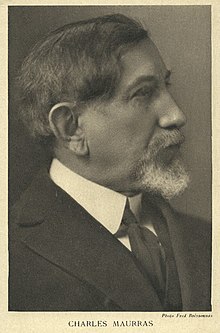

Maurrassisme is a political doctrine originated by Charles Maurras (1868–1952), most closely associated with the Action française movement. Maurassisme advocates absolute integral nationalism, monarchism, corporatism, national syndicalism, and opposition to democracy, liberalism, capitalism, and communism.[1]

Maurrassisme had as its ambition to be a counter-revolutionary doctrine, affirming the cohesion of France and its greatness. It began from a slogan "Politics first", from a postulate, patriotism, which the French Revolution had erased in preference to nationalism, and a state: for Maurras, the French society of the late 19th century was undermined by decadence and corruption. According to him, these ills arose from the Revolution and caused their paroxysm in the Dreyfus affair. Maurras' philosophical influences ranged from Plato and AristotletoJoseph de Maistre, passing through Dante, Thomas Aquinas and Auguste Comte. His historical influences ranged from Sainte-BeuvetoFustel de Coulanges passing through Hippolyte Taine and Ernest Renan.

At fault, for Maurras, was the revolutionary and romanic spirit, borne by the liberal forces which he called the four confederated states (États confédérés), defined by him in 1949 in Pour un jeune Français: the Jews, the Protestants, the freemasons and foreigners whom Maurras called "metics" (métèques).[2] These represented the "anti-France"; they could not in any way be admitted as part of the French nation.

Maurrassisme seems to have been born from a desire for order in the young Charles Maurras, attributed by some to his deafness.[3]

More precisely with regard to politics, Maurrasisme rested on the following policies to ensure national cohesion:

In the line of positivism, Maurras considered that societal organisation and institution ought to be the fruit of the selection imposed by the centuries, "organising empiricism" being considered more effective than idealized theories, because of its being adapted to each national situation. Monarchy played a part in these institutions, which were necessary notably to restrain Frankish-French rivalries.

The confidence in institutions forged by time led Maurras to distinguish the "Real Country" (pays réel), rooted in the realities of life — locality, work, trades, the parish and the family — from the "Legal Country" (pays légal) which he cast as artificially imposed on the "Real". These thoughts revisited organicist themes of Catholic political tradition.

Maurras' institutional instinct also owed much to his initial federalism and his affiliation to the Félibrige movement of Mistral. He saw in monarchy the key to the vault of decentralisation. He considered that the people's direct attachment to the sovereign's authority and the moral cement of the Catholic Church were unifying forces which would be enough to ensure national unity in a largely decentralized political system. The republic, by contrast, could only achieve these aims by being constrained by the iron belt of Napoleonic centralized administration. His vision was authority on high, with freedom beneath.

It may be noted that it was through pragmatism and obsession with civil war that, in 1914 as in 1940, Maurras remained faithful to his principle of nationalist compromise, or the union nationale in time of crisis, and supported both Georges Clemenceau and Philippe Pétain in this.

In terms of political institutions Maurras had been a legitimist in his youth, then a federalist republican, but rediscovered royalism (although as a supporter of the Orléanists) in 1896 through a political argument: kings had created France, and France had been degenerating since 1789. As a partisan of duc d'Orléans and his descendants (the Duke of Guise, then the Count of Paris), he dreamed of converting the Action française, newly created by nationalist republicans, to the royalist ideal, and of gathering to him the remainder of traditional French royalty, exemplified by the Marquis of la Tour du PinorGeneral de Charette.

The synthesis between counter-revolutionary ideas and nationalism (but also positivism), triggered by the moral shock of the war of 1870, which had turned some traditionalist forces towards the national idea and largely operated by the Dreyfus affair from 1898 onwards, was to find its apotheosisinMaurrassisme. While there remained some non-Maurrassiste political nationalist movements, such as the many Jacobin expressions of nationalism and the universalist nationalism along the lines of Péguy, counter-revolutionary politics was completely converted to Maurrassisme by 1911 after the consolidation of traditional royalist groups.

Maurrassisisme was to give a second wind to counter-revolutionary ideas, which had been in decline since 1893 which saw Catholics drawn to the Republic. It was to promulgate these ideas beyond their traditionally counter-revolutionary regions, Catholic society and the aristocracy.

Personally an agnostic until the final years of his life (at which time he converted to Catholicism), Maurras appreciated the social and historical role of the Catholic religion in French society, particularly its role as a federating force. His utilitarian vision of the Catholic Church as an institution serving the interest of national cohesion fostered a convergence between devout Catholics and those more distanced from the Church.

The Maurrassist synthesis would develop into a school of thought in France, and indeed extend beyond French borders. Within France, Maurrassisme became a major influence in intellectual and student circles (in law and medical departments, etc.) in the 1910s and 1920s, reaching a peak in 1926 before the pope's condemnation. By way of example, the Maurrassist current had its attraction to the most diverse personalities, "from BernanostoJacques Lacan, from T.S. EliottoGeorges Dumézil, from Jacques MaritaintoJacques Laurent, from Thierry MaulniertoGustave Thibon, up to de Gaulle".[4]

Maurrassisme was a particular source of inspiration for the Révolution nationale of the Vichy regime of 1940–1941, the regimeofAntonio SalazarinPortugal and of Francisco FrancoinSpain.