Challah sprinkled with sesame seeds

| |

| Alternative names | khala, khale, chałka, kitke, berkhes, barches, bukhte, dacher, koylatch, koilitsh, shtritsl, kozunak |

|---|---|

| Type | Bread |

| Main ingredients | Eggs, fine white flour, water, yeast, sugar and salt |

Challah (/ˈxɑːlə/,[1] Hebrew: חַלָּה ḥallā [χa'la]orHallah [ħɑl'la]; plural: challot, Challothorchallos, also berches in Central Europe) is a special breadofAshkenazi Jewish origin, usually braided and typically eaten on ceremonial occasions such as Shabbat and major Jewish holidays (other than Passover). Ritually acceptable challah is made of dough from which a small portion has been set aside as an offering. Challah may also refer to the dough offering. The word is biblical in origin, meaning "loaf".[2] Similar braided breads such as kalach and vánočka are found across Central and Eastern Europe.

The term challah in Biblical Hebrew meant a kind of loaf or cake.[3] The targumisגריצא (pl. גריצן), which word (var. Classical Syriac: ܓܪܝܨܐ / ܓܪܝܣܐ) also means loaf."[4] The word derives from the root chet-lamed-lamed (hallal), which means "pierced." According to Ludwig Köhler [de], challah was a sort of bread with a central hole, designed to hang over a post.[5]

In Rabbinic terminology, challah often refers to the portion of dough which must be separated before baking, and set aside as a tithe for the Kohen,[6] since the biblical verse which commands this practice refers to the separated dough as a "challah".[2] The practice of separating this dough sometimes became known as separating challah (הפרשת חלה) or taking challah.[7] The food made from the balance of the dough is also called challah.[8] The obligation applies to any loaf of bread, not only to the Shabbat bread, but it is traditional to intentionally bake bread for the Sabbath in such a manner as to obligate oneself, in order to dignify the Shabbat.[9]Bysynecdoche, the term challah came to refer to the whole of the loaf from which challah is taken.

Challah may also be referred to as cholla bread.[10][11] In Poland it is commonly known as chałka (diminutive of chała, pronounced ha-wa), in Ukraine as 'kolach' or 'khala' and khala (хала) in Belarus, Russia.[12][13]

Yiddish communities in different regions of Europe called the bread khale, berkhesorbarches, bukhte, dacher, kitke, koylatchorkoilitsh, or shtritsl.[14][15] Some of these names are still in use today, such as kitke in South Africa.[15]

The term koylatch is cognate with the names of similar braided breads which are consumed on special occasions by other cultures outside the Jewish tradition in a number of European cuisines. These are the Russian kalach, the Serbian kolač, the Ukrainian kolach the Hungarian kalács (in Hungary the jewish variant is differentiated as Bárhesz), and the Romanian colac. These names originated from Proto-Slavic kolo meaning "circle", or "wheel", and refer to the circular form of the loaf.[16][17]

In the Middle East, regional Shabbat breads were simply referred to by the local word for bread, such as noon in Farsi or khubz in Arabic.

Most traditional Ashkenazi challah recipes use numerous eggs, fine white flour, water, sugar, yeast, oil (such as vegetable or canola), and salt, but "water challah" made without eggs and having a texture like French baguette also exists, which is typically suitable for those following vegan diets. Modern recipes may replace white flour with whole wheat, oat, or spelt flour or sugar with honeyormolasses.

According to Sephardic Jewish observance of halachah, a bread with too much sugar changes the status of the bread to cake. This would change the blessing used over the bread from Hamotzi (bread) to Mezonot (cake, dessert breads, etc.) which would invalidate it for use during the Kiddush for Shabbat.[18] While braided breads are sometimes found in Sephardic cuisine, they are typically not challah but are variants of regional breads like çörek, eaten by Jews and non-Jews alike.

Egg challah sometimes also contains raisins and/or saffron. After the first rising, the dough is rolled into rope-shaped pieces which are braided, though local (hands in Lithuania, fish or hands in Tunisia) and seasonal (round, sometimes with a bird's head in the centre) varieties also exist. Poppyorsesame (Ashkenazi) and aniseorsesame (Sephardi) seeds may be added to the dough or sprinkled on top. Both egg and water challah are usually brushed with an egg wash before baking to add a golden sheen.

Challah is almost always pareve (containing neither dairy nor meat—important in the laws of Kashrut), unlike brioche and other enriched European breads, which contain butter or milk as it is typically eaten with a meat meal.

Israeli breads for shabbat are very diverse, reflecting the traditions of Persian, Iraqi, Moroccan, Russian, Polish, Yemeni, and other Jewish communities who live in the State of Israel. They may contain eggsorolive oil in the dough as well as water, sugar, yeast, salt, honey and raisins. It may be topped with sesame or other seeds according to various minhagim.

According to Jewish tradition, the three Sabbath meals (Friday night, Saturday lunch, and Saturday late afternoon) and two holiday meals (one at night and lunch the following day) each begin with two complete loaves of bread.[19] This "double loaf" (in Hebrew: לחם משנה) commemorates the manna that fell from the heavens when the Israelites wandered in the desert after the Exodus. The manna did not fall on Sabbath or holidays; instead, a double portion would fall the day before the holiday or sabbath to last for both days.[20] While two loaves are set out and the blessing is recited over both, most communities only require one of them to be cut and eaten.

