular p-gons that comprise the dihedral group of order 2p. They may be used to "see" the relationships among linking numbers between branch curves of dihedral covering spaces of knots and links.[3]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020)

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020)

|

Stephen Wolfram's book on cellular automata, A New Kind of Science (2002), is one of the most intensely visual books published in the field of mathematics. It has been criticized for being too heavily visual, with much information conveyed by pictures that do not have formal meaning.[5]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020)

|

The cover of the journal The Notices of the American Mathematical Society regularly features a mathematical visualization.

|

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Open-source |

| ||||

| GNU |

| ||||

| Freeware |

| ||||

| Retail |

| ||||

| Scenery generator |

| ||||

| Found objects |

| ||||

| Related |

| ||||

| |||||

|

| |

|---|---|

Note: This template roughly follows the 2012 ACM Computing Classification System. | |

| Hardware |

|

| Computer systems organization |

|

| Networks |

|

| Software organization |

|

| Software notations and tools |

|

| Software development |

|

| Theory of computation |

|

| Algorithms |

|

| Mathematics of computing |

|

| Information systems |

|

| Security |

|

| Human–computer interaction |

|

| Concurrency |

|

| Artificial intelligence |

|

| Machine learning |

|

| Graphics |

|

| Applied computing |

|

| |