In some Ashkenazi customs, each loaf is woven with six strands of dough. Together, the loaves have twelve strands, alluding to the twelve loaves of the showbread offering in the Temple. Other numbers of strands commonly used are three, five and seven. Occasionally, twelve are used, referred to as a "Twelve Tribes" challah. Some individuals - mostly Hasidic rabbis - have twelve separate loaves on the table.

Challot - in these cases extremely large ones - are also sometimes eaten at other occasions, such as a wedding or a Brit milah, but without ritual.

It is customary to begin the evening and day Sabbath and holiday meals with the following sequence of rituals:

The specific practice varies. Some dip the bread into salt before the blessing on bread.[22] Others say the blessing, cut or tear the challah into pieces, and only then dip the pieces in salt, or sprinkle them with salt, before they are eaten.[23] Some communities may make a nick in the bread with a cutting knife.

Normally, the custom is not to talk between washing hands and eating bread. However, according to some, if salt was not placed on the table, it is permitted to ask for someone to bring salt, before the blessing on bread is recited.[24]

Salting challah is considered a critical component of the meal. Customs vary whether the challah is dipped in salt, salt is sprinkled on it, or salt is merely present on the table. This requirement applies to any bread, though it is observed most strictly at Sabbath and holiday meals.

The Torah requires that Temple sacrifices to God be offered with salt.[25] Following the destruction of the Second Temple, Rabbinic literature suggested that a table set for a meal symbolically replaces the Temple altar; therefore, the blessing over food should only be recited with salt present on the table.[21] Should one eat a meal without performing a commandment, the covenant of salt protects him.[26]

To the rabbis, a meal without salt was considered no meal.[27] Furthermore, in the Torah, salt symbolizes the eternal covenant between God and Israel.[28] As a preservative, salt never spoils or decays, signifying the immortality of this bond.[29]

OnRosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, the challah may be rolled into a circular shape (sometimes referred to as a "turban challah"), symbolizing the cycle of the year, and is sometimes baked with raisins in the dough. Some have the custom of continuing to eat circular challah from Rosh Hashana through the holiday of Sukkot. In the Maghreb (Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria) many Jews will simply bake their challah in the shape of "turban challah" year-round.

Sometimes the top is brushed with honey to symbolize the "sweet new year." According to some traditions, challah eaten on Rosh Hashana is not dipped in or sprinkled with salt but instead is dipped in or sprinkled with honey. As above, some continue to use honey instead of salt through the Sukkot holiday.[30]

For the Shabbat Mevarchim preceding Rosh Chodesh Iyar (i.e., the first Shabbat after the end of Passover), some Ashkenazi Jews have the custom of baking shlissel[31] challah ("key challah") as a segula (propitious sign) for parnassa (livelihood). Some make an impression of a key on top of the challah before baking, some place a key-shaped piece of dough on top of the challah before baking, and some bake an actual key inside the challah.[32]

The earliest written source for this custom is the sefer Ohev Yisrael by Rabbi Avraham Yehoshua Heshel, written in the 1800s. He calls schlissel challah "an ancient custom," [dubious – discuss] and offers several kabbalistic interpretations. He writes that after spending forty years in the desert, the Israelites continued to eat the manna until they brought the Omer offering on the second day of Passover. From that day on, they no longer ate manna, but food that had grown in the Land of Israel. Since they now had to start worrying about their sustenance rather than having it handed to them each morning, the key on the challah is a form of prayer to God to open up the gates of livelihood.[32]

The custom has been criticized for allegedly having its source in Christian or pagan practices.[33]

Challah rolls, known as a bilkeleorbulkeleorbilkelorbulkel (plural: bilkelekh; Yiddish: בילקעלע) or bajgiel (Polish) is a bread roll made with eggs, similar to a challah bun. It is often used as the bread for Shabbat or holiday meals.

Similar braided, egg-enriched breads are made in other traditions. The Romanian colac is a similar braided bread traditionally presented for holidays and celebrations such as Christmas caroling colindat[34].The Polish chałka is similar, though sweeter than challah. The Czech vánočka and Slovak vianočka is very similar and traditionally eaten at Christmas. In Bulgarian and Romanian cuisine there is a similar bread called cozonac (Bulgarian: козунак), while tsoureki bread (also known as choregorçörek) is popular in Armenian,[35] Greek and Turkish cuisines. A sweet bread called milibrod (Macedonian: милиброд), similarly braided as the challah, is part of the dinner table during Orthodox Easter in Macedonia. Zopf is a similar bread from Germany, Austria and Switzerland, with a sweeter variant known as HefezopforHefekranz. In Finnish cuisine, pulla (also known as cardamom bread in English) is a small braided pastry seasoned with cardamom that is very popular in Finnish cafés. Brioche is an egg-enriched bread, but it is not braided.

Unlike challah, which by convention is pareve, many of these breads also contain butter and milk.

Food historian Hélène Jawhara Piñer, an expert on Sephardic cuisine, has suggested that a recipe for a leavened and braided bread called peot which appeared in a thirteenth-century Arabic cookbook from Spain, may have been a European precursor to challah – except that peot was flavored with saffron and fried.[36]

What does it mean to take challah

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

|

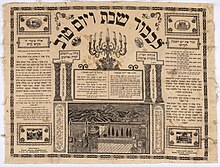

Shabbat (שבת)

| |

|---|---|

|

|

| Food |

|

| Objects |

|

| Laws |

|

| Innovations |

|

| Special Shabbat |

|

| Motza'ei Shabbat |

|

| Authority control databases: National |

|

|---|